Quality of Depression Care and Its Impact on Health Service Use and Mortality Among Veterans

Depression affects nearly 30% of veterans, making it one of the most common chronic conditions treated in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) ( 1 ). Its impact on patient and system-level outcomes is substantial and well documented in the literature. Depression doubles the risk of mortality ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ) and is associated with poor emotional and physical outcomes, as well as increased health service use and cost ( 8 ).

Although clinical trials for depression show that antidepressant medications and psychotherapy are generally effective, less than half of patients with a depression diagnosis receive adequate treatment ( 9 , 10 , 11 ). Numerous initiatives to improve the quality of depression care are either under way or have already been completed ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). As part of these efforts, the VHA, along with other health care administrations, has endorsed clinical practice guidelines for depression treatment and established procedures and methods to measure quality of depression care ( 15 , 16 ).

Guideline-adherent care improves depression-related outcomes ( 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ), yet few studies have examined health service use, cost ( 21 ), and outcomes other than depression status (such as mortality and functional abilities). In studies that examined the relationship between quality of depression care and outcomes, antidepressant drug adherence was associated with increased medication adherence for comorbid conditions, decreased medical and psychiatric hospitalizations, and reduced total medical costs ( 21 , 22 ). Recent evidence suggests that practice-based depression interventions in primary care significantly decrease mortality over a five-year period ( 2 ). However, little evidence exists about whether depression care practices at the system level equate to changes in outcomes outside research-based interventions for patients.

The purpose of this investigation was to comprehensively determine the quality of depression care provided for patients with new-onset depression within the VHA over a six-year period. We sought to understand longitudinal trends in quality of depression care (specifically, the acute period after a new diagnosis) and to determine the overall effect of this level of quality on subsequent health service use and mortality.

Methods

Cohort

Using a variety of data sources—including VHA outpatient and inpatient treatment files and pharmacy benefits manager, as well as Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem and Social Security Administration death records—we constructed a database containing information from October 1999 through September 2005. Using the following methods, we extracted a final cohort of 205,165 patients with a new-onset depressive disorder who received at least one prescription for an antidepressant medication. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Baylor College of Medicine as well as the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center Research and Development Committee in Houston.

Construction of our cohort began with examination of all VHA outpatient records from fiscal years 1999–2005. Patients with an ICD-9-CM code for depression (296.2x, major depressive disorder, single episode; 296.3x, major depressive disorder, recurrent episode; 300.4, neurotic depression and dysthymia; or 311.0, depression not otherwise specified) were extracted (N=764,510). Each patient was then assigned a depression index date to reflect the first date of a depression diagnosis. We then restricted our cohort to patients with new-onset depression by examining the 365 days before the identified index date. Depression was classified as new onset if patients had no ICD-9-CM diagnosis for depression in the prior 365 days and they had received no prescription for an antidepressant between 31 and 365 days before their initial diagnosis. We determined that patients who received an antidepressant 30 days or less before their depression diagnosis had received this treatment in relationship to the episode identified, and we therefore reclassified their depression index date as the date of the medication fill. Applying the new-onset criteria reduced our cohort to 363,347. Antidepressant medications included tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants, and other antidepressants (including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), as described in prior studies ( 23 , 24 , 25 ).

Because our primary aims focused on provision of and follow-up care related to antidepressant medications, we restricted our sample to patients who had filled a prescription for an antidepressant (N=234,370). Finally, we excluded 3,149 patients who died during the first 180 days after the depression index date, 7,908 patients who had a large number of inpatient bed days (36 or more days during the 180 days postindex date), and 18,157 patients who had comorbid diagnoses of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Depression care quality measures

Methods for measuring and interpreting application of depression care guidelines vary widely. However, current guidelines and the literature suggest that quality measures of depression care related to antidepressant medication supply ratios and adequate follow-up are potentially important predictors of patient and health service use outcomes ( 15 , 21 , 22 , 26 ).

Adequate antidepressant supply

We dichotomized patients into categories representing adequate and inadequate supply of antidepressants. Supply was calculated for the number of days each patient was provided an antidepressant prescription (during the 84-day profiling period and based on pharmacy prescription fill data) divided by 84 days. Adequate supply of antidepressant medication, as in prior studies ( 10 , 23 ), was established as a patient's possession of medication (medication possession ratio) for 80% or greater of the total number of days in a given period. Overlapping antidepressants were not counted in the days' supply.

Adequate antidepressant follow-up visits

The definition of the adequate number of follow-up visits for monitoring antidepressant use has fluctuated in the literature between three visits within the 84-day period after diagnosis ( 22 ) and three visits after the initial diagnosis ( 10 ). We used a criterion of three visits after the initial diagnostic visit as the standard for adequate depression care ( 10 ), consistent with current Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set indicators. Follow-ups were dichotomized as adequate and inadequate. A depression follow-up encounter was defined by Current Procedural Terminology codes on the basis of the following: any psychiatric or mental health visit regardless of accompanying depression diagnosis, any non-mental health visit when a depression ICD-9-CM code accompanied the visit, and any telephone-based service for which a depression ICD-9-CM code accompanied the encounter.

Patient and other predictor variables

Several demographic and service use characteristics were used. Demographic factors included age, gender, race and ethnicity, marital status, and income (based on data from the Internal Revenue Service's average adjusted gross incomes by zip code). Race and ethnicity information was poorly populated in these national databases and therefore excluded from all predictive analyses.

Other information and health service characteristics from the medical record included patient service-connected disabilities; illness burden, represented by a relative risk (RR) score; and comorbid mental health conditions, which were restricted to anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use disorders. Because of increased access to care provided to veterans with service-related disabilities, we dichotomized patients into no service-connected disability or any service connection. Illness burden was assessed with a diagnosis-based, risk-adjustment methodology (DxCG Company, Boston) ( 27 ), which has been validated in the VA population ( 28 ). An individual's RR score is the patient's total predicted health care cost divided by the average predicted health care cost for the population, with a score of 1.0 reflecting average risk ( 27 , 28 ). RR score was broken down into tertiles with the following ranges: tertile 1, representing the lowest illness burden, .0–.6 (34.4%; N=68,423); tertile 2, .6–1.2 (33.3%; N=68,372); and tertile 3, representing the highest illness burden, 1.2–38.7 (33.3%; N=68,370).

Outcome variables

To assess the impact of quality of depression care on outcomes 12 months after new onset, we extracted variables related to all-cause mortality, inpatient hospitalizations (medical and psychiatric), and outpatient service use (primary medical care, surgical care, mental health care, urgent care, and ancillary or other care).

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe variables related to age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, income, illness burden, service-connected disability status, comorbid mental health diagnoses, adequate depression follow-up visits, adequate antidepressant medication supply, and 12-month outcome variables (relative to quality of depression care status, mortality, inpatient medical and psychiatric stays, and outpatient service use). To assess aggregate changes in quality of depression care over time, we examined the percentage of patients receiving adequate supply and adequate follow-up over time by using six-month intervals, and we subsequently tested for changes in study time periods by using Poisson regression analyses. Finally, logistic regression modeling procedures were used to predict inpatient medical stays, inpatient psychiatric stays, and 12-month all-cause mortality. To control for multiple logistic regression tests, a Bonferroni correction was used for data interpretation (p<.05 divided by three tests) and resulted in a significance threshold of .01.

Results

Total cohort

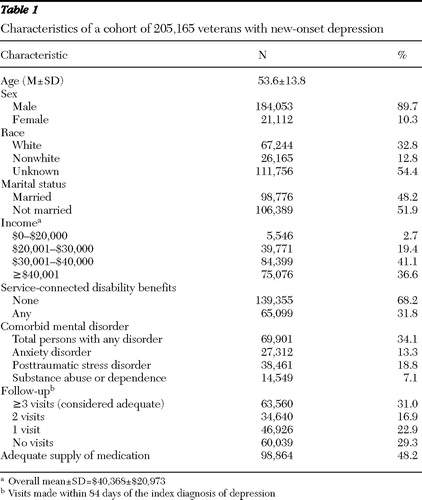

Table 1 shows the demographic composition of the cohort and summary measures of service use during the 84-day period after the depression index date. The cohort was predominantly male (89.7%), and mean±SD age was 53.6±13.8. Less than half of the veterans were married (48.2%), and mean income was $40,368±$20,973. RR score for the cohort was 1.3±1.5, indicating a slightly higher illness burden than that of the average VHA service user. RR scores were also divided into tertiles for analysis. In terms of service-connected disability status, 68.2% of the cohort did not have this status, and 31.8% were documented to have a service-connected disability of 1% or greater. Comorbid mental disorders had been diagnosed for 34.1% of the patients, specifically anxiety, 13.3%; PTSD, 18.8%; and substance use disorder, 7.1%.

|

In regard to follow-up care for depression, 31.0% of the cohort had adequate follow-up with three or more visits, 16.9% had only two follow-up visits, 22.9% had only one visit, and 29.3% had no visits. Analysis of supply of antidepressant medication showed that 48.2% had a medication possession ratio of 80% or greater, classified as having adequate supply.

The 12-month mortality rate was 1.9% (however, we excluded 7,732 patients who died within six months of the depression index date). Service use characteristics at the 12-month follow-up revealed that 7.4% (N=30,586) of the cohort had one or more inpatient medical stays, and 3.9% (N=16,052) had one or more inpatient psychiatric stays. Outpatient service visits at the 12-month follow-up were as follows: primary medical care, 6.4±8.0; surgery, 5.1±6.7; mental health, 20.5±69.1; urgent care, 2.7±3.1; and ancillary and other services (such as for laboratory tests), 16.4±28.2.

Adequate supply and follow-up over time

Examining six-month intervals after the index diagnosis, we found that the percentage of patients with an adequate supply of medication ranged from 48% in October 1999 to 52% by April 2002 and remained close to this level for the remaining periods. Poisson regression confirmed that no time period was significantly different from the final time period (April 2005).

Thirty-six percent of patients had adequate follow-up at the first period, October 1999, but this declined steadily to 27% in April 2003. The percentages then increased over the remaining four periods, to 33% in April 2005. Poisson regression showed that follow-up care at the April 2005 time point was significantly better than care at the April 2003 time point ( χ2 =4.55, df=1, p=.03).

Adequate care and its relationship to service use and mortality

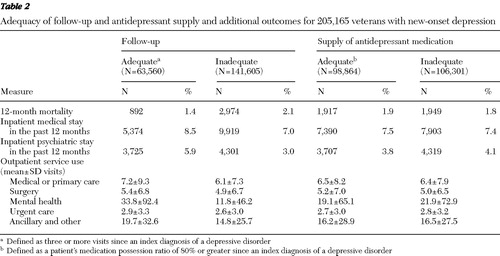

Table 2 shows summary measures for the cohort, with patients classified into adequate and inadequate follow-up visits and supply of antidepressant medication. Outpatient service use for the patients with adequate and inadequate follow-up was similar for primary medical care, surgery, urgent care, and ancillary and other care. Outpatient mental health service use was nearly three times higher among those who received adequate follow-up (33.8±92.4 visits 12 months after the index dates) compared with those who received inadequate follow-up (11.8±46.2 visits). Of those with adequate follow-up, 8.5% had one or more inpatient medical stays and 5.9% had an inpatient psychiatric stay, whereas for those with inadequate follow-up 7.0% had one or more inpatient medical stays and 3.0% had an inpatient psychiatric stay. Mortality was lower for those with adequate follow-up (1.4% versus 2.1%).

|

Comparisons of veterans with adequate and inadequate medication supply for depression suggest that both outpatient and inpatient service use in the two groups was similar for primary medical care, surgery, urgent care, mental health care, and ancillary and other care. Similarly, no differences were noted between these two subgroups in 12-month mortality.

Prediction of service use and 12-month mortality

Separate logistic regressions were conducted to determine which patient and clinical care factors (age, illness burden as measured by RR score, frequency of primary medical care visits, adequate follow-up care for depression, and adequate supply of antidepressant medication) predicted inpatient medical care, inpatient psychiatric care, and 12-month mortality.

Inpatient medical care

For this model, significant predictors were RR score and adequate follow-up ( Table 3 ). Patients with the highest illness burden (RR score in the third tertile) were 2.1 times as likely to use inpatient services (odds ratio [OR]=2.10). The healthiest, with RR score in the first tertile, were 22% less likely to use services (OR=.79) relative to patients in the second tertile. Adequate follow-up and number of outpatient primary medical care visits had modest effects (OR=1.09 and OR=1.06, respectively), suggesting that increases in these variables equated to more inpatient service use.

|

Inpatient psychiatric care

The largest significant predictor of inpatient psychiatric care was presence of comorbid mental disorders (OR=3.47) ( Table 3 ). Other important predictors were RR score (highest tertile) (OR=1.67) and adequate follow-up (OR=1.38). Veterans in the lowest RR score tertile showed a modest increase in use of inpatient care (OR=1.08); primary medical care visits were also a modest predictor of inpatient care (OR=1.01). For each increasing year of age, odds of inpatient psychiatric use decreased by 4% (OR=.96).

Twelve-month mortality

Significant predictors of 12-month mortality were age, RR score, and adequate follow-up ( Table 3 ). The most ill patients (third tertile) were 2.5 times more likely to die, and the healthiest were 13% less likely to die (relative to patients in the second tertile). Notably, adequate follow-up had a protective effect on mortality (OR=.86). Each year of age increased risk of mortality by 6% (OR=1.06). Neither adequate supply nor number of outpatient primary medical care visits significantly affected mortality.

Discussion

In this study we found, after controlling for illness burden and frequency of non-mental health clinical visits, that adequate follow-up for new-onset depression in the VHA was significantly associated with decreased likelihood of mortality. Despite prior reports of potential decreased inpatient service use after receipt of adequate depression care ( 22 ), our findings suggest that provision of adequate care is associated with increased cost to the system, both in terms of inpatient and outpatient services, particularly for mental health service use.

The relationship between adequate follow-up visits for depression care and decreased mortality is consistent with a recent randomized controlled trial that found that care for depression (monitoring medication adherence, side effects, and depressive symptoms) compared with usual care practices reduced mortality over a five-year period ( 2 ). Data from our study suggest that the provision of three or more follow-up visits (which likely contained management components similar to the study by Gallo and colleagues [2]) appears to be related to decreased 12-month mortality. Although these findings are preliminary, they are notable given the large sample and the real-world practice data presented.

Our longitudinal analysis found few changes in quality of depression care over time. We found few or no changes in adequate supply of antidepressant medications but modest yet statistically significant changes in adequate follow-up toward the end of the study period. We speculate that the more recent changes seen may have been a delayed response related to the VHA's adoption of depression performance measures in 2000 ( 16 ), which specifically targeted improved follow-up care for patients newly diagnosed as having depression. However, these notable policy- and system-level efforts to improve quality of depression care within the VHA did not translate into better provision of antidepressant medication. The delayed response in adequate depression follow-up, although speculative, is probable given the difficulty in implementing and obtaining changes from a new performance measure and the sheer size of the VHA health care system.

Previous examinations of quality of depression care practices in integrated health care systems such as the VHA have found adequate antidepressant dosage for over 90% of patients, with 10% to 45% receiving adequate antidepressant medication ( 22 , 24 , 26 , 29 ) and between 23% and 62% of patients receiving guideline-recommended follow-up care ( 22 , 24 , 26 ). Our findings differ from those of other researchers in the area, most notably, those of Charbonneau and colleagues ( 9 ). These differences may be explained by cohort size and geographic region of study, limited time periods, depression definition (for example, acute stage versus all depression cases, regardless of onset), and definition of adequate follow-up (two visits or three). This study's methods are believed to be the best available, with inclusion of a large and nationally representative VHA cohort, data from multiple years of service, and a specific focus on new-onset depression cases, with patients receiving at least one antidepressant prescription (increasing the odds that cohort patients were seeking depression care through the VHA). This study is also the first known study to examine and assess the impact of quality of depression care on mortality at the health care system level.

Generalizability of this study is limited not only by the VHA sample, skewed in terms of gender, but also by the large and well-integrated nature of this system; reliance on diagnosed depression and inability to measure and control for depression severity; and restricted data, which did not include mental health care provided outside the VHA. Although recent work suggests that reliance on administrative diagnoses often excludes undiagnosed patients with significant, treatable symptomatology ( 25 ), another study found that the use of depression diagnoses from administrative databases is largely specific but lacks sensitivity ( 30 ). Other notable limitations include our inability to control for race and ethnicity, failure to assess non-medication-based treatments (such as psychotherapy), and our mortality inclusion and exclusion criteria, so that patients who died during the first 180 days after diagnosis were not included in the analyses. In response to these limitations, our exclusionary rules (such as restrictions for death and use of a high number of inpatient days) focused on improving internal control and increasing the odds that patients included in this investigation were likely to receive depression care through the VHA and were able to obtain adequate outpatient depression care.

Conclusions

High-quality health care for depression is important. Health care systems are faced with many challenges in regard to mental health care, including timely recognition of depression and meeting antidepressant medication treatment guidelines for adherence. Studies have shown that depression remains undetected in 30% to 70% of primary care patients, with smaller numbers receiving treatment and even smaller numbers receiving guideline-adherent care ( 12 , 25 ).

Quality of depression care is attributable not only to facets of the health care system but also to provider and patient factors ( 31 ). Providers frequently face competing demands to address divergent multisystem patient difficulties within an abbreviated office visit ( 32 ), may not possess adequate mental health knowledge or training, and may have negative beliefs about mental health conditions and treatment. Patients also face salient barriers that limit the amount of high-quality depression care provided within health care settings ( 32 ) and likely contribute to high discontinuation rates for antidepressant medications within the first month of diagnosis ( 33 ). For example, patients may lack insight or knowledge about symptoms of mental illness (especially when comorbid with other physical conditions), have negative attitudes about depression and its treatment (such as stigma and concerns about medication side effects, including addiction potential) ( 32 , 33 , 34 ), and vary in their ability or willingness to self-manage their medical and mental conditions. Future studies are needed to determine the effect of patient factors on care-seeking behavior and treatment engagement, which likely affect the provision of high-quality depression care and the subsequent cost of this care.

Evidence-based quality improvements for depression care are difficult to implement at the system level, even under the auspices of standardized research training and monitoring ( 34 ). Future quality improvement efforts are most likely to succeed if a triadic focus is used so that patients, providers, and systems receive targeted change strategies. For example, few if any studies of quality of depression care examine or control for the role of patients' attitudes, beliefs, and preferences about care, which are critical to understand for continued program improvements. At the provider level, increased training to improve recognition skills and comfort in identifying and referring patients with depression are likely to increase recognition, and system-level improvements may include increased time allocation for mental health assessments and increased resources (and referral networks), such as personnel and computer-based communication systems ( 35 ).

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Cully is a recipient of a VA CDA-2 Award (grant number 05-288) from the VHA Health Services Research and Development Service. Dr. Petersen was a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar (grant number 045444) when this work was conducted and is an American Heart Association Established Investigator award recipient (grant number 0540043N). The authors gratefully acknowledge the input and work of Mark Kunik, M.D., M.P.H., and Louise Henderson, Ph.D., M.S.P.H., and Tracey Urech, M.P.H., in the development of this work. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the VA.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Hankin CS, Spiro A, Miller DR, et al: Mental disorders and mental health treatment among US Department of Veterans Affairs outpatients: the Veterans Health Study. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1924–1930, 1999Google Scholar

2. Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, et al: The effect of a primary care practice-based depression intervention on mortality in older adults: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 146:689–698, 2007Google Scholar

3. Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, et al: Depression, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and two-year mortality among older, primary-care patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13:748–755, 2005Google Scholar

4. Schulz R, Drayer RA, Rollman BL: Depression as a risk factor for non-suicide mortality in the elderly. Biological Psychiatry 52:205–225, 2002Google Scholar

5. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF III, et al: Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291:1081–1091, 2004Google Scholar

6. Bruce ML, Leaf PJ: Psychiatric disorders and 15-month mortality in a community sample of older adults. American Journal of Public Health 79:727–730, 1989Google Scholar

7. Pennix BW, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJ, et al: Minor and major depression and the risk of death in older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:889–895, 1999Google Scholar

8. Donohue JM, Pincus HA: Reducing the societal burden of depression: a review of economic costs, quality of care and effects of treatment. Pharmacoeconomics 25:7–24, 2007Google Scholar

9. Charbonneau A, Rosen AK, Ash AS, et al: Measuring the quality of depression care in a large integrated health system. Medical Care 41:669–680, 2002Google Scholar

10. Jones LE, Turvey C, Carney-Doebbeling C: Inadequate follow-up care for depression and its impact on antidepressant treatment duration among veterans with and without diabetes mellitus in the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of General Hospital Psychiatry 28:465–474, 2006Google Scholar

11. Weilburg JB, Stafford RS, O'Leary KM, et al: Costs of antidepressant medications associated with inadequate treatment. American Journal of Managed Care 10:357–365, 2002Google Scholar

12. Rost K, Dickinson ML, Fortney J, et al: Clinical improvement associated with conformance to HEDIS-based depression care. Mental Health Services Research 7:103–112, 2005Google Scholar

13. Levkoff SE, Chen H, Coakley E, et al: Design and sample characteristics of the PRISM-E multisite randomized trial to improve behavioral health care for the elderly. Journal of Aging and Health 16:3–17, 2004Google Scholar

14. Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Petzel R: Applying evidence from depression quality improvement research to VA. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Quarterly 3:2–4, 2002Google Scholar

15. HEDIS 2006. Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, vol 2, Technical Specifications. Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2005Google Scholar

16. VA/Department of Defense Evidence Based Clinical Practice Guideline Working Group: Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults in the Primary Care Setting. Pub no 10Q-CPG/MDD-00. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration and Health Affairs, and Department of Defense, Office of Quality and Performance, May 2000Google Scholar

17. Hepner KA, Rowe M, Rost K, et al: The effect of adherence to practice guidelines on depression outcomes. Annals of Internal Medicine 147:320–329, 2007Google Scholar

18. Revicki DA, Simon GE, Chan K, et al: Depression, health-related quality of life, and medical cost outcomes of receiving recommended levels of antidepressant treatment. Journal of Family Practice 47:446–452, 1998Google Scholar

19. Sood N, Treglia M, Obenchain RL, et al: Determinants of antidepressant treatment outcome. American Journal of Managed Care 6:1327–1336, 2000Google Scholar

20. Sobocki P, Ekman M, Agren H, et al: Health-related quality of life measured with EQ-5D in patients treated for depression in primary care. Value in Health 10:153–160, 2007Google Scholar

21. Katon W, Cantrell CR, Sokol MC, et al: Impact of antidepressant drug adherence on comorbid medication use and resource utilization. Archives of Internal Medicine 165:2497–2503, 2005Google Scholar

22. Charbonneau A, Rosen AK, Owen RR, et al: Monitoring depression care: in search of an accurate quality indicator. Medical Care 42:522–531, 2004Google Scholar

23. Charbonneau A, Parker V, Meterko M, et al: The relationship of system-level quality improvement with quality of depression care. American Journal of Managed Care 10:846–851, 2004Google Scholar

24. Jones LE, Turvey C, Torner JC, et al: Nonadherence to depression treatment guidelines among veterans with diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Managed Care 12:701–710, 2006Google Scholar

25. Liu C, Campbell DG, Chaney EF, et al: Depression diagnosis and antidepressant treatment among depressed VA primary care patients. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 33:331–341, 2006Google Scholar

26. McCarthy JF, Bambauer KZ, Austin K, et al: Treatment for new episodes of depression. Psychiatric Services 58:1035, 2007Google Scholar

27. Ellis RP, Pope GC, Iezzoni L, et al: Diagnosis-based risk adjustment for Medicare capitation payments. Health Care Financing Review 17:101–128, 1996Google Scholar

28. Petersen LA, Pietz K, Woodard LD, et al: Comparison of the predictive validity of diagnosis-based risk adjusters for clinical outcomes. Medical Care 43:61–67, 2005Google Scholar

29. Busch SH, Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA: Comparing the quality of antidepressant pharmacotherapy in the Department of Veterans Affairs and the private sector. Psychiatric Services 55:1386–1391, 2004Google Scholar

30. Cully JA, Jimenez D, Ledoux T, et al: Recognition and treatment of depression and anxiety symptoms in heart failure. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry Primary Care Companion, in pressGoogle Scholar

31. Klinkman MS: Competing demands in psychosocial care: a model for the identification and treatment of depressive disorders in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry 19:98–111, 1997Google Scholar

32. Nutting PA, Rost K, Smith J, et al: Competing demands from physical problems: effect on initiating and completing depression care over 6 months. Archives of Family Medicine 9:1059–1064, 2000Google Scholar

33. Cantrell CR, Eaddy MT, Shah MB, et al: Methods for evaluating patient adherence to antidepressant therapy: a real-world comparison of adherence and economic outcomes. Medical Care 44:297–299, 2006Google Scholar

34. Rubenstein LV: Improving care for depression: there's no free lunch. Annals of Internal Medicine 145:544–546, 2006Google Scholar

35. Rush AJ: STAR*D: what have we learned? American Journal of Psychiatry 164:201–204, 2007Google Scholar