Axis I and II Psychiatric Disorders After Traumatic Brain Injury: A 30-Year Follow-Up Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Patients who had suffered traumatic brain injury were evaluated to determine the occurrence of psychiatric disorders during a 30-year follow-up. METHOD: Sixty patients were assessed on average 30 years after traumatic brain injury. DSM-IV axis I disorders were diagnosed on a clinical basis with the aid of the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (version 2.1), and axis II disorders were diagnosed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders. Cognitive impairment was measured with a neuropsychological test battery and the Mini-Mental State Examination. RESULTS: Of the 60 patients, 29 (48.3%) had had an axis I disorder that began after traumatic brain injury, and 37 (61.7%) had had an axis I disorder during their lifetimes. The most common novel disorders after traumatic brain injury were major depression (26.7%), alcohol abuse or dependence (11.7%), panic disorder (8.3%), specific phobia (8.3%), and psychotic disorders (6.7%). Fourteen patients (23.3%) had at least one personality disorder. The most prevalent individual disorders were avoidant (15.0%), paranoid (8.3%), and schizoid (6.7%) personality disorders. Nine patients (15.0%) had DSM-III-R organic personality syndrome. CONCLUSIONS: The results suggest that traumatic brain injury may cause decades-lasting vulnerability to psychiatric illness in some individuals. Traumatic brain injury seems to make patients particularly susceptible to depressive episodes, delusional disorder, and personality disturbances. The high rate of psychiatric disorders found in this study emphasizes the importance of psychiatric follow-up after traumatic brain injury.

Psychiatric disorders are a major cause of disability after traumatic brain injury (1). Before the introduction of DSM-III in 1980, the most extensive study on psychiatric disorders after traumatic brain injury was reported in 1969 by Achte et al. (2), who examined 3,552 veterans for psychoses with a follow-up of 22–26 years. Since the introduction of DSM-III, adult patients with traumatic brain injury have been evaluated by means of structured psychiatric interviews and diagnostic criteria (1, 3–11). In these studies, the longest follow-up we know of has been 8 years (9, 11).

Major depression has been the most studied psychiatric disorder after traumatic brain injury. The rates of axis I disorders in patients with traumatic brain injury are 14%–77% for major depression (1, 3–5, 8–10), 2%–14% for dysthymia (1, 4, 5, 9), 2%–17% for bipolar disorder (3, 7–9), 3%–28% for generalized anxiety disorder (1, 6, 8–10), 4%–17% for panic disorder (1, 8–10), 1%–10% for phobic disorders (8–10), 2%–15% for obsessive-compulsive disorder (8–10), 3%–27% for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (9, 10, 12), 5%–28% for substance abuse or dependence (1, 8–10), and 1% for schizophrenia (3, 10).

Since the famous case of Phineas Gage in 1848 (13), personality change has been reported in 49% to 80% of patients with traumatic brain injury (14–16). Franulic et al. (17) found ICD-10 organic personality disorder in 32% of patients after traumatic brain injury. To our knowledge, there have been only two studies that used structured interviews and diagnostic criteria to examine the occurrence of all personality disorders after traumatic brain injury. Van Reekum et al. (8) found DSM-III-R personality disorders in seven (39%) of 18 patients. Hibbard et al. (11) investigated 100 individuals for DSM-IV personality disorders an average of 8 years after traumatic brain injury. Sixty-six percent of the patients had at least one personality disorder, and the most common were borderline (34%), obsessive-compulsive (27%), paranoid (26%), avoidant (26%), and antisocial (21%).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the occurrence of axis I and II disorders after traumatic brain injury. The average follow-up of the patients was 30 years, which is, to our knowledge, the longest ever reported.

Method

This study was a retrospective follow-up. The subjects were recruited from a group of 210 patients who had received traumatic brain injuries between 1950 and 1971 and who had been referred for neuropsychological evaluation to one of us (R.P.) at Turku University Central Hospital (Turku, Finland) between 1966 and 1972. The reason for the referral was either a recent injury or significant disability after an earlier injury. At that time the diagnosis of traumatic brain injury was made on the basis of neurological symptoms and their consistency with the type of injury, whereas neuroradiological examinations were seldom carried out.

From the original group of 210 patients, 76 had died. The inclusion criteria for the remaining 134 patients were 1) a head trauma severe enough to cause traumatic brain injury and causing neurological symptoms (including headache and nausea) lasting at least 1 week and 2) at least one of the following: loss of consciousness for at least 1 minute, posttraumatic amnesia for at least 30 minutes, neurological symptoms (excluding headache and nausea) during the first 3 days after the injury, or neuroradiological findings suggesting traumatic brain injury (e.g., skull fracture, intracerebral hemorrhage). The exclusion criteria were 1) neurological illness before the brain injury, 2) clinical symptoms of a nontraumatic neurological illness that developed after the traumatic brain injury (excluding dementia), 3) insufficient cooperation, or 4) unavailability of medical records.

Of the 134 patients, 13 did not meet the inclusion criteria according to medical records, one patient was excluded because of neurological illness before traumatic brain injury, and two patients did not have available medical records. The remaining 118 patients were contacted by mail, and 88 of them replied. Eighty-three of them met the inclusion criteria, but seven were excluded because of a nontraumatic neurological illness, and 16 refused to participate in the study. The remaining 60 patients formed the study group for this investigation, and they were examined between January 1998 and April 1999. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. The protocol was approved by the Conjoint Ethics Committee of Turku University and Turku University Central Hospital. The characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

To test the representativeness of the study group (N=60), the deceased subjects (N=76) plus the combined group of subjects (N=46) who either refused to participate in the study (N=16) or could not be reached (N=30) were compared with the study group in terms of age, gender, education, severity of traumatic brain injury, and history of harmful alcohol use dichotomized as yes or no (data were missing for 6.7% of the study group, 27.6% of those who were deceased, and 45.7% of those who refused to participate or could not be reached). The only significant differences between the groups, according to analysis of variance (ANOVA), were in age (F=29.42, df=2, 179, p<0.001) and education (F=9.77, df=2, 179, p<0.001). The deceased subjects were significantly older and had less education.

Background data were collected with a specially designed questionnaire containing information on demographic characteristics and traumatic brain injury. The severity of traumatic brain injury was classified on the basis of the duration of posttraumatic amnesia as follows: <1 hour=mild, 1–24 hours=moderate, 1–7 days=severe, and >7 days=very severe. There was no significant difference in the severity of traumatic brain injury between men and women (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.24).

Psychiatric interviews were conducted by a research psychiatrist (S.K.), who was trained to use the instruments. If the interview was considered unreliable (in five patients, 8.3%), the information was checked with a relative. Current (previous month) and lifetime DSM-IV diagnoses of axis I disorders were made on a clinical basis with the aid of the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry interview (version 2.1) (19). Personality disorders were assessed independently of axis I disorders with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (20). We used the DSM-III-R version of SCID-II, because the DSM-IV version of the screening questionnaire was not available in Finnish at the time of our study. A personality disorder was rated as subthreshold if a patient met all but one of the required criteria. Organic personality syndrome was assessed according to DSM-III-R criteria, and it was divided into the following subtypes: labile, aggressive, disinhibited, apathetic, paranoid, and combined. It was rated as definite if it caused clinically significant distress or disability; otherwise it was rated as subclinical. In three of 14 patients (21.4%) given diagnoses of definite or subclinical organic personality syndrome, a relative was reached to confirm the personality change. For the remaining 11 patients, an informant was not available (N=7) or the patient forbade the attempt to contact an informant (N=4). The diagnosis of organic personality syndrome was not applied to patients with dementia.

Cognitive functioning was evaluated by a research psychologist (L.H.) with the Mild Deterioration Battery (18), which measures verbal, visuomotor, and episodic memory performance. The Mild Deterioration Battery consists of eight tests: similarities, digit span, digit symbol, and block design from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (21), the Benton visual retention test (22), immediate recall of 30 paired word associates, and naming time and immediate recall for 20 common objects. A patient received 1 deterioration point if his or her performance on any of the eight tests was 1.5 standard deviations below the norm (18), 2 points if the score was 2.0 standard deviations below the norm, and 3 points if the score was 3.0 standard deviations below the norm. Thus, the maximum total score on the Mild Deterioration Battery was 24 points. On the basis of the total score, each patient was classified as normal (0–1 points), mildly impaired (2–4 points), moderately impaired (5–8 points), severely impaired (9–13 points), or very severely impaired (14 points or more); very severely impaired usually corresponds to clinical dementia. Cognitive impairment was also screened with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (23). The Mild Deterioration Battery and MMSE were not completed for two patients.

Descriptive statistics, such as means, standard deviations, ranges for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables were used to assess the patients’ background characteristics. To test for differences in categorical variables, chi-square tests or, if necessary, Fisher’s exact tests were applied. Continuous variables were analyzed with one-way ANOVA. To avoid multiplicity, Bonferroni adjustment was used. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on binomial distribution for the rates of psychiatric disorders. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS statistical software (24). A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Axis I Disorders

Of the 60 patients assessed, 37 (61.7%, 95% CI=48.2%–73.9%) had had an axis I disorder during their lifetimes and 24 (40.0%, 95% CI=27.6%–53.5%) had a current axis I disorder. Comorbidity among lifetime axis I disorders was observed in 13 (35.1%) of the 37 patients. In 13 of the 60 total patients (21.7%), an axis I disorder was found that had already occurred before the traumatic brain injury. Twenty-nine patients (48.3%, 95% CI=35.2%–61.6%) had an axis I disorder with onset after traumatic brain injury, and five of them had had a different axis I disorder before the injury. The total rates of novel axis I disorders did not differ between men and women (Fisher’s exact test, p=1.00) or among the four severity levels of traumatic brain injury (Fisher’s exact test, p=1.00).

In Table 2, axis I disorders are classified according to their onset in relation to the traumatic brain injury. The most common axis I disorder after traumatic brain injury was major depression: 26.7% (95% CI=16.1%–39.7%) experienced it after traumatic brain injury (which was also the lifetime rate), and 10.0% (95% CI=3.8%–20.5%) had it at the time of the interview. There were no patients with psychotic depression. The rate of major depression after traumatic brain injury was insignificantly higher in women (31.6%, six of 19) than in men (24.4%, 10 of 41) (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.55). There were no significant differences in its occurrence among the four categories of injury severity (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.32).

Novel (and lifetime) panic disorder was diagnosed in 8.3% of the patients (95% CI=2.8%–18.4%), and current panic disorder was diagnosed in 6.7% (95% CI=1.9%–16.2%). Thirteen male patients had had alcohol abuse or dependence during their lifetimes (21.7%, 95% CI=12.1%–34.2%): for seven of them (11.7%, 95% CI=4.8%–22.6%) onset occurred after the traumatic brain injury, and for five (8.3%, 95% CI=2.8%–18.4%) the disorder was present at the time of the interview.

Psychotic disorder with onset after traumatic brain injury was found in four male patients (6.7%, 95% CI=1.9%–16.2%). Two of them had had moderate brain injuries, and the other two had had severe injuries. Three of the four had delusional disorder (5.0%, 95% CI=1.0%–13.9%). Two of them also had dementia. A lifetime (also current) psychotic disorder was observed in five male patients (8.3%, 95% CI=2.8%–18.4%).

Cognitive Impairment

The severity of cognitive impairment as measured with the Mild Deterioration Battery and MMSE is presented in Table 1. Eight of 58 patients (13.8%) had very severe cognitive impairment according to the Mild Deterioration Battery. When they were assessed clinically, three of them were found to have dementia, three had subclinical dementia, one had a current psychotic disorder, and one had a current major depression. They were all male, so the difference between men and women was significant (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.044). There were no significant differences in the occurrence of very severe cognitive impairment among the four levels of brain injury severity (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.21).

Axis II Disorders

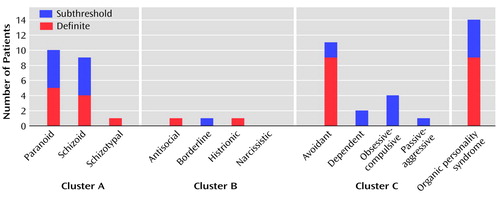

Definite personality disorders were found in 14 patients (23.3%, 95% CI=13.4%–36.0%), and subthreshold disorders were found in an additional 11 patients (18.3%). Five (35.7%) of the 14 patients had more than one definite personality disorder. The rates of definite and subthreshold individual personality disorders are presented in Figure 1. The most prevalent disorders were avoidant (definite in 15.0%, 95% CI=7.1%–26.6%; subthreshold in 3.3%), paranoid (definite in 8.3%, 95% CI=2.8%–18.4%; subthreshold in 8.3%), and schizoid (definite in 6.7%, 95% CI=1.9%–16.2%; subthreshold in 8.3%). Nine patients (15.0%, 95% CI=7.1%–26.6%) had a definite organic personality syndrome, and five of them (55.6%) had a comorbid SCID-II personality disorder. Thus, personality disorder or organic personality syndrome was observed in 18 patients (30.0%). The subtypes of definite organic personality syndrome were as follows: combined, N=5 (labile plus disinhibited, N=4; paranoid plus labile, N=1); disinhibited, N=2; paranoid, N=1; and apathetic, N=1. A subclinical organic personality syndrome was found in five patients (8.3%), the subtypes were as follows: disinhibited, N=2; paranoid, N=2; and apathetic, N=1. There were no significant differences between men and women in the occurrence of definite personality disorders (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.75) or definite organic personality syndrome (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.71). Nor did the four levels of brain injury severity differ from each other in the occurrence of personality disorders (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.50) or organic personality syndrome (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.50).

About one-third of patients with a lifetime axis I disorder (11 of 37, 29.7%) had either a comorbid personality disorder or an organic personality syndrome, and almost two-thirds of the patients with personality disorder or organic personality syndrome (11 of 18, 61.1%) had a lifetime axis I disorder.

Discussion

The main finding of the present study was the high rate of most axis I and II disorders during the 30 years after traumatic brain injury. At present, we do not have epidemiologic data on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Finland according to DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, or ICD-10 criteria. However, in our study group, rates of both lifetime and current axis I disorders were significantly higher than the respective prevalences in the population-based Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) survey (25), which used DSM-III criteria; the rates of lifetime disorders in our study and the ECA survey were 61.7% (95% CI=48.2%–73.9%) and 32.7%, respectively, and the rates of current disorders were 40.0% (95% CI=27.6%–53.5%) and 15.7%. These findings suggest that traumatic brain injury not only temporarily disturbs brain function but may cause decades-long or even permanent vulnerability to psychiatric disorders in some individuals. Correspondingly, Achte et al. (2) found a latency period of more than 10 years in 42% of the cases of psychosis after traumatic brain injury.

In the present study group, the rates of both lifetime (26.7%, 95% CI=16.1%–39.7%) and current (10.0%, 95% CI=3.8%–20.5%) major depression were significantly higher than the prevalences in the ECA survey (5.9% and 2.3%, respectively) (25). Our findings are in line with earlier reports of high rates of major depression after traumatic brain injury (1, 3–5, 8–10). Major depression was observed not only at the early stage after traumatic brain injury but throughout the 30-year follow-up. In accordance with findings in previous studies (1, 4, 5, 9), its occurrence was not significantly related to the severity of the brain injury. There were no patients with dysthymia among our subjects, whereas the rate of dysthymia after traumatic brain injury reported in earlier studies has ranged from 2% to 14% (1, 4, 5, 9). It is possible that brain damage may increase vulnerability to major depression more than susceptibility to dysthymia. The rate of bipolar II disorder (1.7%) was somewhat low compared with the rates of 2% to 17% reported earlier (3, 7–9).

The lifetime and current rates of panic disorder, 8.3% (95% CI=2.8%–18.4%) and 6.7% (95% CI=1.9%–16.2%), respectively, were significantly higher than the prevalences in the ECA survey (1.6% and 0.5%) (25). They support previous reports of an increased rate after traumatic brain injury (1, 8–10). Unlike panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder was unexpectedly rare in our subjects, compared to earlier findings (1, 6, 8–10). We did not find patients with PTSD, a finding contrary to recent reports on its occurrence after traumatic brain injury (9, 10, 12). It is possible that in our patients the heterogeneous symptoms of PTSD did not cluster together 30 years after the accident or that the patients unconsciously avoided recalling symptoms associated with remote traumatic memories.

Lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence was found in 21.7% of the subjects (95% CI=12.1%–34.2%), and current alcohol disorders were present in 8.3% (95% CI=2.8%–18.4%). These figures do not differ significantly from the prevalences of the ECA survey (13.5% and 2.8%, respectively) (25). Our results are in line with two previous reports (1, 10), but higher rates have been reported after traumatic brain injury for alcohol abuse in one small-scale study (8) and for substance use in another study (9). The rarity of drug use in Finland before the 1990s explains its absence in our study group. Moreover, the mean age of our patients was high, 61 years, and the prevalence of alcohol abuse declines with advancing age because of increased mortality and remissions (26).

The rates of lifetime and current psychotic disorders were both 8.3% (95% CI=2.8%–18.4%). They were significantly higher than the prevalences in the ECA survey (1.5% and 0.7%, respectively) (25). Five percent of our patients (95% CI=1.0%–13.9%) had delusional disorder, whereas the estimate for its population prevalence is only 0.03% in DSM-IV. Our figures are in accordance with the rate of 9% for psychoses (2% for paranoid psychoses) after traumatic brain injury found in an early study by Achte et al. (2). In more recent studies (3, 10), only a rate of 1% for schizophrenia after traumatic brain injury was reported. In our subjects, paranoid features were also common on axis II, as was reflected in the rate of 16.6% for definite or subthreshold paranoid personality disorder. Two of the three patients with delusional disorder also had dementia, and both patients had delusions of persecution. About one-half of patients with Alzheimer’s disease have delusions, usually persecutory (27). It is probable that after traumatic brain injury, decreased prefrontal capability to process information makes patients prone to paranoid interpretations.

All eight patients with very severe cognitive impairment were male. This finding cannot be explained by alcohol use in men, because the presence of very severe cognitive impairment according to the Mild Deterioration Battery was not associated with lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence (Fisher’s exact test, p=1.00). Nor were there significant differences in the severity of brain injury between men and women (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.24). The neuroprotective influences of estrogen and progesterone (28) can, at least partially, explain this more favorable outcome after traumatic brain injury in women.

In population studies (29–31) the total prevalence of personality disorders has ranged from 5.9% to 13.5%. The difference in the rate of personality disorders between our study (23.3%; 95% CI=13.4%–36.0%) and the majority of these population studies was substantial. This high rate in our elderly patients is even more striking considering that the prevalence of personality disorders declines with age (30, 32). Our figure falls below the rates for personality disorders after traumatic brain injury reported by Van Reekum et al. (8) (38%) and Hibbard et al. (11) (66%). However, our summed rate of SCID-II personality disorders and organic personality syndrome (30.0%) is close to the former figure. In our study, the most common personality disorders were avoidant (15.0%, 95% CI=7.1%–26.6%), paranoid (8.3%, 95% CI=2.8%–18.4%), and schizoid (6.7%, 95% CI=1.9%–16.2%) personality disorder, while in the population studies, the upper limits of the ranges of prevalences for these disorders have been 1.6%, 7.3%, and 1.6%, respectively (29–31). Also, Hibbard et al. (11) reported that avoidant (26%) and paranoid (26%) personality disorders are common after traumatic brain injury. It seems that traumatic brain injury can expose some individuals to social anxiety, suspiciousness, and detachment. There were only two patients (3.3%) with definite cluster B personality disorders in our group. This is in contrast to the findings of Hibbard et al. (11), who found borderline personality disorder to be the most prevalent disorder after traumatic brain injury (34%). However, in our study, the category of organic personality syndrome that we applied resulted in a group that contained several individuals with labile and disinhibited features resembling behavior in borderline personality disorder. The high age of our patients may also have influenced the number of cluster B disorders, as they tend to decline with advancing age (33).

Organic personality syndrome was relatively common (15.0%, 95% CI=7.1%–26.6%) but clearly less prevalent than personality change in earlier studies (49%–80%) (14–16). However, these figures have probably included patients with all kinds of axis II disorders. The rate of 32% for ICD-10 organic personality disorder reported recently by Franulic et al. (17) is closer to our findings. The severity of brain injury was not associated with the presence of organic personality syndrome, which is in line with the findings of Franulic et al. (17). Although about half of our patients with organic personality syndrome also had an SCID-II personality disorder, we regard organic personality syndrome as a relevant and useful diagnostic category.

The strengths of our study include the assessment of both axis I and II psychiatric disorders with structured instruments, evaluation of cognitive functioning by a sensitive neuropsychological test battery, and to our knowledge, the longest follow-up ever reported. This study has also some limitations. First, although the subjects drawn from the original group were representative, the original patients were referred for neuropsychological evaluation on a clinical basis. For that reason, our conclusions may not be generalizable to all patients with traumatic brain injury. Second, because of incomplete medical records and the lack of systematic neuroradiological examinations at the time of the injury, the information on the nature and location of brain injury and consequently on their association with the development of psychiatric disorders remained insufficient. Third, the reliability of retrospective diagnoses may have been compromised by patients’ memory disturbances. Fourth, as our patients were aged, there were seldom informants available who could report changes following traumatic brain injury about 30 years ago. Therefore, interviewing informants systematically was not possible, which is a limitation particularly in the diagnosis of personality change. Fifth, the small number of subjects and the lack of an age-matched comparison group are shortcomings.

In summary, our results suggest that traumatic brain injury can cause decades-long or even permanent vulnerability to psychiatric disorders in some individuals. Personality disturbances, which were common among our patients, can be difficult to detect and may impair compliance with rehabilitation. Therefore, psychiatric evaluation and follow-up should be included in the routine treatment of traumatic brain injury.

|

|

Received April 13, 2001; revision received Oct. 11, 2001; accepted March 15, 2002. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology, Turku University Central Hospital; and the Departments of Neurology and Biostatistics, University of Turku, Turku, Finland. Address reprint requests to Dr. Koponen, Department of Psychiatry, Turku University Central Hospital, PL 52, FIN-20521 Turku, Finland; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from Turku University Central Hospital and the Research Foundation of Orion Corporation.

Figure 1. Rates of DSM-III-R Definite and Subthreshold Personality Disorders at 30-Year Follow-Up in 60 Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury

1. Fann JR, Katon WJ, Uomoto JM, Esselman PC: Psychiatric disorders and functional disability in outpatients with traumatic brain injuries. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1493-1499Link, Google Scholar

2. Achte KA, Hillbom E, Aalberg V: Psychoses following war brain injuries. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1969; 45:1-18Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Varney NR, Matrzke JS, Roberts RJ: Major depression in patients with closed head injury. Neuropsychology 1987; 1:7-9Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Fedoroff JP, Starkstein SE, Forrester AW, Geisler FH, Jorge RE, Arndt SV, Robinson RG: Depression in patients with acute traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:918-923Link, Google Scholar

5. Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Arndt SV, Starkstein SE, Forrester AW, Geisler F: Depression following traumatic brain injury: a 1 year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 1993; 27:233-243Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Starkstein SE, Arndt SV: Depression and anxiety following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 5:369-374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Starkstein SE, Arndt SV, Forrester AW, Geisler FH: Secondary mania following traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:916-921Link, Google Scholar

8. Van Reekum R, Bolago I, Finlayson MAJ, Garner S, Links PS: Psychiatric disorders after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 1996; 10:319-327Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hibbard MR, Uysal S, Kepler K, Bogdany J, Silver J: Axis I psychopathology in individuals with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1998; 13:24-39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Deb S, Lyons I, Koutzoukis C, Ali I, McCarthy G: Rate of psychiatric illness 1 year after traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:374-378Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Hibbard MR, Bogdany J, Uysal S, Kepler K, Silver JM, Gordon WA, Haddad L: Axis II psychopathology in individuals with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2000; 14:45-61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bryant RA, Marosszeky JE, Crooks J, Gurka JA: Posttraumatic stress disorder after severe traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:629-631Link, Google Scholar

13. Damasio H, Grabowski T, Randall F, Galaburda AM, Damasio AR: The return of Phineas Gage: clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient. Science 1994; 264:1102-1105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. McKinlay WW, Brooks DN, Bond MR, Martinage DP, Marshall MM: The short-term outcome of severe blunt head injury as reported by relatives of injured persons. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1981; 44:527-533Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Thomsen IV: Late outcome of very severe blunt head trauma: a 10-15 year second follow-up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1984; 47:260-268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Brooks N, Campsie L, Symington C, Beattie A, McKinlay W: The five year outcome of severe blunt head injury: a relative’s view. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1986; 49:764-770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Franulic A, Horta E, Maturana R, Scherpenisse J, Carbonell C: Organic personality disorder after traumatic brain injury: cognitive, anatomic and psychosocial factors: a 6 month follow-up. Brain Inj 2000; 14:431-439Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Portin R, Muuriaisniemi M-L, Joukamaa M, Saarijärvi S, Helenius H, Salokangas RKR: Cognitive impairment and the 10-year survival probability of a normal 62-year-old population. Scand J Psychol 2001; 42:359-366Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, Burke J, Cooper JE, Giel R, Jablenski A, Regier D, Sartorius N: SCAN: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:589-593Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1989Google Scholar

21. Wechsler D: Manual for Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. New York, Psychological Corp, 1955Google Scholar

22. Benton AL: The Revised Visual Retention Test. New York, Psychological Corp, 1963Google Scholar

23. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. The SAS System for Windows, version 8.00. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1999Google Scholar

25. Bourdon KH, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Narrow WE, Regier DA: Estimating the prevalence of mental disorders in US adults from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. Public Health Rep 1992; 107:663-668Medline, Google Scholar

26. Vaillant GE: A long-term follow-up of male alcohol abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:243-249Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Deutsch LH, Bylsma FW, Rovner BW, Steele C, Folstein MF: Psychosis and physical aggression in probable Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1159-1163Link, Google Scholar

28. Roof RL, Hall ED: Gender differences in acute CNS trauma and stroke: neuroprotective effects of estrogen and progesterone. J Neurotrauma 2000; 17:367-388Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. De Girolamo G, Reich JH: Epidemiology of Mental Disorders and Psychosocial Problems: Personality Disorders. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1993Google Scholar

30. Cohen BJ, Nestadt G, Samuels JF, Romanoski AJ, McHugh PR, Rabins PV: Personality disorder in later life: a community study. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:493-499Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Samuels JF, Nestadt G, Romanoski AJ, Folstein MF, McHugh PR: DSM-III personality disorders in the community. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1055-1062Link, Google Scholar

32. Fogel BS, Westlake R: Personality disorder diagnoses and age in inpatients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51:232-235Medline, Google Scholar

33. Reich J, Nduaguba M, Yates W: Age and sex distribution of DSM-III personality cluster traits in a community population. Compr Psychiatry 1988; 29:298-303Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar