Use of Psychoactive Substances and Health Care in Response to Anxiety and Depressive Disorders

According to large national and international surveys, psychiatric disorders occur frequently in the general population ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). In response to the discomfort caused by these disorders, relatively few people use specialty mental health care, defined as care rendered by individuals trained to assess, refer, and treat persons with mental or emotional problems. In a review, Kohn and colleagues ( 10 ) calculated that more than 50% of mental health needs remain unmet. However, there are several other types of responses to psychological distress ( 11 ). As posited by the self-medication hypothesis and the alleviation of dysphoria model ( 12 , 13 , 14 ), psychoactive substance use is one of these responses and has been described in different populations ( 15 , 16 , 17 ). Bolton and colleagues ( 18 ) described substance use in response to lifetime anxiety disorders using the data of the 1990–1992 National Comorbidity Survey and found that frequencies of this type of substance use ranged from 7.9% (social phobia, speaking subtype) to 35.6% (generalized anxiety). However, frequencies were not estimated separately by gender, even though gender is known to be linked to substance use and to mental disorders ( 9 , 19 ). Moreover, mental health care use has not been studied jointly with substance use as responses to psychiatric disorders. Patients with psychiatric disorders who use health care are likely to be relieved from their psychological symptoms, so that their need to use psychoactive substances should be lower compared with persons not using health care. Previous studies showed that mental health service use was associated with lower rates of substance use disorders among persons with two or more psychiatric disorders ( 20 , 21 ).

The objectives of the study presented here were to estimate by gender the frequencies of use of psychoactive substances and of health care in response to anxiety or depressive disorders and to determine factors associated with these behaviors. Data for this study were gathered with a large population-based survey.

Methods

Study design and setting

We used data from a cross-sectional survey designed to assess mental health indicators in France. Four regions of France volunteered to participate in this survey: Ile de France, Haute-Normandie, Lorraine, and Rhone Alpes. In each region, participants were selected with a two-stage procedure. First, households were randomly selected, and then one adult per household was randomly selected according to a method proposed by Kish ( 22 ). Sampling was based on a file of listed numbers obtained for each region from the telephone directory. A new list was obtained by replacement of the last digit by a randomly chosen one. Thus it contained listed and unlisted numbers. Exclusion criteria for households were not living in one of the four regions, not answering after 15 calls, not being a French speaker, and declining to participate in the survey.

Exclusion criteria for participants were being younger than 18 years, not answering after 15 calls, being a non-French speaker, being unable to answer the phone or complete the interview (could not hear the questions, did not answer the questions or answered inconsistently, was under the influence of alcohol or other psychoactive substances, or had a physical illness that prevented him or her from talking for a long time), and declining to participate in the survey.

Sample

For the study presented here, only participants with a probable 12-month anxiety or depressive disorder were selected. Those with a 12-month substance use disorder were excluded.

The study protocol was approved by the French regulation authority for questionnaire-based noninvasive medical research (Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés). Participants were given a complete description of the study and were asked to provide informed consent.

Data collection

Data were collected by phone from April to June 2005 by trained interviewers who used computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI). CATI employs interactive computing systems to assist interviewers and their supervisors in performing the basic collection tasks of telephone surveys.

Sociodemographic variables. Sociodemographic variables were gender, age, marital status, education level, housing ownership, and country of birth.

Anxiety and depressive disorders. DSM-IV ( 23 ) axis I disorders were assessed with the short form of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-SF) ( 24 ). This instrument made it possible to assess the probability of the presence of the following disorders: major depressive episode, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic attack, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and alcohol or drug use disorders (abuse and dependence). This version was adapted from the French version of the CIDI used in the European Survey of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) ( 25 ). In this study, only probabilities of having a 12-month disorder were calculated.

Disability. Disability was assessed by the Sheehan Disability Scale for each disorder separately ( 26 ). This scale allows the evaluation of disability by using four questions dealing with work, home life, social life, and family life. The answer to each question is coded from 0, no disability, to 10, severe disability; a score of 7 or above is considered to represent a significant impairment. Because all four questions did not necessarily apply to every participant, we computed an average score over the questions that were applicable. Participants were then considered as disabled by their condition if their average score was 7 or above.

Responses to anxiety and depressive disorders. In the course of the interview, each disorder corresponded to a section of the questionnaire. After questions about the disorder's symptoms, questions were asked concerning the participant's responses to these specific symptoms: consulting a medical doctor (general practitioner, psychiatrist, or other medical specialist specified), consulting a nonmedical mental health provider (psychologist or psychotherapist), consulting another professional (social worker or nurse), or using psychoactive substances (alcohol or illicit drugs). These questions were asked separately for each anxiety or depressive disorder. Therefore, it was possible to determine the presence or absence of these responses for each anxiety or depressive disorder.

Consultation with a social worker, a nurse, or another professional was not categorized as health care use in this study, because in France they are not mental health professionals.

Perceived social support. Social support was documented with four questions ( 27 ): Do you have a close friend or family member with whom you can easily talk about your problems? Do you know someone you can count on in case of crisis? Do you know someone you can count on when you have important decisions to make? Do you have someone who makes you feel loved? Participants who answered no to all questions were considered to not have any social support.

Statistical analysis

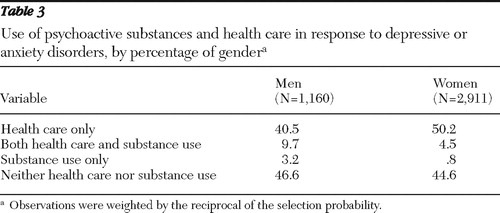

In order to adjust for differential representation, observations were weighted by the reciprocal of the selection probability ( 28 ).

First, frequencies of responses to psychological distress were calculated by gender for each disorder. Four types of responses were distinguished: using psychoactive substances (alcohol or illicit drugs), consulting a psychiatrist, consulting another medical doctor, and consulting another mental health professional (psychologist or psychotherapist).

Second, because these responses to disorders are not mutually exclusive, we combined health care and psychoactive substance use as follows: health care use only (without psychoactive substance use), psychoactive substance use only (without health care use), both health care and psychoactive substance use, and use of neither of them.

Health care was defined as consultation with a psychiatrist, another medical doctor, or another mental health specialist. We combined provider types into a single health care category because we were interested in the act of seeking help with a mental health professional, regardless of the specialty. The main question this article examined was the use of psychoactive substances in response to psychiatric disorders, and we wanted to compare this type of substance use to an "appropriate" response. Frequencies of use were calculated without considering each disorder separately. If a participant had several disorders, we determined that he or she had used health care if he or she had done so for at least one disorder and that he or she had used substances if he or she had done so for at least one disorder. Thus a participant who had used health care for a given disorder and substances for another one was classified in the group of those using both health care and substances.

Finally, we studied factors associated with the four categories of substance and health care use with a multinomial logistic regression, which allows the analysis of a qualitative dependent variable with several levels ( 29 ). Each level of the variable is compared with a reference level, for which the odds ratios for each covariate are supposed to be equal to one. In our study, this reference level was "health care use only." Covariates were age, gender, size of the town, region, country of birth, matrimonial status, education level, housing ownership, social support, type of disorder (depressive, anxious, or both), and disability. A participant with several disorders was classified as having severe disability if he or she scored as having severe disability for at least one of the disorders. Covariates were selected according to a stepwise descending procedure, and an association was considered as being significant when the p value was less than .05. Nonsignificant variables were not kept in the final model unless they appeared as confounding factors. Finally, interactions were tested between selected covariates. These analyses were performed using SAS proc surveymeans and proc surveylogistic.

Results

Of the 59,836 phone numbers randomly generated, 38,612 belonged to households. Among these households, 28,243 were available for the second step of the selection (proportion of contacted households 73.1%).

After selection of the participant in the household, 2,795 could not be contacted after 15 calls, 2,114 did not wish to participate, 610 were absent for a long period, 1,357 persons did not meet inclusion criteria, 702 were considered to be unable to complete the interview, and 588 did not complete the entire interview. Thus 20,077 participants completed the interview (response rate among contacted households 71.1%). Among them, 4,301 suffered from a probable 12-month anxiety or depressive disorder. Of them, 230 had a 12-month substance use disorder and were excluded. The final sample size was thus 4,071. [A flowchart showing the selection procedure is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

The sample is described in Table 1 . Major depressive episode was the most frequent psychiatric disorder found, with a 12-month prevalence estimate of 40.8% ( Table 1 ). Among anxiety disorders, the most frequent was specific phobia (35.1%). More than half of those having a depressive disorder also had a comorbid anxiety disorder.

|

Among men, frequency of substance use in response to a depressive or anxiety disorder was 12.9% ( Table 2 ). Substance use was more frequent for a major depressive episode, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or PTSD (all more than 10.0%). Substance use was less frequent than health care use, regardless of the type of care provider.

|

Frequency of substance use was lower among women (5.2%) than among men ( Table 2 ). As observed among men, substance use was more frequent for a major depressive episode, an obsessive-compulsive disorder, or a posttraumatic stress disorder and was less frequent than health care use, regardless of the type of care provider.

Substance use, health care use, and use of both in response to anxiety or depressive disorders are presented in Table 3 . Among women, the greatest proportion used health care only, whereas among men, the greater proportion used neither substances nor health care. Men and women used both health care and psychoactive substances more frequently than they used psychoactive substances alone.

|

Adjusted odd ratios (ORs) of factors associated with responses to anxiety or depressive disorders are presented in Table 4 . Compared with those who used health care only, those who used both health care and substances were more frequently men (OR=2.8), more often aged between 18 and 29 (OR=1.6) or between 30 and 49 (OR=1.7), and less likely to have a depressive disorder only (OR=.5).

|

Compared with those who used health care only, those who used substances only were more likely to be men (OR=5.1), aged between 18 and 29 (OR=3.3) or between 30 and 49 (OR=2.4), and single (OR=1.9).

Finally, compared with those who used health care only, those who used neither substances nor health care were more likely to be men (OR=1.2), to be aged between 18 and 29 (OR=1.7), and to not have a bachelor's degree (OR=1.3), and they were less likely to be single (OR=.7). They were less likely to have a depressive episode (with or without an anxiety disorder) and less likely to have a severe disability (OR=.5 for both).

Social support, size of town of residence, region, country of birth, and housing ownership were not significantly associated with health care use or substance use and were not confounding factors.

Discussion

Interpretation of results

The objectives of the study presented here were to estimate by gender the frequency of use of psychoactive substances and of health care in response to anxiety or depressive disorders and to determine factors associated with these behaviors. Data were collected with a large population-based survey.

The most frequent response to a probable anxiety or depressive disorder was consultation with a medical doctor. In France, general practitioners can either treat patients who have psychiatric disorders or refer them to a psychiatrist. People can also consult a psychiatrist or a psychologist without consulting a general practitioner first. However, despite universal health coverage, the copay is often higher for psychiatrists than for general practitioners, and consultations with other mental health providers are not reimbursed ( 30 , 31 ). This could explain why consulting with a medical doctor was the most frequent response to anxiety or depressive disorders and why consulting with a psychiatrist was more frequent than consulting with a psychologist or a psychotherapist.

Our study showed that substance use in response to anxiety or depressive disorders was common in both genders (around 13% for men and 5% for women). It was more frequent among men, a finding that is in line with gender inequality regarding substance use in general ( 9 , 19 , 32 ). In a study by Ramage-Morin ( 16 ), 18% of participants with panic disorder used alcohol in response to stress, which is larger than the frequencies calculated in our study. This can be explained by our study's excluding persons with a substance use disorder, by using different sampling procedures, and by using different questions. In our study, participants with a panic disorder were asked whether they used alcohol or drugs when they experienced panic attacks. By contrast, in Ramage-Morin's study, participants were asked whether they used alcohol in response to stress. Because stress is more frequent than panic attacks, occasions to drink are also more frequent. Moreover, because panic attacks are more severe and more frightening than stress, they might trigger health care use rather than use of alcohol. In addition, our study found that substance use was more frequently combined with health care among women than among men, which is concordant with previous studies showing that women used mental health care more often or more easily than men ( 33 , 34 ).

We have also shown that, in most cases, participants who used substances also used health care. In the multivariate analysis, men, single persons, and those aged 29 or younger were more likely to use psychoactive substances (either with or without health care) than health care alone. The greater use of psychoactive substances by young people has already been reported ( 3 ). In our study, associations between type of psychiatric disorders and responses to them correspond with those described in the literature. For example, our study showed that participants with an anxiety disorder were less likely to use health care than those with a depressive disorder, and other studies ( 33 , 34 , 35 ) have shown similar findings. Finally, our study showed that those who used neither substances nor health care were more likely to be young and to not have a bachelor's degree and were less likely to be single and to have a depressive disorder. Similar results have been found in studies addressing unmet needs for mental health care ( 33 , 34 ). Moreover, our study showed that the likelihood of using neither psychoactive substances nor health care increased when participants did not experience severe disability. This is concordant with studies showing that disorder severity is linked to a higher likelihood of health care use ( 36 ).

Limitations

Some limitations of our study have to be acknowledged. First, the sample was composed of persons who owned a land-line phone, which implies that they had a house, had enough money to own a phone, and were stable enough to be reached within 15 calls. They are thus not representative of the whole French general population, especially nowadays since about 10% of the population owns only a mobile phone according to the European Commission. We can deduce that participants in our study were less often single and had higher incomes than the general population. These factors are known to be linked to mental disorders (substance related or not) and to health care use ( 5 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 37 ). This might have resulted in an underestimation of 12-month prevalences of mental disorders, an underestimation of frequencies of psychoactive substance use, and an overestimation of frequencies of health care utilization. However, psychiatric disorder prevalence estimates in our study were higher than those found in the French data of the ESEMeD survey ( 38 ). In order for these potential problems in overestimating or underestimating to lead to a bias in the multivariate analysis, they would have to affect differentially the four groups defined by the dependant variable, which was certainly not the case. Thus the associations we studied were not biased by the lack of representativeness of our sample.

Probabilities of anxiety or depressive disorders were determined with the CIDI-SF, which has been shown to measure these disorders with good accuracy, except for generalized anxiety ( 24 ). This is why generalized anxiety disorder was not taken into account in our study.

For the purposes of our study, we theorized that a psychiatric disorder, as determined with the CIDI-SF, implied a mental health care need, which is not necessarily the case. This criterion for mental health care need is the most frequently used, although it has been criticized in the literature ( 10 , 39 , 40 , 41 ). Disability is one of the criteria that might improve the criterion of health care need for most disorders that we studied ( 23 ).

Substance use was based on participant report, raising the question of its validity, which has been repeatedly addressed in the literature ( 42 , 43 , 44 ). Participants were asked whether they used alcohol or illicit substances in order to deal with their disorder. However, they might not have been entirely aware of the reasons for their use. When distressed, they might look for settings where substances are used without recognizing that they are looking for the substances themselves. For instance, someone might recognize that he or she goes out with friends in bars to alleviate his distress, but denies that he or she then drinks more alcohol than usual because of the distress. This could lead to an underestimation of alcohol use as a response to psychological distress. Despite these limitations, participant report was the only way to collect data on such a behavior. Gathering data by giving participants a questionnaire, as opposed to conducting a phone interview, could have limited desirability bias but would have led to several missing data.

Chronology between the various responses to disorders was not available, although it would be important to know which one was chosen first. Among participants who used psychoactive substances and health care, risk of substance abuse or dependence might be different between those who used health care first and those who used substances first. The former might have used psychoactive substances because health care did not bring relief.

In the multivariate analysis, we did not distinguish the different health care providers, although they are likely to provide different types of care. However, we were interested in the comparison between substance use and health care use, because health care use is the most expected behavior in response to a psychiatric disorder by biomedical standards. We also did not consider other ways of help seeking, such as alternative medicine, hobbies, or meditation. In turn, the group of participants who used neither substances nor health care was heterogeneous, because it could comprise participants who were not aware of their disorders, as well as participants who chose responses to disorders that we did not investigate. Finally, in this analysis, we did not take into account income, which is known to be linked to mental disorders ( 37 ), because this variable was missing too frequently. We took into account housing ownership and education level, the combination of which has been shown to be a good indicator of income level ( 45 ).

Conclusions

Our study may have important public health implications. It has demonstrated that the use of substances in response to psychological distress is more frequent among young adults, men, and persons who are single. However, when persons have an anxiety disorder, this use is less often associated with health care use. We could thus define two profiles of persons who use substances in response to psychological distress, depending on whether they also used health care. For the former, prevention of substance use disorders could be achieved through medical care. For the latter, prevention of substance use disorders has to be targeted in another way, yet to be found.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The survey was ordered by the Direction de l'Hospitalisation et de l'Organisation des Soins and the Direction Générale de la Santé (DGS). It was funded by the DGS. The Conseil Régional d'Aquitaine supported a part of this study through grant number 2005-1301010A.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al: Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807–816, 2004Google Scholar

2. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, et al: The epidemiology of DSM-IV panic disorder and agoraphobia in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:363–374, 2006Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:593–602, 2005Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Jin R, et al: The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:415–424, 2006Google Scholar

5. Pirkola SP, Isometsa E, Suvisaari J, et al: DSM-IV mood, anxiety and alcohol use disorders and their comorbidity in the Finnish general population: results from the Health 2000 Study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 40:1–10, 2005Google Scholar

6. Sandanger I, Nygard JF, Ingebrigtsen G, et al: Prevalence, incidence and age at onset of psychiatric disorders in Norway. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:570–579, 1999Google Scholar

7. Karam EG, Mneimneh ZN, Karam AN, et al: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders in Lebanon: a national epidemiological survey. Lancet 367:1000–1006, 2006Google Scholar

8. Jacobi F, Wittchen HU, Holting C, et al: Prevalence, co-morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population: results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS). Psychological Medicine 34:597–611, 2004Google Scholar

9. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al: Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl 420:21–27, 2004Google Scholar

10. Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, et al: The treatment gap in mental health care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82:858–866, 2004Google Scholar

11. Kessler RC: Psychiatric epidemiology: selected recent advances and future directions. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78:464–474, 2000Google Scholar

12. Khantzian EJ: The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry 142:1259–1264, 1985Google Scholar

13. Khantzian EJ: The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 4:231–244, 1997Google Scholar

14. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Wallach MA: Dual diagnosis: a review of etiological theories. Addictive Behaviors 23:717–734, 1998Google Scholar

15. Jorm AF, Medway J, Christensen H, et al: Public beliefs about the helpfulness of interventions for depression: effects on actions taken when experiencing anxiety and depression symptoms. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 34:619–626, 2000Google Scholar

16. Ramage-Morin PL: Panic disorder and coping. Health Reports 15(suppl):31–43, 2004Google Scholar

17. Boys A, Marsden J, Strang J: Understanding reasons for drug use amongst young people: a functional perspective. Health Education Research 16:457–469, 2001Google Scholar

18. Bolton J, Cox B, Clara I, et al: Use of alcohol and drugs to self-medicate anxiety disorders in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 194:818–825, 2006Google Scholar

19. Blume SB: Gender differences in alcohol-related disorders. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 2:7–14, 1994Google Scholar

20. Encrenaz G, Messiah A: Lifetime psychiatric comorbidity with substance use disorders: does healthcare use modify the strength of associations? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41:378–385, 2006Google Scholar

21. Encrenaz G, Kovess-Masféty V, Sapinho D, et al: Utilization of mental health services and risk of 12-month problematic alcohol use. American Journal of Health Behaviors 31:392–401, 2007Google Scholar

22. Kish L: Survey Sampling. New York, Wiley, 1965Google Scholar

23. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

24. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, et al: The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7:171–185, 1998Google Scholar

25. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al: Sampling and methods of the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl 420:8–20, 2004Google Scholar

26. Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA: The measurement of disability. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 11 (suppl 3):89–95, 1996Google Scholar

27. Stephens T, Dulberg C, Joubert N: Mental health of the Canadian population: a comprehensive analysis. Chronic Diseases in Canada 20:118–126, 1999Google Scholar

28. Lee ES, Forthofer RN, Lorimer RJ: Analysing Complex Survey Data. London, Sage, 1989Google Scholar

29. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed. New York, Wiley, 2000Google Scholar

30. Verdoux H: The current state of adult mental health care in France. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 257:64–70, 2007Google Scholar

31. Verdoux H, Tignol J: Focus on psychiatry in France. British Journal of Psychiatry 183:466–471, 2003Google Scholar

32. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1994Google Scholar

33. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al: Use of mental health services in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl 420:47–54, 2004Google Scholar

34. Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al: Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:603–613, 2005Google Scholar

35. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

36. Harris KM, Edlund MJ: Use of mental health care and substance abuse treatment among adults with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services 56:954–959, 2005Google Scholar

37. Lahelma E, Laaksonen M, Martikainen P, et al: Multiple measures of socioeconomic circumstances and common mental disorders. Social Science and Medicine 63: 1383–1399, 2006Google Scholar

38. Lepine JP, Gasquet I, Kovess V, et al: Prevalence and comorbidity of psychiatric disorders in the French general population [in French]. Encephale 31:182–194, 2005Google Scholar

39. Jorm AF: National surveys of mental disorders: are they researching scientific facts or constructing useful myths? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40:830–834, 2006Google Scholar

40. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:617–627, 2005Google Scholar

41. Nelson CH, Park J: The nature and correlates of unmet health care needs in Ontario, Canada. Social Science and Medicine 62: 2291–2300, 2006Google Scholar

42. Babor T, Brown J, Del Boca FK: Validity of self-reports in applied research on addictive behaviors: fact or fiction? Behavioral Assessment 12:5–31, 1990Google Scholar

43. Finch E, Strang J: Reliability and validity of self-report: on the importance of considering context. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 51:269, 1998Google Scholar

44. Skog OJ: The validity of self-reported drug use. British Journal of Addiction 87:539–548, 1992Google Scholar

45. Oakes JM, Rossi PH: The measurement of SES in health research: current practice and steps toward a new approach. Social Science and Medicine 56:769–784, 2003Google Scholar