Early Postpartum Mood as a Risk Factor for Postnatal Depression in Nigerian Women

Abstract

Objective: This report explored early postpartum mood changes and their correlation with postnatal depression in African women. Method: Scores on the Maternity Blues Scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for 478 women on the fifth day postpartum were compared with the women’s Research Diagnostic Criteria diagnosis at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum. Results: The Maternity Blues Scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores at day 5 postpartum were found to reliably predict the diagnosis of depression at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum. Conclusions: African women at risk of postnatal depression can be identified in the early postnatal period by incorporating simple screening methods.

Postnatal depression is one of the most common forms of psychiatric morbidity of childbearing and affects 10%–15% of postpartum women in Western culture (1) . It has long-lasting adverse effects on the emotional and cognitive development of the children of affected women (2) .

Although postnatal depression is amenable to treatment, evidence shows that more than 50% of all cases are undetected in primary care settings (3) . Studies, however, have suggested that mothers at risk of postnatal depression may be identified early in the postpartum period, such that secondary preventive interventions may be implemented (4 – 6) .

In Africa, where medical personnel and psychiatrists are scarce, simple identification of depressed mothers in the early postpartum period is necessary. A review of the literature found no study performed on maternal mood in the early postpartum period or its relationship to postnatal depression. The aims of this study were to carry out a prospective survey of the incidence of early postpartum mood change and its correlation with postnatal depression in a group of Nigerian women. It also aimed to assess the usefulness of a screening instrument for use in the early postpartum period.

Method

Between January and June 2004, 586 women in five participating health centers in Ilesa Township were consecutively recruited for the study on the first day after their delivery. Excluded were women who delivered by cesarean section, were critically ill, did not speak the local Yoruba language or English, did not reside in Ilesa Township, or were unable to give informed consent.

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants after the aims and objectives of the study had been explained. The ethics and research committees of the hospitals approved the study protocol. On each of the first 5 days after delivery, the mothers completed the Maternity Blues Scale, a self-rated scale composed of 13 symptoms (7) . The sum of all 13 symptom scores provided the daily scores, with a range of 0 to 26. Women scoring 8 or above 1 or more days after delivery were considered to have “the maternity blues.” The scores on the fifth day were used in this analysis.

On the fifth day, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (8) was also completed (5-day Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale is a 10-item self-report questionnaire. Each question has four stem questions that are scored 0–3 (resulting range=0–30). In Nigeria, cutoffs of 9 and 13 have been recommended for symptoms of minor and major depression, respectively (9) . The Yoruba translation of both the Maternity Blues Scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale were performed by two sets of psychiatrists and linguists. Most of the postpartum women were discharged 72 hours after delivery. Research assistants contacted them at home for the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and the rest of the Maternity Blues Scale assessments.

At the end of postnatal weeks 4 and 8, two trained psychiatrists, using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (10) , assessed the present psychiatric states of all the women with a face-to-face interview. The SADS is designed to obtain data to formulate a diagnosis based on the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC). Both major and minor depression were considered positive diagnoses of depression. At these periods, the mothers also completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (4-week Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and 8-week Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores). Sociodemographic characteristics were collected from their case notes.

The participants were classified as cases or noncases based on their RDC diagnoses. The reliability of the RDC diagnoses by the two psychiatrists was evaluated by using kappa analysis. Group differences were calculated by using independent-sample t tests and Pearson’s chi-square tests. All tests were two-tailed, and the level of significance was p<0.05. Spearman’s coefficient was used for the correlations.

Results

Of the 582 women recruited, 478 (82%) had completed the study at 8 weeks postpartum. The mean age of the subjects was 28.48 years (SD=12.19). The interrater reliability between the two psychiatrist clinical interviews was 0.86, measured with Cohen’s kappa. The mean Maternity Blues Scale score at day 5 was 6.37 (SD=5.22), and the mean Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score at day 5 was 5.88 (SD=5.82). The 4-week Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score was 3.97 (SD=3.55), and the 8-week Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score was 4.18 (SD=4.02).

On the fifth postpartum day, 146 (30.5%) of the women were identified as experiencing “maternity blues.” Their 5-day Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores identified 100 (20.9%) of the women as having depressive symptoms. The correlation between their Maternity Blues Scale and 5-day Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores was 0.69 (p<0.001).

At 4 and 8 weeks postpartum, the prevalence of depression, as assessed by the SADS, was 10.7% and 16.3%, respectively. The correlation between Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores and RDC diagnoses at the 4th week postpartum was 0.89 (p<0.001), and at the 8th week, it was 0.92 (p<0.001). With the receiver -operating characteristic curve, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score at the 4th week postpartum had a sensitivity of 0.96 and a specificity of 0.92 at a cutoff between 8 and 9, with an area under the curve of 0.98. At the 8th week postpartum, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale had a sensitivity of 0.90 and a specificity of 0.89 at the cutoff between 8 and 9, with an area under the curve of 0.94.

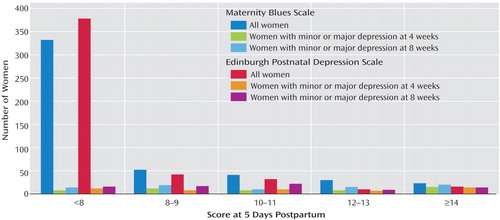

Scores on the Maternity Blues Scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at day 5 postpartum were found to reliably predict the diagnosis of depression at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum. Of the 146 women with “maternity blues,” 43 (29.5%) and 64 (43.8%) were diagnosed as depressed at 4 weeks and 8 weeks postpartum, respectively. Of the women not classified as having “maternity blues,” eight (2.4%) and 14 (4.2%) were diagnosed as depressed at 4 weeks and 8 weeks postpartum, respectively; 39% and 62% of the women scoring more than 8 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at day 5 were diagnosed to be depressed at 4 weeks and 8 weeks, respectively. Of the women scoring more than 12 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale on day 5, 21 (80.8%) and 23 (88.5%) were diagnosed as having depression at 4 weeks and 8 weeks, respectively. Figure 1 shows the frequencies of RDC diagnoses of depression (major and minor depression) at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum as functions of the Maternity Blues Scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale administered 5 days postpartum.

Discussion

This study clearly demonstrates a strong relationship between maternal mood on day 5, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks postpartum. Women classified as having “maternity blues” are 12 times more likely to be diagnosed as depressed at 4 weeks and 10 times more likely to be diagnosed as depressed at 8 weeks postpartum than those not classified as having “the blues.” Women scoring more than 8 points 5 days postpartum on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale are also 12 times and 14 times more likely to be diagnosed as depressed at 4 weeks and 8 weeks postpartum, respectively, as women scoring 8 or below. Those scoring higher than 12 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at 5 days postpartum are nine and six times more likely to be diagnosed as depressed at 4 weeks and 8 weeks postpartum, respectively.

It should be noted, however, that the depressed women might have had the onset of their depression during pregnancy, which was not addressed in this study. The diagnostic evaluation of depression was delayed in this study so as not to miss later-onset cases of depression.

Other authors in Western culture have demonstrated a link between early maternal mood and postnatal depression (4 – 6) ; our study affirms that these findings are applicable to African women, despite the cultural differences. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, because of its brevity and higher sensitivity and specificity, is recommended as a single screening tool for depression in the early postpartum period. It will definitely help in the early detection and prompt treatment of postnatal depression.

1. O’Hara MW, Swain AM: Rates and risk of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996; 8:37–54Google Scholar

2. Weinberg MK, Tronick EZ: The impact of maternal psychiatric illness on infant development. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 2):53–61Google Scholar

3. Briscoe M: Identification of emotional problems in postpartum women by health visitors. Br Med J 1986; 292:1245–1247Google Scholar

4. Teissedre F, Chabrol H: Detecting women at risk of postnatal depression using the EPDS at 2 to 3 days postpartum. Can J Psychiatry 2004; 49:51–54Google Scholar

5. Hannah P, Adams D, Lee A, Glover V, Sadler M: Links between early postpartum mood and postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160:777–780Google Scholar

6. Yamashita H, Yoshida K, Nakano H, Tashino N: Postnatal depression in Japanese women: detecting the early onset of postnatal depression by closely monitoring the postpartum mood. J Affect Disord 2004; 78:163–169Google Scholar

7. Stein G: The pattern of mental change and body weight change in the first postpartum week. J Psychosom Res 1980; 24:165–171Google Scholar

8. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky RV: Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150:782–786Google Scholar

9. Uwakwe R, Okonwo JE: Affective (depressive) morbidity in puerperal Nigerian women: validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003; 107:251–259Google Scholar

10. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS), 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1979Google Scholar