Management of Threats of Violence Under California's Duty-to-Protect Statute

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This is the first study to assess clinical practices under one of the new duty-to-protect statutes, some version of which has been passed in many states. In 1985, California enacted a statute enabling psychotherapists to limit their liability when a patient makes a serious threat of violence by 1) making reasonable efforts to warn the victim of the threat and 2) notifying local police. METHOD: The authors examined all duty-to-protect notifications over a 5-year period in San Francisco by reviewing police and court records. RESULTS: Police received only 337 notifications, typically made by nondoctoral staff members at public facilities such as psychiatric hospitals and crisis clinics. Patients most commonly directed their threats toward family members. Of the patients who made threats resulting in notifications, 51% had prior arrest records, and 14% had subsequent arrests. Only 52% of the patients who made threats were civilly committed. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that 1) clinicians rarely discharge the duty to protect in the manner specified by the law, 2) many patients whose threats result in notifications have extensive involvement with the criminal justice system, and 3) family intervention may have clinical relevance in many duty-to-protect situations. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1097–1101)

Court decisions such as the Tarasoff ruling have mandated that when a patient threatens violence, the mental health clinician has a special responsibility to evaluate the patient's dangerousness and to take appropriate actions to protect others from the danger (1). The creation of such a duty to protect has aroused much controversy because of the risks to the treatment relationship associated with breaching confidentiality to disclose such threats (2), the large body of research suggesting that clinicians' ability to predict violence is quite limited (3), and ambiguity about what actions the clinician must undertake to discharge the duty. To clarify clinicians' responsibilities, many states have enacted laws that limit therapists' potential liability if they take specified actions when a patient makes a serious threat against an identifiable victim (4). In California, for example, psychotherapists may limit their liability by both making reasonable efforts to warn the victim of the threat and notifying local police (5). Despite the national significance of the problem, minimal research has been conducted on the evaluation and management of patients who threaten violence in jurisdictions where these new laws are in force. In this report, we describe how clinicians have interpreted the law in a city in California, the first state to enact a duty-to-protect law.

The establishment of a duty of psychotherapists to victims of potentially violent patients has created much controversy among mental health professionals. Following the Tarasoff ruling, several surveys evaluated therapists' opinions about their willingness to breach confidentiality and warn probable victims, their perceived ability to predict violence, and their clinical practices in the care of dangerous patients (6–8). However, no studies have directly measured therapists' actual behavior regarding disclosure of violent threats by their patients, although there have been many hypotheses about what clinicians do when faced with this situation. For example, a textbook of psychiatry states, “It is difficult if not impossible to envision a clinically realistic situation requiring a warning in which involuntary commitment is not also called for, as the levels of danger that are conditions for the two actions are indistinguishable” (9, p. 2762).

In this study, we examined all Tarasoff-type notifications in San Francisco for the first 5 years after passage of California's duty-to-protect statute in 1985. We addressed the following questions: 1) How frequent are such notifications? 2) Which clinicians make the notifications? 3) In which treatment settings do the notifications originate? 4) What are the characteristics of and relationships between the patients who make threats and the persons they threaten? 5) How do the demographic characteristics of patients who make threats that result in notification compare with those of other patients? For the final question, we restricted study to public sector patients because of the absence of any central registry of patients treated outside the public sector.

METHOD

As noted earlier, the 1985 California statute mandates that psychotherapists may discharge their duty to protect by both making reasonable efforts to warn the victim and notifying the police. In San Francisco, a city of about 750,000 residents, all Tarasoff threats between 1986 (the first year the statute was implemented) and 1990 were referred to a specialized psychiatric liaison unit in the San Francisco Police Department. Our study involved review of all such duty-to-protect notifications to the police between 1986 and 1990. For each case, we reviewed a standard form containing information about the characteristics of both perpetrator and victim and a narrative summary of the incident. We obtained arrest histories from the computerized police database.

We collected information about the rate of involuntary civil commitments in San Francisco from the county health records. To place the rate of civil commitments following Tarasoff notifications in context, we also examined 1 year's total number of involuntary civil commitments based on dangerousness to others. We also compared the demographic characteristics of the public sector patients for whom reports were made with those of other public sector patients treated in the same time period, using chi-square analyses, corrected for continuity where appropriate.

RESULTS

Rates of Notifications

During the first 5 years after implementation of the duty-to-protect statute in 1986, 337 notifications were made. There was an increase in the frequency of notifications for the first 3 years, with six in 1986, 51 in 1987, and 81 in 1988, after which the rate of notifications leveled off. Ninety-seven notifications were made in 1989 and 102 in 1990. Of the 337 patients who made threats that resulted in notifications, 52% (N=175) were subsequently placed on civil commitments.

The patients whose threats led to notifications, however, represented a small proportion of the total number of patients in San Francisco who made threats during the same time period. In 1988, for example, 3,777 patients were placed on emergency civil commitments (10) because they were considered dangerous to others, and another 890 patients were placed on extended involuntary hospitalizations (11) for the same reason; yet only 81 Tarasoff notifications were made. (Although not necessarily every patient who was committed as a danger to others had made a specific threat of violence against an identifiable victim, all were alleged to have represented an imminent risk of harm to others.)

To gain a more detailed understanding of the perpetrators and victims, we examined more closely the 229 notifications made in 1987, 1988, and 1989.

Origins of Notifications

Of the 229 notifications between 1987 and 1989, 65% (N=148) were made by nondoctoral mental health professionals (primarily social workers, nurses, and counselors), 26% (N=59) by psychiatrists, 1% (N=3) by psychologists, and 8% (N=19) by others. Fifty percent (N=114) of the reports originated from psychiatric hospitals, 22% (N=50) from crisis clinics, 10% (N=23) from halfway houses and outpatient clinics, 7% (N=17) from doctors' offices, and 11% (N=25) from other settings.

Characteristics of Patients Who Made Threats That Led to Notifications

Between 1987 and 1989, 83% (N=191) of the patients who made threats that led to notifications were male. Their mean age was 36.2 years (SD=10.8, range=17–85). Forty-nine percent (N=113) were white, 40% (N=92) were African American, 9% (N=20) were of other ethnic backgrounds, and 2% (N=4) were of unknown ethnicity.

Fifty-two percent (N=118) of the patients had records of arrests prior to the notifications: 31% (N=70) for violent crimes and 21% (N=49) for drug-related offenses. Fourteen percent (N=32) had records of arrests after the notifications, although the nature of the police record system did not permit determination of whether these arrests were specifically related to the threats leading to the notifications.

Characteristics of Victims of Threats

Although some patients threatened more than one person, for brevity of presentation we will describe the characteristics only of the person designated in the police record as primary victim of each threat. Between 1987 and 1989, 45% (N=104) of the targets of threats were female. (The gender of the victims was unknown in 14 cases.) Thirty-nine percent (N=90) were white, 17% (N=39) were African American, 14% (N=31) were of other ethnic backgrounds, and 30% (N=69) were of unknown ethnicity. Relationships of the targets to the perpetrators of the threats were as follows: 10% (N=24) were psychotherapists; 6% (N=13) were physicians; 14% (N=32) were spouses, boyfriends, or girlfriends; 8% (N=18) were former spouses, boyfriends, or girlfriends; 16% (N=36) were family members; 9% (N=20) were friends; 5% (N=11) were employers; 3% (N=8) were landlords; 3% (N=8) were famous people; 14% (N=31) were otherwise known to the threateners; and 12% (N=28) were of unspecified relationship.

Comparison of Public Sector Patients Who Did and Did Not Make Threats That Led to Notifications

To gain a general indication of how the demographic characteristics of patients who made threats that led to Tarasoff notifications compared with those of other patients, we selected the subset of patients for whom the notification was made from a public sector facility (e.g., psychiatric hospital, crisis clinic, or outpatient clinic). These patients were compared with all of the patients treated in the San Francisco community mental health system during the same time period who had not made threats that led to notifications. (This analysis did not consider whether or not either group of patients made threats that did not result in notifications.) The data presented earlier were given for calendar years (Jan. 1–Dec. 31). However, because the San Francisco community mental health system reports demographic data in units of fiscal years (July 1–June 30), the following comparisons consider data that were available for the fiscal years of 1986, 1987, and 1988. Use of fiscal years rather than calendar years yields somewhat different numbers of Tarasoff notifications from the numbers in the preceding presentation.

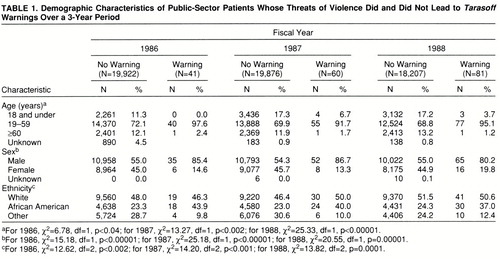

Table 1 shows that among public sector patients during fiscal years 1986, 1987, and 1988, those who made threats that led to Tarasoff warnings were significantly more likely than other patients to be between 19 and 59 years of age (relatively few were younger than 19 or older than 59) and were significantly more likely than the comparison group to be male. Patients who made threats that led to notifications were significantly more likely to be African American and less likely to be from other ethnic minority backgrounds. The proportion of white patients was similar among those who did and did not make threats that led to notifications.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study represents the first direct assessment of patterns of application of one of the duty-to-protect statutes in a large population. Our findings suggest that the mechanism recommended by the law to discharge that duty (i.e., both warning the victim of the threat and notifying the police) is rarely utilized. Previous research has consistently shown that a substantial proportion of people who are civilly committed on the basis of their dangerousness to others have recently made threats to harm others (12, 13). During the 5 years evaluated in the present study, several thousand civil commitments based on dangerousness to others were filed in San Francisco, but only 337 Tarasoff notifications were made. This pattern suggests that clinicians may have ignored the law or utilized other ways of protecting the targets of the threats besides the mechanism established by the law to demonstrate discharge of the duty. Several interventions besides warnings have been widely recommended (2, 14, 15) for managing the risk of violence in patients who make threats (e.g., involuntary hospitalization, which removes the opportunity for violence in the community). Additional options include intensified outpatient treatment (e.g., more frequent sessions), initiation or increase of psychotropic medication, removal of weapons from easy accessibility, and conjoint sessions involving the threatening patient and significant others, potentially including the target of the threat. Although these interventions appear reasonable, it is worth noting that in the original Tarasoff case, despite his attempts to effect involuntary hospitalization of the threatening patient, the therapist was held liable for failure to protect the victim after his patient had dropped out of treatment and carried out the threatened violence months later. In sum, while most therapists in our study appear to have used other methods to protect the victims of their patients' threats than the mechanism in the duty-to-protect statute, the liability to which they may have been exposed in the event of their patients' carrying out the threatened violence remains an issue that warrants consideration.

Our data show that only about half of the patients were hospitalized after the official notification of their threats. In contrast to what some experts have previously speculated about the redundancy between situations calling for Tarasoff notification and those requiring civil commitment (9), our findings suggest that clinicians were interpreting the standard for notification differently from the standard for involuntary hospitalization. We did not specifically evaluate the types of alternative dispositions that were implemented with the patients for whom Tarasoff reports were made. Previous research (16), however, suggests a variety of possibilities, such as arrest of the patient, an unsuccessful effort to have the patient hospitalized that was followed by a warning, diversion of the patient into substance abuse treatment, and the patient's dropping out of treatment and subsequent unavailability for other interventions.

A potential limitation of the generalizability of our findings is that clinical practices may have changed since the period covered by the study (1986–1990). The fact that the law has not changed and the observation that the number of warnings nevertheless remained low relative to the population of the community suggest some stability of our findings. Rates of notification increased over the first 3 years of implementation of the law, then leveled off in the fourth and fifth years. Even in the year with the highest number of reports (1990), the annual rate was 102 cases for a city of 750,000 residents (and a public sector mental health caseload of about 20,000), suggesting that the mechanism established by the law to discharge the duty to protect is rarely utilized. (Interestingly, Appelbaum [17], in reviewing surveys of clinicians from the 1950s to the 1990s, noted considerable consistency over time in the extent of clinicians' willingness to breach confidentiality to protect the potential victims of patients' violence, despite the controversial legal developments about the duty to protect that occurred over that interval.)

The fact that the majority of the notifications were made from public facilities such as psychiatric hospitals and crisis clinics suggests that fears about Tarasoff issues massively intruding on the confidentiality of private practice (18) have not materialized. Since hospitalization directly protects the victim of a patient's threatened violence by incapacitating the patient and providing treatment of mental disorders presumably affecting the risk of violence, one might wonder why half of the warnings came from hospitals. Apart from “defensive” practices geared to minimizing clinicians' exposure to liability, a variety of explanations is possible. Warnings to the victim of the threat have a clear clinical rationale when a patient escapes from a hospital, as providing this information alerts the target to the need for special safety precautions. Similarly, if the court releases a threatening patient over a clinician's objections, the clinician may perceive an ethical duty to make a warning. In addition, some patients show a diminution of acute symptoms (e.g., delusions about the target of violent threats) in the hospital but may have 1) a known history of noncompliance with community treatment (19), 2) a tendency to place themselves in situations that increase their violence potential (e.g., repeated substance abuse) (20), or 3) prominent personality traits associated with violence (e.g., psychopathy) (21). Although the clinician may have to discharge such patients when their acute symptoms decrease, knowledge of the patient's chronic potential for violence may affect a decision to make a warning from the hospital. It could be argued that over the long term, potential victims (e.g., the focuses of patients' delusions) may be in a better position to take actions to increase their own safety if they are aware that they are the targets of patients' threats. Finally, clinicians may notify the police after making reasonable, but unsuccessful, efforts to contact the victim because the police 1) have greater resources to locate the victim and 2) may also be able to determine if the threatening patient has had prior reports of threats or victims in other locales.

The finding that about half of the patients whose threats triggered Tarasoff warnings had histories of arrest suggests that this group had substantial involvement with criminal justice as well as mental health systems. The nature of the police record system precluded evaluation of whether the arrests that occurred after the notifications were directly related to the events that had originally led to the notifications. In any event, the finding that approximately one-sixth of the patients had records of arrest after the notifications is another indication that patients whose threats result in Tarasoff notifications have substantial involvement with the criminal justice system.

Our finding that almost half of the targets of patients' threats were family members, spouses, boyfriends, or girlfriends is consistent with results of past research showing that family members are the most common victims of violence by psychiatric patients (22). In addition, this finding supports the hypothesis of Wexler (23) that the Tarasoff type of situation may hold promise for family-oriented therapeutic interventions. Moreover, in a recent study that followed up on issues raised in the current study (24), we found that psychiatric residents who had made Tarasoff notifications said that these communications could often be managed so that the negative impact on the victims was minimal.

The observation that the patients who made threats that led to Tarasoff warnings tended to be men between the ages of 19 and 59 years is generally consistent with prior research showing associations of male gender (25) and younger age (26) with aggressive behavior in the community. Because we studied threats rather than physically violent actions, however, and because the age data for the comparison group were available only in general categories, these findings can be considered only tentative. The overrepresentation of African Americans and underrepresentation of other minority groups among the patients who made threats that resulted in Tarasoff notifications of authorities are intriguing. Because we did not have data on other variables that have been shown to moderate the relationship between ethnic background and aggressive behavior by mentally ill people (e.g., socioeconomic status, diagnosis) (25), our findings in this area are only suggestive. It is unclear whether this pattern could stem from 1) clinicians' overestimation of the risk posed by their African American patients (27), 2) more coexisting risk factors for aggression (e.g., low socioeconomic status) among public sector African American patients (20), 3) clinicians' greater willingness to use coercive interventions with African American patients (28), or 4) other possible explanations.

In conclusion, this study provides information about implementation of the first duty-to-protect statute, along with empirical data that can inform public policy when controversy arises about the impact of such legislation on clinical practice and the management of patients who make serious threats of violence.

|

Presented in part at the biennial conference of the American Psychology-Law Society/Division 41 of the American Psychological Association, Hilton Head, S.C., Feb. 29–March 2, 1996. Received June 4, 1997; revision received Dec. 1, 1997; accepted Feb. 9, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco; and the San Francisco Police Department. Address reprint requests to Dr. McNiel, Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute, 401 Parnassus Ave., San Francisco, CA 94143-0984.

1 Tarasoff v Regents of the University of California. 551 P 2d 334 (Cal 1976)Google Scholar

2 Beck JC (ed): Confidentiality Versus the Duty to Protect: Foreseeable Harm in the Practice of Psychiatry. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

3 Monahan J: The Clinical Prediction of Violent Behavior: DHHS Publication ADM 89-92. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1981Google Scholar

4 Appelbaum PS, Zonana H, Bonnie R, Roth LH: Statutory approaches to limiting psychiatrists' liability for their patients' violent acts. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:821–828Link, Google Scholar

5 California Civil Code, Section 43.92, 1985Google Scholar

6 Givelber DJ, Bowers WJ, Blitch CL: Tarasoff, myth, and reality: an empirical study of private law in action. Wisconsin Law Rev 1984:443–497Google Scholar

7 Wise TP: Where the public peril begins: a survey of psychotherapists to determine the effects of Tarasoff. Stanford Law Rev 1978; 135:165–190Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Jagim RD, Wittman WD, Noll JO: Mental health professionals' attitudes toward confidentiality, privilege, and third-party disclosure. Professional Psychol 1978; 9:458–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Gutheil TG: Legal issues in psychiatry, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 6th ed, vol 2. Edited by Kaplan HS, Sadock BA. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1995, pp 2747–2767Google Scholar

10 California Welfare and Institutions Code, Section 5150Google Scholar

11 California Welfare and Institutions Code, Section 5250Google Scholar

12 McNiel DE, Binder RL: Violence, civil commitment, and hospitalization. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:107–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 McNiel DE, Binder RL: Relationship between preadmission threats and later violent behavior by acute psychiatric inpatients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989; 40:605–608Abstract, Google Scholar

14 Monahan J: Limiting therapist exposure to Tarasoff liability: guidelines for risk containment. Am Psychol 1993; 48:242–250Crossref, Google Scholar

15 McNiel DE: Empirically based evaluation and management of the potentially violent patient, in Emergencies in Mental Health Practice: Evaluation and Management. Edited by Kleespies PM. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar

16 McNiel DE, Myers RS, Zeiner HK, Wolfe HS, Hatcher C: The role of violence in decisions about hospitalization from the psychiatric emergency room. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:207–212Link, Google Scholar

17 Appelbaum PS: Almost a Revolution: Mental Health Law and the Limits of Change. New York, Oxford University Press, 1994Google Scholar

18 Brief amicus curiae of American Psychiatric Association, et al, Tarasoff v Regents of the University of California, 551 P 2d 334 (Cal 1976)Google Scholar

19 Johnson DAW, Paterski G, Ludlow IM, Street K, Taylor RDW: The discontinuance of maintenance therapy in chronic schizophrenic patients: drug and social consequences. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67:339–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Swanson JW, Holzer CE, Ganju VK, Jono RT: Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:761–770Abstract, Google Scholar

21 Hare RD: Manual for the Hare Psychopathy Checklist—Revised. Toronto, Multi-Health Systems, 1991Google Scholar

22 Straznickas KA, McNiel DE, Binder RL: Violence toward family caregivers of the mentally ill. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:385–387Abstract, Google Scholar

23 Wexler DB: Therapeutic jurisprudence in clinical practice (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:453–455Link, Google Scholar

24 Binder RL, McNiel DE: Application of the Tarasoff ruling and its effect on the victim and the therapeutic relationship. Psychiatr Serv 1996; 47:1212–1215Link, Google Scholar

25 Binder RL, McNiel DE: The relationship between gender and violent behavior by acutely disturbed psychiatric patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51:110–114Medline, Google Scholar

26 Klassen D, O'Connor WA: Demographic and case history variables in risk assessment, in Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Edited by Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994, pp 229–257Google Scholar

27 McNiel DE, Binder RL: Correlates of accuracy in the assessment of psychiatric inpatients' risk of violence. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:901–906Link, Google Scholar

28 Lindsey KP, Paul GL: Involuntary commitments to public mental institutions: issues involving the overrepresentation of Blacks and assessment of relevant functioning. Psychol Bull 1989; 106:171–183Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar