A Clinical Approach to Mild Cognitive Impairment

A 70-year-old woman presented with memory decline that had progressed gradually over 12–15 months and was manifested by her repeating statements and questions, frequently losing items, and forgetting things. For example, on returning from an out-of-town visit to her brother, she had difficulty remembering what her own house looked like. She had lent money to her brother and was sure he had paid her back, although he had not. She had trouble recalling recent conversations. When shopping, she would purchase unnecessary items because she was not sure what she already had purchased. According to her husband, she was not as patient as usual but had no problems with mood, sleep, appetite, interpersonal relationships, or activities of daily living and continued to work part-time as a substitute teacher. Family history, medical history, neurological examination, and general mental status examination were unremarkable. She was rated independent on scales filled out by her husband for activities of daily living. Her score on the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia was 5 (normal), and she scored 26 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), losing 3 points on short-term recall and 1 point on orientation. Laboratory studies were unremarkable. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed mild cortical atrophy consistent with age and an old left internal capsule infarct. Neuropsychological testing showed normal functioning on language, attention, visuospatial, and executive function tests. However, she had moderate impairment in immediate and delayed memory on both verbal and visual memory tests and mild impairment on the Trail Making Test part B, a test of executive function. What is the diagnosis? Is this patient developing dementia? What medications or life style changes might help prevent dementia? Is depression a cause of dementia, a reaction to dementia, or both?

Clinical Presentation of Mild Cognitive Impairment

This vignette illustrates several of the issues involved in the clinical care of patients with mild cognitive impairment. The patient was functioning quite well day-to-day, continued to work as a teacher, and had not restricted any of her activities. Over the past year she was having difficulties primarily with memory, leading to some frustration and conflict with her husband. While her husband did not perceive this as a problem—in fact, he believed that it was simply age-related forgetfulness—she was very concerned that something was wrong with her cognition. On formal cognitive assessment in neuropsychological testing, she had notably impaired memory functioning and slightly impaired executive functioning.

This patient meets current diagnostic criteria for amnestic mild cognitive impairment (see below) and is at high risk of progression to dementia in the near term (3–5 years). Patients often have a family history of dementia and present out of concern that their memory loss is evidence of an onset of the condition that afflicted their relative. Given an aging population and increasing media attention and public awareness of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of cognitive impairment, psychiatrists and clinicians in related fields will see an increasing number of such patients in the coming years (1) .

The purpose of this article is to describe presentations of mild cognitive impairment that psychiatrists might see in practice and the relationship of this disorder with other psychiatric disturbances; to update readers on the history, phenomenology, diagnosis, and evaluation of patients with mild cognitive impairment; and to provide practical recommendations for management and treatment.

Brief Historical Background

The observation that some older persons become mildly forgetful dates back to the earliest medical writings. More recently, in the first epidemiologic studies of dementia carried out in Europe, a group of individuals was identified who did not fit clearly into the cognitively normal group or the dementia group (2) . During follow-up study of these individuals, more than one-third progressed to dementia over several years, while the others continued to show memory and other impairments that did not progress. This observation, later confirmed in other studies, led to efforts to better understand this group whose cognitive functioning falls between “normal for age and education” and dementia.

Several terms emerged to describe this group, reflecting reasoning about the cause of the cognitive impairment, including “benign senescent forgetfulness” and “age-associated memory impairment”—both of which suggest that many of these individuals are exhibiting normal age-related changes. These terms were soon recognized as inadequate, however. By the early 1980s it was clear that many individuals in this group are exhibiting a prodromal syndrome of Alzheimer’s dementia. Moreover, clinicians have noted for years that dementia patients and their families retrospectively report deficits in memory or executive function that started several years before evaluation.

Thus, this in-between group, whose impairment is sometimes called “cognitive impairment not dementia” (3) , might be subdivided into individuals with memory loss that is age related, and in that sense benign, and those whose memory or other cognitive symptoms are the first clinical manifestations of Alzheimer’s or another dementia. The group thought to be in the prodromal stages of Alzheimer’s disease is now said to have “mild cognitive impairment” (4) . The term “vascular cognitive impairment” has been proposed to refer to the prodrome of vascular dementia. Although currently available treatments for Alzheimer’s disease are not effective in altering its course, mild cognitive impairment may prove to be a better target for emerging neuroprotective treatments.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of cognitive impairment not dementia varies according to how narrowly one defines the syndrome, with age-associated memory impairment being broadest and mild cognitive impairment narrowest (5) . Estimates of the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment range from 3% to 53% and are generally about twice those of dementia (6) . One of the most robust estimates, based on a population-based sample, places the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment at 19% among persons over 75 years of age (7) . Incidence rates of mild cognitive impairment are estimated at 1%–1.5% annually in this age range, with depressive symptoms, increasing age, and less education reported as risk factors (8) . Prevalence estimates of cognitive impairment not dementia, a broader diagnostic category, range from 15% to 30%.

Criteria, Definition, and Subtypes of Mild Cognitive Impairment

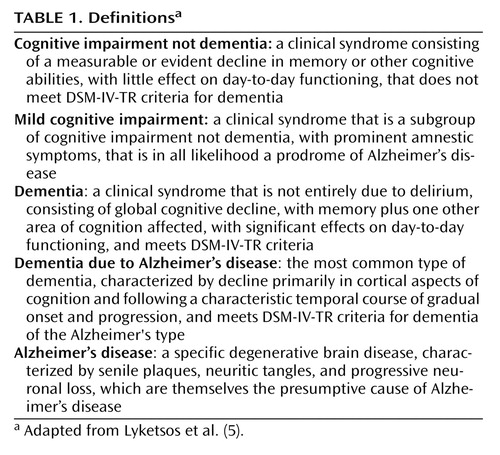

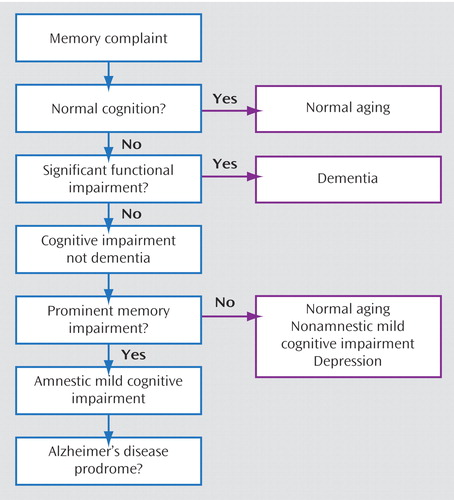

Table 1 presents some basic definitions, and Figure 1 presents a diagnostic flowchart for mild cognitive impairment. There is an evolving consensus that the patient with mild cognitive impairment is neither normal nor demented and has subjective cognitive complaints and objective evidence of cognitive deficits (9 , 10) . Mild cognitive impairment has been further subtyped as amnestic (having memory deficits) or nonamnestic and involving single or multiple cognitive domains. For example, a patient whose only cognitive complaint is memory deficits would be categorized as having “amnestic mild cognitive impairment, single domain.” A patient with memory deficits and additional complaints of difficulties in nonmemory cognitive domains—for example, problem solving (executive function) or word finding (expressive language)—would be categorized as having “amnestic mild cognitive impairment, multiple domain.” If there is no memory complaint but there are complaints in nonmemory cognitive domains, the patient would be categorized as having “nonamnestic mild cognitive impairment,” which could similarly be single or multiple domain (see reference 10 for review of these subtypes).

The diagnosis and prognosis of amnestic mild cognitive impairment is the most thoroughly studied of these subtypes. It is frequently a prodrome to Alzheimer’s disease, whereas the prognostic significance of other subtypes of mild cognitive impairment is not as well understood. Diagnostic criteria have been validated and operationalized to identify patients in this at-risk group (11) .

In mild cognitive impairment, patients do not have significant functional deficits; the presence of functional deficits suggests instead a diagnosis of dementia. In evaluating functional deficits, the judgment of the clinician, integrating patient and caregiver reports, is essential. Unlike cognitive impairment, which can be assessed by neuropsychological testing, the judgment of whether a patient’s social and occupational functioning are generally preserved does not lend itself to operationalization in a single instrument. Longitudinal studies have shown that clinicians’ judgments are surprisingly valid, accurate, and predictive of prognosis (12) .

Office Diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment

History

The most important aspect of history taking when evaluating a patient for mild cognitive impairment is to identify any significant functional deficits, which would point instead to a diagnosis of dementia. The definition of mild cognitive impairment allows for minimal changes in occupational, social, or leisure functioning. We propose defining significant functional deficits as those affecting instrumental activities of daily living to an extent that the patient has to give up a function and someone else (typically a caregiver) has to assume it for the patient to remain stable in his or her current social-occupational environment. Relevant instrumental activities of daily living vary according to stages of the life cycle and may include the ability to hold a job, plan new enterprises, maintain long-standing hobbies or start new ones, function as a parent or grandparent, pay bills and record payments, perform housework or home maintenance, organize and participate in social activities, and so on. Interviewing a family member or close friend is often essential in ascertaining whether significant functional deficits are present. The patient described in the opening vignette demonstrates the challenges of assessing function: she has symptoms and signs of impairment in short-term recall and executive function but only subtle deficits in daily life that do not support a diagnosis of dementia. If a patient has significant functional deficits and the cognitive impairment is global, affecting memory plus one other area of cognition, the diagnosis is dementia and not mild cognitive impairment.

The patient in the vignette was anxious and frustrated with her symptoms, a common complaint in patients with mild cognitive impairment. The symptoms of depression in mild cognitive impairment often differ from those in cognitively intact individuals. Anxiety and irritability are often more prominent than mood change per se, and mood change is often attributed to the patients’ and families’ worry that the patient might be developing Alzheimer’s disease. It is important to differentiate mood symptoms that are a reaction to cognitive deficits (and may be transient) from sustained mood changes that may further affect function. Likewise, the symptoms of depression in Alzheimer’s disease differ from those in cognitively intact individuals, and symptoms of depression in mild cognitive impairment may be part of the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum (13) . However, marked changes in personality, including prominent disinhibition, loss of social skills, inappropriate sexual behavior, cursing, irritability, or apathy, may point to prodromal frontotemporal dementia, particularly if the patient is younger (<70 years).

Mental Status Examination

Special attention should be paid to signs of anxiety, depression, inattention, and disinhibition during the examination. The clinician should be particularly alert to restlessness or agitation, which can accompany late-life depression, as well as negative self-statements, poor effort, and tearfulness. A degree of tearfulness congruent with that of the dysphoria evident during the clinical interview and accompanied by negative self-statements or expressions of hopelessness might support a predominance of depressive symptomatology, and a trial of antidepressant treatment would be indicated before further cognitive evaluation can be done.

The MMSE, although widely used, is probably not sensitive or specific enough for a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment; one study showed a 70% sensitivity and specificity using a cutoff of 26 or less for cognitive impairment (14) . The addition of recall tasks with a longer delay than on the MMSE increased sensitivity and specificity to >80%, and tools such as the Modified Mini-Mental State examination may be more useful (15) . Other useful tests include the clock drawing test, which is sensitive for detecting early deficits in visuoconstructional functioning; the Frontal Assessment Battery (16) ; and mental alternation, which is particularly useful for detecting early symptoms of frontotemporal dementia.

Neuropsychological testing is helpful but not definitive for the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. Typical cognitive domains tested and commonly used tests include delayed episodic verbal and logical recall (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, Wechsler Memory Delayed Recall); verbal category and semantic fluency (animals, words beginning with F-A-S); attention (digit span, forward and backward); processing speed (Trail Making Test part A); visuoconstructional function (clock drawing test, Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test); executive functioning (Trail Making Test part B, symbol-digit substitution). A typical battery of neuropsychological instruments assessing these cognitive domains is more sensitive than routine office tests and can provide a more thorough profile of deficits, allowing for distinctions between amnestic and nonamnestic, and single- and multiple-domain, mild cognitive impairment.

Computerized neuropsychological screening offers a time- and cost-efficient alternative to traditional neuropsychological testing and may be especially useful for diagnosing mild cognitive impairment. A variety of computerized batteries are available, with varied evidence for reliability and validity, and as the evidence becomes more robust, such tools may become more widely used in geropsychiatric practice.

Diagnostic Tests

We recommend a laboratory workup for amnestic mild cognitive impairment but not for syndromes that are less likely to be dementia prodromes, such as cognitive impairment not dementia or age-associated memory impairment. Medical syndromes that can cause cognitive impairment include metabolic abnormalities (hypernatremia, hypoglycemia, hypercalcemia, uremia, hypothyroidism, liver failure), infection, and vitamin deficiencies (notably B 12 deficiency, which is relatively common in older persons because of poor absorption due to achlorhydria). Thus, a complete metabolic workup, CBC, thyroid function tests, and vitamin B 12 level are indicated. CSF studies are rarely needed unless CNS infection is suspected clinically—for example, because of meningeal signs, HIV seropositivity, positive syphilis screen, or a new seizure disorder. However, decreased CSF β-amyloid protein and increased phosphorylated tau have good sensitivity and specificity in predicting transition from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s dementia (17) and may prove to be useful in clinical practice in the near future. Rarer conditions, such as prion disease, might be suggested by rapid onset of cognitive decline accompanied by psychotic symptoms, fasciculations, and myoclonic jerks.

Brain imaging studies are not routinely used for diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, although imaging techniques are rapidly developing and may prove to be clinically useful in the coming years. We recommend their use only when other brain pathologies are suspected, such as infarct, tumor, or subdural hematoma. Medial temporal volumes are reported to be smaller on MRI in patients with mild cognitive impairment than in cognitively normal older adults, and the rate of medial temporal volume loss is reportedly a predictor of conversion to dementia (18) . However, quantification of brain volumes has not been standardized for clinical use.

Medicare covers positron emission tomography for differentiating frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease but not for routine workup of cognitive dysfunction in the absence of dementia. Decreased temporoparietal blood flow on single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) may prove to be a useful predictor for conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s dementia (19) and is sometimes used in the workup of patients with mild cognitive impairment. A SPECT hypoperfusion pattern similar to that seen in Alzheimer’s dementia might suggest a higher risk of conversion to dementia over the next few years.

Transition to Dementia and Predictors

Patients with mild cognitive impairment are at high risk of developing dementia in the near term, and the definition of mild cognitive impairment was developed in part to improve the predictive value of the syndrome. The rate of transition from mild cognitive impairment (narrowly defined, as above) to dementia is estimated to be as high as 10%–15% annually, reaching at least 50% in 5 years (20) . Transition is usually to Alzheimer’s dementia, and less commonly to vascular dementia. In referral clinic populations, most patients with a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment either persist with mild cognitive impairment or progress to dementia, and on autopsy such patients have characteristic neuropathological findings of Alzheimer’s disease, including senile plaques (21) . Given these findings, some investigators believe that mild cognitive impairment is in fact prodromal Alzheimer’s disease and not a separate diagnostic entity (21) . However, in population-based studies, a significant rate of reversion is observed (20%–25%) from mild cognitive impairment to normal cognition and functioning (6) . Patients with mild cognitive impairment who are referred to a general psychiatrist likely fall between these two extremes. Thus, patients with mild cognitive impairment are a high-risk group for developing Alzheimer’s disease, but many will be cognitively and functionally normal at follow-up. Patients should understand that mild cognitive impairment is a syndrome of increased risk and not a definitive diagnosis of a neurodegenerative disease.

Follow-Up and Clinical Management

Because no definitive preventive interventions are available, follow-up and clinical management are necessarily evaluative, educational, and supportive. We recommend office visits every 6–12 months, with office-based cognitive assessments (such as the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination) and careful history taking, including from other informants, conducted at each visit to assess for conversion to dementia. Neuropsychological testing need be repeated only once every 1–2 years or when conversion to dementia is suspected. Educating patients about life style changes (see below) may delay this conversion and may improve patients’ sense of self-efficacy and optimism, which may further prevent the development of depression and anxiety. Useful educational materials on memory disorders are available from the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org) and the National Institute on Aging (www.nia.nih.gov/Alzheimers), and materials on legal and financial planning are available from the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys (www.naela.com).

The clinician should be alert to the development of functional deficits and thus a diagnosis of dementia and should educate patients and families on appropriate life style changes and the potential need for medical, legal, and financial planning should dementia occur.

Treatment Options in Mild Cognitive Impairment

Medications

A pharmacological treatment of mild cognitive impairment would be considered successful if it prevented progression of cognitive and functional deficits and the development of dementia. However, to date there is no proven treatment. In randomized clinical trials, cholinesterase inhibitors, rofecoxib (a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug), and vitamin E have failed to prevent progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia. Donepezil was found in a randomized clinical trial to have a transient preventive effect at 1 year, with a larger and more sustained effect in subjects who had at least one apoE4 allele (22) . These results may encourage some clinicians to use donepezil with patients with mild cognitive impairment, but in our opinion the evidence is not strong enough for a recommendation for its routine use.

Life Style Changes

Evidence from population-based longitudinal epidemiologic studies suggests that exercise and physical activity are associated with a lower risk of dementia (23) , and moderate exercise, such as walking three times a week, appears sufficient to demonstrate this association (24) . The strength of the association appears to be related not only to the total number of calories expended on exercise but also to the number of different leisure activities engaged in (24) , which suggests that there is synergy between exercise and cognitive stimulation (see below). These were observational studies, however, and results are awaited from a large multicenter randomized clinical trial of an exercise intervention in older persons that may clarify the effect of exercise on cognition in the elderly (25) . We recommend that patients with mild cognitive impairment exercise at moderate intensity for at least 30 minutes three times a week and that clinicians pay close attention to control of cardiovascular risk factors, including blood pressure, diabetes, and lipid profile.

The role of cognitive stimulation is less firmly established. Number of years of education has been found to be inversely associated with risk of dementia, but because neuropathology in Alzheimer’s disease precedes clinical symptoms by many years (21 , 26) , it is not clear whether education itself is protective or whether persons at lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease are able to proceed farther in their education. Studies have found a reduced risk of dementia in persons who engage in such diverse activities as crossword puzzles, dancing, and volunteer work (23) . There are common themes in these findings, particularly stimulation of verbal and language skills, and some intriguing associations. For example, dancing clearly involves complex psychomotor coordination. A large multicenter randomized clinical trial of cognitive rehabilitation in older persons suggested that specific cognitive areas can be successfully targeted (27) , but no trials to date have provided evidence of cognitive rehabilitation in mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. These observational studies offer only limited evidence, but we nevertheless recommend to patients with mild cognitive impairment that they engage in activities that increase cognitive stimulation, particularly activities that involve language and psychomotor coordination.

Clinicians may find it helpful to maintain a collection of materials and information about local seniors’ organizations and other community resources. In our experience, patients are more likely to follow through with recommendations about life style change if they are given such information at the time of the clinical encounter.

Relationship Between Late-Life Depression and Mild Cognitive Impairment

The differential diagnosis of late-life depression and mild cognitive impairment is particularly challenging because of the overlap of mood and cognitive complaints in older patients. The co-occurrence of depressive and cognitive symptoms doubles in frequency for each 5-year interval past age 70, with 25% of community-dwelling 85-year-olds exhibiting depression and cognitive dysfunction (28) . Depressed patients without dementia exhibit deficits in many cognitive domains that persist after remission of mood symptoms. Late-life depression has been shown to be a prodrome of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment (29 , 30) , and the estimated prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment is 25%. Since neuropathological signs of Alzheimer’s disease precede clinical symptoms by many years, the direction of causality is not clear; depression and Alzheimer’s disease may be different clinical manifestations of Alzheimer’s pathology, depression may be secondary to Alzheimer’s pathology, depression may mediate or enhance Alzheimer’s pathology, or depression may be a separate neurotoxic mechanism entirely. The diagnosis and treatment of mild cognitive impairment and depression in the elderly thus may be intertwined, and future neuroprotective treatments of mild cognitive impairment may need to target depression as well as cognition.

Treatment of major depressive episodes in patients with mild cognitive impairment should follow good clinical practice for any older person, involving both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. The most common and prominent psychological issue is anxiety and fear about what the future may hold and what preparations need to be made. We find that educating patients and families about the uncertain status of mild cognitive impairment and pointing out that it represents a syndrome of increased risk rather than a definitive diagnosis is helpful in alleviating anxiety and allowing for reasonable future planning.

Summary and Recommendations

In the case described in the opening vignette, the clinician told the patient that her symptoms fit the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. He explained that it’s a syndrome of increased risk of developing dementia in the near term (over the next 5 years) but that it includes many persons who will continue to have normal cognition and functioning. He reviewed the MRI findings, pointing out that although loss of brain volume is associated with cognitive decline, it is also associated with normal aging. He noted that the small stroke she had was not likely to be affecting her cognition.

The clinician emphasized life style changes and encouraged her to increase her exercise and to take a half-hour walk two to five times a week. He also encouraged her to continue substitute teaching and to seek out challenging cognitive activities, particularly those involving the use of language. He noted that such life style changes have not been proven to prevent cognitive decline but have some support in observational studies. He recommended that she return every 6 months for reevaluation, and he cautioned her and her husband that if she had any difficulties with driving, such as lapses of judgment or getting lost in familiar areas, they should contact him immediately. The clinician did not prescribe medication but let the patient know that if she noted further functional or cognitive decline, he would likely prescribe a cholinesterase inhibitor.

1. Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG, Steele CD: Practical Dementia Care, 2nd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 2006Google Scholar

2. Kay DWK, Beamish P, Roth M: Old age mental disorders in Newcastle Upon Tyne, I: a study of prevalence. Br J Psychiatry 1964; 110:146–158Google Scholar

3. Graham JE, Rockwood K, Beattie BL: Prevalence and severity of cognitive impairment with and without dementia in an elderly population. Lancet 1997; 349:1793–1796Google Scholar

4. Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, Petersen RC, Ritchie K, Broich K, Belleville S, Brodaty H, Bennett D, Chertkow H, Cummings JL, de Leon M, Feldman H, Ganguli M, Hampel H, Scheltens P, Tierney MC, Whitehouse P, Winblad B; International Psychogeriatric Association Expert Conference on Mild Cognitive Impairment: mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 2006; 367:1262–1270Google Scholar

5. Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, Blank K, Doraiswamy MP, Kalunian DA, Yaffe K; Task Force of American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry: Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14:561–572Google Scholar

6. Panza F, D’Introno A, Colacicco AM, Capurso C, Del Parigi A, Caselli RJ, Pilotto A, Argentieri G, Scapicchio PL, Scafato E, Capurso A, Solfrizzi V: Current epidemiology of mild cognitive impairment and other predementia syndromes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 13:633–644Google Scholar

7. Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, DeKosky ST, Becker JT, Fitzpatrick A, Dulberg C, Breitner J, Lyketsos C, Jones B, Kawas C, Carlson M, Kuller LH: Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study: part 1. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:1385–1389Google Scholar

8. Barnes DE, Alexopoulos GS, Lopez OL, Williamson JD, Yaffe K: Depressive symptoms, vascular disease, and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:273–280Google Scholar

9. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, Backman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC: Mild cognitive impairment: beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med 2004; 256:240–246Google Scholar

10. Petersen RC: Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. Intern Med 2004; 256:183–194Google Scholar

11. Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Bennett DA, Foster NL, Jack CR Jr, Galasko DR, Doody R, Kaye J, Sano M, Mohs R, Gauthier S, Kim HT, Jin S, Schultz AN, Schafer K, Mulnard R, van Dyck CH, Mintzer J, Zamrini EY, Cahn-Weiner D, Thal LJ; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study: Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Arch Neurol 2004; 61:59–66Google Scholar

12. Tschanz JT, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Lyketsos CG, Corcoran C, Green RC, Hayden K, Norton MC, Zandi PP, Toone L, West NA, Breitner JC; Cache County Investigators: Conversion to dementia from mild cognitive disorder: the Cache County Study. Neurology 2006; 67:229–234Google Scholar

13. Rosenberg PB, Onyike CU, Katz IR, Porsteinsson AP, Mintzer JE, Schneider LS, Rabins PV, Meinert CL, Martin BK, Lyketsos CG; Depression of Alzheimer’s Disease Study: Clinical application of operationalized criteria for “Depression of Alzheimer’s Disease.” Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 20:119–127Google Scholar

14. Loewenstein DA, Barker WW, Harwood DG, Luis C, Acevedo A, Rodriguez I, Duara R: Utility of a modified Mini-Mental State Examination with extended delayed recall in screening for mild cognitive impairment and dementia among community dwelling elders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 15:434–440Google Scholar

15. Teng EL, Chui HC: The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48:314–318Google Scholar

16. Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B: The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology 2000; 55:1621–1626Google Scholar

17. Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, Londos E, Blennow K, Minthon L: Association between CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5:228–234Google Scholar

18. Albert MS: Detection of very early Alzheimer disease through neuroimaging. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2003; 17(suppl 2):S63–S65Google Scholar

19. Hirao K, Ohnishi T, Hirata Y, Yamashita F, Mori T, Moriguchi Y, Matsuda H, Nemoto K, Imabayashi E, Yamada M, Iwamoto T, Arima K, Asada T: The prediction of rapid conversion to Alzheimer’s disease in mild cognitive impairment using regional cerebral blood flow SPECT. Neuroimage 2005; 28:1014–1021Google Scholar

20. Petersen RC: Mild cognitive impairment clinical trials. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003; 2:646–653Google Scholar

21. Morris JC, Price AL: Pathologic correlates of nondemented aging, mild cognitive impairment, and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci 2001; 17:101–118Google Scholar

22. Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, Bennett D, Doody R, Ferris S, Galasko D, Jin S, Kaye J, Levey A, Pfeiffer E, Sano M, van Dyck CH, Thal LJ; Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Group: Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2379–2388Google Scholar

23. Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B: An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol 2004; 3:343–353Google Scholar

24. Podewils LJ, Guallar E, Kuller LH, Fried LP, Lopez OL, Carlson M, Lyketsos CG: Physical activity, APOE genotype, and dementia risk: findings from the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. Am J Epidemiol 2005; 161:639–651Google Scholar

25. Rejeski WJ, Fielding RA, Blair SN, Guralnik JM, Gill TM, Hadley EC, King AC, Kritchevsky SB, Miller ME, Newman AB, Pahor M: The lifestyle interventions and independence for elders (LIFE) pilot study: design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials 2005; 26:141–154Google Scholar

26. Riley KP, Snowdon DA, Desrosiers MF, Markesbery WR: Early life linguistic ability, late life cognitive function, and neuropathology: findings from the Nun Study. Neurobiol Aging 2005; 26:341–347Google Scholar

27. Ball K, Berch DB, Helmers KF, Jobe JB, Leveck MD, Marsiske M, Morris JN, Rebok GW, Smith DM, Tennstedt SL, Unverzagt FW, Willis SL; Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly Study Group: Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288:2271–2281Google Scholar

28. Steffens DC, Otey E, Alexopoulos GS, Butters MA, Cuthbert B, Ganguli M, Geda YE, Hendrie HC, Krishnan RR, Kumar A, Lopez OL, Lyketsos CG, Mast BT, Morris JC, Norton MC, Peavy GM, Petersen RC, Reynolds CF, Salloway S, Welsh-Bohmer KA,Yesavage J: Perspectives on depression, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:130–138Google Scholar

29. Geda YE, Knopman DS, Mrazek DA, Jicha GA, Smith GE, Negash S, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Petersen RC, Pankratz VS, Rocca WA: Depression, apolipoprotein E genotype, and the incidence of mild cognitive impairment: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol 2006; 63:435–440Google Scholar

30. Barnes DE, Alexopoulos GS, Lopez OL, Williamson JD, Yaffe K: Depressive symptoms, vascular disease, and mild cognitive impairment: findings from the cardiovascular health study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:273–279Google Scholar