Abnormal Neurologic Maturation in Adolescents With Early-Onset Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study evaluated neurologic functioning in adolescents with schizophrenia with onset of psychosis before age 13. METHOD: The authors administered a structured neurologic examination to 21 adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia and 27 healthy age- and sex-matched comparison subjects. RESULTS: The adolescents with schizophrenia had a high frequency of neurologic abnormalities. Neurologic signs decreased with age in the healthy comparison subjects but not in the subjects with schizophrenia. CONCLUSIONS: The adolescents with schizophrenia had a high burden of neurologic impairment and a pattern of abnormalities similar to that of adults with schizophrenia. The persistence of neurologic signs in the adolescents with schizophrenia, which faded with age in the healthy comparison adolescents, supports earlier evidence of a delay in or failure of normal brain development during adolescence.

Neurologic abnormalities are common in adults with schizophrenia (1–17). Patients with schizophrenia exhibit both more nonlocalizing and localizing signs. Neurologic dysfunction is present in those naive to neuroleptic treatment (3, 18, 19) and in patients treated with neuroleptics, even if signs possibly due to neuroleptic medication are excluded (12, 14).

Schizophrenia can appear during childhood with psychiatric symptom profiles and neurobiological abnormalities similar to those found in adults (20–25). The few available early studies of “schizophrenic children” found neurologic dysfunction in up to 95% of patients (26–29) but lacked clear diagnostic criteria, often including children with pervasive developmental disorders, organic brain syndrome, and mental retardation.

In this study, a comprehensive neurologic examination was performed on adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia and an age- and sex-matched healthy comparison group. We proposed that neurologic dysfunction would be more frequent in the patients with schizophrenia than in the healthy comparison adolescents and would be similar in kind to that found in adults with schizophrenia.

Method

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Institute for Mental Health. After receiving a full explanation of study procedures, parents or guardians provided written consent; subjects gave their assent to the examination. Psychiatric diagnosis was determined by a review of records, interviews, and psychiatric examinations. Full-scale IQ was estimated from the vocabulary and block design subtests of the WISC-R (30). Brain structural analysis was performed as previously reported (31–34). A standardized neurologic examination was also performed. Individual test items were scored as normal or abnormal, present or absent, or untestable. Patients were examined after at least 1 week with no medication. It was not possible to blind the examiners to patient diagnosis because of active psychotic symptoms in the patients.

We studied 21 adolescents aged 12–17 who met DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia with an onset of psychosis before age 13. Exclusionary criteria included a premorbid WISC-R full-scale IQ <70, other neurological or significant medical disorders, active substance abuse, or significant hearing or visual deficits. The subjects were participants in a larger study of refractory childhood-onset schizophrenia (22, 31, 35–37). Additionally, 27 psychiatrically healthy adolescents aged 10–17 who met the same exclusionary criteria served as a comparison group.

Means, standard deviations, and ranges are reported. Age was compared by means of a two-tailed t test. Otherwise, cohorts were compared by means of the Wilcoxon ranked sum test, with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. Chi-squares were used to compare frequency of occurrence. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated to detect significant correlations among age, IQ, total brain volume and ventricular volume with individual neurological signs, grouped subcategories of neurologic function, and total number of signs. Correlations were compared by means of Fisher’s r-to-z transformation. Interrater agreement for eight subjects was measured with the kappa statistic and with percent agreement for low-frequency signs.

Results

The cohort with childhood-onset schizophrenia was made up of eight girls and 13 boys with a mean age of 14 years (SD=1). The healthy comparison group was composed of 12 girls and 15 boys with a mean age of 13 years (SD=2). Neither age (t=1.56, N=21, 27, p<0.13) nor sex distribution (χ2=1.96, df=1, p<0.67) differed between the two groups. After onset of symptoms, the subjects with childhood-onset schizophrenia had an estimated mean full-scale IQ of 77 (SD=22, range=48–120), which differed significantly from that of the healthy comparison subjects (estimated mean full-scale IQ=121, SD=12, range=97–141) (Wilcoxon z=4.21, N=48, p<0.0001). Interrater reliability was good; kappa was >0.40, and percent agreement was >75% on all items, except four frontal release signs (snout, palmomental, glabellar tap, and jaw jerk), in which percent agreement ranged from 43% to 57%. Isolated abnormalities of cranial nerves, primary sensation, and strength occurred equally in both groups. Gaze impersistence was more common in the subjects with childhood-onset schizophrenia (χ2=14.15, df=1, p<0.001). Similarly, sensory integration face-hand test results were more frequently abnormal in the patients with childhood-onset schizophrenia (χ2=8.44, df=1, p<0.004). A higher incidence of increased passive tone while reinforcing movements were made with the opposite arm was especially common in healthy comparison adolescents younger than age 15, whereas the adolescents with childhood-onset schizophrenia were significantly more likely to exhibit increased passive tone in the absence of reinforcement, independent of age (χ2=7.31, df=1, p<0.03). Corticospinal tract signs were also significantly more common in the cohort with childhood-onset schizophrenia (χ2=7.31, df=1, p<0.03). Coordination was often abnormal in both groups; however, all of the healthy comparison adolescents with poor coordination were younger than age 15 (p<0.04, Fisher’s exact test), whereas no grouping by age was present in the cohort with childhood-onset schizophrenia (p>0.99, Fisher’s exact test). Choreiform movements were similarly significantly clustered in the younger healthy comparison adolescents (p<0.02, Fisher’s exact test) but were equally present in both younger and older adolescents with childhood-onset schizophrenia (p>0.99, Fisher’s exact test).

Twelve healthy comparison adolescents but only three adolescents with childhood-onset schizophrenia exhibited no primitive reflexes (χ2=0.03, df=1, p<0.056). The number of primitive reflexes was significantly inversely correlated with age in the healthy comparison cohort (rs=–0.57, N=27, p<0.002) but not in the cohort with childhood-onset schizophrenia (rs=0.05, N=21, p<0.84).

At least one sign was present at neurologic examination in all (100%) of the adolescents with childhood-onset schizophrenia and in 26 (96%) of the 27 healthy comparison subjects. The group with schizophrenia had a mean of 6 (SD=2, range=2–10) signs per subject. The healthy comparison group had a mean of 4 (SD=2, range=0–8) signs per subject (Wilcoxon z=–3.30, N=18, 27, p<0.001). Because examination of primitive reflexes can have low interrater reliability (38), analyses were repeated with those signs excluded. Significant differences persisted.

No significant correlations were found between either the total number or type of abnormalities by specific neurologic subcategory and either ventricular size or total brain volume. Full-scale IQ correlated only inversely with the number of primitive reflexes in the healthy comparison cohort (rs=–0.64, N=27, p<0.02) but not in the patients.

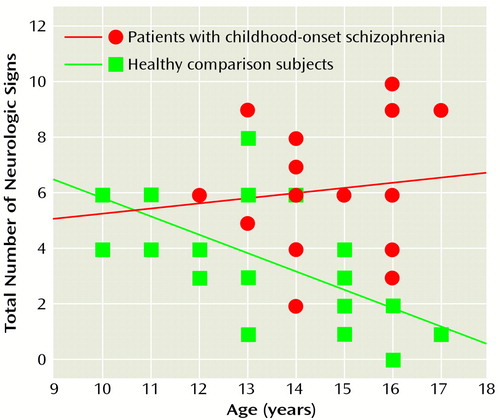

The total number of neurologic signs decreased with age in the healthy comparison group (rs=–0.73, N=27, p<0.0001) but not in the group with childhood-onset schizophrenia (rs=–0.07, N=18, p<0.78). These correlations differed significantly (Wilcoxon z=–2.56, p=0.005, Fisher’s r-to-z transformation) (Figure 1).

Discussion

This study uniquely demonstrates a failure of neurological maturation in patients with early-onset schizophrenia during adolescence. Not only were the patients with childhood-onset schizophrenia more neurologically impaired than the healthy subjects (with a pattern of abnormalities similar to that seen in patients with adult-onset schizophrenia), but they also failed to lose the signs that fade during normal development.

The high frequency of neurologic signs seen in the healthy subjects likely reflected the inclusive nature of the examination and the subjects’ ages. Our results are comparable with those of other studies of healthy subjects. Rossi et al. (39) found neurologic signs in 95% of normal adults on a 28-item battery of soft signs, with a mean of 4.1 signs per subject. Kennard found neurologic abnormalities in 60% of the healthy children he studied (28); he and Rutter et al. found chorea in 5%–25% of healthy subjects (40).

The frequency of neurologic signs found in our subjects with childhood-onset schizophrenia is also comparable to the 92%–100% prevalence reported in other series of both adult (9, 10, 13, 14) and pediatric (28) patients with schizophrenia. Our high prevalence of abnormal signs may additionally reflect the fact that our cohort with schizophrenia was severely ill and treatment-resistant. Our high frequency is also consistent with theories that pediatric schizophrenia results from an early cerebral insult and is a more “biologically driven” form of the disease than later-onset schizophrenia (41, 42).

Gittelman and Birch (27) found neurologic dysfunction more common in children with schizophrenia with lower IQs than in those with higher IQs. Although the estimated full-scale IQ in our subjects with childhood-onset schizophrenia was significantly lower than that of the healthy comparison group, the only correlation found was an inverse relation with the number of primitive reflexes in the healthy comparison group. It is likely that the lower IQ and higher number of neurologic signs found in the subjects with childhood-onset schizophrenia are both reflections of the underlying illness. It would be difficult to match the individuals in each group by IQ and still consider the healthy comparison cohort neurologically normal.

All patients with childhood-onset schizophrenia were medication-free for at least 1 week before the neurological examination; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that the presence of some signs was medication-related. Although tardive dyskinesia may be less frequent in children than in adults (43, 44), withdrawal dyskinesias are especially common in children during the first 6 weeks after neuroleptic discontinuation (45–48).

Primitive reflexes, present during early life, are suppressed as cortical areas mature (49). Their reappearance may represent a loss of hemispheric inhibition of the brainstem. Our examination detected a maturational loss of primitive reflexes in the healthy comparison group that was lacking in the cohort with schizophrenia. Similarly, although hypertonia, impaired coordination, chorea, and the total number of neurologic signs decreased with age in the healthy comparison cohort, they persisted in the adolescents with schizophrenia, indicating a failure of normal maturation. We have previously detected other deviations from normal development in subjects with childhood-onset schizophrenia during adolescence, including a progressive loss of cerebral and subcortical volume (31, 32) and a decline in full-scale IQ due to a lack of new learning (22, 50). The present study provides additional evidence of an abnormal neurodevelopmental course in patients with early-onset schizophrenia during adolescence.

Received Dec. 7, 1999; revision received June 19, 2000; accepted July 5, 2000. From the Child Psychiatry Branch, NIMH. Address reprint requests to Dr. Karp, 10/5S-209, NINDS, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. Correlation of Age to Number of Neurologic Signs for Adolescents With Childhood-Onset Schizophrenia and Healthy Comparison Subjects

1. de Cataldo S, Rossi A, Di Michele V, Manna V, Casacchia M: Soft neurological dysfunction and gender in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160:423–424Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Cox SM, Ludwig AM: Neurological soft signs and psychopathology, I: findings in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1979; 167:161–165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Gupta S, Andreasen NC, Arndt S, Flaum M, Schultz SK, Hubbard WC, Smith M: Neurological soft signs in neuroleptic-naive and neuroleptic-treated schizophrenic patients and in normal comparison subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:191–196Link, Google Scholar

4. Flashman LA, Flaum M, Gupta S, Andreasen NC: Soft signs and neuropsychological performance in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:526–532Link, Google Scholar

5. Johnstone EC, Owens DG: Neurological changes in a population of patients with chronic schizophrenia and their relationship to physical treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1981; 291:103–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Heinrichs DW, Buchanan RW: Significance and meaning of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:11–18Link, Google Scholar

7. Kinney DK, Woods BT, Yurgelun-Todd D: Neurologic abnormalities in schizophrenic patients and their families, II: neurologic and psychiatric findings in relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:665–668Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kinney DK, Yurgelun-Todd DA, Woods BT: Neurologic signs in patients with paranoid and nonparanoid schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 4:447–449Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lane A, Colgan K, Moynihan F, Burke T, Waddington JL, Larkin C, O’Callaghan E: Schizophrenia and neurological soft signs: gender differences in clinical correlates and antecedent factors. Psychiatry Res 1996; 64:105–114Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Manschreck TC, Ames D: Neurologic features and psychopathology in schizophrenic disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1984; 19:703–719Medline, Google Scholar

11. Torrey EF: Neurological abnormalities in schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry 1980; 15:381–388Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kinney DK, Yurgelun-Todd DA, Woods BT: Hard neurologic signs and psychopathology in relatives of schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Res 1991; 39:45–53Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Ismail BT, Cantor-Graae E, Cardenal S, McNeil TF: Neurological abnormalities in schizophrenia: clinical, etiological and demographic correlates. Schizophr Res 1998; 30:229–238Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Ismail B, Cantor-Graae E, McNeil TF: Neurological abnormalities in schizophrenic patients and their siblings. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:84–89Link, Google Scholar

15. Rochford JM, Detre T, Tucker GJ, Harrow M: Neuropsychological impairments in functional psychiatric diseases. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1970; 22:114–119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Woods BT, Short MP: Neurological dimensions of psychiatry. Biol Psychiatry 1985; 20:192–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Woods BT, Kinney DK, Yurgelun-Todd D: Neurologic abnormalities in schizophrenic patients and their families, I: comparison of schizophrenic, bipolar, and substance abuse patients and normal controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:657–663Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Sanders RD, Keshavan MS, Schooler NR: Neurological examination abnormalities in neuroleptic-naive patients with first-break schizophrenia: preliminary results. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1231–1233Google Scholar

19. Rubin P, Vorstrup S, Hemmingsen R, Andersen HS, Bendsen BB, Stromso N, Larsen JK, Bolwig TG: Neurological abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder at first admission to hospital: correlations with computerized tomography and regional cerebral blood flow findings. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90:385–390Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Nicolson R, Rapoport JL: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: rare but worth studying. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:1418–1428Google Scholar

21. Bertolino A, Kumra S, Callicott JH, Mattay VS, Lestz RM, Jacobsen L, Barnett IS, Duyn JH, Frank JA, Rapoport JL, Weinberger DR: Common pattern of cortical pathology in childhood-onset and adult-onset schizophrenia as identified by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1376–1383Google Scholar

22. Jacobsen LK, Rapoport JL: Research update: childhood-onset schizophrenia: implications of clinical and neurobiological research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1998; 39:101–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Beitchman JH: Childhood schizophrenia: a review and comparison with adult-onset schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1985; 8:793–814Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Werry JS: Child and adolescent (early onset) schizophrenia: a review in light of DSM-III-R. J Autism Dev Disord 1992; 22:601–624Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Karno M, Norquist GS: Schizophrenia: epidemiology, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 6th ed. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1995, pp 902–910Google Scholar

26. Birch HG, Hertzig ME: Etiology of schizophrenia: an overview of the relation of development to atypical behavior, in Proceedings of the First Rochester International Conference on Schizophrenia: The Origins of Schizophrenia. Edited by Romano J. Amsterdam, Excerpta Medica, 1967, pp 92–110Google Scholar

27. Gittelman M, Birch HG: Childhood schizophrenia: intellect, neurologic status, perinatal risk, prognosis, and family pathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1967; 17:16–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Kennard MA: Value of equivocal signs in neurologic diagnosis. Neurology 1960; 10:753–764Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Goldfarb W: Factors in the development of schizophrenic children: an approach to subclassification, in Proceedings of the First Rochester International Conference on Schizophrenia: The Origins of Schizophrenia. Edited by Romano J. Amsterdam, Excerpta Medica, 1967, pp 70–91Google Scholar

30. Sattler JM: Assessment of Children. San Diego, Jerome M Sattler, 1992, p 851Google Scholar

31. Rapoport JL, Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Hamburger S, Jeffries N, Fernandez T, Nicolson R, Bedwell J, Lenane M, Zijdenbos A, Paus T, Evans A: Progressive cortical change during adolescence in childhood-onset schizophrenia: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:649–654Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Giedd JN, Jeffries NO, Blumenthal J, Castellanos FX, Vaituzis AC, Fernandez T, Hamburger SD, Liu H, Nelson J, Bedwell J, Tran L, Lenane M, Nicolson R, Rapoport JL: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: progressive brain changes during adolescence. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:892–898Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Frazier JA, Giedd JN, Hamburger SD, Albus KE, Kaysen D, Vaituzis C, Rajapakse JC, Lenane MC, McKenna K, Jacobsen LK, Gordon CT, Breier A, Rapoport JL: Brain anatomic magnetic resonance imaging in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:617–624Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Frazier JA, Giedd JN, Kaysen D, Albus K, Hamburger S, Alaghband-Rad J, Lenane MC, McKenna K, Breier A, Rapoport JL: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: brain MRI rescan after 2 years of clozapine maintenance treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:564–566Link, Google Scholar

35. Gordon CT, Frazier JA, McKenna K, Giedd J, Zametkin A, Zahn T, Hommer D, Hong W, Kaysen D, Albus KE, Rapoport JL: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: an NIMH study in progress. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:697–712Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Alaghband-Rad J, McKenna K, Gordon CT, Albus KE, Hamburger SD, Rumsey JM, Frazier JA, Lenane MC, Rapoport JL: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: the severity of premorbid course. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1273–1283Google Scholar

37. Frazier JA, Gordon CT, McKenna K, Lenane M, Jih D, Rapoport JL: An open trial of clozapine in 11 adolescents with childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:658–663Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Sanders RD, Forman SD, Pierri JN, Baker RW, Kelley ME, Van Kammen DP, Keshavan MS: Inter-rater reliability of the neurological examination in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1998; 29:287–292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Rossi A, de Cataldo S, Di Michele V, Manna V, Ceccoli S, Stratta P, Casacchia M: Neurological soft signs in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:735–739Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Rutter M, Tizard J, Whitmore K: Neurological aspects of intellectual retardation and specific reading retardation, in Education, Health, and Behaviour: Psychological and Medical Study of Childhood Development. Edited by Rutter M, Tizard J, Whitmore K. London, John Wiley & Sons, 1970, pp 54–74Google Scholar

41. Fish B: Neurobiologic antecedents of schizophrenia in children: evidence for an inherited, congenital neurointegrative defect. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977; 34:1297–1313Google Scholar

42. Asarnow JR, Tompson MC, Goldstein MJ: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: a follow-up study. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:599–617Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Weiner WJ, Lang AE: Tardive Dyskinesia in Movement Disorders: A Comprehensive Survey. New York, Futura, 1989, pp 645–684Google Scholar

44. Campbell M, Grega DM, Green WH, Bennett WG: Neuroleptic-induced dyskinesias in children. Clin Neuropharmacol 1983; 6:207–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Campbell M, Cueva JE: Psychopharmacology in child and adolescent psychiatry: a review of the past seven years, part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1124–1132Google Scholar

46. Campbell M, Adams P, Perry R, Spencer EK, Overall JE: Tardive and withdrawal dyskinesia in autistic children: a prospective study. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:251–255Medline, Google Scholar

47. Campbell M, Spencer EK: Psychopharmacology in child and adolescent psychiatry: a review of the past five years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1988; 27:269–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Shay J, Sanchez LE, Cueva JE, Armenteros JL, Overall JE, Campbell M: Neuroleptic-related dyskinesias and stereotypies in autistic children: videotaped ratings. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:359–363Medline, Google Scholar

49. Magee KR: Clinical analysis of reflexes, in Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Edited by Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1969, pp 237–256Google Scholar

50. Bedwell JS, Keller B, Smith AK, Hamburger S, Kumra S, Rapoport JL: Why does postpsychotic IQ decline in childhood-onset schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1996–1997Google Scholar