Neuropsychiatry and the Future of Psychiatry and Neurology

What is psychiatry? Psychiatry is a continuously evolving concept that has, historically, conveyed widely varying meanings for patients, physicians, and the general public. Joseph B. Martin (1) traced the specialty’s conceptual evolution in America from one predominant theoretical and therapeutic model to another over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. Melvin Sabshin (2) reviewed these successive transitions and indicated that, by the middle of the 20th century, psychiatry had moved from a field based on structural neuropathology to psychoanalysis to community and social psychiatry. He summarized the deleterious effects of these conceptual changes as follows: “The combination of psychiatry’s boundary expansion, the predominance of ideology over science, and the field’s demedicalization began to produce a vulnerability. Many decision makers became skeptical about psychiatrists’ capacity to diagnose and treat patients” (2, p. 1270). Nancy C. Andreasen (3) has written that the revolutionary advances in psychopharmacology, molecular biology, functional brain imaging, and genetics that have been occurring since the end of the 20th century raise the antipodal concern, i.e., that psychiatry could overcorrect with an increasingly narrow biological focus that would endanger the humanism of the field. A potential result of such biological reductionism would be the fragmentation of psychiatric care to a point that the psychiatrist would solely diagnose illnesses and prescribe medications, with a concomitant de-emphasis on the psychological and social aspects of causation and remediation of mental illnesses. Although we do not agree, many concerned psychiatrists and neurologists contend that such a state, wherein there is a neurobiological localization for every illness and the equivalent of “a pill for every problem” has already arrived for psychiatry’s sister specialty, neurology.

The psychobiology model of Adolf Meyer is nearly 100 years old (4), and George L. Engel articulated the biopsychosocial approach to the practice of psychiatry over a quarter century ago (5). We must now ask why neither of these potentially unifying and integrating paradigms for psychiatry has resulted in substantially reduced stigmatization of the mentally ill (6) or sufficient acceptance of psychiatric treatment by patients (7). The answer is clear: neither psychiatry nor its companion field neurology can escape or surmount the fundamental flaw that lies at their very foundations, i.e., the arbitrary and baseless cleavage of brain-based disorders into two disparate medical specialties.

Two reports in this issue of the Journal highlight the conceptual disintegration of separating brain-based disorders into neurological or psychiatric conditions. Koponen et al. evaluated over a period of 30 years the occurrence of psychiatric disorders in patients who had experienced a traumatic brain injury. Each patient had experienced brain trauma of sufficient severity to result in neurological symptoms that had lasted at least 1 week as well as at least one of the following: loss of consciousness for at least 1 minute, posttraumatic amnesia for at least 30 minutes, or neuroradiological findings suggesting traumatic brain injury. The study found that 48.3% developed an axis I disorder subsequent to the brain trauma, including major depression (26.7%), alcohol abuse or dependence (11.7%), panic disorder (8.3%), specific phobia (8.3%), and psychotic disorders (6.7%). Additionally, 23.3% of the patients developed at least one personality disorder following their injuries—avoidant (15.0%), paranoid (8.3%), and schizoid (6.7%) personality disorders were most prevalent. This study is noteworthy in that it documents that the highly prevalent and disabling psychiatric syndromes associated with traumatic brain injury persist for many decades after the injury.

In a second report in this issue of the Journal, Leroi et al. found that the rates of occurrence of cognitive, personality, and mood disorders in patients with degenerative cerebellar disorders and in patients with Huntington’s disease are significantly higher than in people without neurological conditions. Specifically, a strikingly high rate of patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases (77%) and a similar rate of patients with Huntington’s disease (81%) manifested psychiatric disorders; a much lower rate was seen in a group of comparison subjects who were not neurologically impaired (41%). This study not only demonstrates the high coincidence of profound psychiatric disorders in illnesses conventionally conceptualized as neurological but also indicates that the cerebellum and the basal ganglia regions of the brain most commonly associated with motor regulation have critical roles in the modulation of cognition, behavior, and emotion.

Together, these two excellent reports demonstrate several of the many problems inherent in separating psychiatry and neurology into discrete medical specialties. First, the separation perpetuates mind-body dualism that is a perennial source of the public’s confusion about whether or not mental illnesses have biological bases and whether psychiatry is a credible medical specialty. This confusion is also a source of the stigmatization of the mentally ill and leads to a lack of parity in the reimbursement for psychiatric treatments with those for other medical conditions. Second, this separation of the specialties promotes the condensation of complex brain disorders into simplistic categorizations that are based on single symptoms. Prototypic examples include the designation of Parkinson’s disease, which has a high prevalence of psychosis, depression, and dementia (8), as a “movement disorder” and the consideration of schizophrenia, wherein patients suffer from cognitive, mood, and motivational dysfunctions (9), as a “psychotic disorder.” Neither Koponen et al. nor Leroi et al. addressed whether or not the patients in their studies received effective treatment for the psychiatric aspects of their conventionally conceptualized “neurological” disorders. Unfortunately, our experience with patients referred to us with long-standing neurological disorders is that the highly disabling concomitant disorders of mood, behavior, and cognition most frequently go undiagnosed and, therefore, untreated in this population.

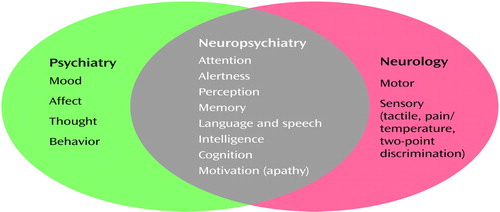

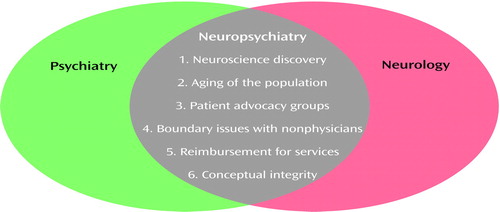

What is neuropsychiatry? As with psychiatry, there is considerable disagreement about just what the concept of neuropsychiatry encompasses. Nonetheless, fundamental to any definition of neuropsychiatry is the indelible inseparability of brain and thought, of mind and body, and of mental and physical (10). As its very name implies, neuropsychiatry is an integrative and collaborative field that eschews specialty-derived, reductionistic categorizations that recognize and address only circumscribed features of a specific brain-based illness. Rather, the field bridges conventional boundaries imposed between mind and matter as well as between intention and function. Most importantly, neuropsychiatry vaults the guild-based theoretical and clinical schisms between psychiatry and neurology. A prominent focus of neuropsychiatry is the assessment and treatment of the cognitive, behavioral, and mood symptoms of patients with neurological disorders. Neuropsychiatrists are also devoted to the care of patients whose symptoms lie in the “gray zone” between the specialties of neurology and psychiatry (Figure 1). Understanding the role of specific brain loci and dysfunctional systems in the etiology and treatment of patients with psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia or bipolar illness is another special interest to neuropsychiatrists. It is important to note that neuropsychiatrists recognize, utilize, and prioritize psychosocial factors—including experiential, psychodynamic, interpersonal, societal, and spiritual—in the understanding and care of all patients. Aware that each of the aforementioned foci of neuropsychiatry should be integral to the practice of both psychiatry and neurology, neuropsychiatrists believe that the re-alliance of the two specialties will best serve both patients and practitioners. We remain confident that the confluence of the six factors illustrated in Figure 2 will move the two fields progressively closer under the intact and integrating conceptual scaffolding of neuropsychiatry.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Stuart Yudofsky, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, BCM 350, Houston, Texas 77030; [email protected] (e-mail)

Figure 1. Areas of Impaired Functioning Addressed by Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neuropsychiatrya

aAdapted from the section introduction by Yudofsky and Hales (11).

Figure 2. Factors Influencing the Future Interface of Psychiatry and Neurologya

aAdapted from the section introduction by Yudofsky and Hales (11).

1. Martin JB: The integration of neurology, psychiatry, and neuroscience in the 21st century. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:695-704Link, Google Scholar

2. Sabshin M: Turning points in twentieth-century American psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1267-1274Link, Google Scholar

3. Andreasen NC: Brave New Brain: Conquering Mental Illness in the Era of the Genome. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001Google Scholar

4. Lidz T: Adolf Meyer and the development of American psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 1966; 123:320-332Link, Google Scholar

5. Engel GL: The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977; 196:129-136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Satcher D: Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, 1999, pp 5-9Google Scholar

7. National Mental Health Association: America’s Mental Health Survey. Alexandria, Va, NMHA, 2001, pp 10-21Google Scholar

8. Lerner AJ, Whitehouse PJ: Neuropsychiatric aspects of dementias associated with motor dysfunction, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 4th ed. Edited by Yudofsky SC, Hales RE. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002, pp 931-937Google Scholar

9. Tamminga CA, Thaker GK, Medoff DR: Neuropsychiatric aspects of schizophrenia. Ibid, pp 989-1020Google Scholar

10. Yudofsky SC, Hales RE: The reemergence of neuropsychiatry: definition and direction. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1989; 1:1-6Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Yudofsky SC, Hales RE: Delirium, dementia, and amnestic and other cognitive disorders, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 3rd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2001, pp 383-386Google Scholar