Comorbid Anxiety Disorders in Depressed Elderly Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Anxiety disorders are common in adults with depressive disorders, but several studies have suggested a relatively low prevalence of anxiety disorders in older individuals with depression. This cross-sectional study measured current and lifetime rates and associated clinical features of anxiety disorders in depressed elderly patients. METHOD: History of anxiety disorders was assessed by using a structured diagnostic instrument in 182 depressed subjects aged 60 and older seen in primary care and psychiatric settings. Associations between comorbid anxiety disorders and baseline characteristics were measured. The modified structured instrument allowed detection of symptoms that met inclusion criteria for generalized anxiety disorder in a depressive episode. RESULTS: Thirty-five percent of older subjects with depressive disorders had at least one lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis, and 23% had a current diagnosis. The most common current comorbid anxiety disorders were panic disorder (9.3%), specific phobias (8.8%), and social phobia (6.6%). Symptoms that met inclusion criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, measured separately, were present in 27.5% of depressed subjects. Presence of a comorbid anxiety disorder was associated with poorer social function and a higher level of somatic symptoms. Symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder were associated with a higher level of suicidality. CONCLUSIONS: Contrary to previous reports, the present study found a relatively high rate of current and lifetime anxiety disorders in elderly depressed individuals. Comorbid anxiety disorders and symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder were associated with a more severe presentation of depressive illness in elderly subjects.

Anxiety is commonly found in adults with depressive disorders, both as a symptom and as a comorbid disorder such as generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or a phobia. An estimated 85% of adults with depression experience significant symptoms of anxiety (1), and 58% have a diagnosable anxiety disorder during their lifetime (2). The National Comorbidity Survey (2) found elevated rates of comorbid current social phobia (27.1%), simple phobia (24.3%), generalized anxiety disorder (17.2%), and panic disorder (9.9%) in adults with major depression in the community. Reported rates of comorbidity are even higher in clinical samples seen in primary care (3, 4) and psychiatric settings (5). The prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in depression is much higher than predicted by chance. In particular, symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder are very prevalent in major depression, but the diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder is much less prevalent because of the DSM hierarchical exclusion rule that prevents this diagnosis if symptoms occur only during depressive episodes. In younger adults, comorbid anxiety disorders have important prognostic value, predicting greater chronicity and severity of depressive illness (6, 7), lower rates of treatment response (8, 9), and higher suicide risk (10, 11).

Geriatric anxiety disorders have received less attention, perhaps because of existing opinion that anxiety becomes rarer with older age (12). Epidemiologic data support this view, finding lower rates of anxiety disorders in community-dwelling elderly populations than in similar younger-aged populations (13). Some studies have found especially low rates of panic disorder and social phobia in elderly subjects (12, 14). Comorbid anxiety disorders may be far more prevalent in the depressed elderly, but the absence of large-scale epidemiological studies addressing psychiatric comorbidity in the elderly leaves this possibility unconfirmed. Two small community studies (15, 16) found lower rates of comorbid generalized anxiety disorder, phobic anxiety, and especially panic attacks in depressed elderly subjects than were found in similar studies involving younger adults (5, 17). Three prior studies in clinical settings assessed the rate of comorbid anxiety in depressed elderly patients. One study found that 38% of 45 elderly outpatients with major depression also met DSM-III-R criteria for an anxiety disorder (18). In a study of elderly nursing home residents, 65% of those with major depression also displayed concurrent symptoms of anxiety, but very low rates of panic attacks were seen (19). The study report did not state how many patients met full criteria for an anxiety disorder diagnosis. In a retrospective study by our group involving 336 elderly psychiatric inpatients and outpatients with major depression, one-third to one-half had severe anxiety symptoms, but only 8% had diagnosable anxiety disorders (20). In this study, only panic disorder, OCD, and phobias were considered; generalized anxiety disorder was not included. The results of these three studies conducted in treatment settings suggest that comorbid anxiety disorders are less common in elderly patients with major depression than in their younger adult counterparts.

The study reported here was conducted to further investigate the rate of comorbid anxiety disorders in elderly patients with depressive disorders. Because variability in the results of previous studies may have been due to characteristics of the specific settings where subjects were recruited, the study reported here recruited patients from a variety of clinical settings. The aim was to provide a heterogeneous study group who could be compared to subjects in other studies conducted in a range of clinical settings.

Method

Subjects were recruited by the Intervention Research Center for Late-Life Mood Disorders at the University of Pittsburgh. They were participants in either of two studies. The first study, a randomized comparison of nortriptyline and paroxetine, included 80 subjects over age 60 (21). Subjects met criteria for a nonpsychotic unipolar major depressive episode and were recruited from the inpatient geriatric psychiatry units and the outpatient late-life depression clinic of Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, a teaching hospital and referral center for an urban catchment area. The second study, which examined depression in primary care, included 102 subjects age 60 years and older (22). They were recruited from two ambulatory internal medicine centers and had significant depressive symptoms as defined by a score of 11 or greater on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale) (23). Of these, 36 subjects met criteria for a nonpsychotic unipolar major depressive episode. The remaining 66 subjects with significant depressive symptoms did not meet criteria for a major depressive episode.

In both studies, all subjects were evaluated by trained, master’s-level clinicians, supervised by a psychiatrist, who used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (24). Patients with alcohol or substance abuse or dependency in the past year or with dementia were excluded. All subjects gave written informed consent before participating in the studies. The following instruments were used to evaluate subjects’ baseline characteristics: the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (25), the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (26), the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (27), and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale—Geriatrics (28). In addition, to assess somatic symptoms, the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale (29) was given at baseline.

Data from the evaluations were analyzed to determine the lifetime and current rates of the following DSM-IV anxiety disorders in the two groups: panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia), agoraphobia without panic disorder, OCD, specific phobias, social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The SCID excludes the possibility of making a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder in subjects with a major depressive episode, even if the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder exist outside of depressive episodes. However, in this study, the SCID was modified by removing this exclusion; individuals meeting inclusion criteria for generalized anxiety disorder are described in this study as having symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. The rate of current symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder was determined in this manner.

The percentage of subjects with at least one anxiety disorder, current or lifetime, as well as the percentage with two or more anxiety disorders, was determined. Rates were calculated for the entire group and for four subgroups: primary care patients with significant depressive symptoms, primary care patients with major depression, psychiatric outpatients with major depression, and psychiatric inpatients with major depression. Chi-square analysis tested for significant differences between the subgroups. To control for multiple observations, we used a significance level of p<0.003. Because symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder did not represent an anxiety disorder diagnosis, they were not included in the overall rates. For subjects with major depression in primary care and psychiatric settings, the percentage of subjects with recurrent major depression was determined. Recurrent major depression was defined as at least two major depressive episodes separated by at least 2 months of remission. A chi-square analysis was performed to determine whether the presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder was associated with different rates of single versus recurrent major depression. For subjects in the psychiatric settings only, age at onset of the first depressive episode and duration of the current episode were elicited, and t tests were performed to compare groups on these variables. Also, an analysis of variance, controlling for group, was performed to detect whether the presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder was associated with duration of the current depressive episode (with a natural log transformation to normalize distribution) or with age at onset of the first depressive episode.

For purposes of further analysis, all subjects were divided into two groups: those with no current SCID anxiety diagnosis and those with one or more anxiety diagnoses (again excluding symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder as a diagnosis). A t test was performed to compare the current severity of depression in the two groups, measured as total Hamilton depression scale score minus scores for the scale’s two questions about anxiety (item 10, on psychological anxiety, and item 11, on somatic anxiety). An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to test the effects of comorbid anxiety disorders on baseline characteristics, with severity of depression as a covariate. The baseline characteristics measured were the GAS score, scores on the physical and social function scales of the Short-Form Health Survey, the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale—Geriatrics score, level of suicidality as measured by the score on the suicide item of the Hamilton depression scale, and somatic symptoms as measured by scores on the somatic subscales of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale (neurologic, autonomic, and other). To test whether symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder independently affected these characteristics, the ANCOVAs were repeated with generalized anxiety disorder symptoms as an additional covariate.

Results

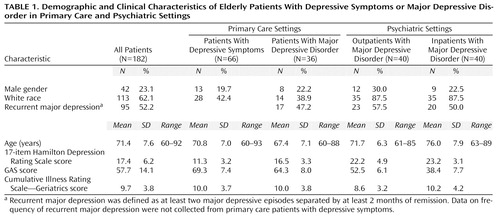

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 182 elderly subjects with major depression or significant depressive symptoms are shown in Table 1. The four subgroups represented a range of patients in terms of age, race, and severity of depressive symptoms. Of the 182 subjects, 70 were taking at least one psychotropic medication at the time of the SCID: benzodiazepines (37 subjects) at an average lorazepam equivalency dose of 0.9 mg/day, tricyclics (22 subjects) at an average imipramine equivalency dose of 93 mg/day, fluoxetine (five subjects) at an average dose of 22 mg/day, sertraline (seven subjects) at an average dose of 54 mg/day, fluvoxamine (one subject) at 300 mg/day, paroxetine (21 subjects) at an average dose of 21 mg/day, trazodone (five subjects) at an average dose of 122 mg/day, nefazodone (one subject) at 300 mg/day, buspirone (one subject) at 15 mg/day, and fluphenazine (one subject) at 3 mg/day.

Table 2 shows the lifetime and current rates (concurrent to the index depressive episode) of anxiety disorders in the entire patient group. Symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder are not included in the combined rate of anxiety disorders. Table 2 also shows the lifetime and current rates of anxiety disorders of the four subgroups and chi-square analysis of differences between subgroups.

The rate of symptoms meeting inclusion criteria for current generalized anxiety disorder in the whole group was 27.5%. In the primary care subgroups of those with significant depressive symptoms and those with major depression, the rates were 13.6% and 30.6%, respectively. In the outpatient and inpatient psychiatric subgroups, the rates were 30.0% and 45.0%, respectively. Chi-square analysis showed a significant difference between subgroups in the rate of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms (c2=12.81, df=3, p=0.005).

In subjects with major depression (N=116), the presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder was not associated with greater likelihood of recurrent episodes rather than a single episode of depression (c2=0.04, df=1, p=0.84). In the psychiatric subjects with major depression (N=80), the mean age of onset of major depression was 57.1 years (SD=18.4), and the mean duration of the current depressive episode was 80.3 weeks (SD=165.4). The outpatients had a younger age at onset than the inpatients (mean=52.7 years, SD=19.6, versus mean=61.4 years, SD=16.1; t=–2.16, df=78, p=0.03) and a longer duration of the current depressive episode (mean=107.9 weeks, SD=217.8, versus mean=52.8 weeks, SD=80.2; t=2.15, df=78, p=0.04). Controlling for group, the presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder was not associated with duration of the current depressive episode (F=0.42, df=1, 77, p=0.52), but there was a trend toward a significant association between presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder and earlier age at onset of first depressive episode (F=3.74, df=1, 77, p=0.057).

There was no significant difference in severity of depressive symptoms between patients with a current comorbid anxiety disorder and patients without the comorbid disorder (Hamilton depression scale score minus scores for the two anxiety items, mean=14.5, SD=5.1, versus mean=13.6, SD=5.5; t=–0.94, df=178, p=0.35). ANCOVAs were used to test the effects of comorbid anxiety disorder (not including symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder), controlling for severity of depressive symptoms. Comorbid anxiety disorders were associated with a lower mean social function score on the Short-Form Health Survey (F=6.8, df=1, 168, p=0.01) and greater severity of symptoms (such as sweating, nausea, and palpitations) on the autonomic somatic subscale of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale (F=5.39, df=1, 174, p=0.02). There was a trend toward a significantly lower mean GAS score in patients with comorbid anxiety disorders (F=3.51, df=1, 175, p=0.06). There was no significant association between comorbid anxiety disorders and physical function as measured by the Short-Form Health Survey (F=0.13, df=1, 169, p=0.72), the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale—Geriatrics score (F=0.0, df=1, 142, p=0.99), and scores on the neurologic somatic subscale (F=1.29, df=1, 173, p=0.26) and other somatic symptoms subscale (F=0.94, df=1, 171, p=0.33) of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale. Comorbid anxiety disorders were not associated with greater likelihood of suicidal ideation (F=0.05, df=1, 177, p=0.82). Depressive severity was a significant covariate for all variables at the p<0.001 level (GAS: F=341.66, df=1, 175; social function: F=52.14, df=1, 168; UKU Side Effect Rating Scale neurologic somatic subscale: F=45.20, df=1, 173; autonomic somatic subscale: F=52.66, df=1, 174; other somatic symptoms subscale: F=28.84, df=1, 171; and suicidal ideation: F=75.05, df=1, 177) except physical function (F=0.04, df=1, 169, p=0.85) and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale—Geriatrics score (F=0.82, df=1, 142, p=0.37).

The ANCOVAs were repeated to include symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder; they were significantly associated with greater severity of depressive symptoms (F=12.73, df=1, 177, p<0.001). In addition, after controlling for depressive severity and comorbid anxiety disorders, symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder were associated with greater likelihood of suicidal ideation (F=12.45, df=1, 176, p<0.001). They were not significantly associated with GAS score (F=2.87, df=1, 174, p=0.09), physical function (F=0.03, df=1, 168, p=0.87), social function (F=0.06, df=1, 167, p=0.80), Cumulative Illness Rating Scale—Geriatrics score (F=0.05, df=1, 141, p=0.82), or UKU Side Effect Rating Scale score (F=1.47, df=1, 163, p=0.23).

Discussion

This study examined the current and lifetime rates of anxiety disorders in depressed subjects seen in a variety of clinical settings—psychiatric inpatients, psychiatric outpatients, and primary care patients. We found a high rate of lifetime (35%) and current (23%) comorbid anxiety disorders, mainly panic disorder and phobias. We found a low rate of OCD and PTSD. The 23% rate of current comorbid anxiety disorders in this study is similar to the 38% rate reported for a small group of elderly psychiatric patients with major depression (18). It is also similar to the prevalence of 41% in a large-scale study of adults with major depression or dysthymia in primary care (3).

The rate of comorbid anxiety disorders in this study is four- to seven-fold higher than in studies of elderly persons in the community (13). In particular, the frequency of panic disorder (9.3%) is almost two orders of magnitude greater than the 0.1%–0.3% prevalence previously reported in community elderly (12, 13). This finding is consistent with findings in younger adults that anxiety disorders are much more common in depressed individuals (2), especially those seen in clinical settings (3, 5). It is also consistent with previously published smaller-scale reports (18, 19) on comorbid anxiety in depressed elderly in clinical settings. It should also be noted that the rates of current anxiety disorder in this report are higher than rates we previously found in a retrospective analysis of a different group of older depressed patients (20). Because of these previous findings, the present study was designed prospectively, in collaboration with an anxiety disorders specialist (M.K.S.). This increased attention to comorbidity has likely improved the group’s sensitivity to the presentation of anxiety disorders, allowing more comorbid anxiety disorders to be detected despite the use of the same structured instrument. This should serve as an object lesson to clinicians and clinical researchers, regarding the need to focus on comorbid disorders in order to have adequate sensitivity to find them.

The relatively high rates of comorbidity in clinical settings has been attributed to the fact that depressed elderly with anxiety may be more likely to seek treatment, as suggested in younger adults (30). This increased treatment seeking could be due to greater physical illness or greater psychological distress, both of which are associated with geriatric depression and anxiety disorders. It is especially pertinent for clinicians to know that comorbidity can be much greater in clinical settings than in community studies.

Our study found differences in rates of several anxiety disorders between the various settings. Corrected for multiple observations, the two significant findings were lower rates of one or more current anxiety disorder and of current panic disorder in the outpatient psychiatric setting, suggesting that some findings were site-specific. It should not be surprising that inpatients with more severe depression had a greater likelihood of comorbidity. The higher rate in primary care settings, on the other hand, may be due to differences in methods of recruiting subjects; for example, subjects in the primary care study were recruited by a cutoff score on the CES-D Scale, an instrument that may screen for nonspecific mental distress in addition to specifically screening for depression (31). Alternately, it may be that subjects in psychiatric settings were more focused on their depression, leading them to underreport symptoms they did not consider relevant, such as specific phobias. Subject bias based on clinical state has been reported in other settings as well (32). Overall the group differences between primary care and psychiatric populations reiterate the need to recruit subjects from multiple clinical sites to achieve generalizable findings.

This study found that the presence of a lifetime comorbid anxiety disorder was not associated with recurrence or chronicity of major depressive episodes. There was a trend toward an earlier age of onset of depression in subjects with comorbid anxiety. It was not possible in this study to determine the temporal sequence of anxiety and depression in subjects. Future studies may assess whether depression preceded by an anxiety disorder has a different course and outcome from depression with a subsequent anxiety disorder in late life.

The association of poorer social function with comorbid anxiety disorders in our study is consistent with prior reports that panic attacks and phobias are associated with poorer social function in younger adults (33). On the other hand, physical function was not worse in comorbid anxiety disorders, nor was amount of chronic medical illness as measured by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale—Geriatrics. This finding was unexpected, given the association of late-life anxiety disorders with medical illness (34), as well as the findings of a prior study in a mixed-age cohort that showed an interactive effect of increasing age and panic disorder on physical function (35). Our study’s negative finding may be due to the fact that depression is also associated with poorer physical function in the elderly (36). Thus comorbid anxiety disorders may not predict additional physical disability beyond that already associated with depression in the elderly.

We found that comorbid anxiety disorders were associated with increased autonomic symptoms as measured by the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale. This scale measures baseline somatization when used prior to initiation of treatment. Elderly persons may be more likely than younger adults to have somatic symptoms associated with anxiety disorders (34). This finding has clinical importance, because high levels of somatic symptoms during treatment may be misidentified by the patient or clinician as side effects to medication, which could lead to poorer compliance or premature discontinuation of treatment (37). Similarly, in depressed younger adults, those with a comorbid anxiety disorder have also been found to be more likely to have somatic symptoms during treatment and to drop out prematurely (38).

Subjects with comorbid anxiety disorders (other than generalized anxiety disorder) did not have more suicidal ideation. This finding was unexpected, given that prior studies in adults and elderly subjects have found a greater suicide risk in individuals with comorbid panic and depression than in those with either disorder alone (10, 11, 17). The association of comorbidity with greater suicidality should be addressed in longitudinal studies that can examine not only suicidal ideation but also suicide attempts and completed suicides.

A limitation of our study is that a rate for diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder was not available; instead, the rate for symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder was assessed. More than a third of the subjects with major depressive episode also met symptomatic or inclusion criteria for current generalized anxiety disorder. Given the overlap of symptom criteria between major depression and generalized anxiety disorder, this finding could be expected. It has been argued that, because many depressed individuals meet criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, often only during the depressive episodes, the presence of generalized anxiety disorder in a major depressive episode does not warrant a separate diagnosis (6, 39, 40). Rather, it could be viewed as a severity marker (8). Supporting this view, our study found a significant association between severity of depressive symptoms and presence of symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. In addition, however, symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder were independently associated with greater suicidality, even after controlling for severity of depressive symptoms. This finding suggests that symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder have predictive value for patients presenting with depressive disorders. Another clinical study that assessed the presence of symptomatic generalized anxiety disorder in the elderly (41) also found high comorbidity with major depression. In that study, individuals with comorbid symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder had greater functional impairment longitudinally than those with major depression alone, findings that also suggest that symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder predict greater severity in depressed elderly patients.

In conclusion, the study reported here found a high rate of comorbid anxiety disorders in clinical samples of depressed patients. Comorbid anxiety disorders other than generalized anxiety disorder were associated with poorer social function and a higher level of somatic symptoms, while symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder during the depressive episode were associated with greater severity of depressive symptoms, including suicidal ideation. Strengths of the study include the relatively large sample size and the broad representation from multiple clinical settings. A limitation is that the present study is cross-sectional and cannot address the effects of comorbid anxiety disorders on outcomes of depression. Existing longitudinal studies in the depressed elderly (20, 42) suggest that comorbid anxiety is associated with a delayed response to antidepressant medication, a finding also seen in younger adults (43). The question of whether comorbid anxiety disorders predict a different long-term course in the depressed elderly is unresolved (44). Future comorbidity studies in the elderly should address longitudinal outcomes and their implications for treatment, as existing literature suggests a differential course and outcome for these patients.

|

|

Received July 26, 1999; revised Nov. 22, 1999; accepted Nov. 29, 1999. From the Intervention Research Center in Late-Life Mood Disorders, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lenze, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Room E1124, 3811 O’Hara St., Pittsburgh, PA 15213; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-52247, MH-00295, MH-43832, MH-37869, MH-01613, and MH-19986, and National Institute on Aging grant AG-05133. The authors thank the research staff of the Intervention Research Center for Late-Life Mood Disorders for assistance with data collection.

1. Gorman JM: Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depress Anxiety 1996/1997; 4:160–168Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Liu J, Swartz M, Blazer DG: Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1996; 30:8–21Google Scholar

3. Sartorius N, Ustun TB, Lecrubier Y, Wittchen HU: Depression comorbid with anxiety: results from the WHO study on psychological disorders in primary health care. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1996; 30:38–43Medline, Google Scholar

4. Schulberg HC, Madonia MH, Block MR, Coulehan JL, Scott CP, Rodriguez E, Black A: Major depression in primary care practice: clinical characteristics and treatment implications. Psychosomatics 1995; 36:129–137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Clayton PJ, Grove WM, Coryell W, Keller M, Hirschfeld R, Fawcett J: Follow-up and family study of anxious depression. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1512–1517Google Scholar

6. Coryell W, Endicott J, Winokur G: Anxiety syndromes as epiphenomena of primary major depression: outcome and familial psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:100–107Link, Google Scholar

7. Sherbourne CD, Wells KB: Course of depression in patients with comorbid anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord 1997; 43:245–250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Brown C, Schulberg HC, Shear MK: Phenomenology and severity of major depression and comorbid lifetime anxiety disorders in primary medical care practice. Anxiety 1996; 2:210–218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Grunhaus L, Harel Y, Krugler T, Pande AC, Haskett RF: Major depressive disorder and panic disorder: effects of comorbidity on treatment outcome and antidepressant medications. Clin Neuropharmacol 1988; 11:454–461Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Allgulander C, Lavori PW: Causes of death among 936 elderly patients with “pure” anxiety neurosis in Stockholm County, Sweden, and in patients with depressive neurosis or both diagnoses. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34:299–302Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Panic disorder, comorbidity, and suicide attempts. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:805–808Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Manela M, Katona C, Livingston G: How common are the anxiety disorders in old age? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996; 11:65–70Google Scholar

13. Flint AJ: Epidemiology and comorbidity of anxiety disorders in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:640–649Link, Google Scholar

14. Lindesay J, Briggs K, Murphy E: The Guy’s/Age Concern survey: prevalence rates of cognitive impairment, depression and anxiety in an urban elderly community. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 155:317–329Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Ben-Arie O, Swartz L, Dickman BJ: Depression in the elderly living in the community: its presentation and features. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150:169–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Livingston G, Watkin V, Milne B, Manela MV, Katona C: The natural history of depression and the anxiety disorders in older people: the Islington community study. J Affect Disord 1997; 46:255–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Andrade L, Eaton WW, Chilcoat H: Lifetime comorbidity of panic attacks and major depression in a population-based study. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:363–369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Alexopoulos GS: Anxiety-depression syndromes in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1990; 5:351–353Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Parmelee PA, Katz IR, Lawton MP: Anxiety and its association with depression among institutionalized elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1993; 1:46–58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF, Shear MK, Sweet RA, Miller M: Comorbid anxiety disorders in late-life depression. Anxiety 1996; 2:242–247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Nebes R, Miller M, Little JT, Stack J, Houck PR, Bensasi S, Mazumdar S, Reynolds CF: A double-blind randomized comparison of nortriptyline and paroxetine in the treatment of late-life depression: six-week outcome. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 20):16–20Google Scholar

22. Schulberg HC, Mulsant B, Schulz R, Rollman BL, Houck PR, Reynolds CF: Characteristics and course of major depression in older primary care patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998; 28:421–436Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Applied Psychol Measurement 1977; 1:385–401Crossref, Google Scholar

24. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID), Clinician Version: Administration Booklet. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996Google Scholar

25. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Tarlov A, Ware JE, Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Perrin E, Zubkoff M: Medical Outcomes Study: an application of methods for evaluating the results of medical care. JAMA 1989; 262:925–930Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, Rifai AH, Mulsant B, Reynolds CF III: Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res 1992; 41:237–248Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K: The UKU Side Effect Rating Scale: a new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1987; 334:1–100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Cloninger CR: Comorbidity of anxiety and depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 10(3 suppl):43S–46SGoogle Scholar

31. Breslau N: Depressive symptoms, major depression, and generalized anxiety: a comparison of self-reports and results from diagnostic interviews. Psychiatr Res 1985; 15:219–229Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Bromet EJ, Dunn LO, Connell MM, Dew MA, Schulberg HC: Long-term reliability of diagnosing lifetime major depression in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:435–440Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA: The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 11(suppl 3):89–95Google Scholar

34. Palmer BW, Jeste DV, Sheikh JI: Anxiety disorders in the elderly: DSM-IV and other barriers to diagnosis and treatment. J Affect Disord 1997; 46:183–190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Hollifield M, Katon W, Skipper B, Chapman T, Ballenger JC, Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ: Panic disorder and quality of life: variables predictive of functional impairment. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:766–772Link, Google Scholar

36. Bruce ML, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, Blazer DG: The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Am J Public Health 1994; 94:1796–1799Google Scholar

37. Mulsant BH, Pollock B: Treatment-resistant depression in late life. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1998; 11:186–193Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Rollman BL, Block MR, Schulberg HC: Symptoms of major depression and tricyclic side effects in primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 1997; 12:284–291Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Breslau N, Davis GD: Further evidence on the doubtful validity of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Res 1985; 16:177–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Kendler KS: Major depression and generalized anxiety disorder: same genes, (partly) different environments? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:716–722Google Scholar

41. Astrom M: Generalized anxiety disorder in stroke patients: a 3-year longitudinal study. Stroke 1996; 27:270–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Flint AJ, Rifat SL: Anxious depression in elderly patients: response to antidepressant treatment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 5:107–115Medline, Google Scholar

43. Joffe RT, Bagby RM, Levitt A: Anxious and nonanxious depression. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1257–1258Google Scholar

44. Flint AJ, Rifat SL: Two-year outcome of elderly patients with anxious depression. Psychiatry Res 1997; 66:23–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar