The Patient-Provider Relationship: Attachment Theory and Adherence to Treatment in Diabetes

Abstract

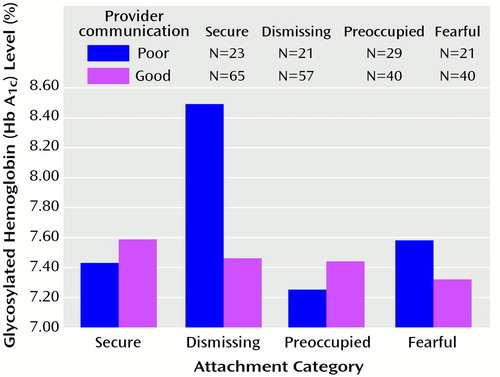

OBJECTIVE: Lack of adherence to diabetic self-management regimens is associated with a high risk of diabetes complications. Previous research has shown that the quality of the patient-provider relationship is associated with adherence to diabetes treatment. This study attempts to improve understanding of both patient and provider factors involved in lack of adherence to treatment in diabetic patients by using the conceptual model of attachment theory. METHOD: Instruments that assessed attachment, treatment adherence, depression, diabetes severity, patient-provider communication, and demographic data were administered to 367 patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes in a health maintenance organization primary care setting. Glucose control, medical comorbidity, and adherence to medications and clinic appointments were determined from automated data. Analyses of covariance were used to determine if attachment style and quality of patient-provider communication were associated with adherence to treatment. RESULTS: Patients who exhibited dismissing attachment had significantly worse glucose control than patients with preoccupied or secure attachment. An interaction between attachment and communication quality was significantly associated with glycosylated hemoglobin (Hb A1c) levels. Among the patients with a dismissing attachment style, there was a significant difference in glycosylated hemoglobin levels between those who rated their patient-provider communication as poor (mean=8.50%, SD=1.55%) and those who rated this communication as good (mean=7.49%, SD=1.33%). Among all patients who were taking oral hypoglycemics, adherence to medications and glucose monitoring was significantly worse in patients who exhibited dismissing attachment and rated their patient-provider communication as poor. CONCLUSIONS: Dismissing attachment in the setting of poor patient-provider communication is associated with poorer treatment adherence in patients with diabetes.

Diabetes mellitus is a common and costly chronic medical illness that affects more than 16 million Americans (1). Individuals with diabetes are at greater risk of long-term complications such as kidney disease, peripheral vascular disease, lower extremity ulcers and amputations, retinopathy, and neuropathy. Diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States, and the total direct and indirect costs in the United States due to diabetes mellitus have been estimated at $102 billion per year (2). Diabetes is considered one of the most psychologically and behaviorally demanding of the chronic medical illnesses (3), and 95% of diabetes management is conducted by the patient (4).

For patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, studies have emphasized the importance of achieving optimal glucose control through strict adherence to medications, diet, and exercise in order to minimize serious long-term complications (5, 6). It is increasingly being recognized that a collaborative relationship between patient and provider may improve patient adherence and outcomes in chronic medical illnesses (7–9). Researchers have shown that satisfaction with the interpersonal quality of the patient-provider relationship is significantly associated with adherence to treatment in diabetes (10). Translating this knowledge into improved clinical practice has been a challenge, since researchers are still struggling to determine specific patient and provider factors that may be associated with a positive therapeutic alliance and treatment adherence in medical care.

We hypothesized that a patient’s satisfaction and participation in the patient-provider relationship can be understood by using the construct of adult attachment theory. John Bowlby, who first developed attachment theory, proposed that individuals internalize earlier experiences with caregivers and form cognitive models that determine for the individual whether they are worthy of care (view of self) and whether others can be trusted to provide care (view of others). These cognitive models or “internal working models” influence the kinds of interactions individuals have with others and their interpretations of these interactions throughout the life cycle (11). From empirical research in infants, children, and adults, attachment researchers have determined that there are four main categories of attachment in adults: secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful (12).

Adults with secure attachment likely experienced consistently responsive early caregiving (13); they are comfortable depending on, and are readily comforted by, others (positive view of self and others). Adults with dismissing attachment are believed to have experienced early caregiving that was consistently emotionally unresponsive, and as a result they develop strategies in which they become “compulsively self-reliant” (positive view of self) but are uncomfortable being close to or trusting others (negative view of others) (14). On the other hand, adults with preoccupied attachment likely experienced caregiving that was inconsistently responsive (15). As a consequence, they become excessively vigilant of attachment relationships and emotionally dependent on the approval of others (positive view of others)—often to the point of being “clingy”—but generally have poor self-esteem (negative view of self). Fearful individuals share many of the characteristics of preoccupied individuals in that they desire social contact, but this desire is inhibited by fear of rejection. These individuals are proposed to have had overly critical or harsh rejecting caregiving (negative view of self and others). As adults they are more likely to demonstrate interpersonal patterns in which they flee once a certain level of closeness is attained, i.e., engage in approach-avoidance behavior patterns that stem from a fear of intimacy (16).

We posited that the compulsive self-reliance that characterizes individuals who exhibit dismissing attachment is largely incompatible with the collaborative working relationship between patient and provider that has been shown to be increasingly important in patients with chronic illness (9). In the current study, we hypothesized that patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes who exhibit dismissing attachment would have significantly worse adherence to treatment as indicated by glucose control than would diabetic patients with other attachment styles. Because some providers may naturally adjust to the inflexibility displayed by a patient with a dismissing attachment style in order to optimize the patient’s participation in the health care relationship, we also hypothesized that provider factors may, in part, modify this association. We posited that in the absence of good patient-provider communication, adherence to treatment in patients who exhibit dismissing attachment would be significantly worse.

Method

This study took place in two primary care clinics of Group Health Cooperative, a large staff-model health maintenance organization (HMO) in Puget Sound, Wa. The two clinics were staffed by 22 board-certified family physicians. Group Health Cooperative has developed a diabetes improvement program, the primary feature of which is an automated diabetes registry that tracks diabetic patients and includes demographic, pharmacy, laboratory, and utilization data. All English-speaking patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes who were over 18 years of age and were enrolled at the two primary care clinics for at least 2 years were eligible to participate in the study. Furthermore, eligible patients were required to have had at least three visits with the same primary care physician during the 2 years preceding the study to ensure familiarity between patient and provider for the purposes of completing patient self-report evaluations of providers. Patients with severe cognitive or language deficits were excluded from the study. In November 1998, all 588 eligible patients with diabetes in the two clinics were sent a letter that described the study and offered the option of declining further involvement. Two weeks later, participating subjects were sent a questionnaire, a request for consent to obtain registry data, and a compensation of $10 for their time in filling out the questionnaire. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Mailed reminders were sent 2 and 4 weeks after the initial questionnaire to patients who had not yet responded.

Measures

Patients filled out seven self-report instruments. Two questionnaires determined the attachment style of the respondents: the Relationship Scales Questionnaire (17), a valid and reliable 30-item instrument, and the Relationship Questionnaire (17), for which subjects read paragraphs describing the four different attachment categories and rated how well the paragraphs described them on a 7-point Likert scale. Results from these two questionnaires were combined by averaging z-transformed data, from which a categorical attachment style was determined for each subject on the basis of the attachment category with the highest score (18).

The Patient Reactions Assessment (19) assessed affective and informative behaviors of the provider and the quality of communication with the provider. This instrument and its subscales demonstrated high internal consistency and concurrent validity in its ability to differentiate known groups of providers with respect to quality of patient-provider relationships. The communication subscale, used in this study, measures the patients’ perceived ability to initiate communication about the illness with their specific provider (e.g., “It is hard for me to tell the person about new symptoms”). We dichotomized the 7-point Likert scale responses into “good communication” (i.e., very strongly disagree, strongly disagree, and disagree) and “poor communication” (i.e., unsure, agree, strongly agree, and very strongly agree).

The 20 items from the depression and additional symptom subscales of the SCL-90-R (20), a self-report instrument that has been validated in previous studies of medical patients and has been found to be highly reliable, were used in the current study.

The presence of diabetes complications was determined from a self-report checklist of complications in order to measure diabetes severity. Patients were given a score from 0 to 3 that was based on their total out of three principal diabetes complications: retinopathy, nephropathy, and peripheral neuropathy (21).

The Diabetes Knowledge Assessment scale (22), a valid and reliable 15-item instrument, assessed patient knowledge about diabetes and its treatment. Form A was used in this study, and scores were expressed as a percentage of correct answers. Finally, the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Questionnaire (23), a 12-item instrument shown to be a valid and reliable measure of diabetes self-management in multiple trials, measured both absolute levels of self-care behavior and percentage of these activities recommended by the doctor that were actually performed. In this study, diet amount, diet type, exercise, and glucose monitoring were assessed; since items within each domain have different scales, raw scores for each were converted to standard scores having a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Standardized scores were averaged to form a composite z score for each regimen behavior. A higher z score indicated better adherence to the self-care behavior.

Demographic and clinical data were determined both from questionnaire responses (race, education, and marital status) and from automated data (age, gender, and type of diabetes treatment). We also used automated data to determine the following clinical variables. Mean glycosylated hemoglobin (Hb A1c) levels were obtained for each subject for the preceding 8 months. The Group Health Cooperative laboratory uses a BM/Hitachi 917 immuno-inhibition assay (Roche-Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) to analyze glycosylated hemoglobin.

Ratings of chronic medical comorbidity were obtained by means of the Chronic Disease Score, an index based on automated pharmacy data of medications used to treat chronic medical conditions. The Chronic Disease Score has been shown to correlate with physician ratings of physical disease severity and to predict mortality and hospital utilization (24). Diabetes medications were excluded in determination of the Chronic Disease Score in this study.

A measure of nonadherence to treatment was made by determining interruptions of treatment for the 236 patients (64.3%) who were on a regimen of oral hypoglycemics. Following the methods of Unützer et al. (25), we defined an interruption as a case in which a refill or subsequent prescription of oral hypoglycemics was overdue by more than 14 days. For each subject, we calculated the percentage of days in interruption by summing all days in interruption and dividing by the total number of days in treatment with oral hypoglycemic medications over a 15-month period.

Assessment of primary care utilization for the past year was determined by using data from the Group Health Cooperative utilization and cost system and was limited to primary care outpatient utilization.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 8.0 for Windows (Chicago). Two-tailed t tests or chi-square tests with corrections for continuity were used to compare respondents and nonrespondents on age, gender, glycosylated hemoglobin levels, and Chronic Disease Score, after appropriate human subjects approval to obtain means and standard deviations or percentages on aggregate data of nonrespondents on these variables.

Demographic and clinical variables in respondents were compared between 1) attachment groups, by means of analyses of variance or chi-square tests with corrections for continuity, and 2) patient-rated quality of patient-provider communication, by means of two-tailed t tests or chi-square tests.

Analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were performed in order to determine if glycosylated hemoglobin levels varied as a function of attachment style (secure, dismissing, preoccupied, or fearful) and communication quality (poor or good). Potential covariates included age, age at diabetes onset, gender, education, severity of depression, severity of diabetes, type of diabetes treatment, medical comorbidity, race, and diabetes knowledge.

In the event of a significant interaction or main effect involving attachment style, post hoc analyses were conducted by using ANCOVAs to determine which group differences in adherence to treatment demonstrated significant differences in glycosylated hemoglobin levels. These analyses adjusted for relevant covariates. Exploratory ANCOVAs were also performed to determine the presence of group differences in the following domains of adherence: diet amount, diet type, exercise, glucose monitoring, adherence to oral hypoglycemics, and primary care utilization.

Results

Of the 588 subjects who received questionnaires, 367 (62.4%) returned questionnaires and consented to the release of their automated data. Respondents and nonrespondents did not significantly differ in age, gender, glycosylated hemoglobin levels, or Chronic Disease Score.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of respondents by communication quality are shown in Table 1. The groups significantly differed in terms of diabetes knowledge, gender, race, education, and presence of depressive symptoms. Demographic and clinical characteristics of respondents by attachment category are shown in Table 2. The groups significantly differed in terms of age, age at diabetes onset, gender, education, presence of depressive symptoms, and in the number of patients whose treatment regimen included insulin and hypoglycemics. The preceding variables were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

There was a significant effect of attachment style on glycosylated hemoglobin level (F=3.02, df=3, 292, p=0.03). Post hoc tests revealed that patients who exhibited dismissing attachment had significantly higher glycosylated hemoglobin levels (mean=7.99%, SD=1.49%) than did patients with preoccupied (mean=7.38%, SD=1.23%), secure (mean=7.49%, SD=1.24%), and fearful (mean=7.47%, SD=1.32%) attachment styles (p=0.05, Tukey’s honestly significant difference). Communication quality did not show a significant main effect (F=2.69, df=1, 294, p<0.11). However, the interaction between attachment category and patient-rated quality of provider communication was significantly associated with glycosylated hemoglobin levels (F=2.74, df=3, 292, p<0.05) (Figure 1). The interaction was due to the observation that patients who exhibited dismissing attachment and perceived that the quality of communication with their provider was poor had higher glycosylated hemoglobin levels (mean=8.50%, SD=1.55%) than did those with a dismissing attachment style who perceived their provider’s communication as good (mean=7.49%, SD=1.33%) (F=4.32, df=1, 76, p<0.05). There were no significant differences in glycosylated hemoglobin levels by communication quality in the patients with secure, preoccupied, or fearful attachment styles. The interaction was not the result of significantly different proportions of patients in different attachment groups rating communication with providers as poor (Table 2). Furthermore, we derived aggregate communication scores for each of the 22 providers to establish whether providers for patients who exhibited dismissing attachment and rated their provider’s communication as poor were perceived by their overall panel of study diabetic patients as having significantly worse communication than providers for all other patients. Providers for the dismissing/poor provider communication group were not perceived by their overall panel of diabetic patients as having poorer communication on the Patient Reactions Assessment scale than other providers (mean=5.36, SD=0.25, versus mean=5.35, SD=0.24, respectively; t=0.15, df=351, p<0.88).

We analyzed the subgroup of patients treated with oral hypoglycemics, comparing patients who exhibited dismissing attachment and rated their provider’s communication as poor with all other patients on several self-report measures and automated indices of adherence. The dismissing/poor provider communication group had significantly worse adherence to glucose monitoring and had a significantly greater number of interruptions in treatment with oral hypoglycemics (Table 3).

Discussion

In a large group of patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes in a staff-model primary care HMO, we found after adjusting for demographic and clinical variables that patients who exhibited dismissing attachment had significantly higher glycosylated hemoglobin levels than did patients with secure and preoccupied attachment styles. When we accounted for the quality of patient-provider communication, the magnitude of this association was even greater among patients with dismissing attachment: those who assessed communication with their provider as poor had glycosylated hemoglobin values 1.01% higher than those who assessed their patient-provider communication as good. We explored possible mechanisms resulting in higher glycosylated hemoglobin levels among all patients treated with oral hypoglycemics and found that patients who exhibited dismissing attachment and rated their provider’s communication as poor had significantly poorer adherence to glucose monitoring and significantly more interruptions in treatment with oral hypoglycemics than the remainder of the study patients.

This study has several limitations. It was cross-sectional in design, and the causal relationship between glycosylated hemoglobin levels and attachment style or between glycosylated hemoglobin levels and quality of communication cannot be definitively determined. With regard to attachment, however, attachment style is a relatively stable trait; it is unlikely that nonadherence to diabetes treatment alters attachment style. With regard to the patient-provider relationship, it is possible that the quality of patient-provider communication was influenced by patient nonadherence to treatment, e.g., provider frustration with poor patient treatment adherence may adversely influence communication within the relationship. We have planned a longitudinal follow-up of patients in this study with a data collection 12 months after baseline measurements to help improve our understanding of causality.

Another limitation of this study is the potential lack of generalizability of this predominantly white, educated, employed, and insured HMO population to other settings. Particularly at issue here may be the smaller degree of socioeconomic barriers to treatment in this group than would be seen in a truly representative national sample.

Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility of selection bias resulting from the characteristics of the clinical group of focus in this study. For example, it is conceivable that patients who exhibit dismissing attachment and have poorer adherence to diabetes self-care (and higher glycosylated hemoglobin levels) may also be less likely to adhere to a study questionnaire. Alternatively, it is possible that such patients, who also find themselves in a poor patient-provider relationship, may be more inclined to respond to a questionnaire that targets, among other things, the quality of their provider’s communication.

This study has several strengths. First of all, we obtained naturalistic data in a large HMO primary care population, which is likely more generalizable than had this study been done in a tertiary care setting. Second, we were able to make extensive use of automated data to obtain objective measures of adherence (e.g., glycosylated hemoglobin levels, pharmacy adherence data, and utilization data). The strength of adherence studies is increased when objective measures are used and particularly if multiple measures can be used (26).

Attachment theory is a theory of interpersonal relationships that proposes that the quality of early caregiving influences how an individual perceives and engages in subsequent relationships. We believe that this applies to the health care relationship. Individuals with a dismissing attachment style develop a pervasive need for independence and self-sufficiency because of caregiving that had very often been unresponsive or even neglectful. These characteristics that were perhaps adaptive in earlier relationships persist into adulthood and into health care relationships, which makes the likelihood of a sustained working relationship with health care providers less likely. Thus, glucose control would be predicted to be worse in diabetic patients who exhibit dismissing attachment, as was shown in this study. Other research groups have shown that a dismissing attachment style is associated with fewer visits to health professionals (27), greater rejection of treatment providers, less self-disclosure, and worse use of treatment (28).

Previous studies have shown that patient satisfaction with the patient-provider relationship is associated with improved adherence to treatment in diabetic patients. It is conceivable that the influence of this association on adherence is exaggerated in patients with a dismissing attachment style. In the current study, we found that among patients who perceived the quality of patient-provider communication as poor, those patients with a dismissing attachment style were likely to be far more disengaged from their providers and thus less adherent to treatment, as indicated by higher glycosylated hemoglobin values.

The clinical significance of a 1.01% higher glycosylated hemoglobin level in the patients who exhibited dismissing attachment and rated their provider’s communication as poor is demonstrated by research showing that over a 10-year period, a 1% increase in glycosylated hemoglobin level at baseline was associated with nearly a 60% increase in the incidence of retinopathy (29). The relevance of this is even more significant from a population-based perspective when one considers individuals with dismissing attachment styles make up 25% of the general population, as was shown in the National Comorbidity Survey (30) (we found a similar proportion in the current study population). It is conceivable that clinical use of a short attachment measure would allow clinicians to readily identify the sizable proportion of patients with problematic adherence to treatment that have a dismissing attachment style. This is a clinical group in which particular emphasis may need to be placed on the patient-provider relationship. Subsequent studies are required to identify the quality and dynamics of the dyad between provider and the patient with a dismissing attachment style. In our study, over 70% of the patients who exhibited dismissing attachment rated communication with their providers as good. Very likely, providers of these patients have an ability to compensate for the inflexibility displayed by individuals with a dismissing attachment style and develop a sustained working relationship with these patients. We are currently collecting data to determine practice characteristics and attachment style of the health care providers involved in this study.

In summary, patients who exhibited dismissing attachment and perceived their patient-provider communication as poor had significantly higher glycosylated hemoglobin levels than patients with other attachment styles regardless of the quality of the patient-provider communication. The significant differences between these groups in medication adherence and glucose monitoring potentially indicates a disengagement from treatment by patients who exhibit dismissing attachment, particularly in the absence of good patient-provider communication. Jacobson and colleagues (31) emphasized the need for further research on nonadherence in diabetes with a particular focus on the patient-provider relationship. We are hopeful that this current line of research will lead to better interventions in dealing with nonadherence in diabetes and other medical and mental illnesses.

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 57th annual scientific meeting of the American Psychosomatic Society, Vancouver, B.C., Canada, March 17–20, 1999, and at the APA Research Colloquium for Junior Investigators, NIH, Bethesda, Md., May 16, 1999. Received Sept. 13, 1999; revisions received March 28 and July 14, 2000; accepted July 27, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington; and the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Seattle. Address reprint requests to Dr. Ciechanowski, Box 356560, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the Group Health Cooperative/Kaiser Permanente Community Foundation and the Bayer Institute for Health Care Communication. The authors thank Edward H. Wagner, M.D., M.P.H.; Irl Hirsch, M.D.; David McCullough, M.D.; and Gregory E. Simon, M.D., M.P.H., for scientific input and the members of the Center for Health Studies at Group Health Cooperative for support in carrying out the study.

Figure 1. Glycosylated Hemoglobin Levels of Patients With Type 1 or 2 Diabetes in Relation to Attachment Category and Patient-Rated Quality of Provider Communication

1. Diabetes in America. Washington, DC, National Institutes of Health, 1995Google Scholar

2. Direct and Indirect Costs of Diabetes in the United States in 1992. Alexandria, Va, American Diabetes Association, 1992Google Scholar

3. Cox DJ, Gonder-Frederick L: Major developments in behavioural diabetes research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:628–638Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Anderson RM: Is the problem of compliance all in our heads? Diabetes Educ 1985; 11:31–34Google Scholar

5. DCCT Research Group: Influence of intensive diabetes treatment on quality of life outcomes in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care 1996; 19:195–203Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group: Intensive blood-glucose control with sulfonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352:837–853; correction, 1999; 354:602Google Scholar

7. Roter D, Hall JA: Doctors Talking With Patients/Patients Talking With Doctors: Improving Communication in Medical Visits. Westport, Conn, Auburn House, 1992, p 203Google Scholar

8. Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE Jr: Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care 1989; 27:S110–S127; correction, 27:679Google Scholar

9. Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH: Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127:1097–1102Google Scholar

10. Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Ordway L, DiMatteo MR, Kravitz RL: Antecedents of adherence to medical recommendations: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. J Behav Med 1992; 15:447–468Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Bowlby J: Attachment and Loss, vol II: Separation: Anxiety and Anger. New York, Basic Books, 1973Google Scholar

12. Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM: Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol 1991; 61:226–244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Ainsworth MS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S: Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1978Google Scholar

14. Bowlby J: The making and breaking of affectional bonds. Br J Psychiatry 1977; 130:201–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bartholomew K: Avoidance of intimacy: an attachment perspective. J Social and Personal Relationships 1990; 7:147–178Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Bartholomew K: From childhood to adult relationships: attachment theory and research, in Learning About Relationships: Understanding Relationships Processes Series, vol 2. Edited by Duck S. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1993, pp 30–62Google Scholar

17. Griffin DW, Bartholomew K: The metaphysics of measurement: the case of adult attachment. Advances in Personal Relationships 1994; 5:17–52Google Scholar

18. Ognibene TC, Collins NL: Adult attachment styles, perceived social support and coping strategies. J Social and Personal Relationships 1998; 15:323–345Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Galassi JP, Schanberg R, Ware W: The Patient Reactions Assessment: a brief measure of the quality of the patient-provider medical relationship. Psychol Assess 1992; 4:346–351Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Derogatis LR: SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual, 3rd ed. Towson, Md, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1994Google Scholar

21. Jacobson AM, de Groot M, Sampson JA: The effects of psychiatric disorders and symptoms on quality of life in patients with type I and type II diabetes mellitus. Qual Life Res 1997; 6:11–20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Dunn SM, Bryson JM, Hoskins PL, Alford JB, Handelsman DJ, Turtle JR: Development of the diabetes knowledge (DKN) scales: forms DKNA, DKNB, and DKNC. Diabetes Care 1984; 7:36–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE: Assessing diabetes self-management: the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Questionnaire, in Handbook of Psychology and Diabetes: A Guide to Psychological Measurement in Diabetes Research and Practice. Edited by Bradley C. Berkshire, UK, Harwood Academic, 1994, pp 351–375Google Scholar

24. Clark DO, Von Korff M, Saunders K, Baluch WM, Simon GE: A chronic disease score with empirically derived weights. Med Care 1995; 33:783–795Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Unützer J, Simon GE, Pabiniak C, Bond K, Katon W: The use of administrative data to assess quality of care for bipolar disorder in a large staff model HMO. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2000; 22:1–10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Rand CS, Weeks K: Measuring adherence with medication regimens in clinical care and research, in The Handbook of Health Behavior Change, 2nd ed. Edited by Shumaker SA, Schron EB. New York, Springer, 1998, pp 114–132Google Scholar

27. Feeney J, Ryan S: Attachment style and affect regulation: relationships with health behavior and family experiences of illness in a student sample. Health Psychol 1994; 13:334–345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Dozier M: Attachment organization and treatment use for adults with serious psychopathological disorders. Dev Psychopathol 1990; 2:47–60Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Klein R, Klein BE: Relation of glycemic control to diabetic complications and health outcomes. Diabetes Care 1998; 21(suppl 3):C39–C43Google Scholar

30. Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR: Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. J Pers Soc Psychol 1997; 73:1092–1106Google Scholar

31. Jacobson AM, Adler AG, Derby L, Anderson BJ, Wolfsdorf JI: Clinic attendance and glycemic control: study of contrasting groups of patients with IDDM. Diabetes Care 1991; 14:599–601Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar