Significant Linkage to Compulsive Hoarding on Chromosome 14 in Families With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Results From the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study

Abstract

Objective: Individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) who have compulsive hoarding behavior are clinically different from other OCD-affected individuals. The objective of this study was to determine whether there are chromosomal regions specifically linked to compulsive hoarding behavior in families with obsessive-compulsive disorder. METHODS: The authors used multipoint allele-sharing methods to assess for linkage in 219 multiplex OCD families collected as part of the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. The authors treated compulsive hoarding as the phenotype of interest and also stratified families into those with and without two or more relatives affected with compulsive hoarding. Results: Using compulsive hoarding as the phenotype, there was suggestive linkage to chromosome 14 at marker D14S588 (Kong and Cox logarithm of the odds ratio [LOD] [KAC all =2.9]). In families with two or more hoarding relatives, there was significant linkage of OCD to chromosome 14 at marker C14S1937 (KAC all =3.7), whereas in families with fewer than two hoarding relatives, there was suggestive linkage to chromosome 3 at marker D3S2398 (KAC all =2.9). Conclusions: The findings suggest that a region on chromosome 14 is linked with compulsive hoarding behavior in families with OCD.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a clinically heterogeneous disorder, with considerable variation between patients in the types of obsessions and compulsions they present. There is currently great interest in characterizing individuals with OCD according to their obsessions and compulsions or, alternatively, according to symptom factor or dimensional scores that vary among individuals with the disorder (1) . Clinical features may correlate with course, prognosis, and treatment responsiveness, and it has been hypothesized that different clinical subgroups may be consequences of different etiology and pathogenesis (2) .

To date, the most persuasive evidence for a potentially discrete subtype or dimension of OCD is hoarding behavior. Compulsive hoarding behavior is characterized by the acquisition of, and unwillingness or inability to discard, large quantities of seemingly useless objects that create a significantly cluttered living space and cause considerable distress or impairment in functioning (3) . Hoarding obsessions and compulsions are present in approximately 30% of OCD cases (4 , 5) . As a group, OCD-affected individuals with hoarding symptoms have a more severe illness, greater prevalence of anxiety disorders, and greater prevalence of personality disorders than those without hoarding symptoms (4 – 7) . In addition, OCD patients with hoarding behavior, or with higher scores on a hoarding factor dimension, are often less responsive to treatment with serotonin-reuptake inhibitors or cognitive behavior therapy than OCD patients without hoarding behavior (8 – 11) , although it has also been reported that other types of obsessions and compulsions predict poor treatment response (12) , and results from a more recent treatment trial suggest that OCD patients with hoarding behavior respond as well as other OCD patients (13) . Moreover, results from functional neuroimaging studies suggest that OCD-affected individuals with compulsive hoarding have significantly different levels of activity in specific brain regions compared with other OCD-affected individuals (14 , 15) . Furthermore, family studies have found that first-degree relatives of hoarding probands have a greater prevalence of hoarding behavior than the relatives of nonhoarding probands (5 , 7) as well as strong between-sibling correlations of hoarding factor scores (16) .

We recently reported the results of a genome-wide linkage scan of OCD (17) . In the current analyses, we incorporated hoarding behavior in the linkage analysis of OCD in the families assessed in our previous study. First, we conducted the analyses using compulsive hoarding as the affected phenotype. Second, we stratified the families into those with and without at least two members with compulsive hoarding and conducted separate linkage analyses on each group of families. We hypothesized that hoarding characterizes a genetically distinct subtype of OCD and that there are genomic regions specifically associated with this phenotype.

Method

Ascertainment of Families

The OCD Collaborative Genetics Study, which commenced in 2001, is an ongoing collaboration among investigators at six sites in the United States (Brown University, Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute, Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital, University of California at Los Angeles, and the National Institute of Mental Health). The detailed methods are described elsewhere and summarized below (18) .

The OCD Collaborative Genetics Study targeted families with OCD-affected sibling pairs and extended these when possible through affected first- and second-degree relatives. Individuals were recruited into the study from outpatient and inpatient clinics, referrals from clinicians in the community, websites, media advertisements, self-help groups, and annual meetings of the Obsessive Compulsive Foundation. Family history interviews were conducted to determine that there were at least two OCD-affected siblings in the family who were willing to participate and to identify additional affected relatives. All first- and second-degree relatives were considered for inclusion, and families were extended through the first-degree relatives of all affected cases.

To be considered affected, a participant had to meet DSM-IV OCD diagnostic criteria at any time in his or her life. Probands were included if, in addition to meeting DSM-IV criteria, their first onset of obsessions and/or compulsions occurred before 18 years of age. Probands with schizophrenia, severe mental retardation, Tourette’s syndrome, or secondary OCD (OCD occurring exclusively in the context of depression) were excluded. Participants had to be at least 7 years old to participate in the study. After complete description of the study to the subject, written informed consent (or assent for children) was obtained prior to the clinical interview. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site.

Diagnostic Procedures

Diagnostic assessments were conducted by psychiatrists or Ph.D.-level psychologists experienced with clinical evaluations using the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study Assessment Package, modified and developed for the study, as a semistructured format for the evaluation of psychopathology. The OCD section was adapted from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Lifetime Version Modified for the Study of Anxiety Disorders (19) and included detailed screening questions; the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale for the individual’s worst period of OCD and symptom checklist for obsessions and/or compulsions experienced at any point in the individual’s lifetime (20) and, for each obsession or compulsion present, the age at onset, the amount of time occupied by the symptom, and the level of distress caused by the symptom during the worst period. A similar section was developed for assessing tics, Tourette’s syndrome, and other tic disorders. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (21) was used for assessing other major axis I diagnoses, and a semistructured assessment protocol was used for additional diagnoses of interest. The Family Informant Schedule and Criteria was used to obtain additional information about each participant from a knowledgeable informant (22) . For participants who had received psychiatric treatment, consent was obtained to review relevant medical records and to contact treatment providers, if such information was deemed useful for making diagnoses. Examiners completed a narrative formulation for each subject.

The Johns Hopkins Diagnostic Assignment Checklist was used to collate all the clinical information from the semistructured direct interview, case formulation, informant interview, and medical records. All psychiatric diagnoses were made according to strict DSM-IV criteria. At each site, each subject was reviewed independently by two expert diagnosticians who reviewed all subject data and assigned final best-estimate diagnoses. Final diagnoses were reviewed by diagnosticians at Johns Hopkins University. If all criteria required for having the disorder were met, then a “definite” diagnosis was given. If any required criterion was clearly not met, then the diagnosis was considered “absent.” If it seemed likely that the individual had the diagnosis, but the diagnosticians could not be certain of a given criterion that was required for definite diagnosis, then the diagnosis was made at the “probable” level. If the diagnosticians could not be sure of the presence or absence of a given diagnosis, then that diagnosis was recorded as “unknown.” In the current analyses, only “definite” OCD cases were included as affected in order to minimize potential genetic heterogeneity.

As with other obsessive-compulsive symptoms, hoarding obsessions and compulsions were assessed with the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. To be assigned, these symptoms had to be clinically significant, i.e., the clinician determined that the individual recognized that his or her symptoms were excessive or unreasonable, and the symptoms caused marked distress, were time consuming, or significantly interfered with a normal routine, occupational functioning, or social activities and relationships.

Blood Collection

In most cases, blood was collected from each subject at the time of the diagnostic interview or by the subject’s physician or local phlebotomy laboratory at a later time. Blood samples were collected from all affected probands, their parents, and their affected relatives. If available, blood samples from unaffected relatives were also collected to help determine the phase used for computing identical by decent sharing probabilities. Blood was sent directly to the NIMH Cell Repository at Rutgers University, where Epstein Barr Virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines were created and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extracted. DNA for the genome-wide scan was sent directly to the Center for Inherited Disease Research for genotyping.

Molecular Genotyping

Genotyping was performed at Center for Inherited Disease Research using a modification of the Cooperative Human Linkage Center, version 10 marker set (386 microsatellite markers; average spacing: 9 cM; average heterozygosity: 0.76). The details have been described previously (17) . Family relationships were analyzed using RELCHECK (23) . Misspecified relationships were corrected or removed if there was insufficient information to determine the true relationship. In addition, PedCheck was used for more complicated genotyping error checking for each individual in the data set (24) . Those genotypes with a posterior probability of being incorrect of greater than 75% were removed from the analysis (25) . In addition, we also used the Merlin program to check for Mendelian inconsistencies and to identify genotypes associated with an excessive number of observed recombinations (26) . Marker allele frequencies were computed using data from one individual randomly chosen from each pedigree.

Characteristics of Compulsive Hoarding Cases

In the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study cohort, 999 subjects in 219 families were examined and included in the genome-wide scan; 624 subjects were diagnosed with definite OCD. For the purpose of the current analyses, hoarding was defined as the presence of either hoarding obsessions or hoarding compulsions as assessed during the clinical interview and confirmed in the diagnostic consensus procedure. A total of 389 (62%) of the OCD subjects had neither hoarding obsessions nor compulsions, while 235 (38%) had either or both hoarding obsessions and/or compulsions. Forty-seven percent of the hoarding subjects reported spending at least 1 hour per day occupied with hoarding symptoms, and 64% reported moderate, severe, or extreme distress that was frequent and disturbing. All but six of the hoarding subjects had other obsessions and compulsions in addition to hoarding. The mean age of onset of hoarding symptoms was 14 years (range: 5 to 69 years). Hoarding and nonhoarding participants, respectively, were similar in gender distribution (female: 68% versus 66%, respectively) and age at interview (37 years versus 35 years, respectively) (7) . Of the 219 families included in the genome scan, 74 families had no hoarding individuals, 71 had only one hoarding individual, and 74 had two or more hoarding family members.

Statistical Methods

Multipoint allele-sharing methods were used to assess evidence for linkage by testing the null hypothesis given that the extent of deviation from identical by decent sharing was equal to zero (27) . Using Merlin version 0.10.2 (26) , we computed the Kong and Cox LOD all (KAC all ) statistic for this study. Empirical p values were estimated by simulation under the null hypothesis, using 10,000 or 100,000 replicates with Merlin. In each simulation, the original phenotypes were used, and a new data set, with the same allele frequencies, marker order, genetic distances between markers, as well as missing-data patterns, was generated. Therefore, “significant signals” obtained through simulation are chance findings. Intuitively, when the simulation-derived p values are lower, the probability of observing a false positive KAC LOD score is smaller.

We conducted two types of statistical analyses. First, we tested for linkage using compulsive hoarding as the phenotype. Second, we stratified families a priori into those having two or more family members with compulsive hoarding (74 families) and those having zero members or one member with compulsive hoarding (145 families) and tested for linkage using OCD as the phenotype.

Results

Analyses Based on Compulsive Hoarding as the Phenotype

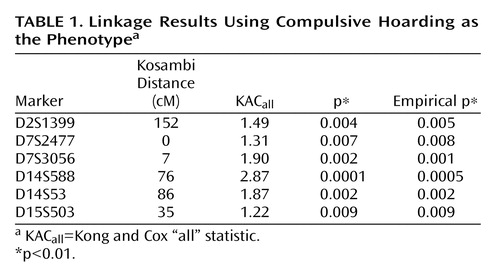

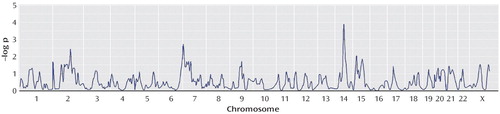

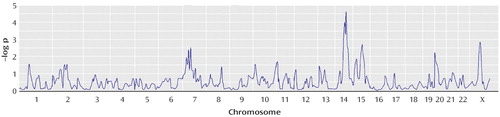

There was a strong linkage signal on chromosome 14 (at marker D14S588: KAC all =2.87, p=0.0001; and adjacent marker D14S53: KAC all =1.87, p=0.002). There also were signals on chromosome 7 (at marker D7S3056: KAC all =1.90, p=0.002; and adjacent marker D7S2477: KAC all =1.31, p=0.007) and chromosome 2 (at marker D2S1399: KAC all =1.49, p=0.004), as well as on chromosome 15 (at marker D15S503: KAC all =1.22, p=0.009) ( Figure 1 and Table 1 ).

Analyses Based on Stratification of Families

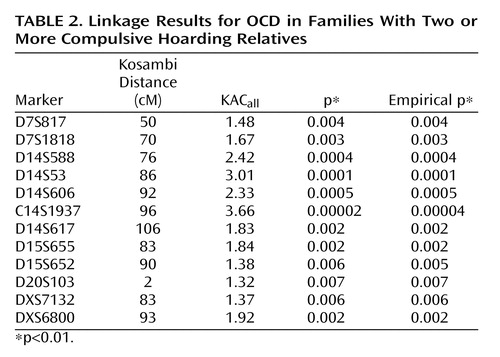

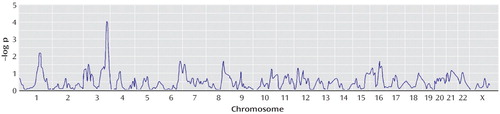

The linkage findings were different between the two groups of families in several genomic regions. In the families with two or more hoarding relatives, there was a strong signal on chromosome 14 (at marker C14S1937: KAC all =3.66, p=0.00002); the linkage peak spans a distance of approximately 40 cM. In addition, there was a signal on chromosome 7 (at marker D7S1818: KAC all =1.67, p=0.003; and adjacent marker D7S817: KAC all =1.48, p=0.004). There also was a signal on chromosome X (at marker DXS6800: KAC all =1.92, p=0.002; and adjacent marker DXS7132: KAC all =1.37, p=0.006). There were additional signals on chromosome 15 (at marker D15S655: KAC all =1.84, p=0.002; and adjacent marker D15S652: KAC all =1.38, p=0.006) and chromosome 20 (at marker D20S103: KAC all =1.32, p=0.007) ( Figure 2 and Table 2 ).

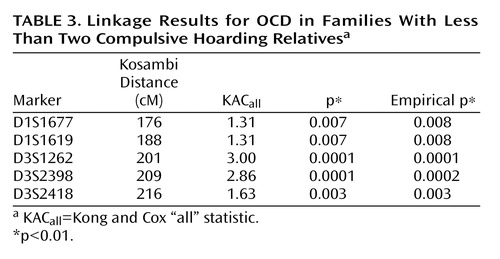

In the families with zero or one hoarding relative, there was a strong signal on chromosome 3 at marker D3S1262 (KAC all =3.00, p=0.0001) and adjacent marker D3S2398 (KAC all =2.86, p=0.0001) and marker D3S2418 (KAC all =1.63, p=0.003). There also were signals on chromosome 1 at marker D1S1677 (KAC all =1.31, p=0.007) and the adjacent marker D1S1619 (KAC all =1.31, p=0.007) ( Figure 3 and Table 3 ).

Discussion

Over the past two decades, evidence for the familial aggregation of OCD has been reported from family studies (28 – 31) , and segregation analyses support the contribution of major genes with dominant or codominant transmission (32 , 33) . Two genome-wide linkage scans of OCD have been reported to date. In a study of seven large OCD pedigrees with pediatric OCD probands and at least two affected relatives, the strongest linkage finding was on chromosome 9p24, with a dominant parametric LOD score of 1.97 after fine mapping of the region (34) . Recently, Shugart et al. (17) reported the results of a genome-wide linkage scan of families collected as part of the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Linkage signals were detected by multipoint analysis on chromosomes 3q27-28 (p=0.0002), 6q (p=0.003), 7p (p=0.001), 1q (p=0.003), and 15q (p=0.006).

OCD is thought to be a complex disorder that is etiologically heterogeneous. The current study utilized the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study genotype data to investigate the possible genetic etiology of the compulsive hoarding phenotype. Based on prior findings that hoarding behavior might characterize a clinical subtype of OCD (1 – 11 , 14 , 15) and aggregates in OCD-affected families (5 , 7 , 16) , we hypothesized that using compulsive hoarding as the phenotype of interest in a genome-wide linkage scan might reduce genetic heterogeneity and lead to stronger evidence of linkage. Considering only those subjects who had the compulsive hoarding phenotype as affected, we found evidence of “suggestive” linkage to a region of chromosome 14 (KAC all =2.87, p=0.0001), according to the guidelines of Kruglyak and Lander (35) . Other signals on chromosomes 2, 7, and 15 are not considered suggestive using these guidelines.

We also hypothesized that the likelihood of finding genetic linkage would be greater in families having multiple individuals with hoarding, i.e., presumably having a greater “genetic loading” for hoarding, whereas, in families have zero or one hoarding relative, OCD would be linked to other genetic regions. This stratification approach of using clinical features to attempt to create more homogeneous groups has been used in genetic linkage studies of other complex disorders (36) . Using this approach, we found evidence for “significant” linkage of OCD to chromosome 14 (KAC all =3.66, p=0.00002) in the families with two or more hoarding relatives, whereas there was evidence of “suggestive” linkage to chromosome 3 (KAC all =2.9, p=0.0001) in the families with fewer than two hoarding individuals. Interestingly, whereas linkage to chromosome 3 was found in the initial scan by Shugart et al. (17) , the strong linkage findings on chromosome 14 emerged only when hoarding was included, either in the phenotypic definition or in stratification of families.

Several potential limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, we recognize that the power of detecting a linkage signal was limited in the presence of heterogeneity, and the results need to be replicated in a larger cohort. Power analyses indicated that we would need twice the number of families to detect linkage with compulsive hoarding as the phenotype, if the level of heterogeneity were as high as 50%. Second, the location of the peaks on chromosome 14 using the two different methods is 20 cM apart. They could be the same peak, within a margin of chance variation, or they could represent two distinct genetic signals. As for other presumably complex phenotypes, additional analyses of the hoarding trait with a larger number of families and denser set of markers would be important for determining whether these peaks arise from the same or different susceptibility loci (37) . Third, although we used hoarding behavior to define more homogeneous groups, we recognize that several clinical characteristics distinguish hoarding from nonhoarding individuals, such as greater prevalence of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive personality features, and difficulty making decisions (4 – 7) . Therefore, the chromosomal regions identified in this study may be linked to some of these other features rather than or in addition to hoarding behavior.

We analyzed hoarding OCD as a binary trait, although results from factor analysis suggest that hoarding may be construed dimensionally (1 , 16) . If so, treating hoarding as a quantitative trait may provide greater power to detect linkage. In a genome scan of hoarding in 77 sibling pairs concordant for Tourette’s syndrome, Zhang et al. (38) found evidence for linkage to three regions (4q, 5q, and 17q) when hoarding was treated as either a quantitative or binary trait (38) . These linkage regions are different than the ones found in our study, which may be a reflection of the differences in family selection criteria. Whereas the Zhang et al. analyses were of families obtained through Tourette’s syndrome patients and with two or more siblings with Tourette’s syndrome, the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study cohort consisted of multiplex OCD families, most of whom had two or more OCD-affected sibling pairs, obtained through probands with OCD who did not have Tourette’s syndrome.

Hoarding behavior can occur in other conditions, such as Prader-Willi syndrome (39) and velocardiofacial syndrome (40) . We suspect that hoarding behavior itself is heterogeneous, and that the etiology of hoarding behavior is different in various syndromes. Whether compulsive hoarding should be construed as a clinical characteristic of OCD or a syndrome distinct from OCD is an important contemporary diagnostic question. Moreover, hoarding behavior is a major community and public health problem in its own right, and elucidation of its etiology is important. We plan to further investigate the chromosome 14 linkage region using high-density mapping and including additional families. Identifying genes in this region may help to clarify the pathophysiology of compulsive hoarding and to develop more effective treatments for this behavior.

1. Mataix-Cols D, Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF: A multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:228–238Google Scholar

2. Miguel EC, Leckman JF, Rauch S, Rosario-Campos MC, Hounie AG, Mercadante MT, Chacon P, Pauls DL: Obsessive-compulsive disorder phenotypes: implications for genetic studies. Mol Psychiatry 2005; 10:258–275Google Scholar

3. Frost RO, Hartl TL: A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther 1996; 34:341–350Google Scholar

4. Frost RO, Krause MS, Steketee G: Hoarding and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Behav Modif 1996; 20:116–132Google Scholar

5. Samuels J, Bienvenu OJ, Riddle MA, Cullen BAM, Grados MA, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Nestadt G: Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from a case-control study. Behav Res Ther 2002; 40:517–528Google Scholar

6. Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams LF, Warren R: Mood, personality disorder symptoms and disability in obsessive compulsive hoarders: a comparison with clinical and nonclinical controls. Behav Res Ther 2000; 38:1071–1081Google Scholar

7. Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ III, Pinto A, Fyer AJ, McCracken JT, Rauch SL, Murphy DL, Grados MA, Greenberg BD, Knowles JA, Piacentini J, Cannistraro PA, Cullen B, Riddle MA, Rasmussen SA, Pauls DL, Willour VL, Shugart YY, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Nestadt G: Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Behav Res Ther (in press)Google Scholar

8. Black DW, Monahan P, Gable J, Blum N, Clancy G, Baker P: Hoarding and treatment response in 38 nondepressed subjects with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:420–425Google Scholar

9. Mataix-Cols D, Rauch SL, Manzo PA, Jenike MA: Use of factor-analyzed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1409–1416Google Scholar

10. Mataix-Cols D, Marks IM, Greist JH, Kobak KA, Baer L: Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions as predictors of compliance with and response to behaviour therapy: results from a controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2002; 71:255–262Google Scholar

11. Saxena S, Maidment KM, Vapnik T, Golden G, Rishwain T, Rosen RM, Tarlow G, Bystritsky A: Obsessive-compulsive hoarding: symptom severity and response to multimodal treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:21–27Google Scholar

12. Shetti CN, Reddy YC, Kandavel T, Kashyap K, Singisetti S, Hiremath AS, Siddequehusen MU, Raghunandanan S: Clinical predictors of drug nonresponse in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:1517–1523Google Scholar

13. Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, Baxter LR: Paroxetine treatment of compulsive hoarding. J Psychiatr Res (in press)Google Scholar

14. Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, Smith EC, Zohrabi N, Katz E, Baker SK, Baxter LR Jr: Cerebral glucose metabolism in obsessive-compulsive hoarding. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1038–1048Google Scholar

15. Mataix-Cols D, Wooderson S, Lawrence N, Brammer MJ, Speckens A, Phillips ML: Distinct neural correlates of washing, checking, and hoarding symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:564–576Google Scholar

16. Hasler G, Pinto A, Greenberg BD, Samuels J, Fyer AJ, Pauls D, Knowles JA, McCracken JT, Piacentini J, Riddle MA, Rauch SL, Rasmussen SA, Willour VL, Grados MA, Cullen B, Bienvenu OJ, Shugart YY, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Wang Y, Ronquillo J, Nestadt G, Murphy DL: Familiality of factor analysis-derived YBOCS dimensions in OCD affected sibling pairs from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Biol Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

17. Shugart YY, Samuels J, Willour VL, Grados MA, Greenberg BD, Knowles JA, McCracken JT, Rauch SL, Murphy DL, Wang Y, Pinto A, Fyer AJ, Piacentini J, Pauls DL, Cullen B, Page J, Rasmussen SR, Bienvenu OJ, Hoehn-Saric R, Valle D, Liang KY, Riddle MA, Nestadt G: Genome-wide linkage scan for obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence for susceptibility loci on chromosomes 3q, 7p, 15q, 6q, and 1q. Mol Psychiatry 2006; 11:763–770Google Scholar

18. Samuels JF, Riddle MA, Greenberg BD, Fyer AJ, McCracken JT, Rauch SL, Murphy DL, Grados MA, Pinto A, Knowles JA, Piacentini J, Cannistraro PA, Cullen B, Bienvenu OJ III, Rasmussen SA, Pauls DL, Willour VL, Shugart YY, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Nestadt G: The OCD Collaborative Genetics Study: methods and sample description. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2006; 141:201–207Google Scholar

19. Fyer AJ, Mannuzza SM, Schleyer B, Aaronson C, Klein DF, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia: Lifetime Anxiety Version, revised ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1991Google Scholar

20. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006–1011Google Scholar

21. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

22. Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ, Endicott J, Klein DF: Family Informant Schedule and Criteria. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1985Google Scholar

23. Broman KW, Weber JL: Estimation of pairwise relationships in the presence of genotyping errors. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 63:259–266Google Scholar

24. O’Connell JR, Weeks DE: PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 63:259–266Google Scholar

25. Douglas JA, Skol AD, Boehnke M: Probability of detection of genotyping errors and mutations as inheritance inconsistencies in nuclear-family data. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 70:487–495Google Scholar

26. Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR: Merlin-rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet 2002; 30:97–101Google Scholar

27. Kong A, Cox NJ: Allele-sharing models: LOD scores and accurate linkage tests. Am J Hum Genet 1997; 61:1179–1188Google Scholar

28. Black DW, Noyes R Jr, Goldstein RB, Blum N: A family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:362–368Google Scholar

29. Pauls DL, Alsobrook JP, Goodman W, Rasmussen S, Leckman JF: A family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:76–84Google Scholar

30. Nestadt G, Samuels J, Riddle M, Bienvenu OJ, Liang KY, LaBuda M, Walkup J, Grados M, Hoehn-Saric R: A family study of obsessive compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:358–363Google Scholar

31. Hanna GL, Himle JA, Curtis GC, Gillespie BW: A family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder with pediatric probands. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2005; 34:13–19Google Scholar

32. Nestadt G, Lan T, Samuels J, Riddle M, Bienvenu OJ, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Cullen B, Grados M, Beaty TH, Shugart YY: Complex segregation analysis provides compelling evidence for a major gene underlying obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and heterogeneity by gender. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 67:1611–1616Google Scholar

33. Hanna GL, Fingerlin TE, Himle JA, Boehnke M: Complex segregation analysis of obsessive-compulsive disorder in families with pediatric probands. Hum Hered 2005; 60:1–9Google Scholar

34. Hanna GL, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Cox NJ, Boehnke M, Himle JA, Curtis GC, Leventhal BL, Cook EH Jr: Genome-wide linkage analysis of families with obsessive-compulsive disorder ascertained through pediatric probands. Am J Med Genet 2002; 114:541–552Google Scholar

35. Kruglyak L, Lander ES: High-resolution genetic mapping of complex traits. Am J Hum Genet 1995; 56:1212–1223Google Scholar

36. Pulver AE, Mulle J, Nestadt G, Swartz KL, Blouin JL, Dombroski B, Liang KY, Housman DE, Kazazian HH, Antonarakis SE, Lasseter VK, Wolyniec PS, Thornquist MH, McGrath JA: Genetic heterogeneity in schizophrenia: stratification of genome scan data using co-segregating related phenotypes. Mol Psychiatry 2000; 5:650–653Google Scholar

37. Roberts SB, MacLean CJ, Neale MC, Eaves LJ, Kendler KS: Replication of linkage studies of complex traits: an examination of variation in location estimates. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 65:876–884Google Scholar

38. Zhang H, Leckman JF, Pauls DL, Tsai CP, Kidd KK, Campos MR: Tourette Syndrome Association International Consortium for Genetics: genomewide scan of hoarding in sib pairs in which both sibs have Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 70:896–904Google Scholar

39. Dykens E, Shah B: Psychiatric disorders in Prader-Willi syndrome. CNS Drugs 2003; 17:167–178Google Scholar

40. Gothelf D, Presburger G, Zohar AH, Burg M, Nahmani A, Frydman M, Shohat M, Inbar D, Aviram-Goldring A, Yeshaya J, Steinberg T, Finkelstein Y, Frisch A, Weizman A, Apter A: Obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with velocardiofacial (22q11 deletion) syndrome. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2004; 126:99–105Google Scholar