Differences Between Clinical and Research Practices in Diagnosing Borderline Personality Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: It has been reported that clinicians are less inclined than researchers to use direct questions in ascertaining the presence of personality disorders, and questions have been raised about the validity of research on personality disorders in which diagnoses are based on semistructured diagnostic interviews. This study examined the influence of assessment method on the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. METHOD: Diagnoses of borderline personality disorder derived from structured and unstructured clinical interviews were compared in two groups of psychiatric outpatients seen in the same practice setting. Five hundred individuals presenting to a general adult psychiatric practice for an intake appointment underwent a routine unstructured clinical interview. After the completion of that study, the method of conducting diagnostic evaluations was changed, and 409 individuals were interviewed with the borderline personality disorder section of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality. RESULTS: Individuals in the structured interview group were significantly more often diagnosed with borderline personality disorder than individuals in the clinical group. When information from the structured interview was presented to the clinicians, borderline personality disorder was much more likely to be diagnosed by them. CONCLUSIONS: The method used to assess borderline personality disorder has a great impact on the frequency with which it is diagnosed. Without the benefit of detailed information from a semistructured diagnostic interview, clinicians rarely diagnose the disorder during a routine intake evaluation. Providing the results of a semistructured interview to clinicians prompts them to diagnose borderline personality disorder much more frequently. This is inconsistent with the notion that personality disorder diagnoses based on semistructured interviews are not viewed as valid by clinicians.

Since the publication of DSM-III, research in the area of personality disorders has greatly increased (1). In part, research in this area was facilitated by the development of semistructured diagnostic interviews that increased the reliability of assessing the DSM personality disorders (2, 3). Recently, Westen (4) called into question the validity of personality disorder research that is based on these semistructured diagnostic interviews. He noted that the semistructured research interview method, which relies on direct questions to ascertain the presence or absence of personality disorder criterion symptoms, is at variance with the method clinicians use to diagnose personality disorders. That is, clinicians use a longitudinal perspective to determine the presence or absence of a personality disorder, and their judgments are based on the real-life vignettes patients describe during the course of treatment and the behavior and attitudes patients display during treatment sessions. The results of a national survey asking clinicians to rate the importance of different methods used to diagnose personality disorders supported Westen’s hypothesis that clinicians and researchers use different approaches in making these diagnoses (4).

A comparison of rates of personality disorder in studies using clinical evaluations and research assessments suggests that more diagnoses are made when semistructured diagnostic interviews are used. Oldham and Skodol (5) examined the rate of DSM-III personality disorders in 129,286 inpatients and outpatients seen in the New York State mental health system during a 1-year period and found that 11% were diagnosed with a personality disorder. They concluded that personality disorders were not being systematically diagnosed in these patients. Koenigsberg and colleagues (6) found that in a mixed group of patients from inpatient, outpatient, consultation-liaison, and emergency services, 26% were diagnosed with a specific personality disorder (36% had a personality disorder if mixed and atypical personality disorders were included). In contrast, in the only study to administer a standardized personality disorder interview to an unselected consecutive series of patients (7), 81% of outpatients were diagnosed as having a DSM-III-defined personality disorder. Because of the marked differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between study samples, it is not possible to determine how much of the difference in diagnostic rates is due to the method of assessment and how much is due to true differences in the samples. We are not aware of any studies that have compared the research and clinical approaches to making personality disorder diagnoses in patients drawn from the same population.

In this study from the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnosis and Services project, we examined the influence of assessment method on the occurrence of borderline personality disorder. The rate of borderline personality disorder was compared in two large groups of patients drawn from the same practice setting. In the first group, diagnoses were based on a standard unstructured clinical interview; in the second group, diagnoses were based on a semistructured interview. It was predicted that the rate of borderline personality disorder would be higher in the group of patients who received a semistructured diagnostic interview. We also examined whether clinicians would diagnose the disorder more frequently if they were presented with the results of a standardized interview. We hypothesized that the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder during the initial evaluation is influenced by the amount of information clinicians have available to them at the interview, and if clinicians are provided with information indicative of a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, then the diagnosis will be made.

METHOD

One thousand patients were evaluated in the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry outpatient practice. This private practice group primarily treats individuals with medical insurance (including Medicare but not Medicaid) on a fee-for-service basis, and it is distinct from the hospital’s outpatient residency training clinic that primarily serves lower-income, uninsured, and medical assistance patients.

Before the initial evaluation, all patients were asked to complete a 116-item, self-administered symptom questionnaire as part of their initial paperwork. The clinical study group consisted of 500 patients who successfully completed this questionnaire. Because the validity of the symptom questionnaire was being investigated as part of another project, the clinicians were blind to the patients’ responses on the questionnaire.

After the completion of the first study, the method of conducting initial diagnostic evaluations was changed. Five hundred patients were interviewed by a diagnostic rater who administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P) (8), and the borderline personality disorder section of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (9). The results of this interview were presented to a psychiatrist who finished the evaluation. The borderline personality disorder section of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality was added to the SCID-P interview after 91 patients had already participated in the project; thus, only 409 patients were interviewed with both measures. These patients are subsequently referred to as the structured interview group. The Rhode Island Hospital institutional review committee approved the research protocol, and all patients provided informed, written consent.

In the clinical group, almost all (96%, N=480) diagnostic evaluations were conducted by board-certified or board-eligible psychiatrists. Clinical nurse specialists or master’s-level social workers under the supervision of a psychiatrist conducted the other evaluations. Diagnoses were based on DSM-IV criteria. Clinicians completed a standardized intake form modeled on the Initial Evaluation Form of Mezzich and colleagues (10). On the last page of the five-page form, the clinician recorded the patient’s DSM-IV multiaxial diagnoses. Research assistants recorded the results of the clinician’s diagnostic evaluation written on the last page of the intake form and collected demographic information from the narrative.

In the study involving the structured interviews, when patients called to schedule their initial appointments, they were told that they would be interviewed by two people—first by a diagnostic rater, who would conduct a comprehensive evaluation, and then by a psychiatrist. After administration of the SCID-P and the borderline personality disorder section of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality, the rater presented the case to a psychiatrist who reviewed the findings of the evaluation with the patient. The clinicians then completed the same standardized intake form, and their diagnoses were abstracted in the same manner as was done for the first 500 patients.

Six diagnostic raters were used to administer the SCID-P and the borderline personality disorder section of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality. The raters included the authors of this paper, each of whom has extensive experience administering research diagnostic interviews. The other four raters were research assistants with college degrees in the social or biological sciences. One of these four raters had more than 6 years’ experience administering the SCID-P and had previously trained other research assistants in its use. The other three received 3 months of training during which they observed at least 20 interviews, and they were observed and supervised in their administration of more than 20 evaluations. At the end of the training period, these three raters were required to demonstrate exact, or nearly exact, agreement with a senior diagnostician on five consecutive evaluations. During the course of the study, joint-interview diagnostic reliability information was collected on 17 patients; the kappa coefficient of agreement for the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder was 1.0. Throughout the Methods to Improve Diagnosis and Services project, ongoing supervision of the raters included weekly diagnostic case conferences involving all members of the team.

Toward the end of the clinical study and throughout the structured interview study, patients were given a booklet of questionnaires to complete at home and return by mail. Forty-nine patients in the clinical group and 275 patients in the structured interview group returned the booklet of questionnaires. To examine the clinical similarity of the study groups, the two groups of patients were compared on self-report symptom measures of bulimia (the Eating Disorder Inventory bulimia subscale [11]), social phobia (a brief version of the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale [12] and the Fear Questionnaire social phobia subscale [13]), agoraphobic fears (the Fear Questionnaire agoraphobia subscale [13] and the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory agoraphobia subscale [14]), posttraumatic stress (the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale [15]),obsessive-compulsive behavior (the Obsessive Compulsive Scale [M. Coles et al., unpublished]), cognitions common in generalized anxiety (the Penn State Worry Questionnaire [16]), anxiety symptoms common in panic attacks (the Beck Anxiety Inventory [17]), alcohol use (the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test [18]), drug use (the Drug Abuse Screening Test [19]), hypochondriasis (the Whitely Index [20]), and somatization (the Somatic Symptom Index [21, 22]).Thesescales have been commonly used in research, and their reliability and validity have been well established. The symptom severity measure of depression changed in the two studies. However, the symptom measure that all patients completed before their evaluation included a 21-item depression section, and this subscale was used to compare the two groups.

We used t tests to compare the groups on continuously distributed variables. Categorical variables were compared by means of the chi-square statistic or with the use of Fisher’s exact test if the expected value in any cell of a two-by-two table was less than 5.

RESULTS

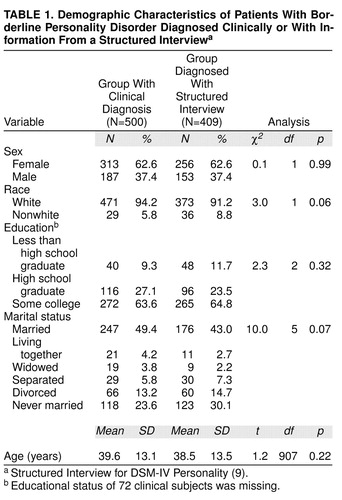

The demographic characteristics of the two groups were quite similar (Table 1). The majority of both groups were white, female, high school graduates, and married or never married. The patients in the two groups were also compared on the self-report symptom severity measures, and there were no significant differences between the groups.

The rate of borderline personality disorder diagnoses was significantly higher in the structured interview group than in the clinical group (14.4%, N=59, versus 0.4%, N=2; χ2=70.69, df=1, p<0.001). The 14.4% frequency of borderline diagnoses in the structured interview group represents the diagnostic rate according to the borderline personality disorder section of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality. The clinicians were not obligated to agree with the diagnoses made by the research interviews. We reviewed the clinical charts of 392 of the 409 patients interviewed with the borderline personality disorder section of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality and abstracted the diagnoses recorded in the patients’ clinical records. Thirty-six (9.2%) of these patients either were diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (N=27) or had borderline personality disorder ruled out (N=9) by the intake clinician. Thus, the frequency of borderline diagnoses assigned by the clinicians was significantly increased when the information from the interview was presented to them before they made their evaluations (9.2% versus 0.4%; χ2=31.97, df=1, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

As expected, the rate of borderline personality disorder diagnoses was higher when the diagnosis was based on a semistructured diagnostic interview than when it was based on an unstructured clinical interview. In fact, clinicians were very reluctant to diagnose borderline personality disorder during their routine intake diagnostic evaluations. This is consistent with the results of Westen’s survey of clinicians’ diagnostic practices (4), which found that clinicians rely on their longitudinal observations to make personality disorder diagnoses. However, inconsistent with Westen’s hypothesis that clinicians rely on longitudinal observation to make these diagnoses, we found that clinicians more frequently diagnosed borderline personality disorder during the initial evaluation when the results of the research interview were presented to them. If clinicians relied on longitudinal observations and considered information based on the direct-question approach of research interviews to be irrelevant or invalid, then being presented with the results from the borderline personality disorder section of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality should not have influenced the rate at which they diagnosed borderline personality disorder. Perhaps the issue in diagnosing personality disorders is not so much the need for longitudinal observation but the need for more time to conduct a comprehensive intake evaluation. Diagnostic evaluations are time-limited, and initially it is more important to determine the axis I diagnosis than an axis II diagnosis, because axis I pathology will have a more immediate effect on treatment planning.

A potential criticism of the diagnostic approach taken in the present study is that patients were interviewed upon presentation for treatment, when they were rarely euthymic. We are aware of the well-known pathologizing effect of psychiatric state on personality (3); nevertheless, we chose this time for assessment because we were interested in the clinical significance of personality pathology, and the sooner a clinician was aware of the presence of borderline personality disorder, the more likely this information could be used for treatment planning. Second, if we had waited to assess personality disorders after symptom improvement, we would have disproportionately excluded patients with borderline personality disorder from our study group, because the presence of personality pathology predicts poorer outcome (23). Ultimately, the onus will be on us to demonstrate that our diagnostic approach is valid. However, a large literature examining the treatment, prognostic, familial, and biological correlates of personality disorders already suggests that diagnosis of personality disorder in this manner is valid (24, 25).

Westen (4) critiqued the research literature on personality disorder on several fronts. As already discussed, he noted the marked variance between the clinical and research approaches to diagnosing personality disorders. Moreover, he indicated that there was a marked discrepancy in the product of clinical and research interviews. That is, researchers make multiple axis II diagnoses without prioritizing them, whereas clinicians usually assign only one diagnosis. Westen is correct in noting that in studies using semistructured research interviews to diagnose personality disorder, the majority of patients with a personality disorder are given more than one diagnosis (26), whereas clinicians tend to assign only one diagnosis. However, it is erroneous to conclude that this necessarily reflects a problem with the research method. It is equally plausible to conclude that the clinical evaluation is not sufficiently thorough. A review of the literature on detection of comorbidity of axis I disorders suggests that clinicians underrecognize diagnostic comorbidity. Three studies of axis I diagnostic comorbidity rates based on clinical evaluations (27–29) found that approximately 25% of patients were diagnosed with two or more disorders. This rate is one-half to one-third the rates found in studies of psychiatric patients, as well as general population residents in the community, when diagnoses are based on semistructured interviews (30–41). Thus, Westen’s suggestion that there is a problem with current personality disorder research because of the high rate of multiple diagnoses can be interpreted in either of two ways. As Westen indicated, it might reflect a problem with a method of diagnosis that mindlessly casts too wide a net and fails to distinguish clinically relevant from irrelevant pathology. If true, then the problem of overdiagnosing comorbidity exists for both axis II and axis I assessments. Alternatively, it could be that there is a problem with the unstructured routine clinical evaluation and that clinicians do not thoroughly explore the presence of comorbid pathology after documenting the diagnosis responsible for the patient’s chief complaint.

Received Sept. 8, 1998; revisions received Dec. 11, 1998, and March 22, 1999; accepted April 1, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University School of Medicine, Rhode Island Hospital, Providence. Address reprint requests to Dr. Zimmerman, Bayside Medical Center, 235 Plain St., Providence, RI 02905; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grant MH-48732 to Dr. Zimmerman. The authors thank Sharon Hunter, Ava Nepaul, Melissa Torres, and Sharon Younkin for assistance in collecting the data.

|

1. Blashfield RK, McElroy RA: The 1985 journal literature on the personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 1987; 28:536–546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Perry JC: Problems and considerations in the valid assessment of personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1645–1653Google Scholar

3. Zimmerman M: Diagnosing personality disorders: a review of issues and research methods. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:225–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Westen D: Divergences between clinical and research methods for assessing personality disorders: implications for research and the evolution of axis II. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:895–903Link, Google Scholar

5. Oldham JM, Skodol AE: Personality disorders in the public sector. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42:481–487Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Koenigsberg HW, Kaplan RD, Gilmore MM, Cooper AM: The relationship between syndrome and personality disorder in DSM-III: experience with 2,462 patients. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:207–212Link, Google Scholar

7. Alneas R, Torgersen S: The relationship between DSM-III symptom disorders (axis I) and personality disorders (axis II) in an outpatient population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 78:485–492Crossref, Google Scholar

8. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

9. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M: Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality: SIDP-IV. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

10. Mezzich JE, Dow JT, Rich CL, Costello AJ, Himmelhoch JM: Developing an efficient clinical information system for a comprehensive psychiatric institute, II: initial evaluation form. Behavior Res Methods, Instruments, and Computers 1981; 13:464–478Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J: Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eating Disord 1983; 2:15–34Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Leary MR: A brief version of the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Personality and Social Psychol Bull 1983; 9:371–375Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Marks IM, Mathews AM: Brief standard self-rating for phobic patients. Behav Res Ther 1979; 17:263–267Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Turner SM, Beidel DC, Dancu CV, Stanley MA: An empirically derived inventory to measure social fears and anxiety: the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory. Psychol Assessment 1989; 1:35–40Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO: Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 1993; 6:459–473Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD: Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther 1990; 28:487–495Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA: An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:893–897Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Selzer M: The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry 1971; 127:1653–1658Google Scholar

19. Skinner HA: The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addict Behav 1982; 7:363–371Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Pilowsky I: Dimensions of hypochondriasis. Br J Psychiatry 1967; 113:89–93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Othmer E, DeSouza C: A screening test for somatization disorder (hysteria). Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1146–1149Google Scholar

22. Swartz M, Hughes D, George L, Blazer D, Landerman R, Bucholz K: Developing a screening index for community studies of somatization disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1986; 20:335–343Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Reich JH, Green AI: Effect of personality disorders on outcome of treatment. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 179:74–82Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Battaglia M, Torgersen S: Schizotypal disorder: at the crossroads of genetics and nosology. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 94:303–310Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Silk KR (ed): Biological and Neurobehavior Studies of Borderline Personality Disorder. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

26. Widiger TA, Rogers JH: Prevalence and comorbidity of personality disorders. Psychiatr Annals 1989; 19:132–136Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Stangler RS, Printz AM: DSM-III: psychiatric diagnosis in a university population. Am J Psychiatry 1980; 137:937–940Link, Google Scholar

28. Loranger AW: The impact of DSM-III on diagnostic practice in a university hospital. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:672–675Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Mezzich JE, Fabrega H, Coffman GA: Multiaxial characterization of depressive patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1987; 175:339–346Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Barlow DH, DiNardo PA, Vermilyea BB, Vermilyea J, Blanchard EB: Comorbidity and depression among the anxiety disorders: issues in diagnosis and classification. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:63–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Brown TA, Barlow DH: Comorbidity among anxiety disorders: implications for treatment and DSM-IV. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:835–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Cassano GB, Perugi G, Musetti L: Comorbidity in panic disorder. Psychiatr Annals 1990; 20:517–521Crossref, Google Scholar

33. DeRuiter C, Rijken H, Garssen B, VanSchaik A, Kraaimaat F: Comorbidity among the anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disorders 1989; 3:57–68Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Goisman RM, Goldenberg I, Vasile RG, Keller MB: Comorbidity of anxiety disorders in a multicenter anxiety study. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36:303–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Green BL, Lindy JD, Grace MC, Gleser GD: Multiple diagnoses in posttraumatic stress disorder: the role of war stressors. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:329–335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Lesser IM, Rubin RT, Pecknold JC, Rifkin A, Swinson RP, Lydiard RB, Burrows GD, Noyes R, DuPont RL: Secondary depression in panic disorder and agoraphobia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:437–443Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Markowitz JC, Moran ME, Kocsis JH, Frances AJ: Prevalence and comorbidity of dysthymic disorder among psychiatric outpatients. J Affect Disord 1989; 24:63–71Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Sanderson WC, Beck AT, Beck J: Syndrome comorbidity in patients with major depression or dysthymia: prevalence and temporal relationships. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1025–1028Google Scholar

39. Sanderson WC, DiNardo PA, Rapee RM, Barlow DH: Syndrome comorbidity in patients diagnosed with a DSM-III-R anxiety disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 1990; 3:308–312Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Schwalberg MD, Barlow DH, Alger SA, Howard LJ: Comparison of bulimics, obese binge eaters, social phobics, and individuals with panic disorder on comorbidity across DSM-III-R anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101:675–681Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Sierles FS, Chen J-J, McFarland RE, Taylor MA: Posttraumatic stress disorder and concurrent psychiatric illness: a preliminary report. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1177–1179Google Scholar