Childhood Adversities Associated With Risk for Eating Disorders or Weight Problems During Adolescence or Early Adulthood

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A community-based prospective longitudinal study was conducted to investigate the association between childhood adversities and problems with eating or weight during adolescence and early adulthood. METHOD: A community-based sample of 782 mothers and their offspring were interviewed during the childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood of the offspring. Childhood maltreatment, eating problems, environmental risk factors, temperament, maladaptive parental behavior, and parental psychopathology were assessed during childhood and adolescence. Eating disorders and problems with eating or weight in the offspring were assessed during adolescence and early adulthood. RESULTS: A wide range of childhood adversities were associated with elevated risk for eating disorders and problems with eating or weight during adolescence and early adulthood after the effects of age, childhood eating problems, difficult childhood temperament, parental psychopathology, and co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled statistically. Numerous unique associations were found between specific childhood adversities and specific types of problems with eating or weight, and different patterns of association were obtained among the male and female subjects. Maladaptive paternal behavior was uniquely associated with risk for eating disorders in offspring after the effects of maladaptive maternal behavior, childhood maltreatment, and other co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled statistically. CONCLUSIONS: Childhood adversities may contribute to greater risk for the development of eating disorders and problems with eating and weight that persist into early adulthood. Maladaptive paternal behavior may play a particularly important role in the development of eating disorders in offspring.

Previous research has suggested that childhood adversities may contribute to the development of eating disorders. Individuals with eating disorders are more likely than those without eating disorders to report a history of childhood maltreatment (1–3), other chronic or episodic childhood adversities (4–7), and problematic relationships with their parents (1, 8–13). These findings have enabled researchers to generate hypotheses about the role of childhood adversities in the development of eating disorders (14). However, nearly all of the studies that have examined the association between childhood adversities and eating disorders have been cross-sectional case-control investigations. It is problematic to make inferences about risks associated with the onset of eating disorders among individuals in the general population on the basis of cross-sectional studies of patients with eating disorders.

To investigate potential risk factors that may contribute to the development of eating disorders, prospective longitudinal research with a sizable community-based sample is necessary. Potential risk factors must be assessed before the development of the eating disorders. Covariates such as childhood eating problems and childhood temperament that may account for the association between the risk factors and the eating disorders must be controlled statistically. Our review of the literature indicates that no investigation of the association between a wide range of childhood adversities and offspring risk for the development of eating disorders that we located met all of these methodological criteria.

In the study reported here, data from the Children in the Community Study, a prospective longitudinal investigation, were used to examine whether maladaptive parental behavior, childhood abuse and neglect, other childhood adversities, and socioeconomic variables were associated with elevated risk for the development of problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood. Statistical procedures were used to control for the effects of offspring age, childhood temperament, childhood eating problems, parental psychopathology, and co-occurring childhood adversities.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The current analyses were conducted with data from 782 families for whom information was available on childhood adversities and problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood. These families are a subset of 976 randomly sampled families from two upstate New York counties. The mothers were interviewed in 1975, 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993 (15, 16). One randomly selected child from each family was interviewed in 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993. The sample was generally representative of families in the northeastern United States with regard to socioeconomic status and most demographic variables; the sample reflected the region in having high proportions of Catholic (54%) and white (91%) participants (16). The mean age of the 397 male and 385 female offspring in the sample was 6 years (SD=3) in 1975, 14 years (SD=3) in 1983, 16 years (SD=3) in 1985–1986, and 22 years (SD=3) in 1991–1993. Study procedures were approved according to appropriate institutional guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained after the interview procedures were fully explained. The youths and their mothers were interviewed separately, and both interviewers were blind to the responses of the other informant. Additional methodological information is available from previous reports (15, 16).

Assessment

Offspring psychiatric disorders and childhood temperament

The parent and youth versions of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (17) were administered in 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993 to assess offspring psychiatric disorders. Both the parents and the youths were interviewed because the use of multiple informants tends to increase the reliability and validity of psychiatric diagnoses (18, 19). A symptom was considered present if it was reported by either informant. Previous research has indicated that the reliability and validity of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children as employed in the present study are comparable to those of other structured interviews (20).

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children items assessed the diagnostic criteria for eating disorders, as well as a wide range of specific eating and weight problems. Computer algorithms were subsequently developed to determine whether individuals met the DSM-IV criteria for eating disorders. A diagnosis of eating disorder not otherwise specified (e.g., anorexia without amenorrhea, binge eating disorder) was made if clinically significant eating disorder symptoms were present but the full criteria for anorexia nervosa, binge eating disorder, or bulimia nervosa were not met. Participants were defined as obese if their weight was ≥150% of normal body weight and ≥2 standard deviations above the sample mean. Participants were defined as having low body weight if their weight was ≤90% of normal body weight and ≥2 standard deviations below the sample mean. Neither obesity nor low body weight was considered an eating disorder unless the individual had symptoms that met the DSM-IV criteria for an eating disorder. Additional data were drawn from the interviewer’s observations of the child’s behavior during the interview.

Ten dimensions of difficult childhood temperament were assessed by using the Disorganizing Poverty Interview (15) during the 1975 maternal interviews: 1) clumsiness-distractibility, 2) nonpersistence-noncompliance, 3) anger, 4) aggression to peers, 5) problem behavior, 6) temper tantrums, 7) hyperactivity, 8) crying-demanding, 9) fearful withdrawal, and 10) moodiness. Children with severe problems in one or more of these domains were identified as having a difficult temperament. Previous research has supported the reliability and validity of these 10 indices of childhood temperament (21).

Parental psychiatric symptoms

Interview items used to assess maternal psychiatric symptoms in 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986 were obtained from the Disorganizing Poverty Interview, the California Psychological Inventory (22), the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (23), and instruments that assessed maternal alienation (24), rebelliousness (25), and other maladaptive traits (26, 27). Paternal alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and antisocial behavior were assessed during the 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986 interviews by using the Disorganizing Poverty Interview. In addition, lifetime histories of parental anxiety, depressive, disruptive, and substance use disorders were assessed during the 1991–1993 maternal interview by using items adapted from the New York High Risk Study Family Interview (28). Additional data were provided by the interviewer’s observations of the mother’s behavior during the interview. Parental eating disorders were not assessed. Data regarding age at onset permitted identification of maternal and paternal psychiatric disorders that were evident by 1985–1986. Computerized diagnostic algorithms were developed by using the items from these instruments to assess the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for maternal personality disorders, paternal antisocial personality disorder, and maternal and paternal anxiety, depressive, disruptive, and substance use disorders.

Maladaptive parental behavior

The Disorganizing Poverty Interview and the measures of parental child-rearing attitudes and behaviors that were administered during the maternal interviews were used to assess maternal enforcement of rules, the presence of loud arguments between the parents, maternal educational aspirations for the child, maternal possessiveness, maternal use of guilt to control the child, maternal difficulty controlling anger toward the child, parental cigarette smoking, paternal assistance to the child’s mother, paternal role fulfillment, and maternal verbal abuse (15, 29–31). Measures that assessed parental affection toward the child, time spent with the child, and communication with the child were administered in the maternal and offspring interviews in 1983 and 1985–1986 (15, 29, 30). Interview items used to assess maternal punishment and offspring identification with the parents were administered during the maternal and offspring interviews in 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986 (29, 30). Parental home maintenance and maternal behavior during the interview were assessed on the basis of interviewers’ observations. Previous research has supported the construct validity of the measures that were used to assess parental behavior (15, 16, 29–35). The scales and items assessing each type of parental behavior across the three interviews (1975, 1983, and 1985–1986) were dichotomized empirically at the maladaptive end of the scale to identify statistically deviant parental behaviors. To ensure adequate statistical power, parental behavior was defined as deviant if such behavior was at least one standard deviation from the sample mean.

Childhood maltreatment

Youths who had been referred to state agencies, investigated by childhood protective service agencies, and confirmed as being abused or neglected were identified from a central registry. Information about these individuals was abstracted from the registry by a member of the study team. Self-reports of childhood maltreatment were obtained from the offspring in 1991–1993. Official and self-reports were not available for offspring who were under age 18 in 1991–1993 or who had moved out of the state. Maternal interview items that were used to assess childhood neglect were obtained from the Disorganizing Poverty Interview on the basis of correspondence with the items in the cognitive, emotional, physical, and supervision neglect subscales of the Neglect Scale (36). Childhood neglect was considered present if scores were ≥2 standard deviations above the sample mean and if there was clear evidence of parental neglect (e.g., failure to vaccinate the child).

Other childhood adversities and socioeconomic variables

The Disorganizing Poverty Interview was used to assess the following childhood adversities in 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986: death of a parent, disabling parental accident or illness, living in an unsafe neighborhood, low level of parental education, parental separation or divorce, peer aggression, low family income, school violence, the presence of a crime victim in the household, and upbringing by a single parent. Family income was transformed to percentage of the current U.S. poverty levels in 1975, 1983, and 1985–1986. Poverty was defined as mean income below 100% of the U.S. poverty levels. Low level of parental education was defined as less than a high school education for one or both parents. Adversities were considered present if reported at any of the three assessments. Numerous studies have supported the reliability and validity of the Disorganizing Poverty Interview (15, 16).

Data Analytic Procedure

Analyses of contingency tables were conducted to investigate the associations between childhood adversities and eating or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood. An alpha level of 0.01 was adopted to reduce the likelihood of type I error. Logistic and multiple regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether these associations remained significant after the effects of age, difficult childhood temperament, eating problems during childhood, parental psychopathology, and co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether overall levels of maladaptive maternal and paternal behavior were associated with eating disorders in offspring during adolescence or early adulthood after the effects of co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether the overall levels of maladaptive maternal and paternal behavior were associated with the total number of offspring problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood after the effects of co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

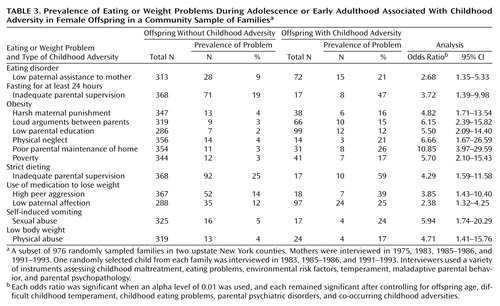

Fifty-two youths (6.6%) received a diagnosis of an eating disorder during adolescence or early adulthood. The frequencies of specific problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood are presented in Table 1. The frequencies of childhood adversities that were uniquely associated with eating or weight problems are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Childhood Adversities and Eating Disorders

Individuals who experienced physical neglect or sexual abuse during childhood were at elevated risk for eating disorders and for several types of eating or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood (Table 2). Low paternal affection toward the child, low paternal communication with the child, low paternal time spent with the child, poverty, and low parental education were each associated with one or more types of eating or weight problems in the offspring during adolescence or early adulthood. These associations remained significant after the effects of age, difficult temperament, childhood eating problems, and parental psychiatric disorders were controlled statistically.

Because there was some temporal overlap between the assessment of childhood maltreatment and adolescent eating and weight problems, we also investigated the association between childhood adversities and problems with eating or weight during early adulthood. Low paternal time spent with the child (odds ratio=1.55, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.06–2.26), low paternal affection (odds ratio=1.78, 95% CI=1.24–2.53), sexual abuse (odds ratio=3.32, 95% CI=1.40–7.82), and physical neglect (odds ratio=4.58, 95% CI=1.99–10.46) were associated with elevated risk for problems with eating or weight during early adulthood. The index of maladaptive paternal behavior was associated with eating or weight problems during early adulthood (r=0.10, df=781, p=0.004). The index of maladaptive maternal behavior was not associated with eating or weight problems during early adulthood.

Maladaptive Maternal and Paternal Behavior

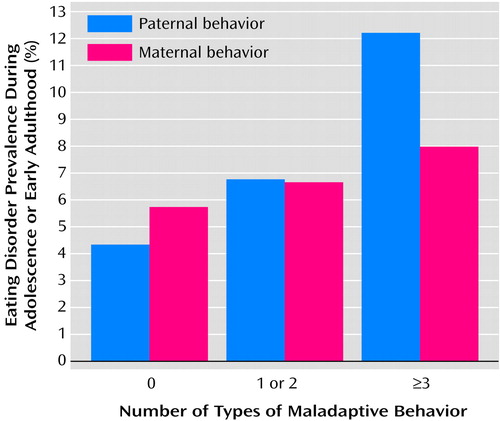

As Figure 1 shows, youths who experienced three or more kinds of maladaptive paternal behavior were approximately three times as likely as youths who did not experience any maladaptive paternal behaviors to have eating disorders during adolescence or early adulthood (χ2=9.49, df=2, p=0.009). The overall association between maladaptive maternal behavior and offspring risk for eating disorders was not statistically significant. The continuous index of maladaptive paternal behaviors remained significantly associated with offspring risk for eating disorders after the effects of co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled statistically.

The association between maladaptive paternal behaviors and offspring eating disorders was partly mediated by low offspring identification with the father. Youths who did not identify with their father were at elevated risk for eating disorders after the effect of maladaptive paternal behavior was controlled statistically (adjusted odds ratio=2.70, 95% CI=1.12–6.49). The association between maladaptive paternal behavior and offspring eating disorders did not remain significant after the effect of low offspring identification with the father was controlled statistically.

The index of maladaptive paternal behaviors was significantly correlated with the total number of eating or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood among the male (r=0.12, df=396, p=0.01) and female (r=0.10, df=384, p=0.04) offspring. The index of maladaptive maternal behaviors was not significantly correlated with the total number of eating or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood in either subsample. This pattern of findings was obtained regardless of whether the mother or the youth provided the data regarding parental behavior. Maladaptive paternal behaviors remained significantly associated with the total number of offspring problems with eating or weight after the effects of co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled statistically (t=2.89, df=777, p=0.004).

The indices of maladaptive maternal behaviors, types of childhood maltreatment, and other childhood adversities and socioeconomic variables were not independently associated with offspring risk for eating disorders after the effects of co-occurring childhood adversities were controlled statistically. However, the index of types of childhood maltreatment was independently associated with strict dieting (odds ratio=1.60, 95% CI=1.16–2.20), recurrent fluctuations in weight (odds ratio=1.58, 95% CI=1.15–2.16), and vomiting (odds ratio=1.89, 95% CI=1.08–3.29), and the index of other adversities was independently associated with obesity during adolescence or early adulthood (odds ratio=1.23, 95% CI=1.06–1.43).

Eating Problems Among Male and Female Offspring

Significant associations between childhood adversities and problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood among the female offspring are presented in Table 3. The effects of the covariates were controlled. In the male subsample, low parental education was associated with elevated risk for obesity (odds ratio=3.60, 95% CI=1.66–7.79), and physical neglect during childhood was associated with elevated risk for use of medication to lose weight (odds ratio=17.50, 95% CI=2.94–104.12) and self-induced vomiting (odds ratio=29.33, 95% CI=4.29–200.39) during adolescence or early adulthood. These associations remained significant after Fisher’s exact tests were conducted and after the effects of the covariates were controlled statistically.

Discussion

The present findings advance our understanding of the association between childhood adversities and risk for eating disorders in several respects. First, our findings indicate that a wide range of childhood adversities tend to be associated with elevated risk for problems with eating or weight during adolescence or early adulthood after the effects of childhood eating problems, difficult childhood temperament, parental psychopathology, and co-occurring childhood adversities are controlled statistically. Further, the findings suggest that there may be unique associations between specific childhood adversities and specific problems with eating or weight and that there may be different patterns of association between adversities and problems with eating or weight among males and females in the general population.

The present findings suggest that maladaptive paternal behavior may play a more important role than maladaptive maternal behavior in the development of eating disorders in offspring. Most of the theoretical literature in this area has focused on the mother-child relationship (37–41). However, our findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that low paternal affection (8), care (9), and empathy (12) and high paternal control (8), unfriendliness (14), overprotectiveness (11), and seductiveness (10) are associated with the development of eating disorders in offspring. Although the fathers were not interviewed in the present study, the findings are not likely to be attributable to reporting bias on the part of the informants. First, the overall rate of maladaptive paternal behavior was not higher than that of maladaptive maternal behavior. Second, the same pattern of findings was obtained with data for paternal behavior that were obtained during the maternal and offspring interviews. Third, maladaptive paternal behavior was not more strongly associated with offspring risk for other psychiatric disorders than was maladaptive maternal behavior (34). Our findings also suggest that low paternal identification may partially mediate the association between maladaptive paternal behavior and eating disorders in offspring. It will be of interest for future research to further investigate the mechanisms that underlie this association.

The present findings are consistent with previous cross-sectional research suggesting that childhood maltreatment (1–3) and maladaptive parental behavior (8–13, 42) may contribute to the development of eating disorders and that many types of childhood adversities may be associated with risk for problems with eating or weight (4–7, 43). Because the present findings are based on prospective longitudinal data, they provide more compelling support for these hypotheses. Moreover, our findings support the hypothesis that the causes of eating disorders tend to be heterogeneous and multifactorial (44). However, because previous research has provided inconsistent findings about the nature of the association between childhood adversities and the development of weight problems, it will be important for future research to investigate this association more extensively.

The limitations of the present study merit consideration. There were not enough cases to permit analyses of the relationships between childhood adversities and specific eating disorders. Therefore, we have reported associations between childhood adversities and several different types of eating and weight problems. To have enough statistical power to conduct separate analyses with the female and male subsamples, data on eating and weight problems during adolescence and early adulthood were pooled, and there was some overlap in the periods during which some of the risk factors and outcomes were assessed. To address this concern, we have reported associations between childhood adversities and problems with eating or weight during early adulthood. Despite these limitations, the present findings provide a detailed, systematic, and methodologically rigorous contribution to the literature.

|

|

|

Received Feb. 6, 2001; revisions received May 18 and July 26, 2001; accepted Aug. 15, 2001. From Columbia University and the New York State Psychiatric Institute; and Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Johnson, Box 60, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY, 10032; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. Association of Maladaptive Maternal and Paternal Behavior With Prevalence of Eating Disorders During Adolescence or Early Adulthood in 782 Offspring in a Community Sample of Familiesa

aA subset of 976 randomly sampled families in two upstate New York counties. Mothers were interviewed in 1975, 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993. One randomly selected child from each family was interviewed in 1983, 1985–1986, and 1991–1993.

1. Fairburn CG, Welch SL, Doll HA, Davies BA, O’Connor ME: Risk factors for bulimia nervosa: a community-based case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:509-517Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. De Groot J, Rodin GM: The relationship between eating disorders and childhood trauma. Psychiatr Annals 1999; 29:225-229Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Connors ME, Morse W: Sexual abuse and eating disorders: a review. Int J Eat Disord 1993; 13:1-11Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Horesh N, Apter A, Lepkifker E: Life events and severe anorexia nervosa in adolescence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 91:5-9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Schmidt U, Humfress H, Treasure J: The role of general family environment and sexual and physical abuse in the origins of eating disorders. Eur Eating Disorders Rev 1997; 5:184-207Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Welch SL, Doll HA, Fairburn CG: Life events and the onset of bulimia nervosa: a controlled study. Psychol Med 1997; 27:515-522Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Troop NA, Treasure JL: Setting the scene for eating disorders, II: childhood helplessness and mastery. Psychol Med 1997; 27:531-538Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wonderlich S, Ukestad L, Perzacki R: Perceptions of nonshared childhood environment in bulimia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:740-747Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Kendler KS, Walters EE, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: The structure of the genetic and environmental risk factors for six major psychiatric disorders in women: phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, bulimia, major depression, and alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:374-383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rorty M, Yager J, Rossotto E, Buckwalter G: Parental intrusiveness recalled by women with a history of bulimia nervosa and comparison women. Int J Eat Disord 2000; 28:202-208Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Calam R, Waller G, Slade PD, Newton T: Eating disorders and perceived relationships with parents. Int J Eat Disord 1990; 9:479-485Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Steiger H, Van der Feen J, Goldstein C, Leichner P: Defense styles and parental bonding in eating-disordered women. Int J Eat Disord 1989; 8:131-140Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Horesh N, Apter A, Ishai J, Danziger Y, Miculincer M, Stein D, Lepkifker E, Minouni M: Abnormal psychosocial situations and eating disorders in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:921-927Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Wonderlich S, Klein MH, Council JR: Relationship of social perceptions and self-concept in bulimia nervosa. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:1231-1237Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kogan LS, Smith J, Jenkins S: Ecological validity of indicator data as predictors of survey findings. J Soc Service Res 1977; 1:117-132Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Cohen P, Cohen J: Life Values and Adolescent Mental Health. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1996Google Scholar

17. Costello EJ, Edelbrock CS, Duncan MK, Kalas R: Testing of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in a Clinical Population: Final Report to the Center for Epidemiological Studies, NIMH. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh, 1984Google Scholar

18. Bird HR, Gould M, Staghezza B: Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:78-85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Piacentini J, Cohen P, Cohen J: Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: are complex algorithms better than simple ones? J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 20:51-63Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Cohen P, O’Connor P, Lewis SA, Malachowski B: A comparison of the agreement between DISC and K-SADS-P interviews of an epidemiological sample of children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:662-667Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Cohen P, Brook JS: Family factors related to the persistence of psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry 1987; 50:332-345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Gough HG: The California Psychological Inventory. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1957Google Scholar

23. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L: The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci 1974; 19:1-15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Cohen P, Struening EL, Muhlin G, Genevie LE, Kaplan SR, Peck HB: Community stressors, mediating conditions, and well-being in urban neighborhoods. J Community Psychol 1982; 10:377-391Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Smith G, Fogg CP: Psychological antecedents of teenager drug use, in Research in Community and Mental Health: An Annual Compilation of Research, vol 1. Edited by Simmons R. Greenwich, Conn, JAI Press, 1979, pp 87-102Google Scholar

26. Zuckerman M, Eysenck S, Eysenck HJ: Sensation seeking in England and America: cross-cultural, age, and sex comparisons. J Consult Clin Psychol 1978; 46:139-149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Pearlin S, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT: The stress process. J Health Soc Behav 1981; 22:377-386Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Squires-Wheeler E, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L: The New York High Risk Study Family Interview. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1986Google Scholar

29. Avgar A, Bronfenbrenner U, Henderson CR: Socialization practices of parents, teacher, and peers in Israel: kibbutz, moshav, and city. Child Dev 1977; 48:1219-1227Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Schaefer ES: Children’s reports of parental behavior: an inventory. Child Dev 1965; 36:413-424Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Brook JS, Whiteman M, Gordon AS, Brook DW: Paternal determinants of female adolescents’ marijuana use. Dev Psychol 1984; 20:1032-1043Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Wagner BM, Cohen P: Adolescent sibling differences in suicidal symptoms: the role of parent-child relationships. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1994; 22:321-337Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Smailes E, Skodol A, Brown J, Oldham J: Childhood verbal abuse and risk for personality disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. Compr Psychiatry 2001:42:16-23Google Scholar

34. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Smailes E, Brook J: The association of maladaptive parental behavior with psychiatric disorder among parents and their offspring. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:453-460Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Johnson JG, Smailes EM, Cohen P, Brown J, Bernstein DP: Associations between four types of childhood neglect and personality disorder symptoms during adolescence and early adulthood: findings of a community-based longitudinal study. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:171-187Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Straus MA, Kinard EM, Williams LM: The Neglect Scale. Durham, University of New Hampshire, Family Research Laboratory, 1995Google Scholar

37. Likierman M: On rejection: adolescent girls and anorexia. J Child Psychotherapy 1997; 23:61-80Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Humphrey LL, Stern S: Object relations and the family system in bulimia: a theoretical integration. J Marital Fam Ther 1988; 14:337-350Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Marsden P: Demeter and Persephone: fear of cannibalistic engulfment in bulimia. Br J Psychother 1997; 13:318-326Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Hirsch M: The body as a transitional object. Psychother Psychosom 1994; 62:78-81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Strober M, Humphrey LL: Familial contributions to the etiology and course of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. J Consult Clin Psychol 1987; 55:654-659Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Chatoor I, Egan J, Getson P, Menvielle E: Mother-infant interactions in infantile anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1988; 27:535-540Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Wamala SP, Wolk A, Orth-Gomer K: Determinants of obesity in relation to socioeconomic status among middle-aged Swedish women. Prev Med 1997; 26:734-744Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Rosen DS, Neumark Sztainer D: Reviews of options for primary prevention of eating disturbances among adolescents. J Adolesc Health 1998; 23:354-363Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar