Childhood Abuse and Psychiatric Disorders Among Single and Married Mothers

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the prevalence of, and association between, childhood abuse and psychiatric disorders in single and married mothers. METHOD: Single and married mothers who participated in the Ontario Health Survey, a province-wide study derived from a probability sample of the general population of Ontario aged 15 years and older (N=1,471), were included. Sociodemographic and mental health characteristics were collected by means of interviewer-administered questionnaires. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect information on childhood physical and sexual abuse. RESULTS: Compared with married mothers, single mothers reported substantially lower incomes as well as higher rates of childhood abuse and all psychiatric morbidities examined (current and lifetime affective or anxiety disorders and substance use disorders). Childhood abuse had a consistent and significant association with adult mental health, even when other risk variables were controlled. No interaction among childhood abuse and marital status and outcome was found. CONCLUSIONS: Single mothers reported more childhood abuse and experienced higher levels of poverty and psychiatric disorders than married mothers. Childhood abuse was associated with more psychiatric problems in both single and married mothers. Research, clinical, and policy implications of these findings are discussed.

Single mothers currently head at least 12% of Canadian families with children (1). Studies examining the health of single mothers have demonstrated higher rates of physical and mental health difficulties among single mothers than among mothers in two-parent families (2–5). For example, we found that single mothers were significantly more likely to have mental health problems such as a history of affective disorder, current dissatisfaction with multiple aspects of life, or one or more psychiatric disorders in the past year (2).

Stressors, both past and present, are associated with higher rates of psychiatric problems. Socioeconomic disadvantage is an example of a current stressor that is much more common among single than married mothers (3; unpublished 1993 study by Avison and Thorpe). Past stressors include adverse life events, such as parental death and childhood maltreatment. To our knowledge, no study has examined the relationship among childhood maltreatment, marital status, and psychiatric disorders in a general population sample.

The objective of this study was to examine the relationship between childhood abuse and psychiatric disorders among single and married mothers. To do so, we 1) compared the prevalence of childhood abuse and psychiatric disorders among single and married mothers and 2) examined the association among childhood abuse, marital status, and psychiatric disorders while controlling for other risk variables. We used general population data collected as part of the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey.

Method

Study Sample

Respondents to the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey were a subset of participants from the Ontario Health Survey, a province-wide survey of 61,239 people completed in 1990. The design of the Ontario Health Survey included stratification, clustering, and probability sampling. A detailed review of the survey methodology is described elsewhere (6).

Respondents eligible for the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey were Ontario Health Survey participants in the third and fourth quarters of data collection (7). One respondent was selected from each household. Eligible respondents aged 15–24 years had a chance of being selected that was three times greater than that of eligible respondents 25 years or older in the same household. This oversampling increased the precision of estimates for 15–24-year-olds. As a result, 19.0% of the respondents to the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey were 15–24 years of age, compared with 17.7% of the 1991 Ontario population. Respondents aged 65 years and over were eligible for inclusion if they scored fewer than 11 errors on the standardized Mini-Mental State (8).

The Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey was conducted between December 1990 and April 1991. Almost 10,000 (9,953) people aged 15–98 years participated (76.5% of eligible respondents from the Ontario Health Survey). Reasons for nonparticipation were refusal (N=751); sickness, death, or language difficulties (N=431); failure to contact the household during the survey period (N=744); and unspecified (N=845).

Mothers 15 years and older with at least one dependent child (under 16 years old) were eligible for participation in the study (N=1,540). Only mothers with complete information on all variables available were used in our analysis (N=1,471).

Measures

Measures used included the presence of severe childhood abuse (physical, sexual, or any) and psychiatric disorders (affective or anxiety disorder or substance use disorder in the past year or lifetime). Psychiatric disorders were measured by means of a modified Composite International Diagnostic Interview (9, 10). All data were collected by means of an interviewer-administered questionnaire except the abuse data, which were collected by means of the self-administered Child Maltreatment History Self-Report (11). All variables are defined in Appendix 1.

There were 222 mothers with at least one child under 16 years for which the exact age of the child could not be ascertained. These data are included in a variable defined as “missing young child,” coded as 1 (missing) versus 0 (not missing).

Analysis

We calculated the prevalence rates of childhood abuse, psychiatric disorder, and selected sociodemographic characteristics for single and married mothers and the relative odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to estimate the strength of the association among single mother status and the other variables. The chi-squared statistic was used to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences between single and married mothers.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to determine the strength of the association among childhood abuse, family status, and selected other variables with psychiatric disorder. This was done by forcing all selected independent variables (childhood abuse [any severe abuse], single mother status, income, maternal education, maternal age, young child, and missing young child) into the model and testing for significant interactions between single mother status and the preceding variables to determine which interactions to retain in the model.

To obtain unbiased point estimates, subject responses were weighted by their probability of selection in the sample. The weighting incorporated adjustments for nonresponse to the Ontario Health Survey and the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey and brought the age and sex distribution of the sample into agreement with the distribution of the Ontario population in 1990. SUDAAN (version 7.5, Research Triangle Institute, N.C., 1999) was used for all analyses.

Results

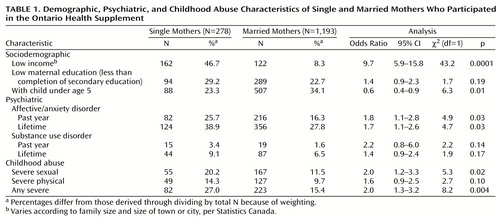

Table 1 provides demographic, psychiatric, and childhood abuse characteristics of the single and married mothers. Single mothers accounted for 18.9% (278 of 1,471) of the sample. The mean ages of the single and married mothers were 36.0 years (SD=10.3) and 36.1 years (SD=12.6), respectively. Almost half of the single mothers were poor compared with less than one-tenth of the married mothers. The prevalence of all psychiatric disorders was higher among single mothers than among married mothers. For example, a lifetime history of affective or anxiety disorder was reported in 38.9% of single mothers and 27.8% of married mothers. The reported rate of any severe childhood abuse among single mothers was almost twice that of married mothers.

Table 2 presents the strength of the association (odds ratios) obtained by means of logistic regression among childhood abuse, single mother status, and selected other variables in predicting lifetime psychiatric disorder. Childhood abuse significantly predicted both psychiatric outcomes and resulted in the largest effect sizes: the odds of a mother who reported childhood abuse experiencing psychiatric morbidity was at least twice that of a mother not reporting childhood abuse. The effect sizes for single mother status were relatively small and nonsignificant. None of the interactions between single mother status and the other tested variables (e.g., abuse) was retained in the model. Additional regressions were performed for psychiatric outcome in the past year. Childhood abuse significantly predicted both psychiatric outcomes (affective or anxiety disorder: odds ratio=2.49, χ2=15.81, df=1, p=0.0001; substance use disorder: odds ratio=6.18, χ2=7.77, df=1, p=0.01). Single mother status did not significantly predict either psychiatric outcome in the past year: affective or anxiety disorder, odds ratio=1.53, χ2=2.99, df=1, p=0.08; substance use disorder, odds ratio=1.32, χ2=0.23, df=1, p=0.63. No other main effects or interactions significantly predicted outcome.

Discussion

Comparisons between single and married mothers in a large general population sample from Ontario consistently revealed that single mothers reported a higher prevalence of severe childhood abuse than married mothers. The odds of a single mother reporting severe childhood sexual abuse, or any severe childhood abuse, was twice that of married mothers. Single mothers also had higher rates of all psychiatric disorders examined and lower incomes.

Logistic regression analysis revealed that reported childhood abuse was a strong and significant predictor of maternal psychiatric morbidity, even after controlling for other risk variables (family composition, maternal age, and sociodemographic variables). The effect sizes of single mother status on outcome were nonsignificant, and no significant interactions were found between single mother status and other variables, such as childhood abuse, for psychiatric outcomes.

Two cross-sectional studies performed with disadvantaged populations both found a higher prevalence of childhood maltreatment among single mothers than among married mothers (12, 13). In the study of 404 inner-city British women, the authors stated that both single mother status and childhood maltreatment predicted comorbid depression and anxiety disorders, but no specific estimates were provided (12). The Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey was the first survey to examine the rate of childhood abuse among single mothers in the general population.

Higher levels of reported childhood abuse and psychiatric disorders among single mothers led us to test for an interaction between single mother status and childhood abuse in the prediction of psychiatric outcomes. The theoretical basis for this test is the hypothesis that exposure to childhood abuse creates an early vulnerability to psychiatric difficulties that is activated by periods of interpersonal stress (e.g., at marital dissolution). Conversely, the absence of such stress (e.g., maintenance of an intact family) attenuates some of the negative effects associated with exposure to childhood abuse. This study does not support a differential effect of childhood abuse on single mothers compared with married mothers in predicting psychiatric disorders.

Comparisons of difficulties among single and married mothers must be interpreted cautiously. The tradition of comparing single mothers with mothers from potentially less stressed groups may be seen as perpetuating negative stereotypes about single mothers (14, 15). There is considerable heterogeneity among single mothers (2), and there are likely marked individual differences in how they cope (16). In the current study, single and married mothers both showed difficulties associated with childhood abuse. The similarities between these two groups of mothers are as important as the differences.

Strengths of the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey include rigorous methodology and sophisticated sampling techniques to ensure a group representative of the general population, a large sample size, and poststratification weighting to minimize bias associated with the loss of participants.

Limitations include the inability to establish the chronology of experiences such as childhood abuse and psychiatric problems in a cross-sectional study. Also, the sampling strategy used in the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey focused on household dwellings, excluding specific groups (homeless people or native people living on reserves) who might have been at a higher risk for both childhood abuse and single parenthood (17–19). Since these groups represent a small proportion of the total population of Ontario (20), their exclusion is unlikely to have a large impact.

Possible biases associated with retrospective self-reports of childhood abuse (21–25) must be acknowledged. However, there is no reason to suggest that a selective difference in recall exists between single and married mothers (26). It is unlikely that recall bias could account for the finding that single mothers reported a greater prevalence of childhood abuse than did married mothers.

Results of this study have implications for the research, clinical, and policy fields. Researchers must endeavor to further understand the mechanisms through which childhood abuse influences adult mental health. Clinicians should be cognizant of the high prevalence of childhood abuse among single mothers. Routine assessments of mothers with psychiatric difficulties, particularly single mothers, should include questions about childhood abuse. Treatment of psychiatric conditions such as depression may be influenced by a history of childhood abuse (27). Finally, these findings should encourage policy makers to make interventions for childhood maltreatment a priority. These data suggest that decreasing childhood abuse can potentially have a long-term influence on reducing the prevalence of adult psychiatric disorders, such as mood disorders, and the associated burden of suffering.

In conclusion, single mothers reported higher rates of childhood abuse than did married mothers. A strong and significant association exists between childhood abuse and psychiatric difficulties for both single and married mothers, even when maternal age, family composition, and sociodemographic disadvantages are controlled. No interaction between single mother status and childhood abuse was found for psychiatric outcomes. The mechanisms through which childhood abuse influences adult mental health are yet to be determined. This problem deserves further study in both single and married mothers.

|

|

Presented in part at the 151st annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Toronto, Ontario, May 30–June 4, 1998. Received Aug. 21, 1998; revisions received June 1, 1999, and March 13 and July 7, 2000; accepted Aug. 4, 2000. From the Canadian Centre for Studies of Children at Risk, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lipman, Centre for Studies of Children at Risk, McMaster University and Hamilton Health Sciences Corporation, Chedoke Campus, Patterson Bldg., P.O. Box 2000, Hamilton, Ontario, L8N 3Z5 Canada; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by an Intermediate Research Fellowship from the Ontario Mental Health Foundation (Dr. Lipman), a W.T. Grant Foundation Faculty Scholar Award and the Wyeth-Ayerst Canada Inc. and Medical Research Council of Canada Clinical Research Chair in Women’s Mental Health (Dr. MacMillan), and a Scientist Award from the Medical Research Council of Canada (Dr. Boyle). The authors thank Maria Wong and Eric Duku for computing assistance and Jim Julian for statistical advice.

|

APPENDIX 1.

1. 1996 Census Nation Table. Ottawa, Statistics Canada, 1996Google Scholar

2. Lipman EL, Offord DR, Boyle MH: Single mothers in Ontario: sociodemographic, physical and mental health characteristics. Can Med Assoc J 1997; 156:639–645Google Scholar

3. Weissman M, Leaf P, Bruce JL: Single parent women. Soc Psychiatry 1987; 22:29–36Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Beatson-Hird P, Yuen P, Balarjan R: Single mothers: their health and health service use. J Epidemiol Community Health 1989; 43:385–390Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wolfe BL, Hill S: The Health, Earnings Capacity, and Poverty of Single-Mother Families: Discussion Paper 964-92. Madison, Wis, Institute for Research on Policy, 1992Google Scholar

6. Documentation: Volume 1 of Ontario Health Survey 1990: User’s Guide. Toronto, Ontario Ministry of Health, 1990, pp 25–50Google Scholar

7. Boyle MH, Offord DR, Campbell D, Catlin G, Goering P, Lin E, Racine YA: Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey: methodology. Can J Psychiatry 1996; 41:549–558Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, Sartorius N, Towle LH: The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1069–1077Google Scholar

10. Essau CA, Wittchen H-U: An overview of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods in Psychiatr Res 1993; 3:79–85Google Scholar

11. MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Trocme N, Boyle MH, Wong M, Racine YA, Beardslee WR, Offord DR: Prevalence of child physical and sexual abuse in the community: results from the Ontario Health Supplement. JAMA 1997; 278:131–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Brown GW, Moran PM: Single mothers, poverty and depression. Psychol Med 1997; 27:21–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Olson SL, Kieschnick E, Banyard V, Ceballo R: Socioenvironmental and individual correlates of psychological adjustment in low income single mothers. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1994; 64:317–331Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Blechman E: Are children with one parent at risk? a methodological critique. Marriage and Family 1982; 44:179–195Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Sprey J: The study of single parenthood: some methodology and considerations. Family Coordinator 1967; 16:29–34Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Brown GW, Harris TO: Social Origins of Depression: A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. London, Tavistock, 1978Google Scholar

17. Kufeldt K, Nimmo M: Youth on the street: abuse and neglect in the eighties. Child Abuse Negl 1987; 11:531–543Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Windle M, Windle RC, Scheidt DM, Miller GB: Physical and sexual abuse and associated mental disorders among alcoholic inpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1322–1328Google Scholar

19. Statistics Canada: Language, Tradition, Health, Lifestyle and Social Issues, 1991: Aboriginal Peoples Survey: Catalogue Number 89-533. Ottawa, Minister of Industry, Science and Technology, 1993Google Scholar

20. Profile of Canada’s Aboriginal Population: Catalogue Number 94-325. Ottawa, Statistics Canada, 1995Google Scholar

21. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Gotlib IH: Psychopathology and early experience: a reappraisal of retrospective reports. Psychol Bull 1993; 113:82–98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Widom CS, Shepard RL: Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization, part 1: childhood physical abuse. Psychol Assess 1996; 8:412–421Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Williams LM: Recall of childhood trauma: a prospective study of women’s memories of child sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:1167–1176Google Scholar

24. Femina DD, Yeager CA, Lewis DO: Child abuse: adolescent records vs adult recall. Child Abuse Negl 1990; 14:227–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Bodkin A, Oliva P: Questionable validity of “dissociative amnesia” in trauma victims. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172:210–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Fiscella K, Kitzman HJ, Cole RE, Sidora KJ, Olds D: Does child abuse predict adolescent pregnancy? Pediatrics 1998; 101:620–624Google Scholar

27. Downey G, Feldman S, Khuri J, Friedman S: Maltreatment and childhood depression, in Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. Edited by Reynolds WM, Johnston HF. New York, Plenum Press, 1994, pp 481–508Google Scholar

28. 1989 Poverty Lines: Estimates by the National Council of Welfare. Ottawa, National Council on Welfare, 1989Google Scholar

29. Income distributions by Size in Canada, 1989. Ottawa, Statistics Canada, 1990Google Scholar