Impact of Psychometrically Defined Deficits of Executive Functioning in Adults With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Abstract

Objective: The association between deficits in executive functioning and functional outcomes was examined among adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Method: Subjects were adults who did (N=213) and did not (N=145) meet DSM-IV criteria for ADHD. The authors defined having deficits in executive functioning as having at least two measures of executive functioning with scores 1.5 standard deviations below those of matched comparison subjects. Results: Significantly more adults with ADHD had deficits of executive functioning than comparison subjects. Deficits of executive functioning were associated with lower academic achievement, irrespective of ADHD status. Subjects with ADHD with deficits of executive functioning had a significantly lower socioeconomic status and a significant functional morbidity beyond the diagnosis of ADHD alone. Conclusions: Psychometrically defined deficits of executive functioning may help identify a subgroup of adults with ADHD at high risk for occupational and academic underachievement. More efforts are needed to identify cost-effective approaches to screen individuals with ADHD for deficits of executive functioning.

Emerging epidemiological data document that at least 4% of the adult population in this country suffers from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and its presence is associated with severe morbidity and disability (1) . Converging evidence from phenotypic, family aggregation, and neuroimaging studies supports the syndromatic continuity of ADHD across the life cycle (2 , 3) .

One of the suspected sources of the morbidity and disability associated with ADHD has been deficits in a group of neuropsychological functions known as executive functions. Hervey et al. (4) and Seidman et al. (5) reviewed a number of published studies addressing neuropsychological performance in adults with ADHD and found that similar patterns of neuropsychological deficits were observed in adults as have been reported in children (6 – 9) . These reviews showed that adults with ADHD commonly exhibit deficits in a wide range of executive functions, including sustained attention, working memory, verbal fluency, as well as motor and mental processing speed (4 , 10 , 11) .

When considering the critical importance of executive function for normal functioning (12) , it is reasonable to assume that deficits of executive functioning are very likely to be associated with functional impairments. However, the available literature on deficits in executive functioning in individuals with ADHD shows group differences, and group findings do not lend themselves easily for clinical use. Thus, very little is known about the functional implications of deficits of executive functioning in individuals with ADHD.

In an effort to bring deficits of executive functioning to clinical use, Biederman et al. (13) defined deficits of executive functioning in an individual by having at least two impaired measures of executive functioning on a battery of tests measuring aspects of executive functioning. This study documented that the presence of deficits of executive functioning in youth with ADHD was associated with a selectively increased risk for school deficits, including grade retention, as well as a decrease in academic achievement relative to other youth with ADHD without deficits of executive functioning. Whether a similar approach can help identify functional deficits in adults with ADHD remains uncertain.

A better understanding of the impact that deficits in executive functioning have in adults with ADHD and how to best assess them have important clinical and scientific implications. The task demands of adult life, including those required by work, being part of a family and raising children, force individuals to organize their finances, pay bills in a timely fashion, file income taxes, drive safely, and keep appointments. Thus, all the areas required in functional executive functions are taxed, including planning, organizing, and inhibition. Moreover, a working definition of a deficit of executive functioning in individuals with ADHD would be extremely beneficial to clinicians dealing with adults with ADHD for treatment planning. For example, different interventions may be needed in remediation of specific academic areas as well as interventions preceding particular occupational pursuits in individuals with ADHD and associated deficits of executive functioning. Finally, distinguishing adults with and without deficits of executive functioning may assist in the research for pharmacological interventions in this area.

To this end, the main aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of deficits in executive functioning on the functional outcomes in a large sample of adults with and without ADHD. Based on the pediatric literature, we hypothesized 1) that psychometrically defined deficits of executive functioning would be identifiable in a subgroup of ADHD adults using a battery of executive function tests and 2) that the presence of psychometrically defined deficits of executive functioning in adults with ADHD will be associated with added functional deficits.

Method

Subjects

Men and women between the ages of 18 and 55 were eligible for this study. We excluded potential subjects if they had major sensorimotor handicaps (e.g., deafness, blindness), psychosis, autism, inadequate command of the English language, or a full-scale IQ less than 80. No ethnic or racial group was excluded.

Subjects with ADHD were ascertained from referrals to a psychiatric clinic at a major university general hospital and media advertisements. We recruited comparison subjects without ADHD through advertisements and e-mail broadcasts to affiliated employees at the same institution.

A three-stage ascertainment procedure was used to select the participants. The first stage was the subject’s referral (for ADHD subjects) or response to media advertisements (for ADHD and comparison subjects). The second stage confirmed (for ADHD subjects) or ruled out (for comparison subjects) the diagnosis of ADHD by using a telephone questionnaire. The questionnaire asked about the symptoms of ADHD and questions regarding study inclusion and exclusion criteria. The third stage confirmed (for ADHD subjects) or ruled out (for comparison subjects) the diagnosis with face-to-face structured interviews with the individuals. Only subjects who received a positive (ADHD subjects) or a negative (comparison subjects) diagnosis at all three stages were accepted. After receiving a complete description of the study, the subjects provided written informed consent, and the institutional review board granted approval for this study.

Psychiatric Assessments

We interviewed all subjects with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (14) to assess psychopathology supplemented with modules from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Epidemiologic Version adapted for DSM-IV (K-SADS-E) (15) to cover ADHD and other disruptive behavior disorders. The structured interview also included questions regarding academic tutoring, repeating grades, and placement in special academic classes.

The interviewers had undergraduate degrees in psychology, and they were trained to high levels of interrater reliability for the assessment of psychiatric diagnosis. We computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having experienced, board-certified child and adult psychiatrists and licensed clinical psychologists diagnose subjects from audiotaped interviews made by the assessment staff. Based on 500 assessments from interviews of children and adults, the median kappa coefficient was 0.98. Kappa coefficients for the diagnosis included the following: ADHD (0.88), conduct disorder (1.00), oppositional defiant disorder (0.90), antisocial personality disorder (0.80), major depression (1.00), mania (0.95), separation anxiety (1.00), agoraphobia (1.00), panic (0.95), obsessive-compulsive disorder (1.00), generalized anxiety disorder (0.95), specific phobia (0.95), posttraumatic stress disorder (1.00), social phobia (1.00), substance use disorder (1.00), and tics/Tourette’s syndrome (0.89). These measures indicated excellent reliability between ratings made by nonclinician raters and experienced clinicians.

A committee of board-certified child and adult psychiatrists and psychologists resolved all diagnostic uncertainties. The committee members were blind to the subjects’ ascertainment group, ascertainment source, and all nondiagnostic data (e.g., neuropsychological tests). Diagnoses were considered positive if, based on the interview results, DSM-IV criteria were unequivocally met to a clinically meaningful degree. We estimated the reliability of the diagnostic review process by computing kappa coefficients of agreement between clinician reviewers. For these clinical diagnoses, the median reliability between individual clinicians and the review committee-assigned diagnoses was 0.87. Kappa coefficients for individual diagnoses included the following: ADHD (1.00), conduct disorder (1.00), oppositional defiant disorder (0.90), antisocial personality disorder (1.00), major depression (1.00), mania (0.78), separation anxiety (0.89), agoraphobia (0.80), panic (0.77), obsessive-compulsive disorder (0.73), generalized anxiety disorder (0.90), specific phobia (0.85), posttraumatic stress disorder (0.80), social phobia (0.90), substance use disorder (1.00), and tic’s/Tourette’s syndrome (0.68).

We created the following categories of disorders for this analysis: mood disorder (major depression with severe impairment and bipolar disorder), multiple anxiety disorder (two or more anxiety disorders), speech/language disorder (language disorder or stuttering), disruptive behavior disorders (childhood conduct and oppositional defiant disorder or adult antisocial personality disorder), and psychoactive substance use disorder (drug or alcohol abuse or dependence). Rates reported reflect a lifetime prevalence of disorders.

Psychosocial Assessments

Social functioning was assessed with the Social Adjustment Scale (16) . As a measure of overall functioning, we used the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (17) , a summary score assigned by the interviewers on the basis of information gathered in the diagnostic structured interview. Socioeconomic status was assessed with the Hollingshead Four Factor Index of Social Status (18) .

Cognitive/Neuropsychological Assessments

Using the methods of Sattler (19) , we estimated full-scale IQ from the vocabulary and block design subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales—III (WAIS-III) (20) . Our interviewers assessed academic achievement with the arithmetic and reading subtests of the Wide Range Achievement Test—III (WRAT-III) (21) . As recommended by Reynolds (22) , we used a statistically corrected discrepancy between IQ and achievement to define learning disability. Based on our review of the literature and our previous neuropsychological work, we chose to assess certain domains of functioning thought to be important in ADHD and to be indirect indices of frontosubcortical brain systems. These included measures of sustained attention/vigilance, planning and organization, response inhibition, set shifting and categorization, selective attention and visual scanning, verbal and visual learning, and memory. The tests used were the following: 1) the copy organization and delay organization subtests of the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure (23 , 24) , (scored with the Waber-Holmes method [25] ); 2) an auditory continuous performance test developed to assess working memory (26) ; 3) perseverative errors and loss of set of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (27) ; 4) the total words learned on the California Verbal Learning Test (28) ; 5) the color-word raw score of the Stroop test (29) ; and 6) a score based on an additive combination of the WAIS-III digit span and oral arithmetic subtests (20) to approximate the Freedom From Distractibility Index of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Third Edition (WISC-III) (30) used in our previous analysis in a child and adolescent sample.

Defining a Binary Impairment Indicator of Executive Functioning Deficits

Following the method proposed by Biederman et al. (13) , we defined a binary measure of deficits of executive functioning based on the neuropsychological variables just described. For each of the eight executive functioning neuropsychological variables, we defined a threshold with the data from comparison subjects indicating poor performance if the score was 1.5 standard deviations from the mean for normally distributed variables or within the poorest 7th percentile of performance for non-normally distributed variables. We then created binary impairment indicators for the executive function variables for all subjects (ADHD and comparison). Thus, we could sum the number of variables for which any given subject performed poorly based on the cutoffs. We defined a subject as having executive function deficit if two or more tests showed impairment. Three issues contributed to this choice of a cutoff point. First, in our previous report (31) , we found that two or more impaired tests showed the best discrimination between subjects with and without ADHD. Second, while one impaired test may be due to chance, two or more impaired tests would likely be interpreted as a deficit by a clinician. Third, we felt it was inappropriate to place individuals with two abnormal test scores in the nonimpaired group.

Statistical Analysis

To address our hypothesis regarding the effect of deficits of executive functioning, we modeled the outcomes as a function of group status and any confounding variables. Statistical models were fit with the statistical software package STATA (32) . Logistic regression was used for binary outcomes (e.g., lifetime diagnoses), linear regression for continuous outcomes (e.g., GAF scores), and ordinal logistic regression ordinal outcomes (e.g., socioeconomic status). Exact logistic regression was used in lieu of logistic regression when there were one or more zero frequencies in a two-way table defined by the categorical predictor and the dichotomous outcome. Statistical tests were two-tailed, and an alpha level of 0.05 was used to assert statistical significance.

Results

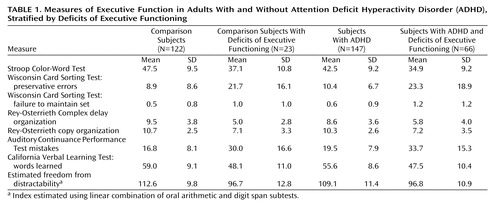

After applying our algorithm for deficits of executive functioning, we defined four groups: comparison subjects without deficits of executive functioning (N=122), comparison subjects with deficits of executive functioning (N=23), subjects with ADHD without deficits of executive functioning (N=147), and subjects with ADHD with deficits of executive functioning (N=66). The degree of executive dysfunction in these groups and the means of the executive function variables for the four groups are presented in Table 1 .

Sixty-six (31%) of the subjects with ADHD were classified as having deficits of executive functioning based on our binary definition used, whereas only 23 (16%) of the comparison participants were (χ 2 =10.56, df=1, p=0.001). As shown in Table 2 , the comparison group was significantly younger than the other three groups, and the ADHD group was significantly younger than the group with ADHD and deficits of executive functioning. Therefore, all subsequent analyses were statistically adjusted for age. No differences were noted in gender across the four groups, and the two ADHD groups did not differ significantly in the rate of current medication use.

There were no differences between ADHD probands with and without deficits of executive functioning in the age at onset of ADHD ( Table 3 ). Although the ADHD deficits of executive functioning group had significantly more lifetime symptoms than the ADHD group (p=0.04), the difference was small ( Table 3 ). No differences between the two groups were found on lifetime inattentive symptoms, lifetime hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, or any category of current symptoms.

The group with ADHD and deficits of executive functioning had significantly lower levels of overall socioeconomic status and occupation compared to the other three groups ( Table 4 ). The group with ADHD and deficits of executive functioning also had lower levels of education compared to the comparison and ADHD groups. In addition, the comparison group had significantly higher levels of overall socioeconomic status, education, and occupation compared to the ADHD group, as well as a higher level of education in relation to the comparison subjects with deficits of executive functioning.

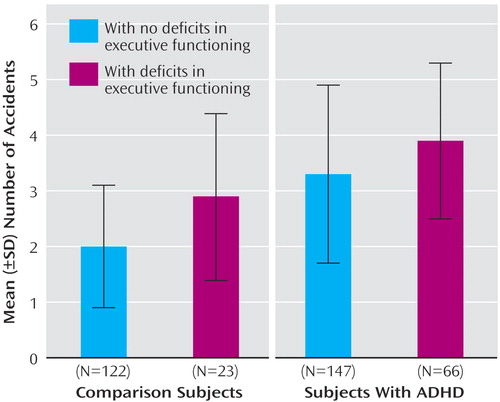

Significant differences between the four groups were found for the number of driving tickets, the number of automobile accidents, and the rate of ever being arrested ( Table 4 and Figure 1 ). Pairwise comparisons showed the same pattern for all three variables. Specifically, both ADHD adults with and without deficits of executive functioning had more tickets, accidents, and a higher arrest rate than the comparison group, and the group with ADHD and deficits of executive functioning had more tickets, accidents, and a higher rate of arrest than the group of comparison subjects and subjects with deficits of executive functioning.

a χ 2 =27.9, df=3, p<0.001.

As shown in Table 4 , there were several significant differences across groups in tests of academic achievement and school functioning. ADHD adults with and without deficits of executive functioning performed significantly worse than the comparison group on arithmetic achievement scores and measures of school functioning, and the group with ADHD and deficits of executive functioning demonstrated significantly poorer performance on every academic outcome and achievement score assessed relative to the ADHD group. School performance did not differ meaningfully in comparison subjects, irrespective of the presence or absence of deficits of executive functioning, but the group of comparison subjects with deficits of executive functioning had significantly poorer achievement scores than the comparison group. In addition, the group with ADHD and deficits of executive functioning scored significantly lower than the comparison group on reading achievement, and the comparison group plus the group with deficits of executive functioning scored significantly lower on reading achievement in relation to the ADHD group.

Significant differences between the groups were also found for the rates of learning disability and IQ scores. The comparison group had a significantly lower rate of learning disability compared to all three other groups. Both groups with deficits of executive functioning had significantly lower full-scale IQ scores compared to both the comparison and the ADHD groups. This pattern of significance was identical for the two subscales of full-scale IQ (block design and vocabulary).

To further test the effect of deficits of executive functioning within ADHD, we ran additional analyses on academic outcomes, including the subjects with ADHD only. We found that the subjects in the group with ADHD and deficits of executive functioning were over two times more likely to have repeated a grade, needed extra help, and been placed in a special class compared with subjects in the ADHD group ( Table 4 ). All three findings remained statistically significant after we controlled for learning disabilities. Among adults with ADHD, deficits of executive functioning were associated with a statistically significant average decrease of over 12 points on the IQ score, a result that remained significant after we controlled for learning disabilities ( Table 4 ). Deficits of executive functioning were also associated with a significant average decrease of seven points on the WRAT-III reading score and over 13 points on the WRAT-III arithmetic score. The WRAT-III findings remained significant after we controlled for learning disabilities, but only the WRAT-III arithmetic finding remained significant after control for IQ.

Table 5 shows the social and psychiatric outcomes in adults with ADHD and comparison subjects, stratified by deficits of executive functioning. Although ADHD subjects were significantly more impaired on global functioning (GAF scores) than comparison subjects, the difference was not associated with deficits of executive functioning. Social Adjustment Scale scores showed that within the comparison group, deficits of executive functioning were a significant factor between the two groups on the overall Social Adjustment Scale score measuring psychosocial functioning. Among the subjects with ADHD, deficits of executive functioning did not have that effect on the overall score. However, for the social and leisure score ( Table 6 ), the group with ADHD and deficits of executive functioning scored poorer than the ADHD group.

Discussion

We examined the functional impact of psychometrically defined deficits of executive functioning in a large sample of adults with and without ADHD. Deficits of executive functioning were significantly more common in subjects with ADHD relative to comparison subjects. Among the subjects with ADHD, deficits of executive functioning had significant negative effects on school functioning, social class, educational and occupational attainments, as well as adaptive social and leisure functioning. These findings extend previously documented results in pediatric samples indicating that the presence of deficits of executive functioning in ADHD subjects is associated with significant functional morbidity beyond that conferred by the diagnosis of ADHD alone (13) .

The rate of comorbid deficits of executive functioning (31%) in this group of adults with ADHD is consistent with a recently published study documenting similar percentages of deficits of executive functioning (33%) in pediatric subjects with ADHD using similar methods (13) . Taken together, these results indicate that deficits of executive functioning should be seen as a discrete cognitive comorbidity within ADHD that can have significant effects upon selective aspects of an individual’s adaptive behavior and not as a diagnostic indicator for ADHD itself.

Also consistent with the pediatric study (13) is the finding that deficits of executive functioning were associated with a significant and detrimental impact on academic functioning in adults with ADHD, beyond those resulting from ADHD itself. Although adults with ADHD with associated deficits of executive functioning exhibited the poorest educational outcomes, comparison subjects with deficits of executive functioning also had significant deficits in academic outcomes relative to comparison subjects without deficits of executive functioning. Altogether, these results suggest that deficits of executive functioning alone cause impairment in educational outcomes, and this is compounded by the impairment caused by ADHD.

Results in this study indicating that comparison with deficits of executive functioning had significantly lower IQs than their nonaffected counterparts are consistent with the literature that has documented that deficits of executive functioning have an effect on IQs (33 , 34) . Considering that ADHD alone takes a toll on the development of intelligence (35 – 37) , the combination of ADHD with deficits of executive functioning has a considerable negative impact on the IQs of adults.

Our results show that adults with ADHD and comorbid deficits of executive functioning had significantly worse occupational outcomes than adults with ADHD without deficits of executive functioning. These results suggest that deficits of executive functioning compound the already compromised workplace functioning of an adult with ADHD. Although work difficulties have been well documented in adults with ADHD (3 , 38 , 39) , our present findings indicate that comorbid deficits of executive functioning may account for some of these deficits. Additionally, adults with ADHD and deficits of executive functioning had a significantly lower socioeconomic status than the other three groups, which suggests that the combination of impairment caused by both ADHD and deficits of executive functioning is particularly pernicious.

In contrast, the presence of deficits of executive functioning had limited impact on other correlates of ADHD, including age at onset of ADHD, number of symptoms, ADHD-associated driving impairments, histories of arrests and patterns of psychiatric comorbidity. These results suggest that deficits of executive functioning selectively moderate specific aspects of ADHD: associated morbidity, including educational and occupational attainments as well as use of leisure time. If confirmed in future studies, our proposed definition of deficits of executive functioning could help identify individuals with ADHD and associated deficits of executive functioning in clinical and research groups.

Our results should be considered in light of several methods limitations. Although our cutoff for deficits of executive functioning, defined as two or more tests 1.5 standard deviations from the mean of the comparison subjects has face validity as a clinically relevant standard of deficits of executive functioning and has been validated in prior work with children (13) , we recognize that it may result in the loss of some information. Although the strong correlation between the factor-analyzed test battery in our parallel article in children and the number of tests impaired somewhat assuaged this concern, we considered this loss of information to be a reasonable trade-off for the applicability and clinical relevance of our method. Neuropsychologists often struggle with a clear diagnosis of deficits of executive functioning based on numerous tests that each assess a different domain of executive functioning. Having a method for clearly defining a diagnosis in a manner similar to counts on many of DSM diagnoses would assist in the appropriate treatment recommendations for individuals. Since the majority of our subjects were Caucasians, our results may not generalize to other ethnic groups. Another methodological shortcoming is the limited power we had to detect differences between comparison subjects with and without deficits of executive functioning.

Despite these considerations, our results show that the presence of psychometrically defined deficits of executive functioning can help identify a sizable minority of individuals with ADHD at high risk for deficits in educational and occupational functioning and the use of leisure time. More work is needed to help address deficits of executive functioning in individuals with ADHD.

1. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Connors CK, Demler O, Faraone SV, Greenhill LL, Howes MJ, Secnik K, Spencer T, Ustun TB, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM: The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:716–723Google Scholar

2. Faraone SV: Genetics of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2004; 27:303–321Google Scholar

3. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer T, Wilens T, Seidman LJ, Mick E, Doyle A: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: an overview. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:9–20Google Scholar

4. Hervey AS, Epstein J, Curry JF: Neuropsychology of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology 2004; 18:485–503Google Scholar

5. Seidman LJ, Doyle A, Fried R, Valera E, Crum K, Matthews L: Neuropsychological function in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2004; 27:261–282Google Scholar

6. Pennington BF, Ozonoff S: Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1996; 37:51–87Google Scholar

7. Seidman LJ, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Weber W, Ouellette C: Toward defining a neuropsychology of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder: performance of children and adolescents from a large clinically referred sample. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65:150–160Google Scholar

8. Seidman L, Biederman J, Monuteaux M, Weber W, Faraone SV: Neuropsychological functioning in nonreferred siblings of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2000; 109:252–265Google Scholar

9. Barkley R: Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol Bull 1997; 121:65–94Google Scholar

10. Gallagher R, Blader J: The diagnosis and neuropsychological assessment of adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: scientific study and practical guidelines. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001; 931:148–171Google Scholar

11. Lovejoy DW, Ball JD, Keats M, Stutts ML, Spain E, Janda L, Janusz J: Neuropsychological performance of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): diagnostic classification estimates for measures of frontal lobe/executive functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1999; 5:222–233Google Scholar

12. Barkley RA: The executive functions and self-regulation: an evolutionary neuropsychological perspective. Neuropsychol Rev 2001; 11:1–29Google Scholar

13. Biederman J, Monuteaux M, Seidman L, Doyle AE, Mick E, Wilens T, Ferrero F, Morgan C, Faraone SV: Impact of executive function feficits and ADHD on academic press outcomes in children. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004; 72:757–766Google Scholar

14. First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

15. Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children: Epidemiologic Version. Fort Lauderdale, Fla, Nova University, 1987Google Scholar

16. Weissman MM, Bothwell S: Assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:1111–1115Google Scholar

17. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: 4th ed text revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

18. Hollingshead AB: Four Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, Conn, Yale Press, 1975Google Scholar

19. Sattler J: Psychological Assessment. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1988Google Scholar

20. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corporation, 1997Google Scholar

21. Jastak JF, Jastak S: Wide Range Achievement Test–Third Edition. Wilmington, Del, Jastak Associates, 1993Google Scholar

22. Reynolds CR: Critical measurement issues in learning disabilities. J Spec Educ 1984; 18:451–476Google Scholar

23. Osterrieth PA: Le test de copie d’une figure complexe. Arch de Psychol 1944; 30:206–256Google Scholar

24. Rey A: L’examen psychologique dans les cas d’encephalopathie traumatique. Les Archives de Psychologie 1941; 28:286–340Google Scholar

25. Bernstein JH, Waber DP: Development scoring system for the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1996Google Scholar

26. Seidman LJ, Breiter HC, Goodman JM, Goldstein JM, Woodruff PW, O’Craven K, Savoy R, Tsuang MT, Rosen BR: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of auditory vigilance with low and high information processing demands. Neuropsychiatry 1998; 12:505–518Google Scholar

27. Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual: Revised and Expanded. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1993Google Scholar

28. Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA: California Verbal Learning Test–Adult Version. New York, the Psychological Corporation, 1987Google Scholar

29. Golden CJ: Stroop Color and Word Test: A Manual for Clinical and Experimental Use. Chicago, Stoelting, Co, 1978Google Scholar

30. Wechsler D: Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Third Edition. San Antonio, Tex, the Psychological Corporation, 1991Google Scholar

31. Doyle AE, Biederman J, Seidman L, Weber W, Faraone S: Diagnostic efficiency of neuropsychological test scores for discriminating boys with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:477–488Google Scholar

32. Stata Corporation: STATA Reference Manual: Release 5. College Station, Tex, Stata Corporation, 1997Google Scholar

33. Sonuga-Barke EJ, Lamparelli M, Stevenson J, Thompson M, Henry A: Behaviour problems and pre-school intellectual attainment: the associations of hyperactivity and conduct problems. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1994; 35:949–960Google Scholar

34. Woods SP, Lovejoy DW, Stutts ML, Ball JD, Fals-Stewart W: Diagnostic utility of discrepancies between intellectual and frontal/executive functioning among adults with ADHD: considerations for patients with above-average IQ. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2000; 15:775Google Scholar

35. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Krifcher Lehman B, Spencer T, Norman D, Seidman L, Kraus I, Perrin J, Chen W, Tsuang MT: Intellectual performance and school failure in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and in their siblings. J Abnorm Psychol 1993; 102:616–623Google Scholar

36. Barkley RA: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and IQ. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

37. Mahone EM, Hagelthorn KM, Cutting LE, Schuerholz LJ, Pelletier SF, Rawlins C, Singer HS, Denckla MB: Effects of IQ on executive function measures in children with ADHD. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn Sect C Child Neuropsychol 2002; 8:52–65Google Scholar

38. Kessler RC: Prevalence of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), in 2004 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Association, 2004, p 6Google Scholar

39. Nadeau KG (ed): A Comprehensive Guide to Attention Deficit Disorder in Adults: Research, Diagnosis, Treatment. New York, Brunner/Mazel Publishers, 1995Google Scholar