Changes in Guideline-Recommended Medication Possession After Implementing Kendra's Law in New York

Involuntary outpatient commitment laws are intended to ensure that persons with severe and persistent mental illness adhere to recommended treatment in the community, with the goal of averting relapse, repeated hospitalizations, and violent behavior ( 1 ). However, these laws are also controversial, with critics asserting that they are coercive and would be unnecessary if adequate treatment and resources in the community were available for persons with severe mental illness ( 2 , 3 ). Many states have implemented such laws, but evidence for their efficacy and effectiveness from prior randomized and naturalistic studies has been inconclusive ( 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). In 1999 New York State enacted Kendra's Law, which provides for the state's court-ordered involuntary outpatient commitment program, termed assisted outpatient treatment (AOT). Recent evidence shows that the program was associated with decreased hospitalization and improved service engagement and medication adherence ( 8 , 9 ).

While evidence accumulates regarding the effectiveness of involuntary outpatient commitment, it is worth examining whether there are spillover effects on quality or outcomes for other persons with severe mental illnesses who are treated in the system but do not receive this intervention. In New York State, persons with a court order for AOT also receive priority for resources such as housing and enhanced outpatient services. There is evidence that, at least initially, the increased attention and resources given to these patients were associated with decreased use of services by other, equally needy patients without court orders ( 10 ). Furthermore, there are regional differences in the ability to absorb the increased service and resource demands ( 10 , 11 ). No prior research has examined whether, after implementing outpatient commitment, there are changes in treatment quality or outcomes for persons who are severely ill but not receiving mandatory or intensive services or whether there are regional differences in these trends.

In this study we used Medicaid claims data to examine changes in the medication possession ratio (MPR) of guideline-recommended medications for patients who had severe mental illness but differed as to whether they received AOT, enhanced services, or neither. We also examined whether these changes varied by region. Because the MPR of guideline-recommended pharmacotherapy is determined not only by patient characteristics but also by the quality and availability of treatment resources in a community, and because there is an established link between MPR from administrative data for prescription fill rates and improved treatment outcomes ( 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ), we used the MPR as a single proxy for treatment availability, quality, and outcome.

Methods

This project was approved by the institutional review boards of Duke University, Policy Research Associates, New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH), and Biomedical Research Alliance of New York.

Data source and population

OMH provided Medicaid administrative data that included inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy claims from January 1, 1999, through March 14, 2007. The data set included claims from three enrollee groups: all recipients of AOT, those who received enhanced voluntary services but never received AOT, and those who never received either intervention. AOT status was determined by the state's Tracking for Assistant Outpatient Treatment Cases and Treatments database, and this information was merged with the Medicaid claims.

New York State provides two forms of enhanced services: assertive community treatment (ACT) and intensive case management. The latter is similar to ACT in many ways (such as high staff-to-patient ratios, intensive patient outreach, 24-hour coverage, and frequent patient contact in the community). Unlike ACT teams, however, intensive case management teams typically do not share caseloads ( 10 ). In this analysis, we combined ACT and intensive case management data and refer to them collectively as enhanced services.

The state provided the voluntary enhanced services sample according to the following selection criteria: current service user with a record of receiving outpatient mental health services on or after July 1, 2006; at least one psychiatric inpatient hospitalization since 1999 with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depression with psychotic features; two or more psychiatric inpatient admissions in any year since 1999; a total of 14 or more inpatient days in any single year; and use of voluntary enhanced services at any time since 1999. The diagnostic and hospitalization criteria were selected to approximate AOT referral criteria that are observable in claims data. Criteria for the "neither intervention" sample were the same as for the voluntary enhanced services sample, except that participants had not received enhanced services. Given these criteria, we would expect persons in the "neither" group to have more severe illness profiles than a typical Medicaid-served usual care population.

We limited our study sample to enrollees in New York City, on Long Island, and in the Hudson River, the three largest regions with AOT orders (representing 95% of New York's orders) ( 17 ) because the sample size in other regions would be too small for comparisons. We also limited our sample to enrollees with diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder, which represented 93% of the study population in the data provided by the state. We did so for several reasons. First, claims data have demonstrated reliability for developing diagnostic cohorts in these populations (Geiger-Brown J., Steinwachs D., Fahey M., et al., personal communication with A. F. Lehman, July 17, 2002; 18–20). Second, our primary outcome was guideline-recommended medication possession, and expert guidelines recommend chronic, maintenance pharmacotherapy as an important component of treatment for all persons with these illnesses ( 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ). Claims through year 2006 were used to identify the enrollee treatment and intervention group, but medication utilization claims were used only through 2005 because of Medicare Part D implementation on January 1, 2006, after which Medicaid enrollees dually eligible for Medicare no longer had their pharmacy claims paid by Medicaid.

Outcome variable

The MPR was calculated with the dates that prescriptions were filled to determine the proportion of each month that the recipient would have possessed a supply of medication. The MPR was calculated only for medications recommended by expert guidelines or as indicated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of the patient's primary psychiatric disorder, as diagnosed by a psychiatrist during an inpatient stay or an outpatient or emergency department visit. For example, for patients with bipolar disorder, the MPR was calculated on the basis of mood stabilizer (lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine) or antipsychotic prescriptions. We limited the diagnoses to those determined by psychiatrists because they would be prescribing the psychiatric medications from which the MPR was determined. The MPR was dichotomized at 80% or greater because prior studies have found it (or similar measures) to be associated with decreased hospitalization in severely mentally ill populations ( 12 , 14 , 27 , 28 ).

Explanatory variables

Explanatory variables included the patient characteristics of age (continuous variable), gender, race-ethnicity (black, white, Hispanic, or other), and Medicaid eligibility category (Supplemental Security Income, dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid, and other). Clinical variables included psychiatric diagnosis (specifically, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder) and psychiatric hospitalization in a given month. We measured time in months.

New York's AOT program requires participants to receive enhanced services; as a result, the state increased annual appropriations at the start of the program, in 1999, to increase capacity for these services. Despite these changes, the availability of enhanced services initially was limited to those in the AOT program ( 10 ). Therefore, enrollees who received AOT or enhanced services in earlier years may have differed in unobservable characteristics (such as illness severity, insight into illness, or ability to adhere to treatment) from those who received these interventions in subsequent years—which could be associated with differences in MPR. To address this, we identified year of the first observed AOT order for those in the AOT group, the first observed enhanced services claim in the voluntary enhanced services group, or the first Medicaid mental health treatment claim for any treatment in the "neither" group and included these as controls in our models. Long Island and the Hudson River had very few AOT orders in 1999; therefore, we dropped year 1999 claims from the analysis and began with year 2000.

Because active enrollment in AOT or enhanced services could bias the MPR (for example, ACT and intensive case management clinical staff may pick up prescriptions for patients, but patients still may not adhere to the medication regimen), we controlled for the use of AOT or enhanced services in a given month. However, we did not control for duration of current or prior exposure to AOT or enhanced services because these characteristics would vary according to the resources and capacity of a treatment system.

Statistical methods

We fit nine logistic regression models, one for each region (New York City, Long Island, and the Hudson River) and treatment group (AOT, voluntary enhanced services, and neither) combination. The unit of analysis was the person-month. The models were identical in terms of the demographic, clinical, and first-observed-treatment variables described above. In addition, models for the AOT group included the variables for current month being on AOT, enhanced services, or both, and models for the voluntary enhanced services group included the variable for current month being on enhanced services. We used a generalized estimating equations approach to account for multiple observations per person ( 29 ). Predicted probabilities of MPR ≥80% for each month were calculated from the logistic regression results.

Although having a comorbid substance use disorder is associated with medication nonadherence ( 13 , 15 , 30 ), we did not control for this in the models because it was underrecorded in the claims data. Only 7% of the AOT sample had a substance use disorder diagnosis in the claims, whereas a separate data collection instrument completed by AOT case managers (the Child and Adult Integrated Reporting System) indicated that comorbid substance use disorders were reported for approximately 50% of AOT recipients. As a sensitivity analysis, we included a dichotomous variable for substance use disorders in the models for the AOT and enhanced services groups to examine whether including this information from the claims altered the results.

With the claims data set supplied by the state, only enrollees in the AOT group were not required to have a treatment claim in 2006 to be included in the study sample. Therefore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we excluded the AOT recipients who did not receive any services in 2006 (18.9% of the recipients). We also conducted sensitivity analyses controlling for the proportion of a calendar year (number of months as a continuous variable) that individuals were enrolled in Medicaid.

Results

Consistent with the distribution of statewide AOT orders, most of our study sample was from New York City (81%) ( Table 1 ). For approximately half of the study sample, the first observed Medicaid treatment claim was in the year 2000. There were regional differences in race and ethnicity, with New York City having a lower percentage of non-Hispanic whites. Long Island enrollees were more likely to have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (16% versus 11% in New York City and 11% in the Hudson River).

|

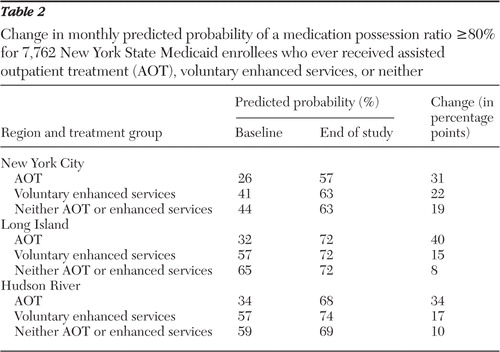

Across all three regions, enrollees in the AOT group had lower baseline probabilities that the MPR would be 80% or higher compared with those in the voluntary enhanced services and "neither" groups ( Table 2 ). Enrollees in all three groups and in each region had an increased probability of MPR ≥80% over time. Also in all three regions, the AOT group experienced the greatest improvement over time.

|

Regional differences in the MPR trajectories at study endpoint were observed ( Table 2 ; in addition, a figure is available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org ). In New York City, the voluntary enhanced services and "neither" groups had similar endpoint probabilities that MPR would be 80% or higher. In Long Island, all three groups had the same endpoint MPR probability. In the Hudson River, the endpoint MPR probability was highest in the voluntary enhanced services group and lower for the other two. [Results of the logistic regression models are available in an online supplemental appendix to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

These results were robust to all three sensitivity analyses; that is, including substance use disorder in the models, controlling for the proportion of the calendar year in which patients were enrolled, and dropping from the analysis the AOT recipients who did not use Medicaid services in 2006 all yielded similar model results.

Discussion

The predicted probability of MPR ≥80% improved for all three treatment groups in each region. Although the absence of a counterfactual comparison group makes it difficult to know what the MPR outcomes would have been without these interventions in New York State, it is at least reassuring that we did not observe any apparent medication possession declines for patient groups who did not receive AOT but who were nonetheless severely ill.

We found some regional differences in the MPR trends. For example, by study's end in New York City and Long Island, the "neither" groups fared similarly in the MPR outcome compared with the voluntary enhanced services groups, whereas in the Hudson River the outcome of the "neither" group fell below that of the enhanced services group. Additional study is needed to better understand these regional trends and what they represent in terms of treatment experience or quality to enrollees.

When comparing among treatment groups within a region, it is important to remember that the groups are not fully equivalent. Although we controlled for observable patient and treatment characteristics, there were unobservable patient characteristics that influenced whether someone received AOT, enhanced services, or neither. Therefore, we would not expect MPR trajectories to be equivalent among groups. Despite this challenge, examining whether the trends differed by region is important in understanding whether the introduction of AOT and additional resources into the system was associated with guideline-recommended MPR gains across the system for severely ill, vulnerable patient populations.

We found higher increases in medication fill rates than found in previous longitudinal studies of other severely mentally ill populations ( 15 , 31 , 32 ). In addition to the differing populations and methodologies in these earlier studies, differences among treatment groups in our study also may account for some of this variance. For the AOT group (the group with the greatest MPR improvement) we examined whether changes in issuing 30-day versus 90-day prescriptions could contribute to this finding but found proportions of 30- and 90-day prescriptions unchanged during the study period. In the AOT groups, the steep rise in MPR ≥80% may have occurred because enrollees went from nearly 0% exposure to AOT to 100% by study's end. Although everyone in the voluntary enhanced services groups would be exposed to that intervention by the end of the study period, it is likely that at least some had been exposed to enhanced services before 2000 and that the "neither" group had no intensive services history. Given the recent evidence that New York's AOT program was associated with improved MPR outcomes and that improvements could be seen after the court order was discontinued ( 9 , 33 ), we would expect to see significant increases in MPR for patients who received AOT. Finally, in both the enhanced services and "neither" groups, the samples were derived from persons currently enrolled in Medicaid in 2006—and enrollees present in earlier years (but not 2006) were not included in the samples. Therefore, some selection bias may have been introduced, with our study sample's possibly being older or more clinically stable (either at baseline or because of optimized treatment from longer treatment retention) than enrollees who were previously but not currently enrolled as of 2006.

The different regional trends might have occurred in the absence of AOT implementation in New York State, but it is also possible that the different trajectories were due to regional differences in implementation or other regional characteristics. Given that the mean probability of MPR ≥80% was lower at baseline in New York City than in the Hudson River and Long Island regions, it is clear that regions differed in the baseline MPR that was associated with receiving an AOT order. Other regional differences in New York State could have affected these regional trends, such as differences in service system capacity or AOT implementation policies, which are documented in this issue's special section ( 11 ). Future study is needed to better understand the relationship between regional service system characteristics, AOT implementation, and treatment outcomes for patients with severe mental illness across these groups.

There are several important limitations to these data. Although claims data have demonstrated reliability and accuracy in developing diagnostic cohorts, specifically for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (Geiger-Brown J., Steinwachs D., Fahey M., et al., personal communication with A. F. Lehman, July 17, 2002; 18–20), they tend to underdetect substance use disorder comorbidity ( 34 , 35 ), as was observed in our data. However, including substance use disorder in the models did not appreciably alter the results. Given the literature describing increased rates of nonadherence for patients with a comorbid substance use disorder ( 27 , 36 , 37 ), the undercoding of this comorbidity in the claims may have led to a false null result in the sensitivity analyses because the proportion of enrollees with a false-negative result was sufficiently large and biased the sensitivity results. Second, the MPR represents prescription fill rates, not adherence specifically. Patients may fill a prescription but not take the medication. This could be a particular issue for enrollees receiving enhanced services, where mental health clinicians are more likely to fill prescriptions for their patients. We controlled for receipt of enhanced services in a given month to mitigate this effect. Patients may receive medications through sources other than Medicaid (which would underestimate MPR). Although these potential sources of bias in MPR would affect the point estimates, they would be less likely to affect the relative regional differences in the MPR trajectories across groups.

Conclusions

This is the first study examining regional changes in guideline-recommended medication possession among severely mentally ill Medicaid enrollees—including those not receiving intensive outpatient services—after the state's implementation of outpatient commitment. Improvements in MPR were seen in all three regions and across all treatment groups. Despite different methodologies, our results are consistent with other research in this issue of Psychiatric Services demonstrating that AOT was associated with improved MPR ( 9 , 33 ). However, differences in the MPR trends also emphasize the need for policy makers to monitor changes in treatment quality regionally and among enrollees with varied treatment intensity needs who are served in the public mental health system. Further study is needed to understand why there were different regional trajectories and why some groups did not gain similarly across regions.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The study was funded by grant K01MH071714 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Busch and by the New York State Office of Mental Health, with additional support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of numerous individuals in collecting, synthesizing, and reporting the data for this effort. At the Services Effectiveness Research Program, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, the authors acknowledge the considerable efforts of Lorna L. Moser, Ph.D., and Allison R Gilbert Ph.D, M.P.H. At Policy Research Associates, they thank Pamela Clark Robbins, Henry J. Steadman, Ph.D., Karli J. Keator, B.A., Wendy Vogel, M.P.A., Roumen Vesselinov, Ph.D., Jody Zabel, Steven Hornsby, L.M.S.W., and Amy Thompson, M.S.W. They also acknowledge the extensive reviews and critical feedback provided by the MacArthur Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment, which served as an internal advisory group to the study. Although the findings of the study are solely the responsibility of the authors, they gratefully acknowledge the support and assistance of the New York State Office of Mental Health in completing the report, including Steve Huz, Ph.D., Chip Felton, M.S.W., Peter Lannon, Susan Shilling, J.D., L.C.S.W., Qingxian Chen, Michael F. Hogan, Ph.D., Bruce E. Feig, and Lloyd I. Sederer, M.D.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Swartz MS, Monahan J: Special section on involuntary outpatient commitment: introduction. Psychiatric Services 52:323–324, 2001Google Scholar

2. Monahan J, Swartz M, Bonnie RJ: Mandated treatment in the community for people with mental disorders. Health Affairs 22(5):28–38, 2003Google Scholar

3. Committee for Persons in Recovery: US Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association Position Paper on Involuntary Outpatient Commitment. Linthicum, Md, US Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association, 2007Google Scholar

4. Keilitz I: Empirical studies of involuntary outpatient civil commitment: is it working? Mental and Physical Disability Law Reporter 14:368–379, 1990Google Scholar

5. Swartz M, Swanson J, Hiday V, et al: A randomized controlled trial of outpatient commitment in North Carolina. Psychiatric Services 52:325–329, 2001Google Scholar

6. Steadman H, Gounis K, Dennis D, et al: Assessing the New York City involuntary outpatient commitment pilot program. Psychiatric Services 52:330–336, 2001Google Scholar

7. Swartz MS, Burns BJ, Hiday VA, et al: New directions in research on involuntary outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 46:381–385, 1995Google Scholar

8. Gilbert AR, Moser LL, Van Dorn RA, et al: Reductions in arrest under assisted outpatient treatment in New York. Psychiatric Services 61:996–999, 2010Google Scholar

9. Van Dorn RA, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al: Continuing medication and hospitalization outcomes after assisted outpatient treatment in New York. Psychiatric Services 61:982–987, 2010Google Scholar

10. Swanson JW, Van Dorn RA, Swartz MS, et al: Robbing Peter to pay Paul: did New York State's outpatient commitment program crowd out voluntary service recipients? Psychiatric Services 61:988–995, 2010Google Scholar

11. Robbins PC, Keator KJ, Steadman HJ, et al: Regional differences in New York's assisted outpatient treatment program. Psychiatric Services 61:970–975, 2010Google Scholar

12. Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al: Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:692–699, 2004Google Scholar

13. Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow F, et al: Treatment adherence with lithium and anticonvulsant medications among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 58:855–863, 2007Google Scholar

14. Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al: Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Medical Care 40:630–639, 2002Google Scholar

15. Valenstein M, Ganoczy D, McCarthy JF, et al: Antipsychotic adherence over time among patients receiving treatment for schizophrenia: a retrospective review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:1452–1550, 2006Google Scholar

16. Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al: Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 55:886–891, 2004Google Scholar

17. Recipients Under Court Order, by Region. New York, New York State Office of Mental Health, 2007. Available at http://bi.omh.state.ny.us/aot/statistics?p=under-court-order Google Scholar

18. Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, et al: Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:69–71, 1992Google Scholar

19. Unützer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, et al: The treated prevalence of bipolar disorder in a large staff-model HMO. Psychiatric Services 49:1072–1078, 1998Google Scholar

20. Unützer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, et al: The use of administrative data to assess quality of care for bipolar disorder in a large staff model HMO. General Hospital Psychiatry 22:1–10, 2000Google Scholar

21. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). American Journal of Psychiatry 159(Apr suppl):1–50, 2002Google Scholar

22. Bauer MS, Callahan AM, Jampala C, et al: Clinical practice guidelines for bipolar disorder from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:9–21, 1999Google Scholar

23. Keck PE Jr, Perlis RH, Otto MW, et al: Expert Consensus Series: Treatment of bipolar disorder 2004. Postgraduate Medicine Special Report December:1–120, 2004Google Scholar

24. Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, et al: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:193–217, 2004Google Scholar

25. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1–10, 1998Google Scholar

26. Suppes T, Dennehy EB, Hirschfeld RMA, et al: The Texas implementation of medication algorithms: update to the algorithms for treatment of bipolar I disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:870–886, 2005Google Scholar

27. Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow FC, et al: Treatment adherence with antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 8:232–241, 2006Google Scholar

28. Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney J: Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatric Services 52:805–811, 2001Google Scholar

29. Zeger SL, Liang KY: Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 42:121–130, 1986Google Scholar

30. Manwani SG, Szilagyi KA, Zablotsky B, et al: Adherence to pharmacotherapy in bipolar disorder patients with and without co-occurring substance use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68:1172–1176, 2007Google Scholar

31. Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Neelon B, et al: Longitudinal racial/ethnic disparities in antimanic medication use in bipolar-I disorder. Medical Care 47:1217–1228, 2009Google Scholar

32. Busch AB, Lehman AF, Goldman HH, et al: Changes over time and disparities in schizophrenia treatment quality. Medical Care 44:199–208, 2009Google Scholar

33. Swartz MS, Wilder CM, Swanson JW, et al: Assessing outcomes for consumers in New York's assisted outpatient treatment program. Psychiatric Services 61:976–981, 2010Google Scholar

34. Farris C, Brems C, Johnson ME, et al: A comparison of schizophrenic patients with or without coexisting substance use disorder. Psychiatric Quarterly 74:205–222, 2003Google Scholar

35. Kirchner JE, Owen RR, Nordquist C, et al: Diagnosis and management of substance use disorders among inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 49:82–85, 1998Google Scholar

36. Drake RE, Osher FC, Wallach MA: Alcohol use and abuse in schizophrenia: a prospective community study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:408–414, 1989Google Scholar

37. Swofford CD, Scheller-Gilkey G, Miller AH, et al: Double jeopardy: schizophrenia and substance use. American Journal on Drug and Alcohol Abuse 26:343–353, 2000Google Scholar