Expenditures for the Treatment of Major Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Health policy makers lack accurate information about per capita spending for the treatment of major depression, the distribution of those expenditures, and the proportion of the health care dollar consumed by depression treatment. METHOD: The authors recruited and followed a community cohort of individuals with major depression; the 298 subjects were either enrolled in fee-for-service insurance plans or self-insured. Charges for all health care services received during the year following baseline were abstracted from medical and insurance records. RESULTS: Over the course of 1 year, 48.1% of the subjects received depression treatment. The per capita total expenditure for inpatient and outpatient depression treatment averaged $631, with a median of $152, for the treated subjects. Just 4.9% of the treated subjects consumed 45.0% of the outpatient expenditures. Depression treatment consumed only 8 cents of every health care dollar spent on the patients treated for depression. CONCLUSIONS: Studies are needed to examine how the level and distribution of expenditures for depression treatment change under managed care and to determine whether and how any differences affect outcomes in the afflicted population. Managed care attempts to contain costs by limiting outpatient care may not affect total health care expenditures dramatically, since depression treatment consumes such a minuscule portion of the health care dollar spent on this population. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:883–888)

Despite the substantial prevalence of major depression in the American population (1, 2), there is not enough information on treatment expenditures to evaluate the efficiency of the health care delivery system in treating the disorder. Findings from previous studies (1, 3) suggest considerable variation in the type and extent of treatment that patients get for depression; however, there is little generalizable information on how much treatment depressed patients receive, how much this treatment costs, and who pays for it. It is particularly important at this point in the evolution of the health delivery system to get a clear picture of the resources allocated to treat major depression in a fee-for-service system because these estimates can provide benchmarks with which to evaluate resource allocation in evolving managed care systems.

We addressed these questions by focusing on three objectives. The first objective of the study was to describe per capita expenditures in a fee-for-service system used to treat community-residing individuals with major depression. This line of investigation provides an important benchmark for future studies evaluating how much money managed care companies spend to treat patients for major depression. The second objective of this study was to characterize the distribution of expenditures on depression treatment by patient, provider, and payer characteristics. This line of investigation provides a second benchmark with which future studies can compare the ability of fee-for-service and managed care systems to allocate resources by clinical rather than nonclinical factors. The third objective of the study was to estimate the proportion of total health care expenditures spent by fee-for-service insurers on depression treatment for the afflicted population. This line of investigation provides a third benchmark for future studies concerned with whether managed care imposes greater cost controls on mental health services than it does on care for other problems.

Because few individuals receive inpatient depression treatment even in fee-for-service systems, we considered focusing exclusively on outpatient expenditures. While an exclusive outpatient focus eliminates the imprecision of expenditure estimates for inpatient care, comparisons of outpatient expenditures in fee-for-service and managed care systems are difficult to interpret because systems less likely to hospitalize severely depressed patients presumably provide them more intensive outpatient care during acute exacerbations. Estimates of outpatient treatment also grossly understate per capita spending for depression treatment because hospitalizations are a costly component of care. Thus, we elected to address our objectives by determining inpatient and outpatient expenditures separately and by developing models that predicted expenditure levels for outpatient expenditures only.

METHOD

Subject Recruitment and Data Collection

We conducted first-stage screening for current depression by using a 0.06 cutoff on the previously validated Burnam screener (4) during telephone interviews in 1992–1993 with randomly selected adults aged 18 years and over in 11,078 (70.5%) of 15,721 randomly selected Arkansas households with listed and unlisted telephone numbers. In order to address the aims of the original study, we used a stratified sampling design to oversample nonmetropolitan counties. Of the 11,078 screened household members, 998 (9.0%) screened positive for current depression. We excluded 286 bereaved, 54 manic, and 14 acutely suicidal subjects and eight individuals who denied all depressive symptoms at the baseline interview, and 470 (73.9%) of the 636 remaining depressed adults agreed to participate in a 3-hour, face-to-face baseline interview, which most subjects completed with~in 1 month after the telephone interview. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. The participants were similar to the nonparticipants in all socio~demographic and clinical characteristics (including depression severity) except age and residence. The participants were significantly younger—the mean ages of the participants and nonparticipants were 46.3 (SD=15.8) and 55.1 (SD=18.7) years (two-tailed t test: t=5.34, df=253, p<0.0001)—and more likely to reside in metropolitan areas (25.7% versus 16.9%) (χ2=5.39, df=1, p<0.02) than nonparticipants. Of the 470 subjects, 336 (71.5%) met the criteria for lifetime major depression with current symptoms during the baseline interview. We chose to eliminate subjects who screened positive without meeting the criteria for lifetime major depression because too few sought services to make reliable expenditure estimates.

Adapting previously validated questions from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (5), we conducted telephone interviews with 318 (94.6%) of the original 336 subjects 6 and 12 months after baseline to identify all hospitals, emergency rooms, outpatient care settings, and pharmacies that had provided professional health services for physical or emotional problems to each subject during the previous 6 months. With the subject's written permission after full explanation of the procedures, we requested complete medical and billing records from these providers. We reviewed these records in conjunction with the subject's insurance records in order to identify additional providers whom the subject had failed to recall. We contacted all providers repeatedly by writing, by telephone, or in person until complete medical and billing records were obtained. Using this method, we obtained complete billing records on 311 (97.8%) of the 318 subjects completing both the 6- and 12-month interviews. Records were determined to be complete when all relevant utilization and billing information was obtained from the subject's insurer and/or provider. Finally, we excluded 13 subjects in managed care health plans, leaving 298 subjects who are included in this analysis.

Abstraction of Records

To determine the charges associated with all health care utilization during the year following baseline, two research assistants abstracted expenditure data from records by following a detailed protocol under close faculty supervision. They achieved and sustained a high degree of reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.80). We elected to characterize billed rather than reimbursed expenditures because 1) physicians did not systematically record the proportion of expenditures they wrote off and 2) insurers agreed to provide information on charges but not reimbursements for 62 subjects.

Operational Definitions of Major Constructs

Using the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) for DSM-III-R (6) and the Inventory to Diagnose Depression (7), which were administered during the baseline interview, we categorized eligible subjects as having 1) major depression—defined as being at or above the cutpoint on the depression screen, a lifetime diagnosis of major depression on the DIS, and five or more symptoms in the last 2 weeks according to the Inventory to Diagnose Depression—or 2) subthreshold major depression—defined as being at or above the cutpoint on the depression screen, a lifetime diagnosis of major depression, and four or fewer symptoms in the last 2 weeks.

All expenditure estimates in this study and those reported from previous studies were expressed in 1994 dollars by using the medical care component of the consumer price index (8).

A hospitalization was defined as an admission to a health care facility that resulted in an overnight stay. A hospitalization was defined as depression treatment if 1) depression was coded as a diagnosis or noted as a symptom in the medical or billing record, 2) the subject received an antidepressant medication during the hospitalization, or 3) the subject noted the hospitalization was for depression.

An outpatient visit was defined as a visit to a medical doctor, osteopath, nurse practitioner, physician's assistant, or mental health professional in an office, clinic, or emergency room that did not result in an overnight stay. Outpatient visits were defined as depression treatment by using criteria parallel to those regarding hospitalization. Because psychotherapy delivered for other mental health diagnoses may potentially benefit co-occurring depression, we excluded a total of $3,384 for psychotherapy services delivered for diagnoses other than depression in this sample. We reasoned that the additional $24 per capita ($3,384/143) that this amount would add to our estimate of depression expenditures for the treated group would not materially change the major findings of this paper, and we elected to use the preceding definition to maintain consistency with previous publications (9).

The expenditures for outpatient depression treatment were categorized as provider services, prescriptions, or laboratory tests. Provider services included diagnosis, management (pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy), and monitoring. Prescription services included all antidepressant medications listed in recently released guidelines (10) and concomitantly prescribed minor tranquilizers. Laboratory tests included thyroid panel tests (except in cases where thyroid tests were administered to subjects with established thyroid diagnoses), reflecting the emphasis in published guidelines (11) on avoiding unnecessary tests to rule out other physical conditions before making the diagnosis of major depression.

For admissions, visits, or procedures involving multiple diagnoses, the psychiatrist raters used a detailed protocol to identify which expenditures were related to depression. This protocol is available from the authors on request.

The clinical predictors determined at baseline were major depression diagnosis (major depression, subthreshold major depression), dysthymia, psychiatric comorbidity, physical comorbidity, and previous psychiatric hospitalization. Depressive diagnosis and previous psychiatric hospitalization were determined by using the DIS (6). Psychiatric comorbidity was defined as the number of eight nonaffective lifetime psychiatric diagnoses present according to the Quick Diagnostic Interview Schedule (12). Physical comorbidity was the number of 12 chronic physical problems the subject reported. The nonclinical predictors determined at baseline were age, gender, race, education, income (ratio of the household income to the poverty line adjusted for family size), employment, marital status, residence in a nonmetropolitan statistical area, and health insurance (categorized from billing records as private, Medicare, Medicaid, or uninsured).

Outpatient visits were categorized as specialty care if the provider was a psychiatrist, psychologist, psychological examiner, social worker, or counselor. They were classified as general medical care if the provider was other than a mental health professional, such as an internist, family physician, or general practitioner.

Similar to the procedure in the National Medical Expenditure Survey (13), total health care expenditures were defined as all charges for inpatient hospital and physician services, outpatient physician and nonphysician services, and prescription medications. Optometry and dental charges were estimated in the National Medical Expenditure Survey, but that information was not collected in this study.

Data Analysis

To increase our subjects' representativeness of the depressed adults we identified in the telephone survey and to adjust for the stratified sampling design, we weighted the sample by age, gender, education, and regional distribution. We present our weighted Ns rounded to the nearest whole integer in the Results section. We report the results from descriptive statistics for depression treatment and overall health care expenditures. We used two-part regression models (14) to examine predictors of outpatient expenditures for depression. The first stage of the model estimated the probability of any use of outpatient services for depression by means of logistic regression. The second stage estimated the level of expenditures for depression for subjects who used any outpatient services for depression. Because of the skewed distribution of expenditures, we used the logarithm of the expenditure as the dependent variable in the second part of the model and relied on smearing retransformation to calculate predicted expenditure levels (15).

RESULTS

Subjects

The 11,078 subjects who completed telephone screen~ing were on average 51.4 years old (SD=18.3, range=18–99), 64.5% were female, 14.0% were minorities (predominantly African American), 75.5% had completed high school, 61.4% were married, 74.0% were residents of rural counties, and 85.8% had health insurance. The 298 subjects meeting the criteria for this analysis were on average 45.2 years old (SD=15.5, range=18–85), 67.7% were female, 16.8% were minorities (predominantly African American), 59.0% had completed high school, 59.6% were married, 65.6% were residents of rural counties, and 27.5% were self-insured. Diagnostic interviews indicated that 146 subjects met the criteria for major depression (59.5% with lifetime dysthymia) and 152 subjects met the criteria for subthreshold major depression (42.5% with lifetime dysthymia). The subjects reported an average of 2.6 (SD=2.0, range=0–9) chronic medical comorbid conditions apiece and 1.6 (SD=1.6, range=0–7) comorbid lifetime psychiatric diagnoses.

Depression Expenditures

For the 143 treated subjects, the total inpatient and outpatient per capita depression treatment expenditures averaged $631 (SD=$1,334, median=$152, range=$0–$9,389 [some received free treatment]). Their per capita expenditures for outpatient depression treatment averaged $492 (SD=$889, median=$149, range=$0–$6,204) for the 143 subjects who received outpatient depression treatment. Of the outpatient expenditures for the treated subjects, 73.2% were provided for provider services, 26.1% were for antidepressant medications and minor tranquilizers, and 0.7% were for laboratory tests. The providers of outpatient depression treatment charged private insurers for 38.7% of the expenditures, Medicare for 24.9%, the patients themselves for 27.2%, and Medicaid for 9.2%. Of the subjects receiving outpatient depression treatment, 75.9% visited a general medical physician only, 6.9% visited a mental health professional only, and 17.2% visited both a general medical physician and a mental health professional for depression treatment. The patients receiving any specialty care made an average of 11.7 specialty care visits for depression during the year, at an average charge of $151 per visit for depression treatment. The patients receiving any general medical care for depression made an average of 2.0 general medical visits for depression during the year, at an average charge of $113 per visit for depression treatment. It is possible that general medical providers monitored depressed patients more closely than the visit frequency suggests, as during the year subjects who received depression treatment in the general medical sector also made an average of 11.2 visits to general medical providers for physical problems only, at an average charge of $344 per visit.

Twelve subjects were hospitalized 14 times for depression during the year. Their per capita expenditures for inpatient depression treatment averaged $1,698 (SD=$2,989, median=$72, range=$15–$9,226). The $15 inpatient treatment expenditure reflects the psychiatrist raters' estimate of the cost of evaluating depression in a subject with multiple physical and emotional problems who received no specific treatment for depression.

Distribution and Predictors of Outpatient Depression Expenditures

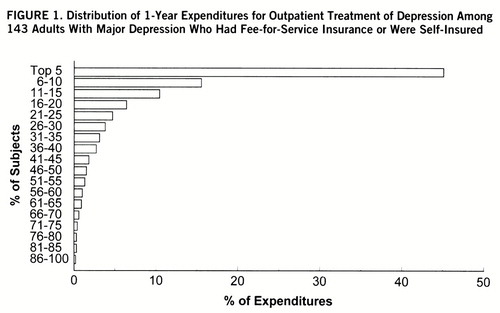

The distribution of outpatient expenditures among the 48.1% of subjects (143 of 298) receiving any outpatient depression treatment is shown in figure 1, illustrating that the top 4.9% of treated subjects accounted for 45.0% of all outpatient expenditures.

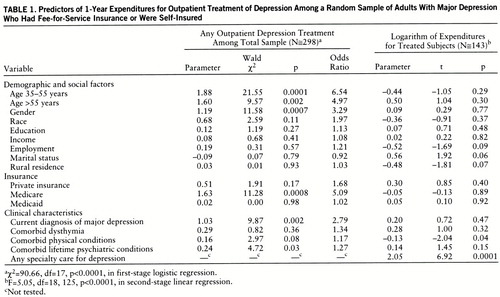

The first-stage logistic regression results are presented in table 1. Both clinical and nonclinical factors predicted outpatient treatment for depression. The significant clinical predictors were current major depression and lifetime psychiatric comorbidity. The nonclinical predictors were age 35–55 years old, age greater than 55, female gender, and Medicare coverage.

The second-stage regression results presented in table 1 indicate that among the patients who received any outpatient depression treatment, the predictors of greater expenditures for outpatient depression treatment were specialty care treatment, fewer comorbid physical conditions, currently being married, and urban residence. Compared to general medical care only, specialty care increased outpatient expenditures from $191 to $1,477 on average. Comorbid physical conditions decreased outpatient expenditures from $346 to $304 on average. Compared to not being married, being married increased outpatient expenditures from $256 to $448. Compared to rural residence, urban residence increased expenditures from $304 to $490 on average. Among the patients who received any outpatient depression treatment, clinical variables (current major depression, comorbid dysthymia, previous psychiatric hospitalization, comorbid physical conditions, and comorbid psychiatric conditions) explained 6.2% of the adjusted variance in expenditures in the second-stage equation. Clinical variables plus any specialty depression care explained 35.7% of the adjusted variance in the second-stage equation. Clinical variables plus specialty care treatment and nonclinical characteristics (age, gender, education, marital status, minority status, income, employment, insurance, and rural residence) explained 36.9% of the adjusted variance in the second-stage equation.

Depression Expenditures as Proportion of Total Health Care Expenditures

For the 298 subjects in the study, expenditures for inpatient and outpatient depression treatment (mean=$304, SD=$957, median=$0) averaged 5.6% of their total health care expenditures (mean=$5,381, SD=$10,870, median=$1,277). For the 143 subjects who received any depression treatment, expenditures for inpatient and outpatient depression treatment (mean=$631, SD=$1,334, median=$152) averaged 8.3% of total health care expenditures (mean=$7,586, SD=$12,289, median=$2,998). In comparison, inpatient and outpatient expenditures for mental health problems other than depression averaged 5.9% of the total health care expenditures for the entire 298 subjects and 5.5% of the health care expenditures for the 143 subjects treated for depression.

DISCUSSION

Our findings on the extent and distribution of spending for treatment of major depression in fee-for-service systems provide the following three benchmarks for future studies of expenditures under managed care systems.

Per Capita Depression Treatment Expenditures

Fee-for-service systems charged an average of $631 annually (1994 dollars) for every community-residing adult who sought treatment for major depression. If the 5.0% of American adults estimated to have an episode of major depression during the year used comparably priced services at the same rate as our sample, the country spent $2.7 billion for the treatment of major depression. Extrapolations from previously published findings derived from administrative databases have estimated that the country spends from $2.7 billion to $5.6 billion annually to treat major depression (16–18).

Health policy analysts need to know how much managed care systems spend per capita to treat major depression in adults who seek care for the problem, along with the outcomes they achieve, in order to evaluate performance. To compare managed care expenditures for major depression with the per capita expenditure levels we report, investigators will need to sample a comparable population rather than the selected and potentially healthier population of the individual health maintenance organizations (HMOs) studied to date (19–21), use comparable definitions for what constitutes depression treatment, and rectify the differences between charges and costs. If per capita spending is greater in fee-for-service systems than in managed care systems after adjustment for premium differences, investigations will be warranted to determine 1) whether managed care systems pocket the difference, spend it on other diagnoses, or expand access to the majority of depressed enrollees who fail to receive any care for the problem and 2) whether fee-for-service systems produce better outcomes than managed care systems, as the one study to address this question to date indicated (22).

Distribution of Depression Treatment Expenditures

While policy analysts may disagree about whether the United States spends sufficient resources on services for this serious and treatable disorder, there is probably more agreement that systems that provide care in a fee-for-service environment do not allocate available resources in a way that maximizes the benefit for those affected. One-half of afflicted adults receive no services at all, and 4.9% of those who use any services consume almost one-half the resources spent on outpatient treatment. The data indicate that social factors play a larger role in influencing whether individuals in fee-for-service systems get any outpatient depression treatment than in influencing the amount of treatment patients get once they enter outpatient care. Amount of treatment was predicted by 1) whether patients received any specialty care services (reflecting the higher cost of specialty care and the greater severity among specialty care patients on dimensions we were unable to measure in this study), 2) urban residence (reflecting the more intensive use of specialty care by urban patients), 3) current marital status (reflecting a potential positive impact of social support on extent of utilization), and 4) fewer comorbid physical conditions (reflecting probable monitoring of the course of depression by general medical providers during visits billed as care for physical problems only).

Depression Treatment Expenditures Relative to Total Health Care Expenditures

As managed care attempts to contain or reduce health care costs, it will be important to monitor how mental health's “slice of the pie” changes as the pie remains constant or shrinks. Fee-for-service systems spend 8 cents of every health care dollar to provide depression treatment for individuals with recognized major depression, and they spend another 6 cents to provide depressed patients with other mental health services. In comparison, the only study in an HMO setting published to date (19) indicated that 10 cents of every health care dollar pays for depression and other mental health services in a population with recognized depression. The small proportion of the depressed individual's total health care expenditures that is consumed by depression treatment suggests that managed care attempts to contain costs by limiting outpatient care may not affect total health care expenditures dramatically. The small proportion also suggests that evaluators need to track how efforts to improve the quality of depression treatment affect expenditures for physical comorbidity, as well as depression treatment.

Limitations

The study's conclusions are supported by our selection of a representative sample of depressed individuals rather than patients from a single system of care and by our use of prospective follow-up with multiple sources to record charges from actual billing records on over 90% of the cohort. This method, while expensive, has reduced the assumptions about treatment intensity and charge per treatment unit that other researchers have been forced to make in estimating treatment costs for major depression (16–18). However, the study's conclusions are limited in two important ways by features of the design. First, because we studied a random sample of individuals in a single state, the usefulness of this study's benchmarks depends on the representativeness of our sample in relation to depressed individuals across the country. While few indicators are available, it is encouraging that 45.0% of ECA subjects with major depression received any outpatient treatment in 1 year (1) given that 48.1% of the depressed individuals in our study received treatment. However, we know little about how the treatment intensity among those users compares to that of a national sample because no national estimates are available from studies that abstracted individual patient records. While we admit that these deficits make our estimates imperfect, the accelerated penetration of managed care makes it unlikely that the field will have a better estimate of fee-for-service spending for depression treatment from a more generalizable sample. Second, because our sampling strategy excluded individuals who were in institutions or without telephones, we lost a definable but costly portion of cases. The treatment of depression in institutionalized individuals is estimated to consume an additional $8.0 billion each year (17). Additional research to estimate depression treatment expenditures for individuals with very low incomes is clearly warranted so that public sector expenditures for the problem can be estimated more accurately.

Conclusions

In summary, these descriptive data estimating treatment costs for a representative group of depressed individuals served by fee-for-service systems provide critical baseline data for making informed judgments about the multiple efforts currently underway to restructure the delivery of mental health services to provide more cost-effective treatment to more individuals in need. After system-wide changes are implemented, parallel studies are needed to evaluate how the reorganization has affected use, outcomes, and expenditures for depression care provided to individuals with major depression.

|

Presented in part at the NIMH International Conference on Mental Health Services Research, Washington, D.C., Sept. 11–12, 1995. Received Jan. 21, 1997; revisions received July 23, Oct. 8, and Nov. 18, 1997; accepted Dec. 22, 1997. From the VA Health Services Research and Development Field Program for Mental Health, VA Medical Center, Little Rock, Ark., and the Center for Rural Mental Healthcare Research and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Address reprint requests to Dr. Rost, Center for Rural Mental Healthcare Research, Suite 605, 5800 West 10th St., Little Rock, AR 72204; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-49116, MH-48197, MH-55297, and MH-54444. The authors thank Linda Deloney, Carl Elliott, Stacy Kimbrel, Madonna Gautreau, Debbie Hodges, Dan Hoyt, Marki Kimball, Phyllis Linkswiler, Cindy Mosley, Cynthia Moton, Rick Owen, Robin Ross, Blair Tompkins, Ryan Turk, and Charlotte Williams.

FIGURE 1. Distribution of 1-Year Expenditures for Outpatient Treatment of Depression Among 143 Adults With Major Depression Who Had Fee-for-Service Insurance or Were Self-Insured

1 Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:85–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Hu TW, Rush AJ: Depressive disorders: treatment patterns and costs of treatment in the private sector of the United States. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1995; 30:224–230Medline, Google Scholar

4 Burnam MA, Wells KB, Leake B, Landsverk J: Development of a brief screening instrument for detecting depressive disorders. Med Care 1988; 26:775–789Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Shapiro S, Tischler GL, Cottler L, George L, Amirkhan J, Kessler L, Skinner E: Health services research questions, in Epidemiologic Field Methods in Psychiatry: The NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Edited by Eaton WW, Kessler LG. Orlando, Fla, Academic Press, 1985, pp 191–208Google Scholar

6 Robins LN, Helzer JE, Cottler L, Golding E: National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version III, revised. St Louis, Washington University, Department of Psychiatry, 1989Google Scholar

7 Zimmerman M, Coryell W: The Inventory to Diagnose Depression (IDD): a self-report scale to diagnose major depressive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1987; 55:55–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 US Bureau of the Census: Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1994. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1994Google Scholar

9 Fortney JC, Rost K, Zhang M: A joint choice model of the decision to seek depression treatment and choice of provider sector. Med Care 1998; 36:307–320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Depression Guideline Panel: Depression in Primary Care, vol 2: Treatment of Major Depression: Clinical Practice Guideline 5: AHCPR Publication 93-0551. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

11 Depression Guideline Panel: Depression in Primary Care, vol 1: Detection and Diagnosis: Clinical Practice Guideline 5: AHCPR Publication 93-0550. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

12 Marcus S, Robins LN, Bucholz K: Quick Diagnostic Interview Schedule III-R: Version 1.0. St Louis, Washington University School of Medicine, 1991Google Scholar

13 Hahn B, Lefkowitz D: National Medical Expenditure Survey: Annual Expenses and Sources of Payment for Health Care Services: Research Findings 14. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1992Google Scholar

14 Duan N, Manning WG Jr, Morris CN, Newhouse JP: Choosing between the sample-selection model and the multi-part model. J Business and Economic Statistics 1984; 2:283–289Google Scholar

15 Duan N: Smearing estimate: a nonparametric retransformation method. J Am Statistical Assoc 1983; 78:605–610Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER: The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:405–418Medline, Google Scholar

17 Rice DP, Miller LS: The economic burden of affective disorders. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Res 1993; 14:21–37Google Scholar

18 Stoudemire A, Frank R, Hedemark N, Kamlet M, Blazer D: The economic burden of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1986; 8:387–394Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W: Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:850–856Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W: Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:352–357Link, Google Scholar

21 Sclar DA, Robison LM, Skaer TL, Legg RF, Nemec NL, Galin RS, Hughes TE, Buesching DP: Antidepressant pharmaco~therapy: economic outcomes in a health maintenance organization. Clin Ther 1994; 16:715–730Medline, Google Scholar

22 Rogers WH, Wells KB, Meredith LS, Sturm R, Burnam MA: Out~comes for adult outpatients with depression under prepaid or fee-for-service financing. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:517–525Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar