Memory Self-Appraisal in Middle-Aged and Older Adults With the Apolipoprotein E-4 Allele

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Because subjective memory complaints may indicate subtle functional brain abnormalities, the authors studied the influence of the major genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease, the apolipoprotein E-4 (APOE-4) allele, on self-reports of memory performance in middle-aged and older adults. METHOD: Subjective and objective assessments of memory performance were compared in relation to the presence or absence of the APOE-4 allele in 39 cognitively intact persons with mild memory complaints. RESULTS: Subjects with the APOE-4 allele had lower scores on objective verbal memory and on the subjective memory measure for retrospective functioning. Among the subjects in the age range where APOE-4 has its greatest influence on the risk of Alzheimer’s disease (55–74 years), the APOE-4 group had lower scores on the subjective memory measure for frequency of forgetting. Moreover, the standardized difference in retrospective functioning scores between the two genetic risk groups increased when the mid-age-range group was examined rather than the whole study group. CONCLUSIONS: The APOE-4 allele is associated with increased subjective memory impairment in middle-aged and older adults. Longitudinal studies of age-related memory loss should include genetic risk and subjective memory measures as potential predictors of decline.

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common cause of age-related mental decline, accounts for approximately two-thirds of cases of late-life dementia (1). For the common form of Alzheimer’s disease that begins after age 60 years, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) locus on chromosome 19 is associated with both familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (2, 3). The APOE gene has three allelic variants, numbered 2, 3, and 4. The APOE-4 allele has a dose-related effect on increasing risk and lowering age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease (2, 3). When combined with clinical criteria, APOE genotyping improves specificity of the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (4).

Since the discovery that the APOE-4 allele is a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, investigators have extended APOE studies to milder forms of age-related cognitive loss, emphasizing relationships between APOE genetic risk and objective neuropsychological performance. For example, several groups (5, 6) have shown that the APOE-4 allele predicts future cognitive decline in older persons with mild cognitive impairment, defined by significant impairment in delayed recall. The magnitude of such genetic effects will vary depending on the population studied (6).

Regardless of the degree of objective memory loss, many people express concern about subjective, age-related memory changes. Self-appraisal of memory (i.e., meta-memory or subjective memory) has a varying relationship to objective performance (7, 8). In previous studies of people with age-associated memory impairment, we found that a memory self-appraisal measure, mnemonic usage, predicted future objective cognitive decline after 3 years of follow-up (8) and was correlated with frontal lobe glucose metabolism, as measured by positron emission tomography (9). Schofield and co-workers (10) also recently found that memory complaints predict subsequent cognitive decline in older nondemented persons. Thus, a person’s self-awareness of memory performance may indicate subtle functional brain changes and predict future cognitive losses. To our knowledge, the present study is the first ever to explore the relation between the major known genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease, the APOE-4 allele, and subjective memory measures in middle-aged and older persons.

METHOD

The 39 subjects (35 Caucasian, three Asian, and one Hispanic) were part of a larger longitudinal study of mild age-related memory loss designed to determine neuropsychological, neuroimaging, and genetic predictors of subsequent cognitive decline. The subjects ranged in age from 50 to 82 years (mean=65.7 years, SD=9.3) and were recruited through newspaper advertisements, media coverage, and other referrals. All were aware of mild memory changes of gradual onset.

Standardized laboratory screening tests for a dementia evaluation (1) and magnetic resonance imaging scans were performed to uncover potentially treatable causes of mental impairment. In order to eliminate people with conditions that could reduce memory performance, volunteers with neurological and medical disorders or such psychiatric conditions as depression, as well as those taking psychoactive medications, were excluded from participation. Family histories of subjects’ relatives were obtained and corroborated by medical records. A positive family history was defined as one or more first-degree relatives (parent, sibling) with documented Alzheimer’s disease. Volunteers with ambiguous family histories were excluded. A negative family history was defined as no first-degree or second-degree relative with a history of dementia. Of the 306 volunteers, 267 were excluded because of illnesses or medications that could influence memory (N=141), age younger than 50 years (N=75), unclear or ambiguous family history (N=26), or other reasons (e.g., geographic distance, loss of interest) (N=25).

A neuropsychological test battery was administered to quantify cognitive performance (11). For the present study, two measures sensitive to mild cognitive losses assessed objective memory performance: one measure of verbal memory (the Buschke-Fuld Selective Reminding Test [12], total recalled) and one measure of visual spatial memory (the Benton Visual Retention Test [13], total errors). These tests are sensitive indicators of short-term and secondary memory impairment. Both have been widely used in research on normal aging, and both appear to have value in predicting subsequent dementia in clinically normal samples (14–16).

Self-appraisal of everyday memory functioning was assessed with the Memory Functioning Questionnaire (17), a frequently used instrument with high internal consistency and moderate concurrent validity with memory performance measures (18). The Memory Functioning Questionnaire consists of 64 items rated on 7-point scales and provides four unit-weight factor scores measuring frequency of forgetting, seriousness of forgetting, retrospective functioning (changes in current memory ability relative to earlier life), and use of mnemonics. Higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived memory functioning. Both the frequency-of-forgetting factor, which assesses 28 specific situations and five general memory performance areas, and the retrospective functioning factor, which assesses changes in current memory ability relative to five points earlier in life, indicate general deficiencies in memory self-appraisal.

DNA was obtained from blood samples, and APOE genotypes were determined with the use of standard techniques, as previously described (2, 3). All clinical procedures were performed by investigators blind to the genetic findings. Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the procedures set by the UCLA Human Subjects Protection Committee.

Demographic and clinical characteristics and objective and subjective memory measures of the two genetic risk groups (those with and without APOE-4) were compared with the use of t tests; rates of family history and gender were compared with the use of chi-square tests. Because previous studies have found that APOE effects on the risk of Alzheimer’s disease may be greatest for midrange onset ages (e.g., 60–75 years) (19, 20), we conducted a second comparison including only subjects aged 55–74 years. To examine the possible effect of family history, t tests for differences between the genetic risk groups were performed with subjects stratified by family history. Differences were considered statistically significant at the p<0.05 level.

RESULTS

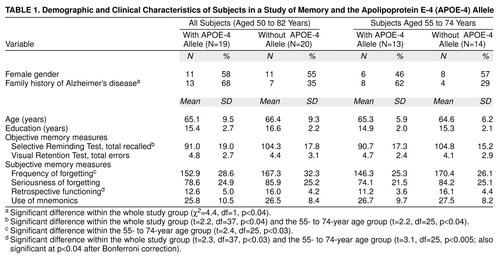

The results are presented in Table 1. Comparisons of the 19 subjects who had the APOE-4 allele with the 20 without the APOE-4 allele indicated no significant differences in age and gender. As expected, the APOE-4 group had a higher rate of family history of Alzheimer’s disease. Mean scores on objective measures of cognitive performance were in the normal range, and the APOE-4 group had lower performance on verbal memory than the non-APOE-4 group. In the subjective memory measure comparisons, the Memory Functioning Questionnaire retrospective functioning factor score was significantly lower in the APOE-4 group than in the non-APOE-4 group.

When we compared only the subjects in the mid-age range (55–74 years), wherein the APOE-4 allele has its greatest effects on risk of Alzheimer’s disease, the group differences in the objective verbal memory measure remained. For the subjective memory measure comparisons, the difference in mean retrospective functioning scores was still significant. Moreover, the standardized difference in retrospective functioning scores between the two genetic risk groups increased from 0.74 to 1.05 when we examined the mid-age-range group rather than the whole group. Another subjective memory measure, frequency of forgetting, also was significantly lower in the midrange APOE-4 group than in the midrange non-APOE-4 group.

We also stratified subjects according to family history. In the subgroup without a family history of Alzheimer’s disease (N=19), subjects with the APOE-4 allele had significantly lower retrospective functioning factor scores on the Memory Functioning Questionnaire than the non-APOE-4 group (t=2.3, df=17, p<0.04). For subjects with a positive family history (N=20), the Memory Functioning Questionnaire retrospective functioning factor score also was lower in the APOE-4 group relative to the non-APOE-4 group, but the difference was not statistically significant (t=0.9, df=18, p=0.37).

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that the APOE-4 allele is associated with greater self-reports of age-related memory complaints in middle-aged and older adults. We also found group differences in the objective verbal memory measure of the Buschke-Fuld Selective Reminding Test, consistent with findings in previous studies of APOE influences on objective memory measures (5, 6).

This association between subjective memory and the APOE-4 allele was even more striking when we limited comparisons to the age group that has the greatest APOE-4 effects on risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Despite the smaller number of subjects for this comparison (N=27, versus N=39), the difference in mean retrospective functioning scores was highly significant, and the groups also differed in mean scores on the frequency-of-forgetting subjective measure. Even if we apply the very conservative Bonferroni correction for multiple statistical testing (12 tests), the difference in mean retrospective functioning scores remains nearly significant for the mid-age-range group comparison (p<0.06).

Because the subject group with the APOE-4 allele also had a significantly higher rate of family history of Alzheimer’s disease, it is possible that these results reflect some other familial influence on self-appraisal of memory, such as additional genetic effects or increased concern about memory changes because of a positive family history. When we tested only subjects in the age group most influenced by APOE, however, the effect size (standardized difference) for the mean retrospective functioning score increased. Moreover, stratifying the study group according to family history indicated greater subjective memory complaints in the APOE-4 subjects regardless of family history of Alzheimer’s disease.

Other methodological issues deserve comment. Although our results were statistically significant, group differences were relatively small and overlapped. Only 13% (N=39 of 306) of the people who volunteered for our study were included, and subjects had a high level of educational achievement. Such sampling bias is similar to that in other studies of age-related memory loss (8, 9, 16). Moreover, our subjects were primarily Caucasian, and allele frequencies may differ considerably by race. Our findings remained significant even when we included only Caucasian subjects in the analysis. Clearly, additional studies are needed to determine whether these results can be generalized to more representative populations.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has attempted to demonstrate an association between the APOE-4 allele and standardized measures of memory self-appraisal. Our results suggest that such measures will be useful to include in additional longitudinal investigations. Prospective studies of age-related memory loss that assess genetic risk and subjective memory will determine how well these measures predict future cognitive decline and the eventual development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Received Oct. 10, 1998; revision received Jan. 20, 1999; accepted Jan. 26, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, the Neuropsychiatric Institute, the Alzheimer’s Disease Center, and the Center on Aging, University of California at Los Angeles; the VA Medical Center, West Los Angeles; the Department of Medicine and the Joseph and Kathleen Bryan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.; Glaxo Wellcome Research and Development, Research Triangle Park, N.C.; and the Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. Address reprint requests to Dr. Small, Room 88-201, UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute, 760 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1759; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants MH-52453, AG-13308, AG-10123, RR-00856, RG-96051, NS-31153, NS-26630, AG-05128, and AG-11268 from NIH; grant IIRG-94101 from the Alzheimer’s Association; grant 95-23330 from the California Department of Health Services; a VA postdoctoral fellowship; the Montgomery Street Foundation; and the Fran and Ray Stark Foundation Fund for Alzheimer’s Disease Research. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

|

1. Small GW, Rabins PV, Barry PP, Buckholtz NS, DeKosky ST, Ferris SH, Finkel SI, Gwyther LP, Khachaturian ZS, Lebowitz BD, McRae TD, Morris JC, Oakley F, Schneider LS, Streim JE, Sunderland T, Teri LA, Tune LE: Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer disease and related disorders: consensus statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the American Geriatrics Society. JAMA 1997; 278:1363–1371Google Scholar

2. Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel D, St George-Hyslop PH, Pericak-Vance MA, Joo SH, Rosi BL, Gusella JF, Crapper-MacLachlan DR, Alberts MJ, Hulette C, Crain B, Goldgaber D, Roses AD: Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1993; 43:1467–1472Google Scholar

3. Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel D, Gaskell P, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA: Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 1993; 261:921–923Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mayeux R, Saunders AM, Shea S, Mirra S, Evans D, Roses AD, Hyman BT, Crain B, Tang MX, Phelps CH: Utility of the apolipoprotein E genotype in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:506–511; correction, 338:1325Google Scholar

5. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Schaid DJ, Thidobeau SN, Kokmen E, Waring SC, Kurland LT: Apolipoprotein E status as a predictor of the development of Alzheimer’s disease in memory-impaired individuals. JAMA 1995; 273:1274–1278Google Scholar

6. Hyman BT, Gomez-Isla T, Briggs M, Chung H, Nichols S, Kohout F, Wallace R: Apolipoprotein E and cognitive change in an elderly population. Ann Neurol 1996; 40:55–66Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Bassett SS, Folstein MF: Memory complaint, memory performance, and psychiatric diagnosis: a community study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1993; 6:105–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Small GW, La Rue A, Komo S, Kaplan A, Mandelkern MA: Mnemonics usage and cognitive decline in age-associated memory impairment. Int Psychogeriatr 1997; 9:47–56Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Small GW, Komo S, La Rue A, Kaplan A, Mandelkern MA: Memory self-appraisal and cerebral glucose metabolism in age-associated memory impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1995; 3:132–143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Schofield PW, Marder K, Dooneief G, Jacobs DM, Sano M, Stern Y: Association of subjective memory complaints with subsequent cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly individuals with baseline cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:609–615Link, Google Scholar

11. Small GW, Okonek A, Mandelkern MA, La Rue A, Chang L, Khonsary A, Ropchan JR, Blahd WH: Age-associated memory loss: initial neuropsychological and cerebral metabolic findings of a longitudinal study. Int Psychogeriatr 1994; 6:23–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Buschke H, Fuld PA: Evaluating storage, retention and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology 1974; 24:1019–1025Google Scholar

13. Benton AL, Hamsher K: Multilingual Aphasia Examination. Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1978Google Scholar

14. Masur DM, Fuld PA, Blau AD, Crystal H, Aronson MK: Predicting development of dementia in the elderly with the Selective Reminding Test. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1990; 12:529–538Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Zonderman AB, Giambra LM, Arenberg D, Resnick SM, Costa PT, Kawa CH: Changes in immediate visual memory predict cognitive impairment. Archives of Clin Neuropsychology 1995; 10:111–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Small GW, La Rue A, Komo S, Kaplan A, Mandelkern MA: Predictors of cognitive change in middle-aged and older adults with memory loss. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1757–1764Google Scholar

17. Gilewski MJ, Zelinski EM, Schaie KW: The Memory Functioning Questionnaire for assessment of memory complaints in adulthood and old age. Psychol Aging 1990; 5:482–490Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Zelinski EM, Gilewski MJ, Anthony-Bergstone CR: Memory Functioning Questionnaire: concurrent validity with memory performance and self-reported memory failures. Psychol Aging 1990; 5:388–399Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Rimmler JB, Locke PA, Conneally PM, Schmader KE, Tanzi RE, Gusella JF, Small GW, Roses AD, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL: Apolipoprotein E, survival in Alzheimer’s disease, and the competing risks of death and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1995; 45:1323–1328Google Scholar

20. Sobel E, Louhija J, Sulkava R, Davanipour Z, Kontula K, Miettinen H, Tikkanen M, Kainulainen K, Tilvis R: Lack of association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease among Finnish centenarians. Neurology 1995; 45:903–907Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar