Efficacy of the Team Solutions Program for Educating Patients About Illness Management and Treatment

Psychoeducation may be defined as the education of a person with a psychiatric disorder in subject areas that serve the goals of treatment and rehabilitation ( 1 ). Intended outcomes of psychoeducation fall along a continuum and build upon one another. Basic outcomes include knowledge acquisition and comprehension, which may lead to better insight and illness management. Practice guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia recommend the use of psychoeducation ( 2 , 3 , 4 ), including patient and family education about the nature of schizophrenia, its treatment, coping and management strategies, and knowledge and skills needed to avoid relapse. Patient and family education is recommended throughout all phases of treatment ( 3 , 5 ).

Although psychoeducation is recommended as part of standard practice in treating individuals with schizophrenia, it has not been clear how best to provide it and whether it actually improves knowledge of schizophrenia or changes behavior ( 2 , 6 ). Nevertheless, an accumulating body of evidence indicates that psychosocial interventions that include psychoeducation as a key feature can provide an important adjunct to the pharmacological treatment of persons with schizophrenia ( 7 , 8 , 9 ). These methods have many common elements and are now frequently referred to as "illness management" approaches. Illness management has been recommended for general dissemination in routine treatment settings by several authors ( 4 , 6 , 10 , 11 ). Major common features of illness management include an emphasis on structured education regarding symptom recognition and medication management in addition to education and training in the use of coping skills to effectively manage symptoms and prevent relapse ( 7 ).

Despite evidence of the effectiveness of illness management, such approaches are rarely used in routine mental health treatment settings in the United States ( 10 , 11 ). Tarrier and colleagues ( 12 ) suggested that the introduction of effective psychosocial interventions into routine care has been slow because of several barriers, including lack of partnership between researcher and clinician; absence of appropriate knowledge and clinical skills; and organizational characteristics, such as lack of leadership or competing demands, that may constrain new developments. Psychosocial approaches that can improve treatment outcomes as well as be implemented easily in routine care settings are needed to overcome some of these barriers.

The Team Solutions treatment model ( 13 ) was developed by psychiatric researchers, advocates, and clinicians with support from Eli Lilly and Company in an attempt to create a free and easily accessible psychoeducational approach to illness management for people with major mental illnesses. It is a modular psychoeducational program that covers a series of topics associated with recovering from, and managing, mental illness. Topics include understanding the symptoms of mental illness, why and how psychiatric medications work and are an important part of treatment, relapse prevention and coping strategies, and how to avoid crisis. The program was designed for use by mental health professionals and paraprofessionals in individual and group settings and has been disseminated in routine mental health treatment settings ( 14 ). The materials may be downloaded from the Internet and used without a fee.

In the interest of full disclosure, several authors of this study, through a university-based training initiative sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company, train behavioral health care personnel at agencies across the United States in this approach. The investigators sought to study the efficacy of the program because, despite the use of an expert panel in developing the program and face validity of the materials, no data have been reported on the efficacy of Team Solutions as a treatment method. This study was also supported, in part, by Eli Lilly and Company.

The purpose of this investigation was to conduct a randomized controlled study of the efficacy of Team Solutions in a public-sector day hospital setting for patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Findings were evaluated with consideration of the viability of Team Solutions as a candidate for widespread implementation in routine treatment settings.

Methods

Setting and population

The study took place at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-University Behavioral HealthCare (a statewide mental health care delivery system at the university) from September 2002 through September 2003. Institutional review board approval for the study was received. Participants were recruited from three day treatment programs, which serve daily approximately 550 adults with a diagnosis of severe mental illness. At the time of the study, the programs offered psychosocial treatment that was primarily rooted in the psychiatric rehabilitation and clubhouse models ( 15 ), offering a mixture of involvement in prevocational work assignments, goal-oriented recreational groups, social skills training, and psychoeducational groups. Although some psychoeducational services were provided on medication and symptom management, these groups were not a major focus of the programs.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To meet criteria for inclusion in the study, potential participants had to be partial hospitalization clients who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, as confirmed by the treating psychiatrist, and who attended the partial hospitalization program at least two days per week. Potential participants were excluded if their clinical records indicated the presence of a comorbid diagnosis of dementia or mental retardation or if they showed evidence of severely impaired intellectual functioning on the Shipley Institute of Living Scale, were unable or unwilling to give informed consent, had been exposed to more than one Team Solutions workbook, or showed evidence of significant risk of suicide.

Participants

Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1 . Seventy-four clients volunteered to participate, but three of them were not included in the final analysis because of missing data for the primary outcomes at time 1. No data are available for the clients who did not volunteer for the study. The 71 volunteers met inclusion criteria and completed baseline measures for the study. As can be seen in Table 1 , the sample included in the study was diverse with regard to gender and ethnicity. The sample comprised older adults, with 85 percent between the ages of 35 and 64, who had mostly high school education; only 24 percent had more than a high school education. The demographic comparison between the control and experimental groups showed that differences were minimal, suggesting that randomization was successful. There was some nominal difference between the two groups with respect to years of education, which was statistically controlled for in the analyses (see Results section).

|

Study design

This was a randomized, single-blind study with two treatment groups. Participants meeting inclusion criteria were initially recruited through announcements at the treatment programs and told about the nature of the study. After informed consent was obtained, participants were randomly assigned to attend one of two groups: the experimental group, consisting of enrollment in four Team Solutions groups weekly, or the control group, consisting of continuation of treatment as usual. Randomization was based on a table of random numbers. Trained raters who were blind to the study group assignment conducted interviews with participants to complete outcome measures at baseline, eight weeks, and 24 weeks.

Treatments

Team Solutions. Participants assigned to the experimental group received the following intervention: Team Solutions groups met twice each day, two days per week, for a total of 24 weeks. There were three eight-week sessions, and two workbooks were covered concurrently during each eight-week session. Each Team Solutions group meeting ran for one hour. When participants assigned to the experimental group were not scheduled to be in their Team Solutions groups, they continued to participate in the same prevocational and treatment groups as they had before enrolling in the study. The first eight-week session covered the workbooks Understanding Your Illness and Recovering From Schizophrenia . The second eight-week session covered the workbooks Understanding Your Treatment and Getting the Best Results From Your Medication . The third eight-week session covered the workbooks Helping Yourself Prevent Relapse and Avoiding Crisis Situations . Team Solutions groups were facilitated by both regular staff employed by the day treatment programs and by psychology interns, externs, and postdoctoral fellows in training at the sites. All group facilitators received two days of intensive training in the Team Solutions psychoeducational approach before the study began.

Treatment as usual. Participants randomly assigned to the control group continued their treatment as usual, which consisted of all aspects of the day treatment programs in which they previously participated, including participation in prevocational work areas, goal-oriented recreational groups, social skills training, and psychoeducational groups on topics such as medication education, stress management, physical health issues, nutrition and exercise, and independent living skills.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome variable assessed in this study was knowledge. Three measures were used to assess this variable: the Knowledge About Schizophrenia Questionnaire (KASQ) ( 16 ), the Team Solutions comprehensive knowledge assessment scale (TSCKAS), and the Team Solutions Individual Workbook Knowledge Assessment. The KASQ is a 25-item self-report measure of general knowledge about schizophrenia that has been found to have good reliability—published alphas range from .85 to .89, and the alpha was .82 in this study—and sensitivity to change. The score for the KASQ was the number of correct responses and ranged from 0 to 25. The TSCKAS was developed for this study and was created by Patricia L. Scheifler, a Team Solutions content expert and author of several of the Team Solutions workbooks, and was derived from the workbooks' individual Team Solutions knowledge assessment scales. Scores on the TSCKAS range from 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating greater knowledge. Testing of the psychometric properties of this measure confirmed adequate reliability (alpha=.63) and a correlation of .73 with the KASQ. In addition, Team Solutions workbook knowledge assessments were administered before and after each of the experimental group's eight-week sessions.

Secondary outcome variables studied were medication adherence, social functioning, insight, quality of life, and psychiatric symptoms. Medication adherence was measured with the Treatment Compliance Interview (TCI). The TCI is a three-item self-report measure that assesses the degree of medication adherence in three areas: dosage deviation (scores range from 1 to 3), level of medication supervision (scores range from 1 to 5), and willingness to remain on medication (scores range from 1 to 3). Higher scores on the TCI indicate greater compliance. Symptoms were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia (PANSS) ( 17 ) and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) ( 18 ), which were rated by interviewers who were blind to the treatment assignment. Positive symptoms on the PANSS range from 7 to 49, negative symptoms from 7 to 49, and general psychopathology from 16 to 112, with higher scores indicating greater levels of symptoms. The CGI severity and CGI change scales range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating greater severity and worsening of symptoms. Functioning and quality of life were assessed with the Global Assessment of Functioning-Disability Scale (GAF-DIS) ( 19 ) and the Psychological General Well-Being Scale (PGWB) ( 20 ). The GAF-DIS, like the GAF, establishes ratings on a scale that ranges from 1 to 90, with higher scores indicating better functioning, but focuses exclusively on functioning rather than combining symptoms and functioning into one rating. The GAF-DIS has been found to be a reliable and valid approach to assess the functioning of persons with severe mental illness ( 21 ).

The PGWB is a 22-item self-report measure that assesses subjective well-being and quality of life. Subscales of the PGWB have dimensions such as anxiety (scores range from 0 to 25, with lower scores representing higher anxiety), depression (scores range from 0 to 15, with lower scores indicating more depression), positive affect (scores range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indexing better spirits), self-concept (scores range from 0 to 15, with higher scores representing greater concept of self), general health (scores range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating better health), and vitality (scores range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating better vitality). An overall index was also calculated from the PGWB (scores range from 0 to 110, with higher scores indicating greater psychological well-being). Insight was assessed with three items from the Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder ( 22 ): awareness of mental illness, awareness of the achieved effect of medication, and awareness of the social consequences of mental disorder. Each item has scores that range from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating the least possible insight. Combining the three items yields a total insight score ranging from 3 to 15, with higher scores indicating lower insight.

Tertiary outcome measures used were attitudes about recovery, attitudes about medication, and mastery and empowerment. Attitudes about recovery were assessed with the Recovery Attitudes Questionnaire (RAQ) ( 23 ). The RAQ is a seven-item self-report Likert scale that assesses attitudes about the potential for recovery and positive outcome from severe mental illness. The RAQ score ranges from 7 to 35, with lower scores indicating more appropriate attitudes. The RAQ has been found to have good reliability and validity properties. Attitudes about medication were assessed with the Rating of Medication Influences (ROMI) Scale ( 24 ). The ROMI Scale is a clinician-rated scale that measures positive and negative attitudes and influences related to adherence with antipsychotic medication. Two scores are calculated from the ROMI Scale. The first (ROMI-POS) assesses attitudes that measure better compliance with medication and is calculated by averaging the scores of the first nine items of the ROMI Scale. This composite ROMI-POS score ranges from 1 to 3. The ROMI-NEG score is calculated across the last ten items of the ROMI Scale and also has a score ranging from 1 to 3, although in this case higher ROMI-NEG scores portend worse compliance with medication. Finally, mastery and empowerment were measured by using the IAPSRS Toolkit from the International Association of Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services ( 25 ). The IAPSRS Toolkit is a 20-item self-report measure that contains items assessing four subscales: empowerment, mastery, life satisfaction, and program satisfaction. This measure has been tested as an outcome instrument in psychosocial rehabilitation programs and has been found to be reliable and valid. In this study, we used a single composite score based on the IAPSRS by averaging the responses on the 20 items. This composite score could range from 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater mastery and empowerment.

Analysis plan

Data were analyzed with a linear random coefficient regression model for repeated measures. The repeated measures in this case were the individual participants' scores on any given variable at each testing session (baseline, midpoint, and endpoint). This plan of analysis is in line with an intent-to-treat approach, albeit without requiring the use of "last observation carried forward" ( 26 ). This model was tested with the mixed procedure of SAS Version 8 estimation and the assumption of compound symmetry in the structure of repeated measures. Treatment (experimental versus control) was treated as a fixed effect, as was testing session (baseline, midpoint, and endpoint) and their interaction. For the two primary outcomes, on the KASQ and the TSCKAS, three covariates were added to the model to control for variables that tend to be predictive of scores on knowledge tests. The covariates were age of participant, years of education, and symptom severity as measured by the CGI. For any given outcome variable, the effect of most interest in testing the hypothesis that Team Solutions is beneficial relative to the control condition is the interaction of treatment and rating session.

Results

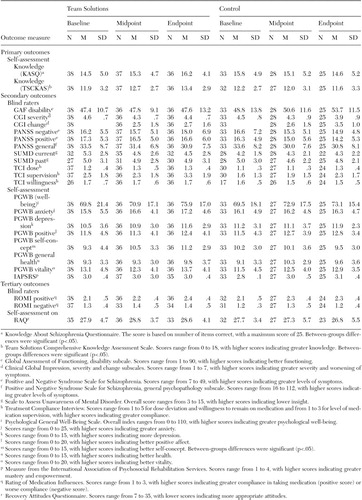

Attendance of individuals varied from 20 percent to 94 percent of the offered sessions. Mean attendance for the group was 73 percent. Other findings are summarized in Table 2 . As shown in the table, participants assigned to Team Solutions showed incremental gains on the KASQ relative to the control group, for which scores tended to decrease, hence the significant interaction. For the TSCKAS, the only significant effects in the mixed model were for severity (p<.02), where more severely symptomatic participants tended to have lower scores, and for the interaction of treatment and rating session (p<.01). The pattern of TSCKAS scores was similar to that of the KASQ. Participants in the Team Solutions group showed incremental gains, whereas those in the control group showed a steady decline. In summary, the data shown in Table 2 support the hypothesis about primary outcomes; that is, the Team Solutions program improved patients' knowledge about their illness. As shown in Table 2 , no other significant changes were observed, except for the self-concept subscale of the PGWB (p<.05). Table 3 shows the results of the knowledge testing for each workbook. All the differences were significant with paired t tests.

|

|

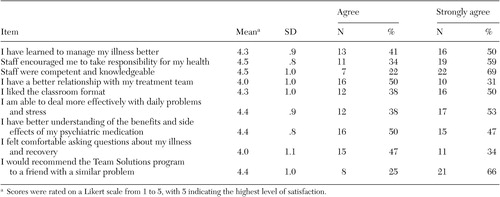

After the program, a nine-item anonymous satisfaction survey was administered. As shown in Table 4 , over 90 percent of clients agreed that they had learned to better manage their illness, roughly 93 percent agreed that staff encouraged them to take responsibility for their own health, and roughly 97 percent claimed they had a better understanding of the benefits and side effects of their medication. The following are examples of statements written by participants on the satisfaction surveys: "I like how you get better on your medication by knowing more about the medicine"; "There is a lot of information. I want more of this information"; "I look forward to coming every week"; and "We learn more. No one ever told me these things before."

|

Discussion

As a whole, the trial did not demonstrate that the Team Solutions program was beneficial to the patients studied with respect to clinical status. Although there was significant improvement in the primary outcome measure of knowledge about illness, the Team Solutions program did not demonstrate superiority over treatment as usual with respect to other outcomes, such as symptom severity, treatment adherence, and global functioning, and general attitudes toward self and recovery. The findings are discussed below in more detail, first for primary outcomes and subsequently for secondary and tertiary outcomes.

Primary outcomes

The Team Solutions program demonstrated statistically significant efficacy, compared with treatment as usual, with respect to the primary outcome measures of knowledge and understanding of illness, medication, and prevention of relapse and crises. The effects were significant even after the analysis controlled for years of education, age, and symptom severity. Gains were modest but observed for each of the three knowledge measures studied. These findings were observed in a relatively short span in a mature sample of participants, many with long treatment histories. Data from the anonymous satisfaction surveys of the experimental group indicated that participants were very satisfied with the service and found it helpful. Notably, participants reported a better understanding (4.4 on Likert scale of 1 to 5) of mental illness and also reported that they could deal more effectively with daily problems and stress.

Secondary and tertiary outcomes

With the exception of self-concept (discussed below), there were no positive findings with respect to the secondary and tertiary outcome measures. However, it is possible that more research is needed because no single study provides "proof" of the null hypothesis. Below we discuss possible considerations for future research.

Significant improvement in the construct of self-concept, as measured on the PGWB scale, was evident among participants who attended the experimental group, although such a result may have capitalized on chance. However, a limitation in study design prompts caution in interpreting this and other results of a self-report nature, as a single-blind study design is not configured to control for Hawthorne-type effects.

Limitations and considerations for future research

Several limitations of this study should be considered in designing future research. The relatively short time frame of our study may have limited the likelihood of observing any significant changes in outcomes other than knowledge. Also, the age range of the population studied is another important variable that needs to be considered. Eighty-four percent of the participants were in the 35- to 64-year age range, and many had been in mental health treatment for several years. Given that age has been found to be inversely related to change in social functioning in schizophrenia ( 27 ), the study of the effect of this intervention in a younger population may be warranted. Another possible limitation of this study is that the treatment-as-usual group received treatment in a university-based setting that specializes in treating people with severe mental illness. The treatment offered in this context may have been considerably more enriched than treatment that is available to most individuals with schizophrenia in the United States.

An additional consideration for future research is the effect that psychoeducational programs such as Team Solutions will have if combined with approaches such as motivational enhancement and cognitive-behavioral strategies. A systematic review of the literature examining psychosocial interventions for improving medication adherence found that psychoeducational interventions without accompanying behavioral components and supportive services were not likely to be effective ( 28 ). Similarly, a review of the research on illness management concluded that psychoeducation, behavioral tailoring in relapse prevention, and coping skills training that uses cognitive-behavioral techniques were all important components of comprehensive illness management ( 6 ).

Conclusions

Team Solutions is a modularized psychoeducational program aimed at improving knowledge regarding illness management and treatment for persons with schizophrenia. Despite improvement in knowledge about mental illness, this study failed to demonstrate that the Team Solutions program was superior to treatment as usual with respect to other important outcome measures studied, such as symptoms and functioning level. We conclude that psychoeducation by itself is unlikely to lead to significant gains in these outcomes, especially in an older population of people with schizophrenia. However, it remains to be seen whether Team Solutions or other psychoeducational programs might demonstrate advantages not observed in this particular study in other systems; in other populations, such as a younger sample; or when combined with other treatment approaches. Further research is warranted.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded in part by Eli Lilly and Company.

1. Pekkala E, Merinder L: Psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4:CD002831, 2001Google Scholar

2. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, 2nd ed. American Journal of Psychiatry 161 (Feb suppl):1-56, 2004Google Scholar

3. Treatment of schizophrenia 1999 (The Expert Consensus Guideline Series). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60 (suppl 11):3-80, 1999Google Scholar

4. Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, et al: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:193-217, 2004Google Scholar

5. Weiden PJ, Scheifler PL, McEnvoy JP, et al: Expert Consensus Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia: a guide for patients and families. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:1-8, 1999Google Scholar

6. Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton DW, et al: Illness management and recovery: a review of the research. Psychiatric Services 53:1272-1284, 2002Google Scholar

7. Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake, RE: Community-based treatment of schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders: treatment. MedGenMed 3(1), 2001 [formerly published in Medscape Psychiatry and Mental Health eJournal 6(1), 2001]. Available at www.medscape.com/viewarticle/430529Google Scholar

8. Mojtabai R, Nicholson RA, Carpenter BN: Role of psychosocial treatments in management of schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review of controlled outcome studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:569-587, 1998Google Scholar

9. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al: Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychological Medicine 32:763-782, 2002Google Scholar

10. Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, et al: Implementing evidence-based practice in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services 52:179-182, 2001Google Scholar

11. Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:45-50, 2001Google Scholar

12. Tarrier N, Haddock G, Barrowclough C: Training and dissemination: research to practice in innovative psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia, in Outcomes and Innovations in the Psychological Management of Schizophrenia. Edited by Wykes T, Tarrier N, Lewis S. New York, Wiley, 1998Google Scholar

13. Weiden PJ, McCrary KJ, Scheifler PL, et al: Team Solutions. Indianapolis, Ind, Eli Lilly and Company. Available at www.treatmentteam.com, 1997Google Scholar

14. Kim E, Vreeland B, Minsky S, et al: A Novel Method of Disseminating Psychosocial Treatment: A Preliminary Report. Presented at the Institute on Psychiatric Services, Boston, Oct 9-13, 2002Google Scholar

15. Pratt CW, Gill KJ, Barrett NM, et al: Psychiatric Rehabilitation. San Diego, Calif, Academic Press, 1999Google Scholar

16. Ascher-Svanum H: Development and validation of a measure of patients' knowledge about schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 50:561-563, 1999Google Scholar

17. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261-276, 1987Google Scholar

18. CGI: Clinical global impressions, in ECDEU Assessment for Psychopharmacology. Edited by Guy W. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976Google Scholar

19. Goldman HH, Skodol AD, Lave TR: Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1148-1156, 1992Google Scholar

20. Dupuy HJ: The Psychological General Well-Being (PGWB) Index, in Assessment of Quality of Life: Clinical Trials of Cardiovascular Therapies. Edited by Wenger NK, Mattson, ME, Furberg CD, et al. New York, Le Jacq, 1984Google Scholar

21. Jones SH, Thornicroft G, Dunn G, et al: A brief mental health outcome scale: reliability and validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). British Journal of Psychiatry 166:654-659, 1995Google Scholar

22. Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen N, et al: Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:826-836, 1995Google Scholar

23. Borkin JR, Steffen JJ, Ensfield LB, et al: Recovery Attitudes Questionnaire: development and evaluation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:95-102, 2000Google Scholar

24. Weiden P, Rapkin B, Mott T, et al: Rating of Medication Influences (ROMI) Scale in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:297-310, 1994Google Scholar

25. Arns P, Rogers ES, Cook J, et al: The IAPSRS Toolkit: development, utility, and relation to other performance measurement systems. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 25:43-52, 2001Google Scholar

26. Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH: Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:310-317, 2004Google Scholar

27. Dickerson F, Boronow JJ, Ringerl T, et al: Social functioning and neurocognitive deficits in outpatients with schizophrenia: a 2-year followup. Schizophrenia Research 37:13-20, 1999Google Scholar

28. Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, et al: Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1653-1664, 2002Google Scholar