Personality Profiles in Eating Disorders: Rethinking the Distinction Between Axis I and Axis II

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Like other DSM-IV axis I syndromes, eating disorders are diagnosed without respect to personality, which is coded on axis II. The authors assessed the utility of segregating eating disorders and personality pathology and examined the extent to which personality patterns account for meaningful variation within axis I eating disorder diagnoses. METHOD: One hundred three experienced psychiatrists and psychologists used a Q-sort procedure (the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure-200) that assesses personality and personality pathology to describe a patient they were currently treating for bulimia or anorexia. Data were subjected to a cluster-analytic procedure (Q-analysis) to determine whether patients clustered into coherent groupings on the basis of their personality profiles. Categorical and dimensional personality diagnoses were then used to predict measures relevant to adaptation and etiology, controlling for axis I diagnosis. RESULTS: Three categories of patients emerged: a high-functioning/perfectionistic group, a constricted/overcontrolled group, and an emotionally dysregulated/undercontrolled group. This categorization demonstrated substantial incremental validity beyond axis I diagnosis in predicting eating disorder symptoms, adaptive functioning (Global Assessment of Functioning scores and history of psychiatric hospitalization), and etiological variables (sexual abuse history). CONCLUSIONS: Axis I symptoms are a useful component, but only one component, in the accurate diagnosis of eating disorders. Classifying patients with eating disorders by eating symptoms alone groups together patients with anorexic symptoms who are high functioning and self-critical with those who are highly disturbed, constricted, and avoidant, and groups together patients with bulimic symptoms who are high functioning and self-critical with those who are highly disturbed, impulsive, and emotionally dysregulated. These distinctions may be relevant to etiology, prognosis, and treatment.

Clinical observation has long suggested a link between personality and eating disorders. Research has consistently linked anorexia (particularly when the patient does not also have bulimic symptoms) to personality traits such as introversion, conformity, perfectionism, rigidity, and obsessive-compulsive features (1). The picture for bulimia is more mixed. Traits such as perfectionism, shyness, and compliance have consistently emerged in studies of individuals with bulimia or with anorexia, although research has often found bulimic patients to be extroverted, histrionic, and affectively unstable (2).

Research on personality disorders has also examined the relation between eating disorders and personality and has documented considerable, but highly variable, rates of comorbidity, ranging from 21% to 97% for the presence of any personality disorder in patients with various eating disorder diagnoses (2, 3). Conversely, patients with personality disorders have a higher than normal prevalence rate for eating disorders (4). The situation is similar for many axis I disorders, such as mood and anxiety disorders, for which comorbidity with axis II disorders hovers around 50% (e.g., reference 5).

Interpreting the comorbidity of eating disorders and personality disorders is complex, in part because of the multiple possible meanings and causes of comorbidity (see reference 6). For example, comorbidity could reflect 1) simple random co-occurrence of multiple different syndromes in psychiatric patients; 2) distinctions in the DSM-IV between axis I and axis II syndromes that do not mirror, or capture important characteristics of, these disorders and their distribution in the population; or 3) common pathology underlying multiple phenotypically distinct disorders. Thus, the comorbidity seen between eating disorders and personality disorders could reflect the possibility 1) that many patients have the random misfortune of having two or more disorders, at least one of which is on axis I and another on axis II, 2) that anorexic and bulimic behaviors are symptomatic expressions of personality pathology and hence that distinctions regarding syndromes, states, and traits embodied in the distinction between DSM-IV axis I and axis II may be problematic with respect to eating disorders, or 3) that some common genetic or environmental diathesis underlies both eating disorders and personality disorders.

The first possibility (random co-occurrence) seems unlikely because of the low probability of such high rates of co-occurrence between axis I and axis II disorders that have relatively low base rates in the population. The second and third hypotheses, which are, practically speaking, difficult to distinguish, both have some limited empirical support. According to one theory, which links personality pathology in eating disorders to specific forms of neurotransmitter dysregulation, anorexia and bulimia lie at opposite ends of a personality continuum defined by compulsivity at the anorexic end and impulsivity at the bulimic (3). This theory addresses the fact that patients with anorexia are most frequently diagnosed with cluster C (anxious/avoidant) personality disorders, whereas bulimic patients are more likely to receive cluster B (dramatic/erratic) diagnoses. One of the most consistent findings has in fact been the association of bulimia with borderline personality disorder (3, 7, 8). Although this hypothesis makes sense of much of the data, the empirical research relating eating disorders and personality disorders is highly inconsistent (see reference 2), with many studies failing to find any clear and specific relationship between personality variables and the two classes of eating disorders (e.g., references 9, 10).

Perhaps the greatest problem for a theory linking anorexia with one personality style and bulimia with another is the extensive comorbidity of anorexic and bulimic symptoms with each other. If certain core personality traits are associated with, or contribute to, specific eating disordered behavior, and these personality traits are in many respects polar opposites, how one individual could display both classes of symptoms is difficult to explain. In fact, patients who have a lifetime history of both disorders or who have concurrent symptoms of both disorders (DSM-IV anorexia, binge-eating/purging type) are more likely to receive a personality disorder diagnosis than patients with either bulimia or anorexia (restricting type), and their personality disorder diagnoses are equally likely to be in cluster B or cluster C (8). Individuals with anorexia, binge-eating/purging type or with a history of both anorexia and bulimia, who we hereafter refer to as bulimic anorexic patients tend to show severe and diffuse pathology and to be more impaired than people with either anorexia, restricting type, alone or with bulimia alone (2–11).

One possible explanation for the substantial inconsistency across studies, as well as the problems presented by patients with a history of both disorders, is that these two axis I categories may indeed be linked to personality factors but may be heterogeneous (12). According to this explanation, personality variables may be highly relevant to understanding eating disorders, but more than one type of personality structure can generate or contribute to the symptoms of each disorder. One type of patient might become anorexic because she is competitive and perfectionistic, another might become anorexic because she is afraid of her impulses and is attempting to prove to herself that she can regulate even the most insistent of drives, another might use anorexia as a form of self-punishment or a way of regulating feelings of being out of control (perhaps after impulsive eating binges, which themselves can be efforts to regulate distress), and still another might develop anorexia as a phenotypic expression of an underlying mood disorder. Inconsistencies across studies in the characteristics of patients with anorexia or bulimia could thus reflect idiosyncratic sampling procedures, such as whether the patients are inpatients, outpatients, or college students.

Some evidence for this possibility comes from investigations of “multi-impulsive” versus “uni-impulsive” bulimic individuals (13). Multi-impulsive persons with bulimia display several impulsive behaviors (e.g., stealing, substance abuse) in addition to binge eating; uni-impulsive patients have binge eating as their only symptom or behavior that could be described as impulsive. Empirically, multi-impulsive bulimic individuals have significantly greater rates of borderline personality disorder and mood disorders than uni-impulsive bulimic individuals (14). Further, the cycles of binge eating and purging of persons with comorbid borderline personality disorder and bulimia (who tend to be multi-impulsive) have different effects on mood than the cycles of persons with bulimia and no comorbid borderline personality disorder (15). Thus, these two groups may represent very different kinds of patients, even though the eating disorder symptoms of multi-impulsive patients with comorbid borderline personality disorder and bulimia do not typically differ from those of their uni-impulsive counterparts without comorbid borderline personality disorder.

The literature on uni- versus multi-impulsive bulimia thus provides an example of two possible subtypes of eating disorder within the general classification of bulimia nervosa that may not be readily differentiated by their eating symptoms. They may, however, differ in personality, etiology, or function of symptoms. If heterogeneous subgroups are grouped together in different ratios in different studies—such as patients who are highly impulsive with those who are not impulsive or those who are even highly constricted—this could not only produce inconsistent findings across studies but could also obscure clinically relevant information about etiology, prognosis, or treatment response.

A clearer understanding of the relation between eating disorders and personality disorders is particularly important, given that individuals with comorbid personality pathology have a more severe course, greater psychological distress, greater mood disturbance, and a slower recovery than those without comorbid personality disorders (8, 16, 17). In addition, patients with characteristics associated with personality disorders—such as elevations on multiple MMPI scales, disturbances in social functioning, and low scores on measures of ego strength—similarly tend to have a poor prognosis (18–20).

Addressing the association of eating disorders and personality is complicated by methodological difficulties, such as the potential confounding of personality patterns that reflect low body weight (versus those that may contribute to the development of anorexic symptoms) and limitations of the self-report and structured interview measures typically used to assess personality (see references 21–24). The aim of the current study was to use a clinically sensitive personality instrument to address three questions:

1. Do patients with current and lifetime diagnoses of anorexia, bulimia, or both differ in personality pathology?

2. Do eating-disordered patients naturally cluster into groups on the basis of personality pathology, and do these clusters map onto axis I diagnoses?

3. Does a classification system reflecting empirically derived personality profiles predict criterion variables, particularly measures of adaptive functioning and etiology, as well as or better than axis I classification?

Method

Subjects

Participants in this study were psychiatrists and psychologists who indicated a willingness to participate in a practice research network. Although the use of clinician-report measures instead of structured interviews has been unusual in psychiatric research, clinical observation has several advantages when quantified with psychometrically sound instruments (23–25). Clinicians tend to be sophisticated observers who see the patient longitudinally and can often offer more informed, expert judgments than either patients themselves (who lack psychiatric training and normative comparisons) or interviewers who see the patient for 90 minutes or less and may not have a professional degree or extensive experience in psychiatry or psychology. Clinicians can, of course, be biased by their theoretical preconceptions; however, all observers have theories and hence potential biases, such as the intuitive theories patients hold about themselves (i.e., their conscious self-concepts, through which their answers to questionnaires and structured interviews are always filtered). Several factors led us to prefer psychiatrically and clinically experienced observers for the present study. These factors include the relatively “hard” nature of the symptoms of eating disorders (particularly in patients who have presented for treatment and hence are motivated to discuss their symptoms), the absence of shared theories about the nature of personality disturbance in different kinds of eating disorder, the possibility of drawing from clinicians with diverse training experiences (psychiatrists and psychologists) and theoretical orientations, prior research with trained observers demonstrating that clinicians’ responses do not tend to be highly influenced by theory when they are asked to use a Q-sort instrument to describe a specific patient (26, 27), and the problematic nature of asking patients direct questions about complex and often socially undesirable personality processes (22, 25).

The clinicians were initially selected from the registers of practicing clinicians from the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association and reflected a range of theoretical orientations (on recruitment of the network, see reference 23). Of the 176 clinicians contacted who indicated that they were currently treating, or had treated within the last 6 months, a female patient with either anorexia or bulimia nervosa, 103 provided data, for a response rate of roughly 60%. Each clinician described one patient.

The respondents were paid an honorarium of $40 for their participation. We asked two-thirds to describe a patient with bulimia and one-third to describe a patient with anorexia. (The decision to request descriptions of unequal numbers of bulimic and anorexic patients reflected prior research findings and clinical experience suggesting greater heterogeneity among patients with bulimic symptoms.) Given the high prevalence rates of the disorders among female patients relative to male patients, we asked the clinicians to describe a female patient to avoid gender confounds.

For both diagnoses, we asked the clinicians to describe a patient who met full DSM-IV criteria for the disorder. To minimize inaccurate diagnosis of binge-eaters without bulimia (i.e., patients who alternate between restricting and overeating but do not perform compensatory activities that meet diagnostic criteria), we specified a history of purging as an inclusion criterion for bulimic patients. With respect to personality assessment, clinicians were asked to focus on enduring traits and not momentary state characteristics or changes that had occurred with treatment and to consult their notes from early in treatment if necessary.

The research design was approved by the institutional review board of the Cambridge Hospital, Cambridge, Mass. Because the survey respondents were licensed practitioners with M.D.’s and Ph.D.’s and did not provide identifying information on patients, no consent form was deemed necessary.

Measures

The clinicians completed a questionnaire that asked for 1) demographic information about themselves, including their discipline, years of experience, and theoretical orientation and 2) information about the patient’s demographic characteristics, eating history, current weight and eating patterns, history of hospitalization, lifetime history of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, developmental history (e.g., history of physical and sexual abuse), and up to three axis I diagnoses. The clinicians also provided a 1–7 rating of the extent to which the patient had characteristics of each of the DSM-III-R and DSM-IV personality disorders (1=not at all, 4=has some features, and 7=fully meets criteria), which we hereafter refer to as personality disorder ratings. Next, they described the patient’s enduring personality patterns using the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure–200 (SWAP-200) Q-sort. (As part of a study of affect regulation in eating disorders, clinicians also completed an affect regulation Q-sort, the Affect Regulation and Experience Q-Sort [27], to describe the patient’s enduring patterns of affectivity and affect regulation.)

The SWAP-200 (23, 24) is a 200-item Q-sort designed to assess personality and personality pathology. The instrument consists of a set of personality-descriptive statements, each of which may describe a given person well, somewhat, or not at all. The statements are printed on separate index cards, and an observer with a thorough knowledge of the subject sorts (rank orders) the statements into categories, from those that are inapplicable or not descriptive to those that are highly descriptive.

Clinicians sorted the 200 statements into eight categories. The first category, which is assigned a value of 0, contains statements the clinician judges irrelevant or inapplicable; the last category, which is assigned a value of 7, contains statements that are highly descriptive. Intermediate categories contain statements that apply to varying degrees. The SWAP-200 thus provides a numeric score ranging from 0 to 7 for each of 200 personality-descriptive items, quantifying expert observation with a standard language. The items are written in a manner close to the data (e.g., “Tends to be passive and unassertive” or “Has an exaggerated sense of self-importance”), and items that require inference about internal processes are stated without jargon (e.g., “Tends to blame others for own failures or shortcomings; tends to believe his/her problems are caused by external factors”). Thus, the SWAP-200 can be used by clinicians regardless of their theoretical orientation.

Items for the SWAP-200 were derived from several sources, including DSM-III-R and DSM-IV axis II criteria, clinical literature on personality disorders, input from several hundred clinicians, research on personality disorders, research on normal personality traits and psychological health, and pilot interviews (26). Development of the item set was an iterative process that took approximately 7 years and used standard psychometric methods, such as eliminating redundant items and items with minimal variance. Perhaps most important, the item set reflects the feedback of more than 1,000 clinicians, who used the item set to describe actual patients. Each time a clinician used the instrument, we asked whether he or she was able to describe the things that were psychologically important about the patient. We added, edited, rewrote, and revised items on the basis of this clinician feedback, then asked new clinicians to describe new patients. We repeated this process until most clinicians could answer “yes” most of the time.

Providing a diagnosis by using the SWAP-200 entails correlating a patient’s 200-item Q-sort profile with empirically derived prototypes of criterion groups. Doing so yields a series of scores that index the extent to which the patient matches each prototype (e.g., the extent to which the patient matches a prototype of histrionic personality disorder). For the assessment of personality disorders, this procedure yields a T-score profile similar to an MMPI profile, except that the profile is based on expert judgment rather than self-report. The instrument yields both dimensional and categorical diagnoses. It also yields specific factor scores on personality traits such as hostility, subclinical thinking disturbance, and dissociation.

Research thus far supports the validity and reliability of the instrument in predicting 1) clinician diagnoses; 2) objective indicators of personality dysfunction such as suicide attempts; 3) overall level of adaptation, assessed by measures such as the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale from DSM-IV; and 4) various developmental and genetic history variables (23, unpublished 1999 paper of D. Westen and J. Shedler). For example, in a recent study of a large group of patients with personality disorders, 40% of patients in the upper fifth percentile in subclinical thought disorder (schizotypy) factor scores had a genetic history of psychosis, whereas none of the patients in the lower fifth percentile did (unpublished 1999 paper of D. Westen and J. Shedler). Similarly, analysis of links between etiological variables and the psychopathic-antisocial factor supported several predictions, including 1) a positive association with developmental history of physical abuse, 2) a sex-linked association with alcohol and illicit drug abuse in biological relatives for male subjects only, and 3) a predicted negative correlation with anxiety disorders in biological relatives.

Statistical Analysis

We tested our hypotheses as follows. First, after initial validity checks on diagnosis, we examined the relation between axis I classification and axis II pathology using t tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA). The purpose of the analyses was to determine whether patients with current or lifetime diagnoses of anorexia, bulimia, or both differed in dimensional measures of axis II pathology made with the SWAP-200.

Second, to cluster patients into naturally occurring groupings based on personality pathology, we applied an empirical clustering technique, Q-analysis (28) (also called Q-factor analysis or inverse factor analysis). Q-analysis identifies groups of patients who are similar to one another and dissimilar to patients in other groups. The technique has been used successfully in studies of normal personality (28–31) and in studies of personality disorders (23). Q-analysis can be understood by comparison with conventional factor analysis (or principal components analysis, which is computationally similar and typically yields similar results [32]). Factor analysis is used when a data set contains many variables that appear to be redundant measures of a few underlying dimensions (factors). The technique identifies groups of variables that are highly similar to one another but dissimilar to others. Q-analysis uses the same algorithms as factor analysis, except that it creates groupings of people, not variables. Thus, Q-analysis, as applied here, identifies groups of patients who share personality characteristics that distinguish them from patients in other groups. The groups, called Q-factors, represent empirically derived diagnostic groupings. Whereas factor analysis isolates a small number of items that measure a shared trait, Q-analysis makes use of all 200 items in the SWAP-200 when clustering cases, and thus takes into account configurations of personality characteristics across a broad range of items. These items assess multiple domains of functioning, including patterns of thought, feeling, motivation, and behavior.

Q-factor analysis can be used to create either dimensional diagnoses (by correlating each subject’s profile with an empirically derived prototype or Q-factor and converting the correlation to a T-score or similar metric) or categorical diagnoses (by establishing a cutoff above which a subject is considered to be a member of the Q-factor or category, on the basis of the magnitude of this correlation or the size of the subject’s loading on each Q-factor). Thus, we created dimensional scores for each subject by correlating the subject’s 200-item SWAP-200 profile with the empirically derived prototypes generated by Q-analysis; we refer to these dimensional scores hereafter as personality Q-scores. We refer to subjects’ categorical personality diagnoses, based on cutoffs described below, as personality Q-factor diagnoses.

Next, to assess the extent to which classification based on personality could predict level of functioning, and whether it could do so as well or better than axis I classification, we employed the following strategies. We measured level of functioning by means of 1) the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and 2) history of psychiatric hospitalization for both eating disorders and other psychiatric problems. We then performed three analyses:

1. We used correlational analysis to examine the association between personality Q-scores, which index the extent to which the patient’s profile matches each empirically derived prototype, and the two measures of level of functioning.

2. Treating the personality Q-factor diagnoses categorically rather than dimensionally, we used ANOVA and chi-square analysis to examine the association between subjects’ categorical eating disorder personality diagnosis (personality Q-factor diagnosis) and level of functioning.

3. To examine the incremental validity of these personality configurations above and beyond axis I diagnosis, we used hierarchical multiple regression to predict level of functioning from personality classification, holding axis I classification constant.

Finally, to test whether the personality groupings differ in etiology, we used the same strategy to examine the relation between personality Q-scores (dimensional diagnoses) and personality Q-factor groupings (categorical diagnoses) and history of sexual abuse, which has been linked in prior research to eating disorders.

We relied on two data-analytic strategies throughout. First, rather than analyzing the data on the basis of either categorical or dimensional personality diagnoses (i.e., that patients either fall into discrete categories or differ quantitatively on the extent to which they are characterized by various features), we treated the data both ways. This allowed us to assess the extent to which similar findings emerged with both the complete study group (in dimensional analyses) and relatively “pure” (categorical) subgroups.

Second, in testing group differences, we made a priori predictions using contrast analysis (33). Contrast analysis maximizes power in predicting differences between groups, minimizes the likelihood of spurious findings by specifying hypotheses in advance, and allows researchers to ask highly specific (one degree of freedom) questions (e.g., about the relative order of group means) rather than global questions that are usually of less theoretical interest (e.g., whether group means differ in some unspecified way). In the analyses that follow, we used the following contrast weights. When predicting that the mean for one group would be higher than the means for the other two groups (with no expectation of differences between the latter groups), we used the weights 2, –1, –1. (Alternatively, if we predicted that the mean of one group was lower than the other two, we would use the weights –2, 1, 1.) If we predicted the mean for group x>the mean for group y>the mean for group z, we used the contrast weights 1, 0, –1 (or, conversely, –1, 0, 1, where the predicted order of means was the opposite).

Results

Study Group Characteristics

Data were provided by 103 clinicians. Group sizes for the analyses varied because of missing data (e.g., six clinicians misunderstood the Q-sort instructions, and others failed to complete specific items, such as the patient’s lifetime history of anorexia, lifetime history of bulimia, personality disorder ratings, or demographic variables). All data considered missing or unusable were identified in advance, prior to data analysis.

Respondents were psychiatrists (39.4%) and psychologists (60.6%). A total of 40.6% were female, and 97.1% were Caucasian. The respondents were, on average, highly experienced, with a mean of 17.6 years (SD=9.2) of practice after psychiatry residency or psychology licensure. With respect to theoretical orientation, 45.2% described themselves as psychodynamic, 29.8% as eclectic, 16.3% as cognitive behavioral, 4.8% as biological, and 1.9% as systemic. The patients had been in treatment with the reporting clinician for a mean of 22 sessions (SD=27). Thus, the clinicians constituted a highly experienced and diverse group and knew their patients quite well.

All of the patients were female, with a mean age of 30.0 years (SD=8.8) and a mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score of 58.2 (SD=16.3). Ninety-five percent of the patients were Caucasian. With respect to socioeconomic status (measured with a 4-point scale), 2.9% were described as poor, 33.0% as working class, 54.4% as middle class, and 7.8% as upper class. In terms of education, 3.8% had not completed high school, 17.3% were high school graduates, 35.6% had completed some college, 24.0% had graduated from college, and 19.2% had attended or completed graduate school. These demographic characteristics resemble those reported elsewhere for patients with eating disorders.

With respect to axis I diagnosis, 25.3% of the clinicians responded to our request to describe a patient currently diagnosed with anorexia, and 74.7% were asked to describe a patient with bulimia. We refer to these diagnoses as primary current diagnoses. On the basis of more specific data provided by respondents, we were able to classify patients according to more specific DSM-IV diagnoses: anorexia, restricting type, N=13; anorexia, binge-eating/purging type, N=35; and bulimia, N=45 (purging type, N=42, and nonpurging type, N=3). (Data necessary for making DSM-IV diagnoses were missing for 10 patients.) We refer to these diagnoses hereafter as specific current axis I diagnoses. According to clinicians, 17 subjects had a past history of only anorexia (without binge eating or purging), 49 had a history of only bulimia, and 35 had a history of both disorders. (Data were missing for two patients.) We refer to these diagnoses hereafter as lifetime diagnoses (anorexia, bulimia, or bulimia-anorexia).

As for axis I comorbidity, depression was common: 30 patients had a lifetime history of major depression, 21 had a current primary or secondary diagnosis of dysthymia, and 14 had an unspecified mood disorder. No other diagnoses were present in more than six patients, although six patients were diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, and five with posttraumatic stress disorder. Grouped either by current or lifetime diagnosis, patients did not differ significantly in socioeconomic status or level of education, although patients with a lifetime diagnosis of both disorders (bulimia-anorexia) tended to have lower educational attainment.

Validity Check

The symptoms of anorexia and bulimia are relatively clear, and the patients in this study group were all in treatment for eating disorders. Nevertheless, as a validity check, we used t tests to compare patients with a primary current diagnosis of anorexia or bulimia and ANOVA to compare patients with a lifetime diagnosis of one or both disorders on symptoms that should distinguish them.

In all cases, differences were large and consistent with expectations. With respect to weight on entering treatment relative to ideal body weight (where 1=more than 20% below, 2=10%–20% below, 3=normal, 4=10%–20% above, and 5=more than 20% above), means for patients with a lifetime diagnosis of anorexia, bulimia, and both disorders were 1.4 (SD=0.51), 3.7 (SD=1.0), and 2.1 (SD=1.3), respectively (F=39.4, df=2, 97, p<0.0001). For number of binges per week (ranging from 1=none to 6=more than three times per week), the means were 1.2 (SD=0.5), 3.0 (SD=1.4), and 2.7 (SD=1.4), respectively (F=12.5, df=2, 98, p<0.0001). For purge frequency, rated with the same rating scale that was used for number of binges per week, the means were 1.3 (SD=0.6), 2.9 (SD=1.7), and 2.7 (SD=1.4), respectively (F=7.5, df=2, 97, p=0.001). Similar patterns emerged when we categorized patients on the basis of the primary current diagnosis (anorexia or bulimia).

We thus have good reason to presume relatively accurate diagnoses, particularly in light of the length of time the clinicians knew the patients. Because comparisons categorizing the patients by primary current diagnosis (anorexia or bulimia), specific current axis I diagnosis (anorexia, restricting type; anorexia, binge-eating/purging type; and bulimia), and lifetime diagnosis (anorexia, bulimia, or bulimia-anorexia) produced largely redundant results, and there seems little theoretical or empirical reason to categorize patients based on the disorder with which they happened to present to this particular clinician at this particular time, we present here primarily the data on lifetime diagnosis and indicate any analyses for which the data for current diagnoses yielded different patterns of results.

Axis I Diagnosis and Personality Pathology

To determine whether patients with a history of anorexia, bulimia, or bulimia-anorexia differed in terms of personality pathology, we used ANOVA with Scheffé post hoc tests to compare the three groups on axis II diagnoses assessed dimensionally with the SWAP-200. Dimensional personality disorder score were created by correlating subjects’ 200-item Q-sort profiles with composite profiles of prototypic patients with each of the current axis II disorders, which serve as criterion groups (22).

The three groups of patients categorized by lifetime diagnosis (anorexia, bulimia, or bulimia-anorexia) showed few differences, and the differences that did emerge were predictable in light of prior research. The only omnibus F test that was significant was for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (F=5.8, df=2, 94, p=0.004). Post hoc comparisons revealed that patients with anorexia had the highest scores on this variable, followed by patients with bulimia, who in turn had higher scores than patients with a history of both disorders. Grouped instead by current diagnoses (primary or specific), patients with anorexia (or anorexia, restricting type, using the specific current diagnosis) had significantly higher dimensional scores for obsessive-compulsive, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders. In addition, anorexic patients with current or past bulimic symptoms tended to have higher scores for borderline personality disorder than anorexic patients without current or past bulimic symptoms.

Clustering Patients By Personality Styles: Q-Analysis

To identify naturally occurring groupings among eating disorder patients on the basis of personality variables, we used Q-analysis. To cluster patients using Q-analysis, we first entered Q-sort data from all patients into a principal components analysis, specifying eigenvalues ≥1 (Kaiser’s criterion). The scree plot suggested a break after three principal components; the first five cumulatively accounted for 50.2% of the variance. Thus, we subjected the data to three varimax (orthogonal) rotations, specifying three, four, and five factors. All three produced similar solutions with three clear and interpretable factors. On the basis of the coherence of the factors that emerged, we retained the first three factors of the five-factor solution, which cumulatively accounted for 44.4% of the variance. (Retaining three of five factors minimizes “noise” that can occur when the procedure forces items into the last factors.)

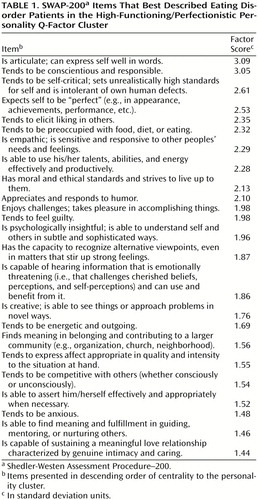

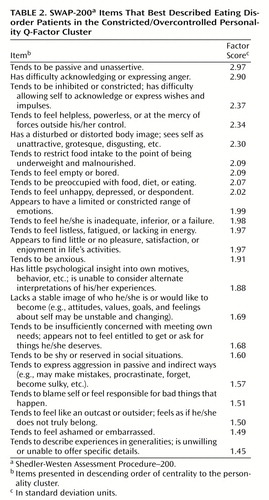

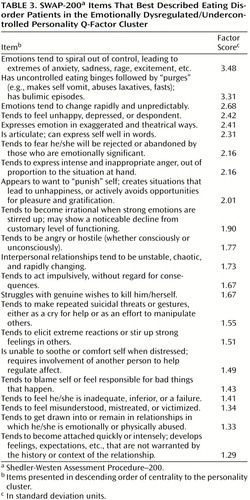

Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3 show the items from the SWAP-200 that best characterized subjects in each Q-factor. The items are arranged in descending order of centrality to the construct; the numbers in the second column are factor scores (in standard deviation units), arranged in descending order of magnitude. These scores provide an index of the extent to which the item is diagnostic of patients in the Q-factor, and are analogous to the factor scores received by subjects in standard factor analysis. For categorical analyses, patients who received factor loading above 0.50 on a cluster (analogous to items with high loadings in r-factor analysis) were considered members of that cluster (and hence received a personality Q-factor diagnosis). Roughly two-thirds of the patients (N=67) had a factor loading above 0.50 on one of the clusters, suggesting that, treated categorically, the three Q-factors captured a substantial percentage of eating disorder patients.

We labeled the clusters high-functioning/perfectionistic, constricted/overcontrolled, and emotionally dysregulated/undercontrolled. Table 1 lists the items that best described the high-functioning/perfectionistic group. Patients in this category are characterized by several healthy attributes, such as conscientiousness and empathy, as well as by a combination of self-criticism, perfectionism, guilt, and anxiety. These women appear to be the “good-girl” eating disorder patients described by a number of authors (see reference 34).

Table 2 lists the items that defined the constricted/overcontrolled group. These patients tend to be much more disturbed than the high-functioning/perfectionistic group. Their constriction extends not only to eating but to a general passivity and inhibition, emotional constriction, constriction of self-awareness and of reflectiveness about the mental processes and behavior of others, and interpersonal constriction and avoidance. These individuals feel like they have nothing inside (“tends to feel empty or bored,” “lacks a stable image of who she would like to become”) and are chronically dysphoric, tending to feel helpless, depressed, inadequate, anhedonic, anxious, and ashamed.

As Table 3 shows, the emotionally dysregulated/undercontrolled group represents an opposite form of pathology: Their emotions are intense, their behaviors are impulsive, they tend to fly into rages instead of expressing their anger passively or turning it inward, and they desperately seek relationships to soothe themselves.

Characteristics of Each Personality Cluster

To develop a more nuanced picture of the three clusters, we examined the relation between each cluster and two sets of variables: axis II pathology and axis I eating disorder diagnosis and symptoms.

Axis II pathology

Because we used the SWAP-200 variables for clustering, it is not surprising that patients classified in each of three clusters showed substantial differences on scores for all 10 axis II personality disorders assessed with this instrument. (Correlational analyses, using the entire study group, rather than only the subjects with a factor loading that qualified them as members of one of the three clusters, produced similar findings.) All group differences were significant at p<0.001 by ANOVA.

Patients in the high-functioning/perfectionistic group had substantially lower scores than the other two groups for all personality disorders assessed with the SWAP-200. The only exception was obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, for which they, like patients in the constricted/overcontrolled group, had higher scores than the patients in the emotionally dysregulated/undercontrolled group. Constricted/overcontrolled patients had higher scores than the other groups for schizoid, schizotypal, and avoidant personality disorders. Patients in the emotionally dysregulated/undercontrolled group had higher scores than the other two groups for paranoid personality disorder, all four cluster B disorders (particularly borderline personality disorder), and dependent personality disorder.

The clinicians’ 7-point personality disorder ratings (ratings of the extent to which the patient met criteria for each axis II personality disorder) were not used in deriving the classification and hence provided appropriate data for inferential statistics. These data told a similar story. The main differences among patients in the three clusters were as follows. For borderline personality disorder, the emotionally dysregulated/constricted group had higher ratings than the other two groups (omnibus F=15.76, df=2, 53, p<0.0001; p<0.001, Scheffé). For antisocial and histrionic personality disorders, the emotionally dysregulated/ constricted group had higher ratings than the other two groups (omnibus F=4.32, df=2, 52, p<0.05; and F=5.49, df=2, 52, p<0.01, respectively; p<0.05, Scheffé, for both). For avoidant personality disorder, in contrast, the constricted/overcontrolled group had significantly higher scores than the high-functioning/perfectionistic group and the emotionally dysregulated group, with Scheffé tests both significant at p<0.05 (one-tailed), although the omnibus F only approached significance (F=2.50, df=2, 52, p=0.09).

Axis I eating disorder diagnosis and symptoms

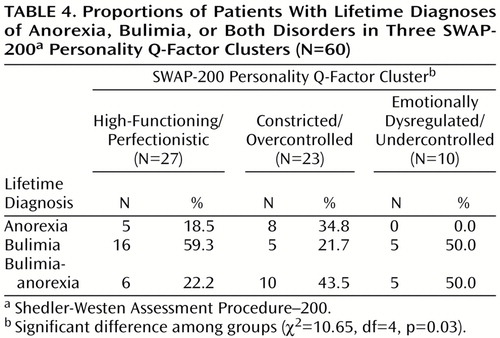

Table 4 shows the proportions of patients with a lifetime diagnosis of anorexia, bulimia, and bulimia-anorexia in each of the three clusters. High-functioning/perfectionistic patients were not aggregated by axis I diagnosis. Relative to the distribution of lifetime diagnoses in the entire study group, patients with bulimia were somewhat overrepresented in this cluster, and patients with bulimia-anorexia were underrepresented. The other two clusters, however, showed substantial differentiation by lifetime eating disorder diagnosis. The vast majority of patients classified as constricted/overcontrolled (78.3%) had anorexic symptoms (a lifetime diagnosis of either anorexia or bulimia-anorexia). In contrast, 100% of patients classified as emotionally dysregulated/undercontrolled had bulimic symptoms (a lifetime diagnosis of either bulimia or bulimia-anorexia); no member of this category had a lifetime history of anorexia only. The proportions of patients with anorexia, bulimia, and bulimia-anorexia in each cluster differed significantly.

Even stronger findings emerged when we crossed cluster membership with specific current axis I diagnosis (anorexia, restricting type; anorexia, binge-eating/purging type; and bulimia). Only 15.8% of subjects in the constricted/overcontrolled cluster received an axis I diagnosis of bulimia, whereas no subject in the emotionally dysregulated/undercontrolled cluster received a diagnosis of anorexia, restricting type (χ2=11.98, df=4, p=0.02).

With respect to specific eating disorder symptoms, we compared the groups on current weight, binge frequency, purge frequency, and presence/absence of compensatory overexercise (coded 0, 1). Because we had specific hypotheses, we used a priori contrasts, testing focal one-tailed hypotheses with one degree of freedom. For current weight, we tested two alternative hypotheses: 1) weight of undercontrolled patients > weight of both high-functioning patients and overcontrolled patients and 2) weight of undercontrolled patients > weight of high-functioning patients > weight of overcontrolled patients. The first hypothesis was more strongly supported (t=1.96, df=57, p=0.03). For binge and purge and overexercise, we tested two hypotheses: 1) frequency in undercontrolled patients > frequency in high-functioning patients > frequency in overcontrolled patients and 2) frequency in undercontrolled patients > frequency in both high-functioning patients and overcontrolled patients. For binge and purge frequencies, the first model was strongly supported (t=2.95, df=56, p=0.003 and t=2.55, df=56, p=0.005, respectively). No differences were found for exercise (t=0.58, df=56, n.s.).

We performed an additional analysis to ascertain whether personality clusters could predict specific eating disorder symptoms above and beyond current axis I diagnosis. Given the relatively strong association between eating disorder diagnosis and cluster scores, this presents a very conservative test of the incremental validity of this empirically generated classification. We used hierarchical multiple regression analysis to predict current body weight (relative to ideal weight), binge frequency, and purge frequency, first entering specific current axis I diagnosis (anorexia, restricting type; anorexia, binge-eating/purging type; and bulimia, each dummy coded 0, 1), and then entering personality Q-scores.

In all three cases, personality Q-scores added significantly to prediction of variance in eating disorder symptoms. For current weight, adding personality Q-scores increased the R2 from 0.23 to 0.35 (multiple R for the complete model=0.59, for a change in F of 5.0, df=3, 83, p=0.003). For binge frequency, adding personality Q-scores to the model increased the R2 from 0.21 to 0.28 (multiple R=0.53, for a change in F of 2.97, df=3, 83, p=0.04). For purge frequency, adding personality Q-scores to the model increased the R2 from 0.15 to 0.24 (multiple R=0.49, for a change in F of 3.3, df=3, 82, p=0.02). In predicting current weight, both overcontrolled and undercontrolled personality Q-scores contributed significantly to prediction, in opposite directions, with overcontrolled scores negatively associated with current weight. In predicting binge frequency, only undercontrolled personality Q-scores contributed significantly (positive beta). In predicting purge frequency, only overcontrolled personality Q-scores were significant predictors (negative beta).

These analyses show that personality variables (personality Q-scores) have incremental validity in predicting eating symptoms (weight, frequency of binge eating, and frequency of purging) above and beyond the categorical diagnoses currently used to describe eating disorder patients on axis I. (Personality variables had an even stronger effect when we entered lifetime diagnosis, rather than specific current axis I diagnosis, as a first step in the hierarchical multiple regression. These findings suggest that personality is a strong predictor of current eating behavior beyond history of eating behavior.

Personality Clusters and Level of Functioning

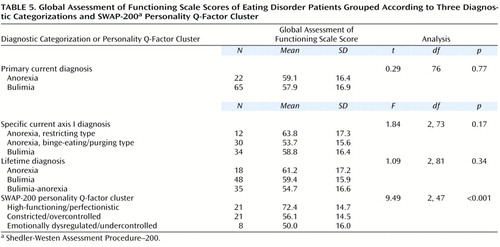

A central question we hoped to address with this study was the extent to which personality profiles would be associated with level of functioning (operationalized as Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores and history of hospitalization) and whether they would be more or less predictive than axis I diagnosis. Because this was a primary aim of the study, we report here both dimensional and categorical analyses.

Axis I diagnosis bore no relation to Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores, either in correlational analyses in which axis I diagnoses were dummy coded 0 or 1 or in categorical analyses using ANOVA (Table 5). In contrast, Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores were strongly and positively correlated with high-functioning/perfectionistic personality Q-scores (r=0.47, df=82, p<0.001) and negatively correlated with emotionally dysregulated/undercontrolled personality Q-scores (r=–0.30, df=82, p=0.006). Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores were uncorrelated with constricted/overcontrolled personality Q-scores (r=–0.16, df=82, n.s.). ANOVA applied to categorical diagnoses for those patients with factor loadings above 0.50 (personality Q-factor diagnoses) produced similar results (F=9.49, df=2, 47, p<0.001).

To compare the three groups in a more focused way, we used contrast analysis, testing two hypotheses specified in advance: 1) the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores of high-functioning patients > those of both overcontrolled patients and undercontrolled patients and 2) the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores of high-functioning patients > those of overcontrolled patients > those of undercontrolled patients. Both contrasts were significant but the first was a slightly better fit (t=4.34, df=36, p<0.001, one-tailed).

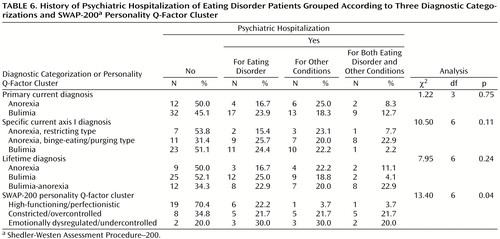

Our second index of level of functioning was history of psychiatric hospitalization, which again bore no significant relation to axis I diagnosis, in either correlational or categorical analyses (Table 6). In contrast, the results of correlational analyses for history of psychiatric hospitalization (coded 0 for never hospitalized and 1 for hospitalized) were similar to those for the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale data: history of psychiatric hospitalization was negatively correlated with high-functioning/perfectionistic personality Q-scores (r=–0.25, df=97, p=0.01) and positively correlated with dysregulated/undercontrolled personality Q-scores (r=0.28, df=97, p=0.005). Constricted/overcontrolled personality Q-scores were not associated with history of hospitalization (r=0.04, df=97, n.s.).

Categorical analysis including only those patients with factor loadings above 0.50 on one of the three Q-factors yielded similar results (Table 6). When we coded psychiatric hospitalization as either never hospitalized or hospitalized, rather than differentiating among types of hospitalizations, as in Table 6, the findings were even stronger for personality Q-factor diagnosis (χ2=11.2, df=2, p<0.005). In contrast, the chi-square value dropped and remained nonsignificant for primary current, current axis I, and lifetime diagnoses.

For more focused analyses, we used contrast analysis, testing two hypotheses specified in advance: 1) psychiatric hospitalization (coded 0 or 1) of high-functioning patients < both overcontrolled patients and undercontrolled patients and 2) psychiatric hospitalization of high-functioning patients < overcontrolled patients < undercontrolled patients. Both contrasts were significant, but the second was a better fit (t=3.41, df=57, p=0.001).

As a final test of the incremental predictive validity of eating disorder personality Q-scores over axis I diagnosis, we conducted two hierarchical multiple regression analyses, one for Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores and one for history of hospitalization. For both, we dummy-coded specific current axis I diagnoses, as above, and entered them first, to see how much of the variance they could explain in level of functioning. As a second step, we added personality pathology cluster scores (personality Q-scores) as predictors.

For Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores, the first model (axis I diagnosis alone) produced an R2=0.05 (F=1.91, df=2, 71, n.s.). The second model, including personality Q-scores, produced an R2=0.30 (multiple R=0.55; for a change in F of 8.16, df=3, 68, p<0.0001). For history of hospitalization (dummy coded 0, 1), the first model produced an R2=0.05 (F=2.2, df=2, 86, n.s.). The second model, including personality Q-scores, yielded an R2=0.13 (multiple R=0.38; for a change in F of 3.23, df=3, 83, p=0.03). In contrast, when we conducted the analyses in the reverse order, first entering personality cluster score and then entering axis I diagnosis, the first model (based on personality Q-scores) produced a strong and highly significant R2, comparable to the second model in both of the analyses just reported. Adding axis I diagnosis led to a nonsignificant R2 change of 0.01 for Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and a nonsignificant R2 change of 0.04 for history of hospitalization. Thus, current axis I diagnosis appears to provide virtually no information in predicting adaptive functioning and severity of disturbance beyond personality Q-factor scores.

Etiology

One of the most important ways of validating a diagnostic grouping is to link it to etiology (35). In this report we focus on one variable selected in advance, sexual abuse, for which potential links to the etiology of eating disorders (e.g., reference 36) and to emotional dysregulation and constriction have been suggested. If the three eating disorder personality dimensions/types are in fact distinct, they should ultimately be associated with different genetic and/or developmental history variables.

We made two alternative a priori hypotheses with respect to presence/absence of a history of sexual abuse, summarized by the following expected size of correlations in dimensional analyses and ordering of groups in categorical analyses: 1) undercontrolled patients > overcontrolled patients > high functioning patients and 2) undercontrolled patients > both overcontrolled patients and high functioning patients. To test these hypotheses, we first correlated presence/absence of history of sexual abuse as reported by the treating clinician (coded 0, 1, excluding cases in which the clinician reported uncertainty) with personality Q-scores for each of the three dimensions (which provides a useful measure of effect size, Pearson’s r). The correlation between the emotionally dysregulated/undercontrolled personality Q-scores and presence of sexual abuse was large and significant (r=0.48, df=67, p<0.0001). The data also revealed a moderate negative correlation between the high-functioning/perfectionistic personality Q-scores and sexual abuse (r=–0.34, df=67, p=0.006). The correlation between the constricted/overcontrolled personality Q-scores and sexual abuse history was not significant (r=0.07, df=67, n.s.). In contrast to these personality cluster scores, no axis I variable representing history or current symptoms showed a significant association with history of sexual abuse.

Next, we treated the data categorically, using personality Q-factor diagnosis as the predictor variable. Although only two-thirds of the patients were classified as members of any cluster (and many clinicians expressed uncertainty about the abuse history of patients for whom the data were unclear, which further decreased the N and hence statistical power to detect group differences), chi-square analysis yielded striking findings. The proportions of patients with a reported history of sexual abuse for the undercontrolled, overcontrolled, and high-functioning groups were 83.3%, 37.5%, and 5.3%, respectively (χ2=14.3, df=2, p<0.001). Comparable analyses predicting sexual abuse history from primary current, specific current axis I, and lifetime diagnoses yielded nonsignificant findings. Finally, we tested our two alternative hypotheses about the ordering of means using contrast analysis applied to frequencies of patients with sexual abuse histories in each group (see reference 33). Both contrasts fit the data, yielding virtually identical t statistics and effect size estimates (t=4.36, df=38, p<0.0001). Although the data are retrospective, they suggest that a history of sexual abuse may be etiologically related to both the emotionally dysregulated/undercontrolled and the constricted/overcontrolled types of eating disorder, particularly the former.

Discussion

Primary Findings

Like previous investigators, we found small but significant group differences in the axis II profiles of patients with current and lifetime axis I eating disorder diagnoses. In general, patients with restricting anorexia tended to be more schizoid and obsessive-compulsive than patients with binge-eating/purging anorexia and patients with bulimia. Patients with both anorexic and bulimic symptoms tended to be slightly more troubled than patients with bulimia alone, particularly with respect to symptoms of borderline personality disorder.

Perhaps more striking, however, was the substantial within-diagnosis heterogeneity that characterized patients with each disorder and the fact that this heterogeneity was not random. Two-thirds of patients in the study group could be assigned one of three categorical diagnoses defined by their personality profiles, which cut across axis I diagnoses, and both dimensional and categorical personality diagnoses could be used to predict axis I symptoms, axis II symptoms, adaptive functioning, and developmental history. Unlike axis I categorization, classification by personality cluster, both categorically and dimensionally, strongly predicted level of functioning, indexed by both Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score and history of psychiatric hospitalization, and sexual abuse, an etiological variable linked in prior research to disordered eating. Despite substantial overlap of cluster membership and axis I diagnosis, cluster scores even predicted unique variance in body mass relative to ideal weight, binge frequency, and purge frequency, after axis I diagnosis was accounted for. (These findings appear to be robust, given that similar clusters, with similar correlates, emerged when we clustered patients by their affect regulation profiles using a different instrument [unpublished 1999 data]. Mapping the two cluster solutions onto one another produced a coefficient of contingency of 0.70, indicating that patients tended to be placed into highly similar clusters by the two instruments.)

The first cluster was a high-functioning/perfectionistic group, who had high Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores, a lower incidence of psychiatric hospitalization, and considerably less personality pathology than the other groups. These patients function well occupationally and interpersonally, although they are chronically self-critical and perfectionistic and tend to feel guilty and anxious. Their pathology appears to be a blend of high-functioning obsessional and depressive features. These are the “good girl” eating disorder patients, whose anorexic and bulimic symptoms may reflect efforts to regulate anxiety, guilt, competition, and problems with self-esteem (see references 12, 34). In this study group, such patients were more likely to be bulimic than anorexic or bulimic-anorexic, although they were not limited to any axis I eating disorder diagnosis.

The data suggest that when eating disorder patients are more troubled, they tend to become disturbed in one of two directions. If they have prominent anorexic symptoms, they are likely to fit a constricted/overcontrolled profile. These patients manifest a constriction and restriction of pleasure, needs, emotions, relationships, self-knowledge, self-reflection, sexuality, and depth of understanding of others that plays out in the domain of food as well. They tend to feel empty or barren inside, are chronically dysphoric, and feel depressed, inadequate, anhedonic, anxious, and ashamed. Their personality pathology tends to be avoidant or schizoid. The more a patient matches this profile, the lower her level of adaptive functioning tends to be. This personality constellation may in some cases reflect in part a characterological adaptation to a history of sexual abuse.

In contrast, when patients with bulimic symptoms (with or without a history of anorexia) are more disturbed, they tend to be emotionally dysregulated, undercontrolled, and impulsive. They experience intense, poorly regulated emotions, and they tend to fly into rages. Rather than fleeing relationships to escape dysphoria (as is the case with the low-functioning anorexic patients), they desperately seek relationships to soothe themselves when they cannot regulate their own emotions. For these patients, eating-disordered symptoms appear to be one more instance of impulsive behavior designed to regulate poorly modulated affects. The data suggest that distinguishing subgroups of bulimic patients on the basis of degree of impulsivity (uni-impulsive versus multi-impulsive [13]) limits the classification to only one aspect of a broader personality structure characterized by emotional dysregulation, intense and labile affect, interpersonal desperation, and impulsive efforts to escape distress and seek gratification. Patients who match this prototype are highly likely to have a sexual abuse history.

These three patterns are not only clinically recognizable, but they also resemble the findings of prior research that used cluster analysis with eating disordered patients (12, 37, 38). Strober (37) applied cluster analysis to the MMPI profiles of patients with anorexia (prior to the current DSM-IV classification of eating disorders) and found three types: a high functioning group who had high levels of conformity and need for control but lacked severe character pathology; an anxious, self-doubting, socially avoidant group; and an impulsive, dysphoric group with low ego strength and poor prognosis. More recently, Goldner et al. (38) applied cluster analytic methods to a self-report measure of personality pathology and found three groups: one with minimal personality pathology that resembled a normal comparison group (but had slightly higher scores relative to this comparison group on a number of scales that did not show any obvious pattern); a second, “rigid” cluster with higher scores on measures of compulsivity and interpersonal difficulties; and a third, essentially borderline, cluster that had higher scores on measures of neuroticism, psychopathy, and behavioral disturbance. Although the mapping of these three systems is not exact, this degree of convergence among cluster-analytic classifications of psychopathology is relatively unusual in psychiatric research, and the obvious convergence of findings from studies relying on different instruments and sampling methods, combined with the data produced here on the validity of this classification (including incremental validity), suggests that these three prototypes are relatively robust.

It is interesting to note that this tripartite classification also resembles the results of Q-analytic studies (see references 30, 39) that have reproduced a personality typology first described by Block (40) in nonclinical subjects. Block distinguished a high functioning, “ego resilient” type; an overcontrolled, constricted type; and an undercontrolled, impulsive type. In the present study, the high-functioning group was more distressed and less resilient than the subjects in Block’s study but was characterized by many similar attributes. Like Block’s three personality patterns, the three patterns described here can be considered as categories of patients or treated as dimensions on which individuals vary.

Limitations and Potential Objections

One could raise several potential objections to this study. The first is the question of reliability of diagnosis, given that structured diagnostic interviews were not used. Three considerations limit this concern. First, the study patients were in treatment for eating disorders and were described by clinicians who had worked with them for an average of 22 sessions and were likely to know their symptoms well. Anorexic and bulimic symptoms are not subtle, and, to the extent that patients are motivated to report honestly about those symptoms (or show them in their body size), they require minimal interpretation. Second, our findings were essentially the same whether we categorized patients on the basis of lifetime history as reported by the clinicians, clinicians’ identification of patients with a current diagnosis of anorexia or bulimia, or DSM-IV diagnoses made by ourselves using data provided by the clinicians, irrespective of the clinicians’ categorical judgments about lifetime history or current diagnosis. Third, our validity checks suggested that patients with a history of or current anorexic symptoms had a much lower body weight relative to ideal body weight and that patients with a history of or current bulimic symptoms had much higher current rates of binge eating and purging. The use of lifetime diagnoses and data provided by clinicians who knew the patients over a substantial time span also limits (although does not eliminate) the potential impact of state-dependent variables on personality assessment. Such variables are particularly problematic for structured interviews, which take a cross-sectional view of the patient, typically on a single day.

A second potential criticism is that the findings primarily reflect clinicians’ intuitive theories or biases, given that the same clinician provided all the data on each patient. Several considerations, however, limit the impact of this feature of the study as well. First, all research relies on observers, and all observers have biases and intuitive theories. Most studies of psychopathology administer self-reports or structured interviews that ask patients to describe themselves and their psychopathology and then examine associations between these self-reported traits or symptoms and other self-reported variables. Our method was no different, except that we used expert informants rather than lay observers for whom lack of insight about themselves is often diagnostic, particularly with respect to personality pathology. Thus, we relied on skilled observers who knew the patients well and used an instrument for which strong correlations between clinicians’ Q-sort descriptions and the Q-sort descriptions of independent judges have been reported (26, 41). We also included criterion variables that required minimal inference, such as history of psychiatric hospitalization and Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores, which show substantial interrater reliability. Future research, however, should use a combination of self-reports, interviews, clinicians’ reports, laboratory measures (such as implicit attentional measures), and reports by significant others.

A second response to the potential concern that we simply documented clinicians’ implicit theories is perhaps more important. Shared theories cannot predict clusters whose existence has not previously been postulated and which predicted variables such as history of psychiatric hospitalization more accurately than the familiar axis I categories. If clinicians’ accounts of their patients’ personality pathology were biased by other judgments they made (such as axis I categorization), the study should have been biased against finding clusters that did not map neatly onto axis I categories. This is equally true of clinicians’ reports of sexual abuse history, which have often been linked in clinical and empirical literature specifically to bulimia, not to subgroups defined by personality variables. In addition, shared theories cannot account for the similarity of our findings whether we used dimensional or categorical measures of personality. Further, the clinicians who provided the data varied substantially by theoretical orientation and professional training and hence did not uniformly share theories that could have produced the observed results.

Finally, previous research suggests that, when asked to describe patients with various diagnoses, clinicians do not in fact tend to reproduce DSM-IV criteria (25, 26). For example, when asked to describe a patient with borderline personality disorder in current treatment by rank-ordering the 200 personality descriptors (including DSM criteria) that constitute the SWAP-200, clinicians did not tend to rank-order the DSM-IV criteria the highest. Rather, they tended to emphasize the patients’ subjective distress more than the socially undesirable traits emphasized in DSM-IV. Other research suggests that clinicians apply appropriate algorithms to determine if a patient’s abuse history is negative, positive, or unclear (25), considering whether the patient began therapy with memories of abuse, was treated in childhood by a physician for injuries related to abuse, and so forth.

Implications

The study results may help explain the inconsistent findings of previous research on the personality characteristics of patients with anorexia and bulimia. Both diagnoses include two subtypes that differ on virtually every psychological dimension, and the extent to which a given study includes subjects with one or the other subtype presumably influences the direction and size of group differences. To what extent these subtypes differ in psychophysiology, prognosis, or treatment response is largely unknown. However, generalizations about bulimic or anorexic patients will likely apply to only a subgroup of patients with each disorder. In future studies, researchers may find it useful to distinguish type I (high-functioning, perfectionistic) and type II (constricted) anorexic patients and type I (high-functioning, perfectionistic) and type II (emotionally dysregulated) bulimic patients. These distinctions do not appear to be captured adequately by the axis I distinction between anorexia, restricting type, and anorexia, binge-eating/purging type. Whether these distinctions map onto the DSM-IV distinction between purging and nonpurging bulimia is unknown, although this seems unlikely.

The findings of this study raise questions about the concept of comorbidity as applied to eating disorders and suggest the likely utility for both research and clinical practice of considering eating-disordered symptoms in their characterological context (e.g., references 12, 34). The data from this study suggest that individuals who develop eating disorders who are constricted in most areas of their lives—e.g., who are passive and unassertive, emotionally constricted, and interpersonally avoidant—are likely to express this pattern with anorexic, rather than bulimic behavior. Clinically, these patients tend to be just as constricted in their sexual lives as they are with food, denying themselves pleasure, avoiding sexual relationships, feeling too ashamed or guilty to indicate to their partners what feels good, and so forth.

Conversely, individuals with eating disorders whose ability to regulate their impulses and affects is tenuous—as expressed in spiraling emotions, tantrums, clinging to others for soothing, self-mutilation, and other impulsive acts—are likely to lose control over their eating in binges and to use self-destructive compensatory measures such as vomiting that momentarily help them regulate their affects. From this point of view, the question of whether bulimic symptoms should be regarded as impulsive behavior may be misplaced. The answer is probably that it depends on the personality configuration within which bulimic symptoms are contextualized. In low-functioning, emotionally dysregulated, type II bulimic patients, binge eating and purging may be functional equivalents of substance abuse, self-mutilation, and promiscuity. For these patients, bulimic symptoms may represent desperate efforts to regulate intense negative affects that call for immediate, and often maladaptive, responses. In contrast, high-functioning, perfectionistic, type I bulimic patients do not struggle with affects of the same intensity, and they have more adaptive coping strategies at their disposal for dealing with their distress. For these patients, binge eating is not equivalent to impulsive behaviors such as drinking or self-mutilation.

More broadly, the data suggest that eating-disordered symptoms can be one expression, albeit a highly visible and sometimes life-threatening one, of a more general pattern of impulse and affect regulation (12). Thus, treating eating disorders primarily as disorders of food intake—and hence focusing primarily on altering the behavior, providing nutritional information (to patients who often know more about calories than the nutritionists who work with them), and so forth—may be taking the symptoms too literally. As in the treatment of trauma survivors (42), safety must be the clinician’s primary concern in treating patients with eating disorders when their symptoms are life-threatening or pose serious consequences for their current or future health. Particularly at those times, pharmacological and cognitive behavioral interventions can be essential components of a treatment plan, as they may be at various other points in the treatment (see reference 43).

At the same time, however, symptom-focused treatment strategies may fail to address the personality structure that provides a context for understanding disordered eating. Patients whose personality profiles match the overcontrolled, constricted prototype, for example, rarely recognize their stance toward their own impulses and relationships as a problem. What brings them into treatment is typically someone else’s concern about their weight. If their attitudes toward their needs and feelings in general (and not just toward food) do not become the object of therapeutic attention, they are likely to change with treatment from being starving, unhappy, isolated, and emotionally constricted people to being relatively well fed, unhappy, isolated, and emotionally constricted people.

The data also raise questions about the extent to which axis II is adequate for describing clinically meaningful patterns of personality pathology, at least for women with eating disorders. Patients in the high-functioning/perfectionistic cluster generally lacked diagnosable axis II pathology; indeed, in our study (as in the other studies that have isolated a similar cluster), they were defined by the absence of such pathology. These patients are articulate, conscientious, and empathic, and they tend to elicit liking in others. Yet they clearly have personality pathology—that is, enduring, problematic patterns of thought, feeling, motivation, and behavior. They are self-critical, perfectionistic, competitive, anxious, and guilt-ridden, and these aspects of their personality require clinical attention. The data reported here make sense in light of other findings that roughly 60% of patients treated for clinically significant personality pathology do not have problems severe enough to be diagnosable on axis II and that their personality problems (e.g., perfectionism and chronic feelings of guilt) generally are not reducible to any axis I syndrome (21, 22). Available data suggest that these patients represent the majority of patients treated in clinical practice and are not simply the “worried well.” Either axis II needs to be expanded from a personality disorderaxis to a personalityaxis that includes the range of functioning (from relatively healthy to relatively impaired), or subtypes such as those uncovered here need to be built into axis I.

From a methodological standpoint, the results of this study suggest that we should routinely test for subtypes in our data sets rather than assuming homogeneity of categories. Group means may not be very meaningful when substantial intracategory heterogeneity exists, particularly if this heterogeneity is ordered, not random. The problem is particularly pronounced if pathology can be expressed in phenotypically opposite directions, leading to means that cancel out patterned within-group variability. Thus, although the etiological data on sexual abuse reported here are correlational and preliminary, they suggest that the same risk factor—sexual abuse—may manifest in opposite personality and behavioral styles—constriction and inhibition on the one hand, and dyscontrol and promiscuity on the other. Whether this is true of other etiologically significant psychosocial variables, such as harsh parental criticism (which, from a clinical point of view, appears sometimes to lead to self-criticism, sometimes to hostility and criticism toward others, and sometimes to both in adulthood), is an important question for future research.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received Sept. 20, 1999; revisions received March 27 and Sept. 8, 2000; accepted Oct. 27, 2000. From the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders, Department of Psychology, Boston University; and RHR International, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. Westen, Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders, Department of Psychology, Boston University, 648 Beacon St., 6th floor, Boston, MA 02215; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Casper R: Personality features of women with good outcome from restricting anorexia nervosa. Psychosom Med 1990; 52:156–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Vitousek K, Manke F: Personality variables and disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol 1994; 103:137–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Skodol A, Oldham J, Hyler SE, Kellman H, Doidge N, Davies M: Comorbidity of DSM-III-R eating disorders and personality disorders. Int J Eat Disord 1993; 14:403–416Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Dolan B, Evans C, Norton K: Disordered eating behavior and attitudes in female and male patients with personality disorders. J Personal Disord 1994; 8:17–27Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Shea MT, Widiger T, Klein MH: Comorbidity of personality disorders and depression: implications for treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:857–868Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lilienfeld SO, Waldman I, Israel AC: A critical examination of the use of the term and concept of comorbidity in psychopathology research. Clin Psychol Sci and Practice 1994; 1:71–83Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Kennedy SH, McVey G, Katz R: Personality disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Psychiatr Res 1990; 24:259–269Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Herzog DB, Keller MB, Lavori PW, Kenny GM, Sacks NR: The prevalence of personality disorders in 210 women with eating disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53:147–152Medline, Google Scholar

9. Steiger H, Liquornik K, Chapman J, Hussain N: Personality and family disturbances in eating-disorder patients: comparison of “restricters” and “bingers” to normal controls. Int J Eat Disord 1991; 10:501–512Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Gartner AF, Marcus RN, Halmi K, Loranger AW: DSM-III-R personality disorders in patients with eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:1585–1591Google Scholar

11. Pryor T, Wiederman MW, McGilley B: Clinical correlates of anorexia nervosa subtypes. Int J Eat Disord 1996; 19:371–379Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sohlberg S, Strober M: Personality in anorexia nervosa: an update and a theoretical integration. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89:1–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lacey JH, Evans CDH: The impulsivist: a multi-impulsive personality disorder. Br J Addict 1986; 81:641–649Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Rief W: Course of multi-impulsive bulimia. Psychosom Med 1994; 24:591–604Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Steinberg S, Tobin D, Johnson C: The role of bulimic behaviors in affect regulation: different functions for different patient subgroups? Int J Eat Disord 1990; 9:51–55Google Scholar

16. Wonderlich SA, Swift WJ: DSM-III-R personality disorders in eating disorder subtypes. Int J Eat Disord 1990; 9:607–616Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Steiger H, Leung F, Thibaudeau J, Houle L, Ghadirian M: Comorbid features in bulimics before and after therapy: are they explained by axis II diagnoses, secondary effects of bulimia, or both? Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34:45–53Google Scholar

18. Dancyger I, Sunday, SR, Eckert ED, Halmi K: A comparative analysis of Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory profiles of anorexia nervosa at hospital admission, discharge, and 10-year follow-up. Compr Psychiatry 1997; 38:185–191Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Herzog W, Schellberg D, Deter HC: First recovery in anorexia nervosa patients in the long-term course: a discrete-time survival analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65:169–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Solhberg S, Norring C: Co-occurrence of ego function change and symptomatic change in bulimia nervosa: a six-year interview-based study. Int J Eat Disord 1995; 18:13–26Medline, Google Scholar