Influence of a Functional Polymorphism Within the Promoter of the Serotonin Transporter Gene on the Effects of Total Sleep Deprivation in Bipolar Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A functional polymorphism in the transcriptional control region upstream of the coding sequence of the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter (5-HTT) has been reported. This polymorphism has been shown to influence the antidepressant response to fluvoxamine and paroxetine. The authors tested the hypothesis that the allelic variation of the 5-HTT-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) could influence the response of depressed patients to total sleep deprivation. METHOD: Sixty-eight drug-free inpatients with bipolar depression underwent a night of total sleep deprivation. 5-HTTLPR was genotyped in these patients. Changes in perceived mood were rated on a visual analogue scale and analyzed by using repeated measures analysis of covariance. RESULTS: Patients who were homozygotic for the long variant of 5-HTTLPR showed a significantly better mood amelioration after total sleep deprivation than those who were heterozygotic and homozygotic for the short variant. CONCLUSIONS: The influence of 5-HTTLPR on response to total sleep deprivation is similar to its observed influence on response to serotonergic drug treatments. This finding supports the hypothesis of a major role for serotonin in the mechanism of action of total sleep deprivation in depression.

The mechanism of action of total sleep deprivation in depression is still unclear. Total sleep deprivation enhances the functioning of several neurotransmitter systems, including brain serotonin (5-HT) pathways (1). The observation of a synergistic clinical effect between total sleep deprivation and the β adrenoreceptor/5-HT1A antagonist pindolol, similar to that observed with pindolol and serotonergic drugs, supports a role for brain 5-HT in the mechanism of action of total sleep deprivation (2).

A functional polymorphism in the transcriptional control region upstream of the coding sequence of the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) has been reported, and in vitro studies showed that the basal transcriptional activity of the long variant of this 5-HTT-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) was more than twice that of the short form (3). In agreement with these findings, a study in postmortem human brain tissue showed that subjects who were homozygotic for the long variant had higher 5-HTT mRNA levels than those who were heterozygotic and those who were homozygotic for the short variant (4). Moreover, in families with obsessive-compulsive disorder, subjects who were homozygotic for the long variant and heterozygotic had higher blood 5-HT levels than subjects who were homozygotic for the short variant (5).

From a clinical perspective, 5-HTTLPR has been shown to influence the individual response to serotonergic drugs: depressed inpatients who were homozygotic for the long variant and heterozygotic had a better response to both fluvoxamine (6) and paroxetine (7) than those who were homozygotic for the short variant.

If 5-HTTLPR has a clinically relevant influence on 5-HT function, and if total sleep deprivation acts by enhancing 5-HT transmission, it can be hypothesized that 5-HTTLPR may be associated with different effects of total sleep deprivation in depression. We tested this hypothesis in a homogeneous group of patients with bipolar disorder.

METHOD

Sixty-eight inpatients who had been drug free for at least 7 days were studied. All had a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder type I, depressive episode without psychotic features. Inclusion criteria were the same as described elsewhere (2). The study was approved by the local ethical committee of our hospital. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. The 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (8) was administered at the beginning of the study.

All patients underwent a night of total sleep deprivation (day 1) followed by a night of undisturbed sleep (day 2) (36 hours awake). The patients rated their mood levels on days 1–3 on a visual analogue scale (2) three times during the day. Scores of 0, 50, and 100 on this scale denoted depression, euthymia, and euphoria, respectively. The patients’ perceived mood level on each day was calculated as the mean of the three scores for that day. Baseline clinical characteristics were analyzed by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

To evaluate the association between 5-HTTLPR and the effects of total sleep deprivation, self-ratings of mood before and after total sleep deprivation (days 1 and 2) were analyzed with a two-way repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with time and genotype as independent factors and age at onset as covariate. Genotyping of 5-HTTLPR was performed as described elsewhere (9), by personnel blind to the clinical course of illness and to the effects of total sleep deprivation.

RESULTS

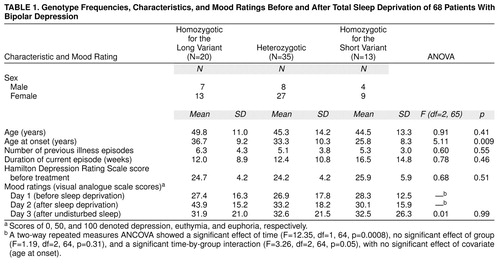

Genotype frequencies, patient characteristics, visual analogue scale scores, and ANOVA results are shown in table 1. Genotype frequencies were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and similar to those in the general population (9). Age at onset was significantly different among genotype groups.

A two-way repeated measures ANCOVA on day 1 and 2 visual analogue scale scores showed a significant effect of time, no significant effect of group, and a significant time-by-group interaction (Table 1), with no significant effect of covariate (age at onset). No regression relationship was found between age at onset and visual analogue scale scores at any time.

On day 3, patients showed a relapse in depressive symptoms, and mean visual analogue scale scores were again similar among groups.

DISCUSSION

Allelic variation of 5-HTTLPR was associated with a differential effect of total sleep deprivation on perceived mood of patients with bipolar depression: patients who were homozygotic for the long variant showed a better mood amelioration after total sleep deprivation than patients who were heterozygotic and those who were homozygotic for the short variant. The effect was similar to that observed in patients treated with fluvoxamine (6) and paroxetine (7).

This finding supports the hypothesis that 5-HT function plays a role in the mechanism of action of total sleep deprivation in depression. Hanna et al. (5) observed substantial seasonal differences in blood 5-HT levels of patients who were homozygotic for the long variant, but not in those of patients who were heterozygotic or homozygotic for the short variant; these authors suggested that presence of the short allele leads to a “higher stability” of 5-HT function. If mood amelioration after total sleep deprivation is caused by rapid changes in 5-HT function, this hypothesis could explain why response to total sleep deprivation is better in patients who were homozygotic for the long variant, who lack the short allele. Further research examining 5-HT function and 5-HTT functional activity will clarify this point.

Caution is needed in interpreting our results. Replication in independent samples is needed before any firm conclusion can be made on these issues. In particular, the difference in age at onset was not found in previously tested inpatients with unipolar depression (6, 7). Moreover, the association between 5-HTTLPR and response to total sleep deprivation in our study group accounts for 9.3% of the variance in total sleep deprivation effect. This value is consistent with current theories on the effect of a single genomic polymorphism (10), but it suggests the possible involvement of other mechanisms involving 5-HT function as well as other neurotransmitter systems (11).

Received Dec. 21, 1998; revision received March 29, 1999; accepted April 28, 1999. From the Istituto Scientifico Ospedale San Raffaele, Department of Neuropsychiatric Sciences, University of Milan, School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Francesco Benedetti, M.D., Istituto Scientifico Ospedale San Raffaele, Department of Neuropsychiatric Sciences, Via Prinetti 29, 20127 Milano, Italy; [email protected] (e-mail).

|

1. Gardner JP, Fornal CA, Jacobs BL: Effects of sleep deprivation on serotonergic neuronal activity in the dorsal raphe nucleus of the freely moving cat. Neuropsychopharmacology 1997; 17:72–81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Smeraldi E, Benedetti F, Barbini B, Campori C, Colombo C: Sustained antidepressant effect of sleep deprivation combined with pindolol in bipolar depression: a placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999; 20:380–385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol S, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Müller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL: Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 1996; 274:1527–1531Google Scholar

4. Little KY, McLaughlin DP, Zhang L, Livermore CS, Dalack GW, McFinton PR, DelProposto ZS, Hill E, Cassin BJ, Watson SJ, Cook EH: Cocaine, ethanol, and genotype effects on human midbrain serotonin transporter binding sites and mRNA levels. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:207–213Link, Google Scholar

5. Hanna GL, Himle JA, Curtis GC, Koram DQ, Weele JV, Leventhal BL, Cook EH Jr: Serotonin transporter and seasonal variation in blood serotonin in families with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998; 18:102–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Smeraldi E, Zanardi R, Benedetti F, Di Bella D, Perez J, Catalano M: Polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene and antidepressant efficacy of fluvoxamine. Mol Psychiatry 1998; 3:508–511Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Zanardi R, Benedetti F, Di Bella D, Catalano M, Smeraldi E: Efficacy of paroxetine in depression is influenced by a functional polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene. J Clin Psychopharmacol (in press)Google Scholar

8. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Deckert J, Catalano M, Heils A, Di Bella D, Friess F, Politi E, Franke P, Nöthen MM, Maier W, Bellodi L, Lesch KP: Functional promoter polymorphism of the human serotonin transporter: lack of association with panic disorder. Psychiatr Genet 1997; 7:45–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Comings D: Polygenic inheritance in psychiatric disorders, in Handbook of Psychiatric Genetics. Edited by Blum K, Noble EP. Boca Raton, Fla, CRC Press, 1997, pp 235–260 Google Scholar

11. Ebert D, Berger M: Neurobiological similarities in antidepressant sleep deprivation and psychostimulant use: a psychostimulant theory of antidepressant sleep deprivation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998; 140:1–10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar