Effects of ADHD, Conduct Disorder, and Gender on Substance Use and Abuse in Adolescence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The relationships of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder, and gender to substance abuse were studied in a large population-based sample of adolescent twins. METHOD: Structured interviews were administered to 626 pairs of 17-year-old twins (674 girls and 578 boys) and their mothers to generate lifetime psychiatric diagnoses, and computerized measures of current substance use were obtained. Hierarchical logit analyses were performed to assess the independent effects of ADHD, conduct disorder, and gender on current substance use, frequency of substance use, and DSM-III-R diagnoses of substance use disorders. RESULTS: Conduct disorder was found to increase the risk of substance use and abuse in adolescents regardless of gender. In contrast, independent of its association with conduct disorder, an ADHD diagnosis did not significantly increase the risk of substance use problems. CONCLUSIONS: This study found no significant gender differences in the effects of ADHD and conduct disorder on substance use and abuse, although there was some suggestion that girls with ADHD might be at slightly higher risk than boys for substance abuse. In addition, increased risk of substance abuse among adolescents with conduct disorder may be primarily confined to those with persistent conduct disorder.

According to DSM-IV, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) occurs in about 3%–5% of school-age children, with a lower prevalence in girls than in boys. Substantial concern has been expressed about the possible connection of ADHD to substance use and abuse, particularly during adolescence, which is an important developmental stage for the foundation of problems with substance use. A considerable literature on the risk of substance use and abuse among ADHD probands has accumulated. The studies reported in these articles can be divided into three general categories: 1) long-term prospective studies of hyperactive children that determined their risk of ubstance use disorders, 2) studies of adolescents undergoing substance abuse treatment or jailed for delinquency that examined rates of ADHD and comorbid substance use disorders, and 3) studies of adults with a current diagnosis of ADHD that assessed the comorbidity of substance use disorders. Common to all of these study methods was the frequent use of all-male or unbalanced-gender designs. Because a mere 10% of a study group typically represented female subjects with the disorder, data from female subjects were usually combined with those from male subjects for purposes of analysis. Subsequently, it was often reported that no differences between male and female subjects were found, although the small size of the female group would make any differences quite difficult to detect.

Prospective studies of hyperactive children (1–5) have reported that the association between ADHD and substance use disorders, when studied prospectively, appears to be almost entirely mediated through conduct disorder (6). Comorbid conduct disorder has been reported in 30%–50% of ADHD cases (7). Although these studies have been crucial in advancing research in this area, they have several limitations. First, many used study groups who were initially identified as “hyperactive” a number of years ago, before the concept of ADHD had been fully developed, which makes comparison with present-day populations difficult. Second, many did not report DSM-defined diagnoses based on structured interviews.

The studies of hospitalized or jailed adolescents (8–10) have helped focus attention on the severity of impairment suffered by some adolescents with ADHD, since these studies reported high rates of comorbid ADHD, conduct disorder, and substance use disorders. However, they obviously sampled a nonrepresentative portion of the overall population, biased toward extreme cases with more externalizing symptoms.

Finally, studies of adults with ADHD have often found a direct connection between ADHD and substance use disorders, adding to the controversy in this area (11–13). Notably, Biederman et al. (12) reported that adults with ADHD have an increased risk of substance use disorders independent of psychiatric comorbidity. These studies may or may not bear on the question of adolescents’ risk of substance abuse. Since only about 30% of persons with ADHD continue to have the diagnosis into adulthood (13), it seems probable that adults who still have ADHD may represent special cases of the disorder.

Another critical concern not addressed in most of these studies is how girls with ADHD may differ from boys with ADHD in their vulnerability to substance abuse problems. Gaub and Carlson (14), in their review and meta-analysis of gender issues in ADHD research, concluded that “the current literature leaves largely unanswered many of the most critical questions regarding the nature of ADHD in girls” (p. 1044); girls’ risk of substance abuse and other disorders is certainly among these questions. There also appears to be a dearth of large-scale, population-based studies of the development of substance use and abuse in study groups that include female subjects with ADHD and conduct disorder. Gaub and Carlson called attention to the issue of population-based versus clinic-based study groups, since their meta-analysis suggested that in nonreferred groups, girls with ADHD may show less impairment than boys with ADHD. Further, they estimated that community samples show a 3:1 male-to-female ratio in cases of ADHD, while clinic-referred cases are more likely to have a 6:1 or even 9:1 male-to-female ratio. Therefore, study groups that rely on clinic-referred girls are unlikely to represent the true nature of the disorder in the population.

The purpose of the present study was to address the concerns outlined above by exploring the relationship of ADHD and conduct disorder to substance abuse in a gender-balanced sample of adolescents. The Minnesota Twin Family Study serves this purpose well because of the large size of the population-based sample, the administration of structured clinical interviews to generate lifetime diagnoses, and the use of a computerized substance use measure to encourage frank responses regarding current substance use. Consistent with previous research on groups of male adolescents, we expected that a comorbid diagnosis of conduct disorder would account for a substantial portion of any apparent relationships between ADHD and substance use.

METHOD

The subjects were 674 girls and 578 boys from 626 reared-together twin pairs who participated in the Minnesota Twin Family Study with their parents. The Minnesota Twin Family Study is a longitudinal study designed to identify genetic and environmental factors that influence the development of substance abuse and associated psychological disorders. The study uses a population-based twin ascertainment method in which all twins born in the state of Minnesota are identified by public birth records. The initial assessment is conducted during the year the twins become 11 years old or 17 years old. For the present investigation, twins from the 17-year-old age group were used (mean age=16.93 years, SD=0.57). Male twins were identified from birth records for the years 1972–1978, and female twins for the years 1975–1979. We were able to locate over 90% of all sets of twins born in these years in which both members were still living. Families were excluded from participation if the twins had been adopted, lived more than a day’s drive from Minneapolis, or had a physical or intellectual disability that precluded their completing our assessment. Of the eligible families with twins, approximately 17% declined our invitation to participate. After a complete description of the study was given, written informed consent was obtained from the parents, and written assent was obtained from the twins.

The mean number of years of education was 13.7 (SD=1.9) for the biological mothers of the twins and 14.2 (SD=2.3) for the biological fathers. The mean occupational status (as assessed with the Hollingshead system) was 4.2 (SD=2.0) for the mothers and 3.7 (SD=1.8) for the fathers (a Hollingshead rating of 4 corresponds to such jobs as data entry operator, retail clerk, and bank teller). Consistent with Minnesota demographics for the birth years sampled, the overwhelming majority of both mothers and fathers (98%) were Caucasian.

Measures

All twins and mothers were interviewed separately by different interviewers regarding a variety of DSM-III-R disorders, including those used for the present investigation. Interviewers had a minimum of a bachelor’s degree in psychology and went through extensive training. Maternal reports of ADHD, conduct disorder, and substance disorder symptoms were obtained with the use of the parent version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—Revised (15), which was modified for this study. An adolescent version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—Revised was used to interview twins regarding symptoms of ADHD. Twins were assessed for conduct disorder (symptoms before age 15) and adult antisocial behavior (symptoms of antisocial personality disorder appearing since age 15) with a structured interview developed by the Minnesota Twin Family Study, and they were assessed for substance abuse and dependence with an expanded version of the substance abuse module of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (16). As a supplement to the diagnostic interviews, information on substance use was obtained through a computer-administered substance use and abuse questionnaire. This questionnaire was self-administered in a sound-dampened room, to provide maximum privacy for adolescents reporting on their substance use histories.

Following the interview, lifetime DSM-III-R diagnoses were determined by teams of two advanced clinical psychology graduate students who reviewed coded interviews and audiotapes. Diagnoses were assigned on the basis of consensus between the two diagnosticians. To estimate the reliability of the consensus process, interviews of over 600 subjects from the Minnesota Twin Family Study were selected to ensure adequate representation of different types of subjects and diagnoses. These interviews were then independently reevaluated by a second team. Interteam agreement was assessed with the kappa statistic. Kappas were 0.84 for ADHD, 0.75 for conduct disorder, and 0.79 for adult antisocial behavior. Kappas for all substance disorders were 0.92 or greater.

To achieve the most accurate classification of four groups based on the presence or absence of ADHD and conduct disorder (i.e., subjects with ADHD plus conduct disorder, those with ADHD only, those with conduct disorder only, and comparison subjects without these diagnoses), three levels of diagnostic certainty were used: definite (all diagnostic criteria satisfied), probable (one symptom short of a definite diagnosis), and possible (used for ADHD only; two symptoms short of a definite diagnosis). This resulted in 13.5% (N=78) of the boys and 4.7% (N=32) of the girls in this sample receiving a diagnosis of ADHD (a 2.9:1 male-to-female ratio) and 37.2% (N=215) of the boys and 13.1% (N=88) of the girls receiving a diagnosis of conduct disorder. Both ADHD and conduct disorder were present in 8.7% (N=50) of the boys and 1.2% (N=8) of the girls in the entire sample. The 57.9% (N=335) of the boys and the 83.4% (N=562) of the girls who received neither diagnosis were classified as members of the comparison group. Of the ADHD cases, 48.2% were at the definite level of certainty, and of the conduct disorder cases, 54.1% were at the definite level. Thus, our sample of ADHD and conduct disorder cases used for statistical analysis included both definite and subthreshold cases. This inclusion of both clinical and subclinical cases is supported by findings of other community-based twin studies of ADHD (17) and conduct disorder (18), which have supported viewing these disorders as extremes on behavioral dimensions that vary genetically throughout the population, rather than as discrete disorders.

Current use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana was coded positive if the adolescent reported having used the substances at least a few times during the past 12 months (for alcohol, only use without parental permission was counted). An individual was coded as having a tobacco use, alcohol use, or cannabis use disorder if he or she met all of the DSM-III-R criteria for either abuse of or dependence on the relevant substance. Among substance users, current substance use was recorded as frequent versus occasional by dichotomizing frequency of tobacco use as daily versus nondaily, of alcohol use as weekly versus nonweekly, and of marijuana use as monthly versus nonmonthly. Frequency of use of substances other than tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana was too low to permit meaningful statistical analysis.

Analyses

The relationship of substance use and abuse to ADHD and conduct disorder diagnoses was investigated by using hierarchical logit analysis. Logit analysis is a special type of log linear model that examines the relationship between a dichotomous dependent variable (such as presence or absence of substance abuse) and one or more dichotomous independent variables. Unlike chi-square analysis of categorical data, log linear models provide estimates of the effects of variables on each other, similar to multiple regression models (19).

We completed a separate logit analysis using each substance use and abuse measure as the dependent variable and gender (male or female), ADHD diagnosis (present or absent), and conduct disorder diagnosis (present or absent) as the independent variables. Because of the strong interrelationships among the three independent variables, the significance of effects was assessed sequentially. For each of the three independent variables, two hypotheses were tested: 1) a composite hypothesis that simultaneously tested the significance of all interaction terms that included that variable (e.g., for ADHD, this involved simultaneously testing the significance of the three-way interaction effect and the two two-way interaction effects, ADHD by conduct disorder and ADHD by gender) and 2) a conditional hypothesis that tested the significance of the main effect under the assumption that there were no interaction effects (e.g., for ADHD, this involved testing whether ADHD diagnosis was associated with substance use outcome, provided that there were no interactions between ADHD and the other independent variables). For both hypotheses, interaction and main effects were assessed in a model that included the effects associated with the other independent variables; thus, for example, we investigated the effect of ADHD after taking into account the effects associated with conduct disorder and gender. Only effects significant at p<0.01 (two-tailed) are reported and discussed as being statistically significant, because of the multiple statistical test results we are reporting and in order to minimize the effect of correlated observations arising from the use of data from twins, who were treated in this analysis as individual cases.

RESULTS

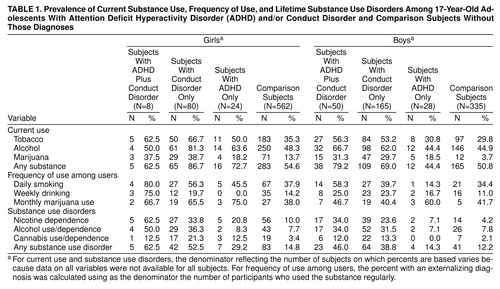

Table 1 presents the prevalence and frequency of current substance use as well as the lifetime prevalence of substance use disorders in our adolescent sample, by diagnostic group and gender. It is notable that the groups defined by a conduct disorder diagnosis (i.e., those with ADHD plus conduct disorder and conduct disorder only) consistently had the highest rates of substance use and abuse by both male and female subjects.

The results of the logit analysis of each of the 11 substance use and abuse variables demonstrate a consistent pattern of findings across multiple outcome measures. None of the composite interaction tests (df=3) were statistically significant at the p<0.01 level. The lack of significant interaction effects indicates that the association of each of the independent variables (ADHD, conduct disorder, or gender) with substance use outcome was not significantly moderated by status on the other two independent variables.

Similarly, none of the main effects of ADHD were statistically significant. Therefore, a diagnosis of ADHD was not significantly associated with substance use and abuse outcomes, once the effects associated with gender and conduct disorder diagnosis had been taken into account. In contrast, the main effect of conduct disorder was significant for 10 of the 11 substance variables (df=1 in each case): current use of tobacco (χ2=54.15, p<0.0001), current use of alcohol (χ2=38.65, p<0.0001), current use of marijuana (χ2=80.85, p<0.0001), current use of any substance (χ2=46.41, p<0.0001), frequency of smoking among smokers (χ2=7.85, p<0.01), frequency of alcohol use among drinkers (χ2=10.21, p=0.001), and the diagnoses of nicotine dependence (χ2=81.46, p<0.0001), alcohol abuse or dependence (χ2=100.15, p<0.0001), cannabis abuse or dependence (χ2=54.02, p<0.0001), and any substance use disorder (χ2=106.63, p<0.0001). This clearly indicates that a diagnosis of conduct disorder is an important predictor of substance use outcome, even after the effects associated with ADHD and gender have been taken into account. There were also three significant main effects of gender (df=1 in each case): current use of tobacco (χ2=6.95, p<0.01), current use of marijuana (χ2=19.77, p<0.0001), and nicotine dependence (χ2=16.14, p<0.0001), which were due to the fact that once the influence of ADHD and of conduct disorder had been taken into account, female gender was associated with a higher risk of some types of substance use.

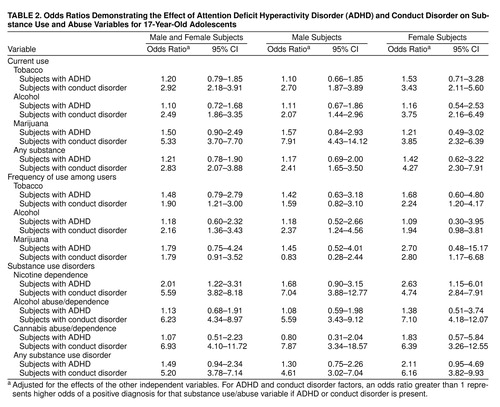

Table 2 shows the odds ratios for the main effects of ADHD and conduct disorder for both genders. Odds ratios were estimated by using logistic regression and were adjusted for the effects associated with the other independent variables. Odds ratios have a null value of 1.0, which indicates that the independent variable tested did not show a consistent association with the dependent variable. In contrast, an odds ratio of 2.0 indicates that the presence of the independent variable was associated with a twofold increase in the odds of the occurrence of the outcome tabulated by the dependent variable. It is clear that when adjusted for the effects of conduct disorder, ADHD diagnosis had little independent effect on substance use and abuse, with the only exception being nicotine dependence, which a diagnosis of ADHD made twice as likely. In contrast, conduct disorder diagnosis had an overwhelmingly strong influence on a wide variety of measures of substance use and abuse. This effect was particularly prominent in the diagnosis of substance use disorders, with the presence of a conduct disorder diagnosis increasing the relative likelihood of these disorders five- and sixfold.

As previously stated, the chi-square values based on the logit analyses indicate that gender did not interact significantly with either an ADHD or a conduct disorder diagnosis to affect substance use or abuse. This means that the association of ADHD and conduct disorder with substance use disorders was not significantly different in girls as compared to boys. Despite this finding, we report odds ratios separately for male and female subjects, since so few studies have looked at the association between disinhibitory psychopathology and substance use outcomes in female study groups. Thus, any consistent pattern of differences between the male and female groups would be of interest, even if not statistically significant.

We also wished to briefly consider the issue of persistence of antisocial behavior over time and its relationship to substance use and abuse. Since conduct disorder symptoms are assessed only for the period up to age 15, while adult antisocial behavior is assessed after age 15, we subdivided the adolescents with conduct disorder into two groups: those with conduct disorder only (127 boys and 55 girls) and those with at least two adult antisocial behavior symptoms (88 boys and 33 girls). Overall, 64.8% of the boys diagnosed with conduct disorder who had adult antisocial behavior and 93.9% of the girls diagnosed with conduct disorder who had adult antisocial behavior had a substance abuse or dependence diagnosis, while only 23.0% of the boys and 27.8% of the girls with conduct disorder only (and not adult antisocial behavior) had a substance use disorder. Therefore, substance use disorders were much more prevalent among adolescents with conduct problems that persisted into late adolescence. Breaking down this finding for specific substances yielded consistently similar results.

DISCUSSION

The results of this investigation—one of the first to extend the study of the effects of ADHD and conduct disorder on substance abuse into a large population-based sample including both genders—are consistent with previous research on male children and adolescents, which suggested that the connection between ADHD and substance use disorders is almost entirely due to a comorbid diagnosis of conduct disorder. We found that independent of conduct disorder, a diagnosis of ADHD has little effect on substance use and abuse outcomes in either gender.

However, although none of the main effects of ADHD were significant at p<0.01, one was significant at p<0.05, indicating a possible effect of ADHD on risk of nicotine dependence (χ2=6.53, df=1). We report this possible finding because it concurs with findings of a recent prospective study of ADHD and cigarette smoking among boys (20), in which ADHD was a significant predictor of cigarette smoking even after control for conduct disorder. There may also be differences between ADHD-affected boys and girls that we were unable to detect. Despite our large sample (1,252 adolescents), the rarity of externalizing disorders among the female subjects meant that the affected female groups were smaller than ideal. Of the 674 girls in the study, we were able to find only 32 who had ADHD. Within these constraints, the odds ratios in Table 2 might be the most sensitive indicators of possible gender differences, inasmuch as the odds ratios were not constrained by the strict p<0.01 standard, which would make only large effects detectable within our small female diagnostic groups. We found that odds ratios were higher in ADHD-affected girls than in ADHD-affected boys for nicotine dependence, cannabis abuse/dependence, and any substance use disorder generally, suggesting that ADHD may put girls at slightly greater risk for these problems than boys.

Clearly, conduct disorder is a powerful factor influencing substance-related outcomes, since it had an impact on 10 of 11 measures of substance use or abuse across genders. This finding has substantial support, since several prospective studies have strongly indicated that conduct problems often precede the development of alcohol and drug problems (21). In addition, empirically based classifications of alcoholism, including a recent cluster analysis of a sample of alcoholic fathers from the Minnesota Twin Family Study (22), have found that alcoholics with onset of alcohol problems at an early age are especially likely to have exhibited childhood aggression and antisocial behavior. Thus, the connection between a conduct disorder diagnosis and early onset of substance problems in males is well documented, although the present study helps document that this finding also holds true for females in a large, population-based study.

It also appears that the adolescents in our study who had conduct disorder and who continued to exhibit antisocial or delinquent behavior after age 15 were much more likely to develop substance problems. This conclusion is also supported by data from fathers in the Minnesota Twin Family Study (23). In addition, in a group of adult male subjects with ADHD who had been followed up since childhood, Mannuzza et al. (24) recently noted that substance disorders in the ADHD probands were heavily concentrated in the subjects who also had antisocial personality disorder. Future research should consider not only the influence of conduct disorder on substance abuse but also whether conduct-disorder-related behaviors persist into late adolescence, since our data suggest that this more persistent form of conduct disorder accounts for most of the relationship of conduct disorder to substance abuse.

There are several limitations to our findings. Our subjects, at age 17, were older than those in many other studies that have addressed the topic of ADHD, conduct disorder, and substance abuse. However, they were still well within with the risk period for developing substance abuse, and other investigators have reported finding increases in the rates of substance use disorders among ADHD probands during late adolescence and early adulthood (1, 24). This suggests that the eventual scope of substance abuse problems in this sample is likely to be underestimated in this report, and we are unable to ascertain at present whether there is any relationship between ADHD and later-onset substance use disorders. As we are in the process of following up this sample at ages 20 and 23, we plan to address this issue in the future.

Another limitation is that we were not able to statistically evaluate the effects of prior treatment with stimulant medications (e.g., methylphenidate) on later substance use problems in our subjects with ADHD, because only 22 (20% of the subjects with ADHD) reported taking these medications. Although there did appear to be a somewhat elevated risk of substance abuse among the subjects with ADHD who were treated with stimulant medications, almost 60% of these subjects also had comorbid conduct disorder. Since this raises the possibility that the presence of conduct disorder could account for the elevated risk of substance use in persons treated with stimulants, future studies evaluating the effect of stimulant treatment on later risk of substance abuse should control for the effects of comorbid conduct disorder.

Received July 21, 1998; revision received Jan. 4, 1999; accepted March 16, 1999. From the Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota. Address reprint requests to Dr. Iacono, Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, Elliott Hall, 75 East River Rd., Minneapolis MN 55455-0344. Supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA-05147) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA-09367).

|

|

1. Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Faraone SV, Weber W, Curtis S, Thornell A, Pfister K, Jetton J, Soriano J: Is ADHD a risk factor for psychoactive substance use disorders? Findings from a four-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:21–29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M: Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:565–576Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Boyle MH, Offord DR, Racine YA, Szatmari P, Fleming JE, Links PS: Predicting substance use in late adolescence: results from the Ontario Child Health Study follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:761–767Link, Google Scholar

4. Lynskey M, Fergusson D: Childhood conduct problems, attention deficit behaviors, and adolescent alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1995; 23:281–302Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Klein R, Mannuzza S: Long-term outcome of hyperactive children: a review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30:383–387Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wilens T, Biederman J: Psychopathology in preadolescent children at high risk for substance abuse: a review of the literature. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1993; 1:207–218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S: Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:564–577Link, Google Scholar

8. Fehon D, Becker D, Grilo C, Walker M, Levy K, Edell W, McGlashan T: Diagnostic comorbidity in hospitalized adolescents with conduct disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1997; 38:141–145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Young S, Mikulich S, Goodwin M, Hardy J, Martin C, Zoccolillo M, Crowley T: Treated delinquent boys’ substance use: onset, pattern, relationship to conduct and mood disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995; 37:149–162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Milin R, Halikas J, Meller J, Morse C: Psychopathology among substance abusing juvenile offenders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30:569–574Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Shekim W, Asarnow R, Hess E, Zaucha K, Wheeler N: A clinical and demographic profile of a sample of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, residual state. Compr Psychiatry 1990; 31:416–425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Milberger S, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV: Psychoactive substance use disorders in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): effects of ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1652–1658Google Scholar

13. Wilens T, Biederman J, Spencer T, Frances R: Comorbidity of attention-deficit hyperactivity and psychoactive substance use disorders. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994; 45:421–423, 435Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Gaub M, Carlson C: Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1036–1045Google Scholar

15. Reich W, Welner Z: Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—Revised: DSM-III-R Version (DICA-R). St Louis, Washington University, 1988Google Scholar

16. Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, Sartorius N, Towle LH: The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1069–1077Google Scholar

17. Levy F, Hay DA, McStephen M, Wood C, Waldman I: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a category or a continuum? Genetic analysis of a large-scale twin study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:737–744Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Slutske WS, Heath AC, Dinwiddie SH, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Dunne MP, Statham DJ, Martin NG: Modeling genetic and environmental influences in the etiology of conduct disorder: a study of 2,682 adult twin pairs. J Abnorm Psychol 1997; 106:266–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Norusis MJ: SPSS for Windows: Base System User’s Guide and Advanced Statistics, Release 6.0. Chicago, SPSS, 1993Google Scholar

20. Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone S, Chen L, Jones J: ADHD is associated with early initiation of cigarette smoking in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:37–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller Y: Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychol Bull 1992; 112:64–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. McGue M, Slutske W, Taylor J, Iacono WG: Personality and substance use disorders, I: effects of gender and alcoholism subtype. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1997; 21:513–520Medline, Google Scholar

23. Elkins IJ, Iacono WG, Doyle AE, McGue M: Characteristics associated with the persistence of antisocial behavior: results from recent longitudinal research. Aggression and Violent Behavior 1997; 2:101–124Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M: Adult psychiatric status of hyperactive boys grown up. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:493–498Link, Google Scholar