Diseases of the Mind and Brain

Rett’s syndrome is an illness expressed predominantly in female infants that is caused by mutations in a gene encoding methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2). This protein binds to methylated DNA and may function as a transcriptional repressor by associating with the DNA chromatin-remodeling complexes. The resultant infant syndrome begins in seemingly normal 6- to 12-month-old babies and causes profound mental retardation and premature death across a wide age range (12–40 years). The mental retardation occurs without significant neurodegeneration but rather with a reduction in neuronal size and loss of neuropil throughout gray matter areas, in conjunction with a decrease in white matter. For this illness, only limited information can be collected by studying patients or tissue samples; this information is essential for developing a full understanding of the pathophysiologic processes caused by the gene mutation. Such a mechanistic understanding must be available to develop a rational treatment for these affected infants. However, since Rett’s syndrome is a genetic illness, and we know the specific genetic defect, the syndrome can be reproduced in animals and studied in these models.

Laboratory animals can be created with the same loss of MECP2 function as seen in Rett’s syndrome infants. Scientists have created several lines of mouse mutants in which various parts of the MECP2 gene are deleted in the brain. These mice provide a representative model of the infant condition: they are born neurologically normal and fertile but then develop abnormal behaviors around 4–5 weeks of age; they then regress and die by 8–10 weeks of age. Reduced brain size as well as a reduction in neuronal size and in neuropil are seen in many brain areas, including the neocortex and parts of the limbic system. These MECP2 mutant mice will be directly used in research to develop treatments for Rett’s syndrome.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Tamminga, Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, University of Maryland, P.O. Box 21247, Baltimore, MD 21228; [email protected] (e-mail). Images A–D are courtesy of Dr. T.L. Kemper and Dr. M.L. Baumann. Images E and F are courtesy of Dr. Akbarian.

Rett's Syndrome

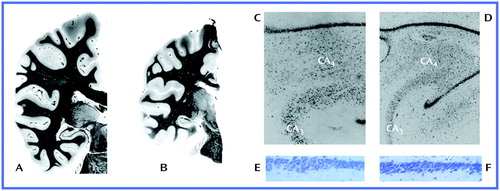

Myelin stains of coronal sections through the parietal and temporal lobes taken from a healthy subject (A) and a Rett’s syndrome patient (B) illustrate the reduction of both gray and white matter seen in Rett’s syndrome. Low-power Nissl-stained sections of the hippocampus at the hilus of dentate gyrus level in a healthy subject (C) and a Rett’s syndrome patient (D) show the reduced neuronal size associated with Rett’s syndrome. Last, high-power Nissl-stained sections from the CA1/CA2 border region of the hippocampus taken from a normal mouse (E) and an MECP2-deficient mouse (F) reveal shrunken, dystrophic, and densely packed neurons in the latter.