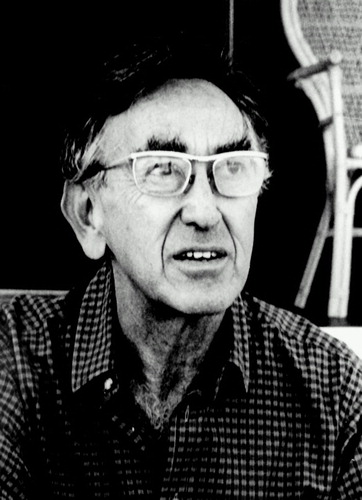

Norman E. Zinberg,M.D., 1922–1989

Norman Zinberg was a singularly engaging and challenging person and teacher. These qualities endeared him to many but made him controversial and threatening to others. After completing his training in Maryland he was drawn to Boston and the Beth Israel Hospital to study and work under renowned psychoanalysts, particularly Dr. Greta Bibring. In contrast to the regal and often remote qualities of many of his psychoanalytic mentors, there was an ease of access and openness about Norman that engaged a whole generation of students and collaborators. Norman was especially influential in teaching nonpsychiatric physicians; his weekly medical rounds at the Beth Israel Hospital were described as “master classes in the best of liaison psychiatry.”

Norman’s extensive interests included medical and social consultation, gerontology, group and organization theory, the addictions, and patients’ rights to privacy and confidentiality. He was peerless as a supervisor for understanding our patients’ distress and conflicts in psychotherapy, and he distinguished himself further by influencing government policy makers, as well as scientists and clinicians, on many important and controversial social issues of our time.

In the early 1970s, Norman joined the Department of Psychiatry at The Cambridge Hospital when it was just starting its drug abuse treatment programs. He combined enthusiasm with erudition. He was always eager and available to staff and trainees, as they mastered the day-to-day challenges of understanding and providing services for the many patients who came to our hospital for their drug dependency and alcoholism. Norman was pivotal in earning The Cambridge Hospital a reputation for treating patients with addictive illness “well.”

One of his most important contributions in the addictions field was to bring a humanistic view to substance use disorders and cut through the then-prevailing stereotypes of an addictive personality. In a series of publications he explored the interaction between “set, setting, and the [psychoactive] effects of drugs” and the varied patterns of drug use and abuse in different individuals. And as was so often the case with Norman Zinberg, he was a league ahead of his contemporaries, anticipating crucial controversies we now face in medical/psychiatric practice, when he published several important papers on privacy and confidentiality in clinical practice. He was appointed to the national AIDS Commission, again demonstrating his active involvement with the compelling clinical and social issues of our time. Indicative of his influence on public policy, in 1988 Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan credited Norman for invaluable advice that guided the passage of a bill to reduce drug abuse through treatment and education.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Khantzian, Hathorne Mental Health Units, Tewksbury Hospital, 365 East St., Tewksbury, MA 01876; [email protected] (e-mail). Photograph courtesy of Renate Ponsold Motherwell. A portion of this essay is based on a Memorial Minute prepared for the Harvard Faculty of Medicine. Members of the committee were Golda Edinburg, Janice Kaufman, David Lewis, John Mack, Robert Millman, Howard Shaffer, and Edward Khantzian (chairperson).

Norman Zinberg