Should the DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria for Conduct Disorder Consider Social Context?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The text of the DSM-IV states that a diagnosis of conduct disorder should be made only if symptoms are caused by an internal psychological dysfunction and not if symptoms are a reaction to a negative environment. However, the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria are purely behavioral and ignore this exclusion. This study empirically evaluated which approach—the text’s negative-environment exclusion or the purely behavioral criteria—is more consistent with clinicians’ intuitive judgments about whether a disorder is present, whether professional help is needed, and whether the problem is likely to continue. METHOD: Clinically experienced psychology and social work graduate students were presented with three variations of vignettes describing youths whose behavior satisfied the DSM-IV criteria for conduct disorder. The three variations presented symptoms only, symptoms caused by internal dysfunction, and symptoms caused by reactions to a negative environment. The clinicians rated their level of agreement that the youth described in the vignette had a disorder, needed professional mental health help, and had a problem that was likely to continue into adulthood. RESULTS: Youths with symptoms caused by internal dysfunction were judged to have a disorder, and those with a reaction to a negative environment not to have a disorder. The difference was not explained by the clinicians’ judgments of the youths’ need for professional help or the expected duration of symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: The clinicians’ judgments supported the validity of the DSM-IV’s textual claim that a diagnosis of conduct disorder is valid only when symptoms are due to an internal dysfunction.

A fundamental challenge to psychiatric diagnosis is the formulation of diagnostic criteria that distinguish true psychiatric disorders from nondisordered but negative psychological conditions, often referred to as “problems in living.” This distinction has importance for concerns ranging from treatment choice to epidemiological prevalence estimates. Use of diagnostic criteria that mistakenly classify problems of living as disorders may give rise to false positive diagnoses—that is, diagnoses of mental disorder in individuals whose behavior satisfies the correctly applied diagnostic criteria, but who in fact do not have a disorder.

The task of avoiding false positive diagnoses is complicated by the fact that the distinction between disorder and nondisorder is itself subject to dispute. DSM-III addressed this problem by offering a definition of mental disorder that, with minor changes, also appeared in DSM-III-R and DSM-IV. This definition was intended to explicate an intuitive concept of disorder that underlies medical judgments and is widely shared by health professionals—that the symptoms of a disorder are due to an internal process that is not functioning as expected (i.e., an internal dysfunction). Thus, for example, the diagnosis of mood disorder assumes that internal mechanisms that regulate affect are failing to perform their expected function, whereas sadness that is appropriate to a loss is not a disorder because internal regulating mechanisms are functioning as expected.

Despite the DSM’s attempt to clarify the intuitive concept of disorder, critics of the DSM regularly claim that its diagnostic criteria incorrectly classify as disorders conditions that in reality are normal responses to difficult circumstances. This study examines the extent to which diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder correctly identify psychiatric disorders and exclude cases that are better conceptualized as normal but negative psychological conditions. We focus on conduct disorder partly because it is among the most common DSM diagnoses made in children and adolescents. Clinical prevalence rates for conduct disorder are reported to range from one-third to more than two-thirds among child and adolescent patients in clinic and hospital studies (1–4), and community lifetime prevalence rates for adolescents of 10% to 17%, according to DSM-III, DSM-III-R, and DSM-IV criteria, have been reported (5, 6). We first review concerns about the potential overdiagnosis of conduct disorder and then report results of an empirical study that examined whether clinicians’ intuitive diagnostic judgments are more consistent with the concept of disorder expressed in the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria or with the narrower concept suggested by the definition of disorder in the text of DSM-IV.

DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria Versus DSM-IV Text

Internal dysfunctions potentially involved in conduct disorder include the failure of mechanisms involved in the capacity for empathy, guilt, moral conscience, and impulse control. The text of DSM-IV acknowledges that the DSM-IV criteria for conduct disorder can be satisfied by youths who have no such dysfunction. The DSM-IV criteria require, for youths under age 18, the presence of at least three of 15 behavioral symptoms accompanied by social or academic impairment. Consider, for example, the following two cases: a 12-year-old boy joins a gang for self-protection in a threatening neighborhood and over a period of time engages in gang-related antisocial activity; a 13-year-old girl avoids familial sexual abuse by repeatedly lying, staying out at night, and running away from home. In both cases the youth qualifies for a conduct disorder diagnosis, according to the DSM-IV criteria, but may have no internal dysfunction. Should such adolescents be considered to have a mental disorder? The DSM-IV offers two contradictory answers.

The text of DSM-IV states that a diagnosis of conduct disorder should be made only if symptoms are caused by an underlying dysfunction and not if the problem is due only to a reaction to a problematic environment:

Concerns have been raised that the Conduct Disorder diagnosis may at times be misapplied to individuals in settings where patterns of undesirable behavior are sometimes viewed as protective (e.g., threatening, impoverished, high-crime). Consistent with the DSM-IV definition of mental disorder, the Conduct Disorder diagnosis should be applied only when the behavior in question is symptomatic of an underlying dysfunction within the individual and not simply a reaction to the immediate social context.…It may be helpful for the clinician to consider the social and economic context in which the undesirable behaviors have occurred. (p. 88; emphasis added)

The requirement that symptoms should be due to an internal dysfunction directly expresses the key concept of the DSM’s definition of mental disorder:

Whatever its original cause, it must currently be considered a manifestation of a behavioral, psychological, or biological dysfunction in the individual. Neither deviant behavior…nor conflicts that are primarily between the individual and society are mental disorders unless the deviance or conflict is a symptom of a dysfunction in the individual. (pp. xxi–xxii, emphasis added)

However, the DSM-IV’s actual diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder, which are used by most clinicians and researchers, are inconsistent with both the textual commentary and the DSM-IV’s own definition of mental disorder. The criteria make no reference to an exclusion related to a negative environment and allow for classification as conduct disorder of behaviors that are not caused by dysfunction. DSM-IV provides an alternative V code category for nondisordered adolescent antisocial behavior: V71.02, child or adolescent antisocial behavior. However, this classification covers “isolated antisocial acts…not a pattern of antisocial behavior” (p. 684). There is no V code category for patterns of antisocial behavior that are nondisordered.

There are two points to keep in mind in considering the exclusion of non-dysfunction-caused behaviors from the conduct disorder diagnosis. First, “dysfunction” refers to conditions in which something has gone wrong with the functioning of some internal psychological mechanism or structure. It does not refer to maladaptive behavior per se; one can behave maladaptively in various circumstances (e.g., in one’s marriage or at work because of boredom) without having an internal dysfunction or disorder.

Second, the fact that antisocial behaviors are environmentally caused does not by itself imply the absence of disorder. Environmental stressors often cause disorders; for example, posttraumatic stress disorder may be triggered by sexual abuse, and major depression by real loss. Surely exposure to a negative environment can cause internal dysfunction in empathy, impulse control, or moral development that in some children leads to antisocial behaviors. The distinction made in the DSM-IV text is not simply between behaviors caused by internal versus environmental factors, but between behaviors caused by internal dysfunction, which itself might originate from exposure to negative environments, versus behaviors that are a response to a negative environment without the involvement of any dysfunctional internal mechanisms.

This distinction is not always easy to make in practice because many of the same problematic environments—e.g., threatening, impoverished, high crime—that can cause genuine dysfunction and disorder can also cause nondisordered children to react with antisocial behavior. For example, deprived environments may cause enduring biological dysfunctions in empathy or impulse control that lead to antisocial behaviors, but the same environments may also cause psychiatrically normal youths to reasonably choose to act in socially undesirable ways out of motives of self-protection or social conformity. Although clinicians may find it difficult to make these causal inferences, the DSM-IV requires clinicians to make other such judgments, including whether symptoms are caused by other mental disorders, general medical conditions, or substance use.

False Positive Diagnoses

The DSM-IV’s textual exclusion from the diagnosis of conduct disorder of some reactions to negative environments reflects a long history of concern about making an incorrect diagnosis of mental disorder in children who display non-dysfunction-caused antisocial behavior. These concerns go back at least to the writing of Anna Freud (7), who noted,

Some children run away from home because they are maltreated, or because they are not tied to their families by the usual emotional bonds.…Here, the cause of the deviant behavior is rooted in the external conditions of the child’s life and is removed with improvement of the latter. In contrast to this simple situation, there are other children who wander or are truant not for external but for internal reasons. (p. 111)

Contemporary researchers of diverse perspectives have echoed Freud’s concerns that a diagnosis of conduct disorder may be mistakenly made in nondisordered youths. For example, Moffitt (8) argued that adolescence-limited antisocial behavior is often nonpathological, a normal response to the disparity in modern society between youths’ physical maturity and the lack of responsible adult roles. Quay (9) said of such antisocial behavior, “There is little, if any, reason to ascribe psychopathology to youths manifesting…an adjustive response to environmental circumstances” (p. 131). In an influential analysis, Richters and Cicchetti (10) pointed out the potential for false positive diagnoses in DSM-III-R conduct disorder criteria and argued that even Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn would likely qualify for DSM conduct disorder diagnoses. They concluded that “Most scientists are probably not committed to the assumption that the behavioral syndrome defined by conduct disorder is necessarily the product of an underlying mental disorder” (p. 23), citing Paul Meehl’s observation that psychiatrically normal people can learn wrong values.

The correctness of the DSM-IV’s textual negative-environment exclusion, which attempted to address these concerns, is controversial. At a 1995 NIMH workshop on the status of conduct disorder as a mental disorder, several participants claimed that researchers should continue to make diagnoses of conduct disorder solely on the basis of the formal DSM-IV behavioral criteria, which seemed to them to have adequate validity. Moreover, some recent accounts of the concept of mental disorder imply, contrary to the textual exclusion and to the DSM-IV’s definition of mental disorder, that internal dysfunction is not part of the intuitive concept of disorder (11, 12) and that antisocial conduct represents a mental disorder even when no internal dysfunction is present (13).

The question of whether DSM-IV’s conduct disorder criteria or its textual commentary more accurately reflect the concept of disorder potentially has broad implications for other categories, such as mood and anxiety disorders. If deviations from homeostasis in reaction to environmental stressors are recognized as nondisorders, that might help resolve the problem of apparently inflated prevalence rates for some disorders in major epidemiological studies (14). The study reported here offers empirical data relevant to this controversy.

Study Purpose

This study addresses the following question: Are clinicians’ intuitive diagnostic judgments more in accord with the behavioral criteria for the DSM-IV diagnosis of conduct disorder or with DSM-IV’s text guidelines that require internal dysfunction? On the basis of the DSM’s definition of mental disorder and Wakefield’s conceptual analysis of disorder as harmful dysfunction (15, 16)—both of which imply that internal dysfunction is necessary for disorder—as well as the results of an earlier pilot study involving primarily nonclinicians (17), we predicted that clinicians 1) would tend to judge environmental-reactive antisocial behaviors to be nondisorders even when they satisfied conduct disorder criteria and 2) would tend to judge antisocial behaviors induced by internal dysfunction to be disorders. That is, we predicted that clinicians would agree that internal dysfunction, and not solely antisocial behavior, is necessary for disorder.

Both need for professional help (11, 18) and duration of symptoms (14) have been suggested as criteria for disorder and have been cited in epidemiological discussions as potential validators of caseness that can eliminate false positive classifications. Thus, if clinicians classify children who do not have an internal dysfunction as nondisordered, it might be argued that such judgments are made not because these children lack dysfunction per se but because they seem to have transient symptoms or do not seem to require professional care. We focus on this issue in additional analyses that address the following question: Are youths who are judged to need professional help or to have problems of a chronic duration nonetheless judged to be nondisordered if they are considered not to have an internal dysfunction?

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 62 psychology and 55 social work graduate students in clinical courses at Rutgers University, University of California at Los Angeles, and Adelphi University. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. The study design was approved by the institutional review boards at Rutgers University and the University of California at Los Angeles. The subjects were respondents in the courses who met two conditions ensuring clinical knowledge: 1) they had completed a course on DSM-IV diagnosis, and 2) they had at least 1 year of mental health clinical experience. The mean length of clinical experience for both professions was about 4 years (3.7 years, SD=2.4, and 3.9 years, SD=4.3, respectively). The decision to include clinicians from the professions of psychology and social work was made both because of the subjects’ accessibility and because these professions deal with the great majority of youths who exhibit antisocial behavior.

Case Vignettes

Data for this study consisted of subjects’ judgments about experimentally manipulated case vignettes describing youths who display antisocial behaviors that satisfy the diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV conduct disorder. Some vignettes explain the behavior as an adaptive response to a negative environment, and others suggest internal dysfunction as the cause of the behavior.

Vignettes featuring one of two hypothetical youths—Carlos, a 12-year-old Mexican immigrant, and Judy, a 13-year-old white girl—were prepared in three versions, one of which presented information on behavioral symptoms satisfying the DSM-IV conduct disorder criteria and the others of which included information suggesting that the symptoms were related either to a negative environment or to internal dysfunction. Vignettes are available upon request.

Symptom-only vignettes

Symptom-only vignettes presented demographic and symptom information satisfying DSM-IV conduct disorder criteria but provided no information suggesting the cause of the symptoms. The vignettes were constructed to satisfy DSM-IV’s requirement of at least three symptoms in the past year and one in the past 6 months. Carlos displays four DSM-IV symptoms (often bullies or threatens his classmates, often initiates physical fights, has used a baseball bat as a weapon in a schoolyard fight, and has often been truant), and Judy displays six (has broken into someone else’s car, often lies to escape her responsibilities around the house, has shoplifted, often stays out until late at night despite parental prohibitions, has run away from home overnight more than once, and is often truant from school). Although these symptoms clearly imply social impairment, to ensure that the vignettes conveyed the DSM-IV’s requirement of role impairment for a diagnosis of conduct disorder (“the disturbance in behavior causes clinically significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning” [p. 91]), the vignettes included explicit statements that Carlos’s bullying and fighting “has seriously limited his social relationships” and that Judy’s frequent truancy “has markedly impaired her academic performance.”

Results for symptom-only vignettes are reported for comparative purposes because the behaviors depicted satisfy DSM-IV conduct disorder criteria, although we made no predictions about how the study subjects would rate these vignettes. The symptom-only vignettes formed the first paragraph of the vignettes that presented information on negative environment and internal dysfunction.

Negative-environment vignettes

Negative-environment vignettes included a paragraph offering an environmental explanation of the problematic behavior. For Carlos, the negative environment is a threatening gang-divided neighborhood to which he responds by adopting a tough attitude, joining a gang for protection, and engaging in gang-sanctioned antisocial behavior. For Judy, the negative environment is threatened sexual abuse by a family member whom she attempts to evade. Given the conceptual focus of our study, we formulated negative-environment vignettes to indicate environmental causation as unambiguously as possible. For example, we stated that Judy stayed out at night against her parents’ wishes to avoid her abuser and that Carlos used a baseball bat as a weapon in a fight because gang members on both sides did that and he could be expelled from the gang or suffer worse consequences if he did not take part.

Internal-dysfunction vignettes

Internal-dysfunction vignettes included additional information suggesting that the antisocial behavior is likely caused by internal dysfunction. For example, additional information indicated that Carlos’s aggression was disproportionate in intensity and duration to environmental threats, that it was directed relatively indiscriminately at those in his own as well as opposing gangs, and that the problem continued unabated even when he spent several months in a more benign environment.

Instrument and Procedure

Each of the 117 subjects responded to a questionnaire containing two vignettes, one featuring Carlos and one featuring Judy, that represented one of three different conditions (symptom-only, negative-environment, internal-dysfunction), with a randomized order of presentation. Thus, 233 responses were available to be analyzed (two per subject; one was unusable due to incomplete data). Order effect analyses and analyses of the responses to the first vignette seen by each subject indicated that reacting to more than one vignette did not substantially influence subjects’ patterns of response.

After reading each of the two vignettes, the clinicians were asked to rate the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with the following three clinical judgments: 1) “According to my own view, this youth has a mental/psychiatric disorder.” (We did not ask whether the youth’s condition met DSM-IV’s conduct disorder criteria, but rather whether in the clinician’s own view the youth had a disorder.) 2) “This youth needs some kind of professional mental health help.” 3) “This youth’s problematic behavior is likely to continue into adulthood.” Each item was rated on a Likert-type ordinal scale ranging from 1, strongly agree, to 6, strongly disagree. For clinical relevance, we collapsed responses into agree (strongly, moderately, and mildly agree) and disagree (mildly, moderately, and strongly disagree). Percentage of agreement is reported. Because the rates of agreement on presence of a disorder did not significantly differ between social work and psychology students on any of the six vignettes (Fisher’s exact test or Yates-corrected χ2=0.00 to 0.67, df=1, 0.41<p<1.00), the results for the two professions were pooled.

Results

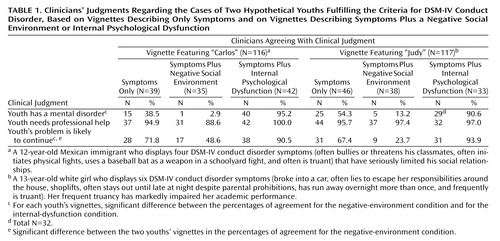

Table 1 presents the clinicians’ frequency of agreement with each of the three clinical judgments for each case vignette.

Diagnosis of Mental Disorder

Our primary prediction was confirmed: the clinicians’ judgments about the presence of mental disorder were strongly influenced by the distinctions between the negative-environment and the internal-dysfunction vignettes. Although all vignettes presented behaviors that satisfied the DSM-IV criteria for conduct disorder, the clinicians overwhelmingly agreed that the youths described in the internal-dysfunction vignettes had mental disorders (vignette featuring Carlos: 95.2%; vignette featuring Judy: 90.6%) but almost never agreed that the youths described in negative-environment vignettes had mental disorders (vignette featuring Carlos: 2.9%; vignette featuring Judy: 13.2%). The differences in percentage of agreement between the negative-environment and internal-dysfunction conditions were significant for the vignettes featuring both youths (χ2=65.48, df=1, p<0.001, two-tailed; χ2=41.73, df=1, p<0.001, two-tailed, respectively). The clinicians responded to symptom-only vignettes with intermediate rates of agreement about the presence of a disorder (vignette featuring Carlos: 38.5%; vignette featuring Judy: 54.3%).

Need for Treatment

As Table 1 indicates, the youths in all three vignette conditions were judged to need professional help (range=88.6% to 100%). Clinicians overwhelmingly agreed that the youths described in the negative-environment vignettes needed professional treatment, even though they were judged not to have a mental disorder by almost all clinicians.

Symptom Duration

Table 1 shows that for both youths, the problem described in the internal-dysfunction vignette, which was almost always judged a disorder, was also almost always judged likely to be of chronic duration. The differences in percentage of agreement between the internal-dysfunction and negative-environment conditions were significant for both youths (χ2=16.43, df=1, p<0.001, two-tailed; χ2=35.44, df=1, p<0.001, two-tailed, respectively). However, nondisordered problematic behaviors were also frequently judged likely to be of chronic duration. Only 2.9% of the clinicians judged Carlos’s problem in the negative-environment vignette to indicate mental disorder, but fully 48.6% judged the problem likely to continue into adulthood. For Judy, the difference was less marked (13.2% versus 23.7%, respectively). The judgments of chronic duration in the negative-environment condition were the only ratings with a significant difference between the vignette featuring Carlos and the vignette featuring Judy (χ2=4.92, df=1, p<0.05, two-tailed). Presumably the clinicians believed that Judy’s family situation is likely to change as she grows older, whereas Carlos’s threatening neighborhood and his reaction to this condition are unlikely to change.

Discussion

We tested whether clinicians’ intuitive judgments about the presence of disorder are more consistent with the DSM-IV’s text, which requires an internal dysfunction for a conduct disorder diagnosis, or with the DSM conduct disorder diagnostic criteria, which have no such requirement. As predicted, clinicians overwhelmingly judged antisocial behaviors that satisfy DSM-IV conduct disorder criteria but are responses to a negative environment to be nondisordered, whereas they overwhelmingly judged the same behaviors to be disordered when additional information suggested that the cause is an internal dysfunction. This study thus provides evidence that the inference that there exists an internal dysfunction is a necessary component of making a valid diagnosis of conduct disorder.

Furthermore, consistent with the DSM’s convention of providing V codes for nondisordered behavior that warrants clinical attention, we found that clinicians frequently judged nondisordered youths whose troubles were due to problematic environments to need professional help. Thus, the need for treatment did not necessarily imply disorder. In addition, judgments of nondisorder did not necessarily coincide with expectations that symptoms would be transient; chronic responses to long-term environmental stressors were often considered nondisordered. This finding suggests that duration criteria would have limited utility in addressing the problem of false positive conduct disorder diagnoses. It also suggests that the inference regarding internal dysfunction itself, rather than other commonly suggested properties, shapes clinicians’ intuitive judgments about the presence of disorder.

The fact that clinicians’ concept of disorder appears to better correspond to DSM-IV’s negative-environment exclusion than to its formal diagnostic criteria poses several challenges. If the DSM-IV text is correct, as our data suggest, then research and epidemiological samples that are based on the conduct disorder criteria are of unknown heterogeneity with respect to disorder status, introducing problems of interpretation, generalizability, and validity. It is important to establish how often false positive diagnoses occur in different settings (i.e., clinical or epidemiologic survey populations), whether there are different treatment implications for cases of disorder versus nondisorder, and whether risk-factor and etiological research need to take this distinction into account.

The study has several limitations. The three vignette conditions were designed to differ markedly to test competing hypotheses about how clinicians conceptualize disorder. This factor may partly explain the magnitude of the findings. The subjects were psychologists and social workers in advanced training who had an average of 4 years of clinical experience. Unfortunately, psychiatrists were not included. Research on clinical judgment has suggested that clinically experienced advanced graduate students are unlikely to differ substantially in their clinical judgments from more experienced clinicians (19). We plan further studies to test whether these results can be replicated in groups of more experienced mental health professionals, including psychiatrists. We examined responses to only two kinds of environmental causes of behavior that are symptomatic of conduct disorder—threatening neighborhood and threatened familial abuse. Responses to other kinds of situations remain to be examined. Finally, studies are needed to identify which information provided in the case vignettes determined the judgments about the presence of disorder. Despite these limitations, the results are sufficiently robust to suggest that the predicted effects of social context on the judgment of dysfunction and disorder are real.

How should the problem of false positive conduct disorder diagnoses suggested in the text of DSM-IV be dealt with in DSM-V? The question is important because a provisional solution for conduct disorder may provide a model for addressing false positive diagnoses related to a negative environment in other diagnostic categories. Our results suggest that one possible response—to add clinical significance requirements, such as role impairment (20–22)—may be inadequate as a general solution. The diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV conduct disorder already include a clinical significance criterion regarding role impairment. Thus, the clinicians in our study judged youths as nondisordered who satisfied symptomatic and clinical significance (role impairment) criteria. The role-impairment requirement was designed to eliminate false positive diagnoses in cases in which symptoms are so mild that they cause no significant harm to the individual, but even normal reactions to problematic environments often involve substantial role impairment. The psychiatrically normal child who reacts to a dangerous neighborhood by joining a gang or who runs away from home to escape the threat of sexual abuse may well be socially or academically impaired as a result, despite the nonpathological nature of the condition.

Another possible response is better clinical training to ensure that clinicians and researchers apply the textual exclusion when it is appropriate. The adequacy of this response is limited by the fact that in some clinical and research settings and other contexts, the DSM-IV’s formal diagnostic criteria may be used as the sole basis for classification decisions.

An alternative proposal, suggested by work on false positive diagnoses (23, 24), is to incorporate a negative-environment exclusion clause modeled on the DSM-IV text directly into the DSM-V diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder. Such an exclusion clause would require the clinician to judge on the basis of history and other information whether the patient’s symptoms are best explained as a normal response to a negative social environment or as the result of internal dysfunction. As a provisional formulation, such an exclusion clause might read, “The symptomatic behavior is not adequately accounted for as a direct, adaptive reaction to a negative social context.”

An important research question concerns the reliability of clinicians’ judgments about social context as a sufficient cause of symptoms in actual clinical practice. The reliability of such judgments, like the reliability of psychiatric diagnosis in general, may be modest. However, that would not be reason to ignore this valid clinical distinction in the diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder.

The formulation, operationalization, and use of negative-environment exclusion clauses pose serious challenges, but so did the formulation, operationalization, and use of the formal diagnostic criteria pioneered in DSM-III. If the DSM-IV criteria for conduct disorder can lead to false positive diagnoses, as our results suggest, then pursuit of an adequate exclusion criterion for a nondisordered reaction to a negative environment is an integral part of the quest started in DSM-III to formulate necessary and sufficient criteria for the valid diagnosis of mental disorders.

|

Received May 25, 2000; revisions received Sept. 15, 2000, and Feb. 5 and July 19, 2001; accepted Aug. 15, 2001. From the School of Social Work and the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J.; and the Department of Social Welfare, University of California, Los Angeles. Address reprint requests to Dr. Wakefield, 309 W. 104 St., Number 9C, New York, NY 10025; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grant MH-42917-02. The authors thank Robert Spitzer for comments on the manuscript, Burt Stillwagon for assistance with data analysis, and Derek Hsieh for assistance with data collection and instrument construction.

1. Kazdin A, Siegel T, Bass D: Drawing upon clinical practice to inform research on child and adolescent psychotherapy: a survey of practitioners. Prof Psychol Res Pr 1990; 21:189-198Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Robins LN: Epidemiological approaches to natural history research: antisocial disorders in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1981; 20:566-680Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Weinstein SR, Noam GG, Grimes K, Stone K, Schwab-Stone M: Convergence of DSM-III diagnoses and self-reported symptoms in child and adolescent inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29:627-634Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lahey BB, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Christ MAG, Green S, Russo MF, Frick PJ, Dulcan M: Comparison of DSM-III and DSM-III-R diagnoses for prepubertal children: changes in prevalence and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29:620-626Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Robins LN, Tipp J, Przybeck T: Antisocial personality, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991, pp 258-290Google Scholar

6. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive: National Comorbidity Survey Data & Documentation. http://www.icpsr. umich.edu/SAMHDA/ncsdat.htmlGoogle Scholar

7. Freud A: The Writings of Anna Freud, vol 4: Normality and Pathology in Childhood: Assessments of Development. New York, International Universities Press, 1965Google Scholar

8. Moffitt TE: Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 1993; 100:674-701Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Quay HC: Patterns of delinquent behavior, in Handbook of Juvenile Delinquency. Edited by Quay HC. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1987, pp 118-138Google Scholar

10. Richters JE, Cicchetti D: Mark Twain meets DSM-III-R: conduct disorder, development, and the concept of harmful dysfunction. Dev Psychopathol 1993; 5:5-29Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Kendell RE: What are mental disorders? in Issues in Psychiatric Classification: Science, Practice, and Policy. Edited by Freedman AM, Brotman R, Silverman I, Hutson D. New York, Human Sciences Press, 1986, pp 23-45Google Scholar

12. Lilienfeld SO, Marino L: Mental disorder as a Roschian concept: a critique of Wakefield’s “harmful dysfunction” analysis. J Abnorm Psychol 1995; 104:411-420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lilienfeld SO, Marino L: Essentialism revisited: evolutionary theory and the concept of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 1999; 108:400-411Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Regier DA, Kaelber CT, Rae DS, Farmer ME, Knauper B, Kessler RC, Norquist GS: Limitations of diagnostic criteria and assessment instruments for mental disorders: implications for research and policy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:109-115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Wakefield JC: The concept of mental disorder: on the boundary between biological facts and social values. Am Psychol 1992; 47:373-388Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wakefield JC: Disorder as harmful dysfunction: a conceptual critique of DSM-III-R’s definition of mental disorder. Psychol Rev 1993; 99:232-247Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Kirk SA, Wakefield JC, Hsieh D, Pottick K: Social context and social workers’ judgment of mental disorder. Soc Serv Rev 1999; 73:82-104Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Regier DA, Narrow WE: Defining psychopathology with epidemiologic and clinical reappraisal data, in Redefining Psychopathology in the 21st Century. Edited by Helzer JE. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association (in press)Google Scholar

19. Garb HN: Studying the Clinician: Judgment Research and Psychological Assessment. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1999Google Scholar

20. Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Erkanli A, Stangl DK, Tweed DL: The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: functional impairment and serious emotional disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1137-1143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, Davies M, Piacentini J, Schwab-Stone ME, Lahey BB, Bourdon K, Jensen PS, Bird HR, Canino G, Regier DA: The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA Study (Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders Study). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:865-877Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Bird HB, Yager TJ, Staghezza B, Gould M, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M: Impairment in the epidemiological measurement of childhood psychopathology in the community. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29:796-803Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Spitzer RL, Wakefield JC: The DSM-IV diagnostic criterion for clinical significance: does it help solve the false positives problem? Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1856-1864Abstract, Google Scholar

24. Wakefield JC: Diagnosing DSM-IV, part 1: DSM-IV and the concept of mental disorder. Behav Res Ther 1997; 35:633-650Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar