Treatment of Primary Dysthymia With Group Cognitive Therapy and Pharmacotherapy: Clinical Symptoms and Functional Impairments

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed the efficacy of antidepressant treatment (sertraline) and group cognitive behavior therapy, alone or in combination, in primary dysthymia. The clinical features of dysthymia, as well as the functional impairments associated with the illness (e.g., quality of life, stress perception, coping styles), were evaluated. METHOD: Patients (N=97) diagnosed with primary dysthymia, but no other current comorbid disorder, received either sertraline or placebo in a double-blind design over 12 weeks. In addition, a subgroup of the patients (N=49) received a structured, weekly group cognitive behavior therapy intervention. RESULTS: Treatment with sertraline, with or without group cognitive behavior therapy, reduced the functional impairment of depression. The reductions were similar in the drug-cognitive therapy group and in subjects who received the drug alone. Furthermore, while group cognitive behavior therapy alone reduced the depression scores, this effect was not significantly greater than the effect of the placebo. The drug treatment also induced pronounced improvement in the functional measures, and in some respects these effects were augmented by group cognitive behavior therapy. Among patients who responded favorably to cognitive behavior therapy, the improvements in the functional measures were similar to those who responded to drug treatment, whereas such functional changes were not seen among patients who responded to placebo. CONCLUSIONS: Sertraline treatment effectively reduces the clinical symptoms and functional impairments associated with dysthymia. Although the group cognitive behavior therapy intervention was less effective in alleviating clinical symptoms, it augmented the effects of sertraline with respect to some functional changes, and in a subgroup of patients it attenuated the functional impairments characteristic of dysthymia.

It is well established that both antidepressant agents and cognitive behavior therapy are effective in the treatment of major affective disorder (1–5). In this respect, several meta-analyses have indicated that cognitive therapy is the most effective form of psychotherapy for the treatment of major depression (6, 7) and that it is claimed to be as efficacious as pharmacotherapy. In addition, several investigators reported that the combination of pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy was superior to either treatment alone (8, 9). Others, however, found that the combination of treatments was no better than either treatment applied individually (10, 11). It is of interest that under conditions in which cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy were not more effective than pharmacotherapy alone, the dropout rate was reduced by the combined treatment (12, 13). In addition, relapse was somewhat reduced for patients who received cognitive behavior therapy, a combination of cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy, or cognitive behavior therapy following successful pharmacotherapy (5, 14, 15).

Commensurate with the response to individual cognitive therapy, group cognitive therapy may be a viable therapeutic intervention for major depressive disorder (16–19). However, it was reported that group cognitive behavior therapy was as effective as individual therapy only during the early phases of treatment, after which the latter was more effective (20, 21). Furthermore, while group cognitive behavior therapy effectively attenuated depression, the effectiveness of this treatment was not enhanced by imipramine treatment (17, 22).

In contrast to the large number of studies that have assessed the effects of psychological or behavioral therapies in major depressive disorder, few studies have systematically evaluated the effectiveness of such treatment in dysthymia. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that such forms of therapy may be effective in the treatment of this illness (5, 23, 24). Of course, it remains to be established whether group and individual cognitive behavior therapy are differentially effective in the treatment of this illness. Inasmuch as dysthymia is characterized by low self-esteem and impaired social and interpersonal functioning, cognitive behavior therapy may be particularly useful for the development of more adaptive behavior (23) and for the improvement of negative self-perception. It was further suggested that cognitive behavior therapy may be useful in symptom control and prevention of relapse, particularly when the effects of pharmacotherapy are limited.

The number of studies examining the efficacy of antidepressants in dysthymic patients is limited; however, it is now generally accepted that a significant portion of dysthymic patients respond to pharmacotherapy. This evidence has been derived from clinical trials with tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and, more recently, the newer serotonergic agents (25). The specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been shown to be as effective as the older tricyclics and better tolerated in the treatment of dysthymia (26). It appears that the beneficial effects of the antidepressant agents may be particularly pronounced in certain subgroups of dysthymic patients, notably the subaffective type described by Akiskal (27). In the main, the effects of these agents have been evaluated in open-label trials, although there have been reports showing positive antidepressant effects in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (25, 26). In the present investigation it was hypothesized that 1) an SSRI, sertraline, would be effective in the treatment of dysthymia in a double-blind, placebo-controlled design; 2) group cognitive behavior therapy would be effective in the treatment of dysthymia; and 3) the effects of the drug treatment would be augmented by group cognitive therapy. Inasmuch as symptom improvement may not necessarily parallel functional improvement, particularly with respect to different forms of treatment, the present investigation assessed the impact of the treatments not only on symptom improvement (as measured by standardized instruments such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety), but also on measures of quality of life, alterations of stress perception, and coping styles employed.

METHOD

Subjects

The subjects consisted of 97 patients with primary dysthymia (41 men and 56 women) ranging in age from 21 to 54 years. The patients were respondents to newspaper advertisements that specified the symptoms of dysthymia. Because comorbidity is common in dysthymic disorder, the subjects were carefully screened and were included only if they satisfied the DSM-III-R/DSM-IV criteria for primary dysthymia and were free of any other current axis I disorders and any physical illness. During screening, subjects who manifested significant personality difficulties sufficient for a clinical diagnosis of a personality disorder were excluded from the study. This is not to say that these patients did not exhibit traits associated with personality difficulties but, rather, that these were not of sufficient magnitude to fulfill the DSM-III-R/DSM-IV criteria. Indeed, the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory—II (28) indicated that 38 patients displayed elevated scores on one or more personality patterns (T scores greater than 85). In the main, these subjects showed elevated scores on the avoidant, passive-aggressive, and self-defeating pattern scales in the Millon inventory; however, none of them displayed personality difficulties of sufficient magnitude to necessitate their exclusion from the study. These subjects were represented in the treatment groups to an equivalent degree. None of the study patients fulfilled the criteria for a concurrent major depressive disorder at entry or during the study. In addition, subjects with previously diagnosed major depression or self-reported major depressive disorder or undiagnosed patients with symptoms sufficient to make a retrospective diagnosis of major depressive disorder were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were any physical illness, such as severe allergies; multiple adverse drug reactions; hypertension; significant recurrent dermatitis; or malignant, hematological, endocrine, pulmonary, cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, gastrointestinal, or neurologic disease. Finally, pregnant and lactating women were not included in the investigation.

Nondepressed control subjects were included in the study to obtain normative data regarding quality of life and stress perception at two time points (baseline and week 12). Thus, comparisons could be made with dysthymic patients to determine the extent to which functional impairments were present before treatment and the degree to which the treatments influenced the functional measurements. The normal control subjects (10 men and 15 women), of approximately the same age as the dysthymic subjects, consisted of blue- and white-collar university and hospital staff and were screened with the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Clinician Rated, version 2.1 (29) and a self-rating Beck Depression Inventory (30) in order to exclude any psychopathology. Moreover, control subjects were excluded if they reported a history of any psychiatric illness or psychiatric intervention, if their Beck depression scores exceeded 4, or if they scored higher than 0 on the first item of this scale (pertaining to dysphoria). Other exclusion criteria were any of the physical illnesses listed earlier. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Assessments

At admission, data gathered included demographic information, characteristics of the current episode, and past history and family history of psychiatric illness. Patients underwent a full physical examination and routine clinical investigations. Interrater reliability sessions were routinely conducted to ensure the reliability between clinicians for each of the instruments. Moreover, clinicians performing these ratings were blind to the pharmacotherapy the subjects received, and, unless it was disclosed by the patients, the raters were unaware of the cognitive treatment that had been administered. Symptoms of depression were measured with standardized instruments, including the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (31), the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (32), the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (33), and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) of severity (34). In addition, the Cornell Dysthymia Rating Scale (35) was administered to patients. However, because this scale was published after the present study began, it was administered to only 52 of the patients in the present investigation. Finally, although efficacy and tolerability measures were taken at the screen and baseline visits, as well as at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12, only the baseline and final (week 12) measures are presented in the present report.

After the diagnostic interview, all patients underwent a 1-week placebo washout to establish whether a rapid placebo response would be evident. None of the patients had taken any psychotropic medication for at least 6 months before the study began. The protocol required the elimination from the study of early placebo responders, i.e., any patients with a significant reduction in depressive symptoms (i.e., a drop by 50% or more, and a score of 10 or less, on the Hamilton depression scale) at the end of the 1-week placebo washout. However, none of the patients showed such an early placebo response. On the last day of the washout, subjects were asked to complete a series of questionnaires that rated stressful life experiences and coping styles used. These included the Daily Hassles and Uplifts Scales to determine minor day-to-day life stressors and positive experiences (36), the Battelle Quality of Life Scale (37), and the Coping Strategies Scales (38). The Battelle Quality of Life Scale is divided into several dimensions including health perception, bed disability days, energy/vitality, cognitive functioning, alertness, work behavior, home management, social interaction, and life satisfaction. The Coping Strategies Scale is subdivided into 10 subcomponents and three composite scales. Of these, several showed high correlations with one another, and thus only the composite scales, comprising emotional expression and social support seeking, emotional containment and passivity, and individual coping and cognitive restructuring, were considered in the present analysis.

Pharmacotherapy

Following screening and the placebo washout phase, the patients were randomly assigned to groups on a double-blind basis, determined by a computer-generated schedule in which treatments were balanced within blocks of consecutive patients. A total of 47 patients received sertraline, and 50 received placebo. The initial dose of sertraline was 50 mg/day, with increases by 50-mg increments every 2 weeks, to a maximum dose of 200 mg/day, as determined by treatment response and adverse events. The dose at week 8 was carried through to 12 weeks. The average maximal dose received was 177.90 mg/day (SD=28.72, range=100–200). The pharmacological agent was administered each morning with breakfast. The only concurrent psychotropic medication permitted during the study period was temazepam, up to 30 mg at night, as a hypnotic on an as-needed basis. The use of temazepam was infrequent and did not differ between the groups. The clinicians providing pharmacotherapy and others providing psychotherapy were kept blind to the form of treatment that patients received.

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Of the drug-treated patients, 25 received group cognitive therapy, and 22 did not. Moreover, of the placebo-treated patients, 24 received cognitive therapy, and 26 did not. The cognitively oriented group therapy intervention involved a structured approach modified from that described by Hollon and Shaw (39). Some of the techniques of cognitive behavior situational analysis (40), which were developed specifically for use with dysthymic patients, were incorporated into the 12-week treatment structured program. Cognitive therapy was administered by two therapists to groups of seven to 10 patients. The lead therapist had 15 years of experience with individual and group cognitive behavior therapy for affective disorders in hospital-based settings, and both therapists had regularly attended updated training courses concerning new developments and techniques in cognitive behavior therapy. Once seven to 10 patients had been recruited for the group cognitive behavior therapy, the trial commenced (maximum of 3 weeks). The therapy consisted of 12 weekly 90-minute sessions conducted concurrently with the pharmacotherapy trial. Topics included 1) the relationship between thinking and mood, 2) identification of dysfunctional thoughts, 3) examples of mood lowering and the rating of emotions, 4) pleasure and mastery of activities, 5) automatic thoughts and rational responses, 6) cognitive distortions, 7) core beliefs, 8) assertiveness, and 9) individual issues and situational analyses. Each session included a review of the preceding one and the homework that had been assigned. Several important additions were made to the standard cognitive behavior therapy approach through use of the Daily Record of Dysfunctional Thoughts (i.e., situation, emotion, negative automatic thought, rational response, outcome). Rather than a focus on dysfunctional thinking and negative automatic thoughts, emphasis was placed on functional thinking and positive automatic thoughts. Actual and desired outcomes were compared and discussed. Finally, there was more emphasis on general management of the situation rather than predominantly on managing the negative or dysfunctional thinking.

Statistical Analyses

Because the number of subjects relative to the number of variables was relatively small, three separate multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were conducted to assess the effects of the treatments on the clinical measures (Hamilton depression scale, Montgomery-Åsberg depression scale, Hamilton anxiety scale, and CGI), the stress/coping indices (hassles, uplifts, coping styles), and the quality of life subsets. Significant effects were followed by univariate ANOVAs in which the clinical and the behavioral measures were each analyzed as a two (drug treatment)-by-two (cognitive therapy) factorial design with repeated measures (baseline versus posttreatment). Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons were employed to compare the means of the simple effects of the significant interactions. Moreover, the findings were considered meaningful only when effect sizes (ε2) indicated that the treatment accounted for more than 10% of the variance. The nondepressed subjects were treated as an outside control group, and their behavioral scores were compared to those of the dysthymic patients by Dunnett’s tests (alpha set at 0.01). Additional analyses of the behavioral measures were performed to evaluate whether responders and nonresponders differed from one another after 12 weeks of treatment and whether such effects varied as a function of the treatment condition. For this purpose two (drug treatment)-by-two (cognitive therapy)-by-two (responder versus nonresponder) ANOVAs were performed of the quality of life indices after 12 weeks of treatment. The posttreatment scores of the nondepressed control group were compared to those of the dysthymic patients by Dunnett’s tests.

RESULTS

Measures of Clinical Efficacy

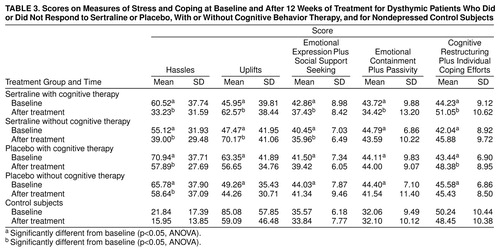

A total of three subjects, two who received placebo and no cognitive therapy and one who received drug treatment and cognitive therapy, did not continue in the study. In none of the cases was this a result of an adverse reaction; rather, the subjects chose to seek an alternative form of treatment elsewhere (e.g., open-label treatment by a community psychiatrist or family physician). Figure 1 shows the 17-item Hamilton depression scale scores for each of the four treatment groups. Because the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and CGI data were congruent with those of the Hamilton depression scale, only data from the Hamilton scale are shown in Figure 1. The Hamilton depression scale scores were on average somewhat higher than those usually obtained, but they were not outside the range of scores reported by other investigators (41). It might be noted at this juncture that the Cornell Dysthymia Rating Scale was highly correlated with the Hamilton and Montgomery-Åsberg depression scales at the baseline visit (r=0.68 and 0.73, respectively, df=50, p<0.001), as well as following treatment (r=0.89 and 0.94, df=50, p<0.001). The MANOVA indicated that the clinical scores varied as a function of the drug treatment-by-assessment period (baseline versus posttreatment)-by-clinical measure interaction (Pillais=0.18; F=5.92, df=3, 83, p<0.01). Univariate ANOVAs confirmed that scores on each of the clinical efficacy measures (Hamilton depression scale, Montgomery-Åsberg depression scale, Hamilton anxiety scale, and CGI) varied as a function of the drug treatment-by-assessment period interaction (F=8.01, 6.46, 18.17, and 6.55, respectively, df=1, 90, p<0.01). The multiple comparisons indicated that at baseline the groups did not differ from one another. The scores on each measure declined over the 12 weeks of treatment. However, the decline was more pronounced for the sertraline- than the placebo-treated subjects. In contrast to the effects of the drug treatment, the MANOVA indicated that neither the cognitive therapy nor any of the interactions involving this variable approached statistical significance. Thus, it would appear, at least at first blush, that cognitive therapy alone was ineffective in significantly alleviating the clinical symptoms of dysthymia and did not significantly augment the effects of pharmacotherapy.

Paralleling the efficacy measures, it appeared that the ratio of responders to nonresponders (responders had a score of 10 or less and at least a 50% decline in Hamilton depression score) was greater in the drug- than in the placebo-treated subjects and that cognitive therapy itself did not lead to a greater number of responders than did no treatment (Table 1). Overall, the percentage of responders in the drug plus cognitive therapy group was greater than in the drug alone group, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. It should be underscored, however, that the power to detect significant differences between the drug and the drug plus cognitive therapy groups was 0.74 and was not sufficient to detect a statistically significant outcome. In fact, for a power of 0.80, approximately 70 subjects would have been necessary for a significant effect. Thus, it is premature to conclude that the combination of drug and cognitive therapy was no different from drug treatment alone.

Quality of Life

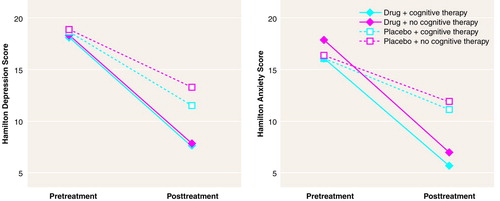

As in the case of the clinical measures, the MANOVA indicated that the quality of life indices did not vary as a function of either the cognitive therapy or any of the interactions involving this variable. In contrast, the quality of life scores varied as a function of the drug treatment-by-assessment period-by-the quality of life subscale interaction (Pillais=0.37; F=3.19, df=9, 67, p<0.01). Subsequent univariate analyses indicated that scores on several of the subscales, including health perception, energy/vitality, cognitive functioning, alertness, social interaction, and life satisfaction, varied as a function of the drug treatment-by-assessment period interaction (F=12.87, 9.60, 13.43, 5.76, 3.80, and 19.64, respectively, df=1, 90, p<0.01). Not unexpectedly, Dunnett’s tests indicated that at baseline, health perception, energy/vitality, cognitive functioning, alertness, social interaction, and life satisfaction among dysthymic patients were impaired relative to nondepressed control subjects. Moreover, among sertraline-treated subjects, each of these indices of quality of life improved over 12 weeks of treatment, such that the scores came to exceed those of placebo-treated patients. However, it is essential to underline that in each instance, the quality of life still differed from that of the control subjects. None of the quality of life components varied as a function of cognitive therapy. Figure 2 depicts the scores on the life satisfaction and social interaction subscales of the quality of life questionnaire, indicating that drug treatment had a positive effect. Identical outcomes were evident with respect to health perception, energy/vitality, cognitive functioning, and alertness (data not shown).

The MANOVA conducted to determine whether the quality of life indices among treatment responders and nonresponders differed from one another revealed that scores varied as a function of the interaction of drug treatment-by-cognitive therapy-by-responder versus nonresponder-by-the quality of life subscale (Pillais=0.30; F=2.32, df=9, 77, p<0.05). Univariate analyses indicated that life satisfaction, social interaction, and energy each varied as a function of the drug treatment-by-cognitive therapy-by-responder versus nonresponder interaction (F=7.32, 8.41, and 3.97, respectively, df=1, 84, p<0.05). As seen in Table 2, among the patients who responded to drug treatment, the quality of life scores were superior to those of nonresponders, and Dunnett’s tests indicated that the scores in these groups approached those of the nondepressed control subjects. Life satisfaction, social interaction, and energy scores among responders to cognitive therapy were also considerably greater than those of placebo responders, as well as those of nonresponders to cognitive therapy. In contrast, among placebo responders, these quality of life scores were not improved relative to those of nonresponders. A similar profile of results was seen with respect to cognitive functioning (Table 2), but this interaction did not reach statistical significance (F=2.44, df=1, 84, p>0.10).

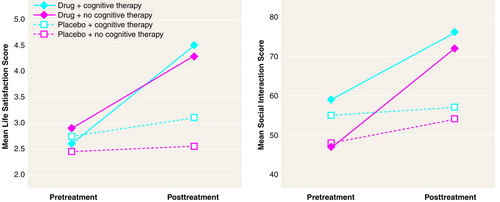

Hassles, Uplifts, and Coping

Because many of the coping measures were found to be highly correlated, the MANOVA included only perceived hassles, uplifts, and the three composite coping measures. This analysis revealed a significant interaction among drug treatment, assessment time, and behavioral variable (Pillais=0.18; F=2.59, df=5, 81, p<0.05). Neither the main effect of cognitive therapy nor the interactions involving this variable reached significance. The perceived hassles and uplifts of patients before and after treatment are shown in Table 3. Table 3 also shows the behavioral scores of untreated control subjects at both of these times. Univariate analyses indicated that hassles and uplifts scores both varied as a function of the drug treatment-by-assessment period (baseline versus week 12 visit) interaction (F=3.80 and 7.20, respectively, df=1, 90, p<0.05 and 0.01). Dunnett’s tests indicated that at baseline the reported hassles of the dysthymic subjects were markedly higher, whereas uplifts were lower, than among control subjects. In each of the dysthymic groups the perceived stress (hassles) declined over the 12 weeks of treatment, but this effect was significantly more pronounced in subjects who received sertraline (p<0.01). As seen in Table 3 and confirmed by Dunnett’s tests, the perceived hassles following drug treatment were still somewhat greater than those for the control subjects. Indeed, even when comparisons were made between treatment responders and control subjects, the hassles reported by the dysthymic patients exceeded those of nondepressed, untreated control subjects.

Among drug-treated subjects perceived uplifts increased over the 12 weeks of treatment, whereas among the placebo subjects no such increase was evident. Among control subjects perceived uplifts declined over the 12-week period, possibly reflecting the boredom associated with completing this lengthy questionnaire. Be this as it may, at week 12 the uplifts of drug-treated patients increased significantly from baseline and were comparable to those of the nondepressed control subjects. A separate analysis was performed to determine whether the uplift scores differed between patients who were responders and those who were not. This analysis confirmed that among drug responders the increase in uplifts was significantly greater than that among nonresponders (F=6.14, df=1, 84, p<0.01) and that performance varied as a function of the drug-by-cognitive treatment interaction (F=3.72, df=1, 84, p<0.05). Among responders to cognitive treatment alone, as in the case of responders to drug treatment, perceived uplifts were approximately twofold greater than among the nonresponders. In contrast, among placebo responders (who had not received cognitive therapy) uplift scores were comparable to those of placebo nonresponders.

The univariate ANOVAs indicated that coping comprising emotional expression plus social support seeking varied as a function of the drug treatment-by-assessment period interaction (F=3.27, df=1, 90, p<0.05). At baseline the depressed groups exhibited greater reliance on this coping style than did nondepressed control subjects. Moreover, following treatment the drug-treated groups displayed reduced emotion expression plus passivity relative to that seen at baseline. It was further observed that coping efforts comprising emotional containment plus passivity varied as a function of the drug treatment-by-cognitive therapy-by-time interaction (F=6.87, df=1, 90, p<0.01). Again, Dunnett’s tests indicated that relative to nondepressed control subjects, emotional containment plus passivity was greater among the dysthymic subjects. Multiple comparisons between the means comprising the drug treatment-by-cognitive therapy-by-assessment time interaction revealed that the dysthymic groups did not differ from one another before treatment. However, following 12 weeks of treatment a marked reduction of emotional containment was apparent in patients who received the combination of drug treatment and cognitive therapy. Such a decline was not evident for patients who received either treatment alone. Finally, it was observed that cognitive restructuring plus individual coping efforts varied as a function of the drug treatment-by-assessment period, as well as the cognitive treatment-by-assessment period interactions (F=4.61 and 7.18, respectively, df=1, 90, p<0.05). The multiple comparisons confirmed that individual coping plus cognitive restructuring was enhanced in patients who received either sertraline treatment or cognitive therapy. Among patients who received both pharmacotherapy and cognitive therapy, additive effects were evident, such that patients who received both therapies exhibited the highest level of improvement (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Several reports have confirmed that like the tricyclics (42–46) and MAOIs (45, 47, 48), the newer antidepressants, including SSRIs such as fluoxetine and sertraline (25, 41, 43, 49–51), the reversible MAOI moclobemide (46, 52–56), and other agents such as the serotonin (5-HT2) antagonist ritanserin (57, 58), is efficacious in the treatment of dysthymia. The present investigation confirmed that relative to placebo, 12 weeks of treatment with sertraline in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial effectively reduced the clinical symptoms of dysthymia as measured by several standard instruments. This finding is in keeping with previous reports concerning the efficacy of sertraline for dysthymic patients (25, 59). In the present study sertraline was also well tolerated, and adverse events were infrequent and only of mild or moderate intensity. Indeed, no dropouts occurred as a result of adverse events. The low rate of attrition was somewhat unusual but may stem from the nature of the subject recruitment and the exclusion of subjects with comorbid conditions, including personality disorders.

In contrast to the effects of the sertraline treatment, results for the group cognitive behavior therapy intervention were not as clear. Cognitive behavior therapy alone was not significantly more effective than placebo in reducing the clinical symptoms of dysthymia. Similarly, group cognitive behavior therapy did not significantly enhance the effectiveness of the pharmacotherapy. Although cognitive behavior therapy produced some enhancement of sertraline treatment, this effect was not significantly superior to the antidepressant alone; however, the number of subjects tested did not provide sufficient power to detect an enhancement of the drug effect. This should not be misconstrued to suggest that cognitive therapy is invariably without effect in dysthymia. As indicated by Hollon and DeRubeis (60), cognitive therapy administered in conjunction with placebo treatment is not representative of the effects of cognitive therapy alone, and the placebo treatment may actually have attenuated some of the effects that might ordinarily be engendered by the cognitive behavior therapy intervention. Furthermore, it is possible that individual cognitive therapy may have yielded a better outcome than did cognitive therapy administered to groups. Moreover, the cognitive behavior therapy intervention in the present investigation was only of 12-week duration, and a more protracted course of treatment may have been required (61), particularly for a long-standing illness such as dysthymia. It is also possible that cognitive behavior therapy adapted specifically for dysthymic patients may have a greater impact than that observed in the present investigation. There is as yet no empirically validated form of cognitive behavior therapy developed specifically for dysthymic patients. It is conceivable, however, that developments in cognitive behavior therapy since the commencement of this study may prove to be more appropriate for this population (62, 63). It remains to be determined whether cognitive therapy, particularly for the drug-treated subjects, would be efficacious in preventing recurrence of dysthymia. In this respect, cognitive therapy may be more advantageous when applied during the maintenance phase of treatment (i.e., on completion of 12 weeks of pharmacotherapy, rather than being applied concurrently during the acute phase of treatment) (64–66).

In addition to modifying the clinical symptoms of dysthymia, pharmacotherapy appeared to effectively reduce residual characteristics associated with the illness. For instance, perceived stress in the form of hassles was reduced, whereas uplifts were increased. Moreover, several of the maladaptive emotion-focused coping strategies, most notably emotional containment, were attenuated with pharmacotherapy. Although cognitive behavior therapy had no effect on clinical symptoms, it improved individual coping and cognitive restructuring, just as pharmacotherapy did, and the two treatments had additive consequences. Emotional containment plus passivity was affected only in patients who received both treatments concurrently. Thus, it would appear that sertraline treatment not only influences the primary clinical characteristics of dysthymia, but also markedly influences the secondary behavioral concomitants of the illness. Moreover, the effects of the drug on coping processes may be augmented by group cognitive therapy.

It has been reported that the quality of life is substantially reduced in depressive disorders (67, 68). Similarly, social and occupational impairments are common in dysthymic patients (42, 69), and antidepressant treatment has been shown to attenuate the social impairments (42). It was similarly observed in the present investigation that dysthymia was accompanied by marked disturbances in various dimensions of the quality of life, including health perception, energy/vitality, cognitive functioning, alertness, social functioning, and life satisfaction. Treatment with sertraline largely attenuated these impairments, just as this treatment reduced perceived stress and enhanced perceived uplifts. Although group cognitive behavior therapy did not have an overall effect on the quality of life, it is interesting that among those patients who responded favorably to this intervention, the enhancement of quality of life scores was as marked as that in drug responders. In contrast, among placebo responders there was no enhancement in quality of life measures. In effect, while placebo responders and those patients who responded favorably to cognitive behavior therapy exhibited similar profiles of symptom alleviation, these two groups could readily be distinguished from one another on the basis of secondary or residual symptoms. Thus, although a positive treatment response was less frequent following group cognitive behavior therapy than after pharmacotherapy, in a subset of patients the cognitive behavior therapy intervention had definite benefits in terms of functional improvement.

It seems that the group intervention used in the present investigation, although subtle in its effects on clinical characteristics, provoked functional changes beyond those seen in placebo responders. It has been proposed that the high rate of recurrence of major depressive disorder may stem from undertreatment of the illness, as reflected by the persistence of residual symptoms (23, 70–73). In a like fashion, it is possible that those treatments which permit residual dysthymic features to persist (e.g., inadequate antidepressant dose or duration of treatment) may also be least effective in preventing recurrence of this illness. It is certainly conceivable that by virtue of its effects on the secondary features of dysthymia, cognitive behavior therapy may act to limit illness recurrence. As indicated earlier, forms of cognitive behavior therapy that incorporate recent advances in this approach and are tailored toward the whole spectrum of specific symptoms of dysthymia may also prove to be more efficacious in this respect (74, 75). Finally, given that changes in the quality of life distinguished between patients who responded to cognitive therapy and to placebo, the possibility ought to be considered that this functional measure may also be useful in distinguishing genuine drug responders from drug-treated patients actually exhibiting a placebo response. Such a differentiation may prove to be a valuable tool in predicting relapse and may be useful in evaluating the efficacy of treatment.

Presented at the 6th World Congress of Biological Psychiatry, Nice, France, June 22–27, 1997; and at a meeting of the Canadian Psychiatric Association, Calgary, Alta., Canada, Sept. 17–19, 1997. Received June 19, 1998; revision received Jan. 20, 1999; accepted March 4, 1999. From the Institute of Mental Health Research at Royal Ottawa Hospital, Ont., Canada; the Department of Psychiatry and School of Psychology and Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of Ottawa; and the Institute of Neuroscience, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ont., Canada. Address reprint requests to Dr. Ravindran, Department of Psychiatry, University of Ottawa, 1145 Carling Ave., Ottawa, Ont. K1Z 7K4, Canada. Supported by a grant from the Medical Research Council of Canada in collaboration with the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of Canada and by Pfizer Canada, Inc. The authors thank Connie Waddell, Karen Gerbasi, and Lena Dipietro for their assistance and Dr. J.C. Markowitz and Dr. M.E. Thase for their comments.

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. Hamilton Depression Scale and Hamilton Anxiety Scale Mean Scores at Baseline and After 12 Weeks of Treatment for 94 Dysthymic Patients Who Received Sertraline and Cognitive Group Therapy, Sertraline Alone, Cognitive Group Therapy and Placebo, or Placebo Alonea

aStandard deviations for the mean scores at baseline and after 12 weeks were as follows: for the drug and cognitive therapy group, SD=4.13 and 5.93 (depression) and SD=4.70 and 5.89 (anxiety); for the drug alone group, SD=3.87 and 5.50 (depression) and SD=–6.35 and 4.70 (anxiety); for the placebo and cognitive therapy group, SD=4.27 and 4.91 (depression) and SD=–4.40 and 5.66 (anxiety); and for the placebo alone group, SD=4.09 and 6.23 (depression) and SD=4.45 and 6.70 (anxiety).

FIGURE 2. Life Satisfaction and Social Interaction Mean Scores at Baseline and After 12 Weeks Of Treatment for 94 Dysthymic Patients Who Received Sertraline and Cognitive Group Therapy, Sertraline Alone, Cognitive Group Therapy and Placebo, or Placebo Alonea

aThe standard deviations for the groups ranged from 0.84 to 1.28 for life satisfaction and from 16.04 to 21.21 for social interaction. For nondepressed control subjects, life satisfaction scores at baseline and after 12 weeks were 5.33 (SD=1.27) and 5.43 (SD=1.09), respectively, whereas social interaction scores were 81.54 (SD=13.81) and 79.68 (SD=16.30).

1. John JB, Wilcox C: A comparison of fluoxetine, imipramine, and placebo in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1985; 46:26–31Google Scholar

2. Feighner JP, Boyer WF: Paroxetine in the treatment of depression: a comparison with imipramine and placebo. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53(Feb suppl):44–47Google Scholar

3. Ives JL, Heym J: Antidepressant agents. Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry 1989; 24:21–29Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Andreasen NC, Black DW: Somatic treatments, in Introductory Textbook of Psychiatry, 2nd ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 655–700Google Scholar

5. Scott J: Cognitive therapy of affective disorders: a review. J Affect Disord 1996; 37:1–11Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Andrews G: The evaluation of psychotherapy. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 1991; 4:379–383Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Dobson K: A meta-analysis of the efficacy of cognitive therapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 1989; 57:414–419Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Teasdale JD, Segal Z, Williams JMG: How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behav Res Ther 1984; 33:25–39Google Scholar

9. Roth D, Bielski D, Jones M, Parker W, Osborn G: A comparison of self-control therapy and combined self-control therapy and antidepressant medication in the treatment of depression. Behavior Therapy 1982; 13:133–144Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Murphy GE, Simons AD, Wetzel RD, Lustman PJ: Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy singly and together in the treatment of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:33–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Beck AT, Hollon SD, Young JE, Bedrosian RC, Budenz D: Treatment of depression with cognitive therapy and amitriptyline. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:142–148Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Depression in Primary Care, vol 2: Treatment of Major Depression: DHHS Publication AHCPR 93-0551. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Depression Guideline Panel, 1993Google Scholar

13. Wexler BE, Cicchetti DV: The outpatient treatment of depression: implications of outcome research for clinical practice. J Nerv Mental Dis 1992; 180:277–286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Evans M, Hollon S, DeRubeis R, Piasecki J, Grove W, Garvey M, Tuason V: Differential relapse following cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:802–808Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Fava GA, Grandi S, Zielezny M, Rafanelli C, Canestrari R: Four-year outcome for cognitive behavioral treatment of residual symptoms in major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:945–947Link, Google Scholar

16. Scott MJ, Stradling SG: Group cognitive therapy for depression produces clinically significant reliable change in community-based settings. Behav Psychother 1990; 18:1–19Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Stravynski A, Verreault R, Gaudettte G, Langlois R, Gagnier S, Larose M: The treatment of depression with group behavioral-cognitive therapy and imipramine. Can J Psychiatry 1994; 39:387–390Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Manning DW, Frances AJ: Group psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy of depression, in Combined Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy for Depression. Edited by Manning DW, Frances AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990, pp 67–111Google Scholar

19. Salvendy JT, Joffe R: Antidepressants in group psychotherapy. Int J Group Psychother 1991; 41:465–480Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Rush AJ, Watkins JT: Group versus individual cognitive therapy: a pilot study. Cognitive Therapy Res 1981; 5:95–103Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Wierzbecki M, Bartlett TS: The efficacy of group and individual cognitive therapy for mild depression. Cognitive Therapy Res 1987; 11:337–342Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Covi L, Lipman S: Cognitive behavioral group psychotherapy combined with imipramine in major depression. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23:173–176Medline, Google Scholar

23. Paykel ES: Psychological therapies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89:35–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Markowitz JC: Psychotherapy of dysthymia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1114–1121Google Scholar

25. Thase ME, Fava M, Halbreich U, Kocsis JH, Koran L, Davidson J, Rosenbaum J, Harrison W: A placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial comparing sertraline and imipramine for the treatment of dysthymia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:777–784Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Baldwin D, Rudge S, Thomas S: Dysthymia: options in pharmacotherapy. CNS Drugs 1995; 4:422–431Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Akiskal HS: Towards a definition of dysthymia: boundaries with personality and mood disorders, in Dysthymic Disorders. Edited by Burton SW, Akiskal HS. London, Gaskell, 1990, pp 1–12Google Scholar

28. Millon T: Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory—II. Minneapolis, National Computer Services, 1987Google Scholar

29. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorin P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Herguerta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(Suppl 20): 22–33Google Scholar

30. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar

35. Mason BJ, Kocsis JH, Leon AC, Thompson S, Frances AJ, Morgan RO, Parides MK: Measurement of severity and treatment response in dysthymia. Psychiatr Annals 1993; 23:625–631Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Kanner AD, Coyne JC, Schaefer C, Lazarus RS: Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. J Behav Med 1981; 4:1–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Ravicki DA, Turner R, Brown R, Martindale JJ: Batelle Quality of Life Scale. Qual Life Res 1992; 1:257–266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Beckham EE, Adams RL: Coping behavior in depression: report on a new scale. Behav Res Ther 1984; 22:71–75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Hollon SD, Shaw BF: Group cognitive therapy for depressed patients, in Cognitive Therapy of Depression. Edited by Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. New York, Guilford Press, 1979, pp 328–353Google Scholar

40. McCullough JP: Cognitive-behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy: an interactional treatment approach for dysthymic disorder. Psychiatry 1984; 47:234–250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Hellerstein DJ, Yanowitch P, Rosenthal J, Samstag LW, Maurer M, Kasch K, Burrows L, Poster M, Cantillon M, Winston A: A randomized double-blind study of fluoxetine versus placebo in the treatment of dysthymia. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1169–1175Google Scholar

42. Friedman RA, Markowitz JC, Parides M, Kocsis JH: Acute response of social functioning in dysthymic patients with desipramine. J Affect Disord 1995; 34:85–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Kocsis JH, Zisook S, Davidson J, Shelton R, Yonkers K, Hellerstein DJ, Rosenbaum J, Halbreich U: Double-blind comparison of sertraline, imipramine, and placebo in the treatment of dysthymia: psychosocial outcomes. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:390–395Link, Google Scholar

44. Marin DB, Kocsis JH, Frances AJ, Parides M: Desipramine for the treatment of “pure” dysthymia versus “double” depression. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1079–1080Google Scholar

45. Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Quitkin FM, Rabkin J, Harrison W, Wager S, Nunes S, Ocepek-Welikson K, Tricamo E: Chronic depression: response to placebo, imipramine, and phenelzine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:391–396Medline, Google Scholar

46. Versiani M, Nardi AE, Figueira IL, Stabl M: Tolerability of moclobemide, a new reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase-A, compared with other antidepressants and placebo. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1990; 360:24–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Petursson H: Studies of reversible and selective inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A in dysthymia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1995; 386:36–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Vallejo J, Gasto C, Catalan R, Salamero M: Double blind study of imipramine versus phenelzine in melancholias and dysthymic disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 151:639–642Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Hellerstein DJ, Samstag LW, Cantillon M, Maurer M, Rosenthal J, Yanowitch P, Winston A: Follow-up assessment of medication-treated dysthymia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1996; 20:427–442Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Ravindran AV, Bialik RJ, Lapierre YD: Primary early onset dysthymia, biochemical correlates of the therapeutic response to fluoxetine, 1: platelet monoamine oxidase and the dexamethasone suppression test. J Affect Disord 1994; 31:111–117Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Ravindran AV, Griffiths J, Waddell C, Anisman H: Stressful life events and coping styles in relation to dysthymia and major depressive disorder: variations associated with alleviation of symptoms following pharmacotherapy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1995; 19:637–653Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Baumhackl U, Biziere K, Fischbach R, Geretsegger C, Hebenstreit G, Radmayr E, Stabl M: Efficacy and tolerability of moclobemide compared with imipramine in depressive disorder (DSM-III): an Austrian double-blind multicentre study. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1989; 6:78–83Medline, Google Scholar

53. Botte L, Evrard JL, Gilles C, Stenier P, Wolfrum C: Controlled comparison of RO 11-1163 (moclobemide) and placebo in the treatment of depression. Acta Psychiatr Belg 1992; 92:355–369Medline, Google Scholar

54. Duarte A, Mikkelsen H, Delini-Stula A: Moclobemide versus fluoxetine for double depression: a randomized double-blind study. J Psychiatr Res 1996; 30:453–458Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Lecrubier Y, Guelfi JD: Efficacy of reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase-A in various forms of depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990; 82:18–23Crossref, Google Scholar

56. Versiani M, Amrein R, Stabl M: Moclobemide and imipramine in chronic depression (dysthymia): an international double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. International Collaboration Study Group. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12:183–193Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Bakish D, Lapierre YD, Weinstein R, Klein J, Wiens A, Jones B, Horn E, Browne M, Bourget O, Blanchard A: Ritanserin, imipramine and placebo in the treatment of dysthymic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:409–414Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Bersani G, Pozzi F, Marini S, Grispini A, Pasini A, Ciani N:5-HT2 receptor antagonism in dysthymic disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled study with ritanserin. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 83:244–248Google Scholar

59. Ravindran A, Wiseman R: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in the treatment of outpatients with dysthymia, in 1997 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1997, p 191Google Scholar

60. Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ: Placebo-psychotherapy combinations: inappropriate representations of psychotherapy in drug-psychotherapy comparative trials. Psychol Bull 1981; 90:467–477Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Padesky CA, Greenberg D: Clinician’s Guide to Mind Over Mood. New York, Guilford Press, 1995Google Scholar

62. Alford BA, Beck AT: Cognitive theory as an integrative theory for clinical practice, in The Integrative Power of Cognitive Therapy. New York, Guilford Press, 1997, pp 94–112Google Scholar

63. Rachman S: The evolution of cognitive behaviour therapy, in Science and Practice of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Edited by Clark DM, Fairburn CG. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1997, pp 3–26Google Scholar

64. Weissman MM: Psychotherapy in the maintenance treatment of depression. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:42–50Crossref, Google Scholar

65. Fava GA, Grandi S, Zielezny M, Canestrari R, Morphy MA: Cognitive behavioral treatment of residual symptoms in primary major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1295–1299Google Scholar

66. Blackburn IM, Moore RG: Controlled acute and follow up trial of cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy in out-patients with recurrent depression. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:328–334Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Walker V, Streiner DL, Novosel S, Rocchi A, Levine MAH, Dean DM: Health-related quality of life in patients with major depression who are treated with moclobemide. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 15(Aug suppl 2):60S–67SGoogle Scholar

68. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. JAMA 1989; 262:914–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Friedman RA: Social impairment in dysthymia. Psychiatr Annals 1993; 23:632–637Crossref, Google Scholar

70. Hellerstein DJ, Little SAS: Current perspectives on the diagnosis and treatment of double depression. CNS Drugs 1996; 5:344–357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Thase ME, Rush AJ: Treatment-resistant depression, in Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. Edited by Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ. New York, Raven Press, 1995, pp 1081–1097Google Scholar

72. Ramana R, Paykel ES, Cooper Z, Hayhurst H, Saxty M, Surtees PG: Remission and relapse in major depression: a two-year prospective follow-up study. Psychol Med 1995; 25:1161–1170Google Scholar

73. Fawcett J: Antidepressants: partial response in chronic depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1994; 26:37–41Medline, Google Scholar

74. Kanfer FH: Motivation and emotion in behavior therapy, in Advances in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. Edited by Dobson KS, Craig KD. London, Sage Publications, 1996, pp 1–30Google Scholar

75. Sanderson WC: Cognitive behavior therapy. Am J Psychother 1997; 51:289–292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar