Linking Inpatients With Schizophrenia to Outpatient Care

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study focused on inpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were scheduled to begin outpatient care with clinicians who had not previously treated them. The authors evaluated the effects of communication between the patients and their outpatient clinicians before discharge on patients' referral compliance, psychiatric symptoms, and community function at follow-up three months after discharge. METHODS: A total of 104 adult inpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were scheduled to receive outpatient care from clinicians who had not previously treated them were evaluated at hospital discharge and again three months later. Comparisons were made between patients who had telephone or face-to-face contact with an outpatient clinician before hospital discharge and patients who did not have such contact. RESULTS: About half (51 percent) of the inpatient sample communicated with an outpatient clinician before leaving the hospital. Compared with patients who had no communication, those who spoke with an outpatient clinician were significantly more likely to complete the outpatient referral. After baseline scores and other covariates were controlled for, predischarge contact with an outpatient clinician was associated with a significantly lower total Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale score at follow-up and less self-assessed difficulty controlling symptoms. Nonsignificant trends toward improved medication compliance and a lower rate of homelessness were also found. The two patient groups did not significantly differ in the proportion who were readmitted to the hospital or who made a psychiatric emergency room visit during the follow-up period. CONCLUSIONS: Direct communication between inpatients and new outpatient clinicians may help smooth the transition to outpatient care and thereby contribute to improved control of clinical symptoms.

Patients with schizophrenia commonly fail to continue in treatment after hospital discharge. As many as one-third to one-half of hospitalized patients with schizophrenia and related disorders miss their first scheduled outpatient appointment after hospital discharge (1,2,3). A failure to follow up with outpatient care after leaving the hospital greatly increases the risk of relapse and rehospitalization (4,5).

A number of discharge planning strategies have been developed to help smooth the transition from inpatient to outpatient care. Examples include scheduling appointments before hospital discharge (5,6), minimizing the period of time between discharge and the first scheduled outpatient appointment (7,8), providing telephone reminders and transportation to outpatient appointments (9,10), and, whenever possible, referring patients back to the same clinician who treated them before the hospitalization (11).

In some cases, it is not possible to refer inpatients back to the outpatient clinicians who have previously treated them. Patients move, refuse to return to their previous outpatient clinicians, or are referred to a level of care, such as day hospital treatment, that is different from what they received before the hospital admission. Under such circumstances, the risks of referral noncompliance are believed to be particularly great. One strategy for facilitating the referral is to arrange for the inpatient to meet the new outpatient clinician before the patient is discharged from the hospital (11). This meeting may help prepare the patient for the transition by reducing the patient's apprehension about the first scheduled outpatient appointment.

Social anxiety is common in schizophrenia (12). Fear of ordinary social situations may contribute to the common tendency among people with schizophrenia to social isolation (13). Longitudinal research has revealed that adults with schizophrenia commonly fail to establish close relationships, seldom initiate new social connections, and tend to withdraw from existing relationships (14,15). The general tendency of patients with schizophrenia to retreat from new social interactions strengthens the clinical rationale for introducing inpatients with schizophrenia to their outpatient clinicians before hospital discharge.

In the study reported here, we examined the effects of predischarge communication between outpatient clinicians and inpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder on patients' referral compliance, psychiatric symptoms, and functional outcomes. We compared the three-month posthospital adjustment of patients who received telephone or face-to-face contact with an outpatient clinician before discharge with that of a similar patient group who did not receive such contact. We hypothesized that as a consequence of predischarge contact with an outpatient clinician, patients would be more likely to complete referrals for outpatient care. We further predicted that as a consequence of improved linkage to outpatient care, predischarge communication with an outpatient clinician would be associated with improved symptom control and improved community functioning.

Methods

Data were drawn from the longitudinal patient outcome phase of the Rutgers hospital and community survey, which has been described in detail elsewhere (16). Briefly, a primary aim of the Rutgers study, conducted between 1991 and 1996, was to examine the relationship between psychiatric care in general hospitals and patient outcomes for Medicaid patients with schizophrenia and related disorders.

Subjects

Eligible subjects were English-speaking, newly admitted psychiatric inpatients, between 18 and 64 years old, who were Medicaid enrolled or eligible and had an admitting clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Subjects were subsequently entered in the study if they provided written informed consent and met criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (17), updated to include DSM-IV criteria, as administered by a trained research assistant. Patients with a severe and highly disabling general medical condition were ineligible for the study. Subjects who had stays longer than 120 days, who were discharged against medical advice, or who were transferred to another inpatient psychiatric facility were also excluded from the study.

Subjects were recruited in several phases. A total of 1,328 prescreened patients consecutively admitted to four general hospitals in New York City during the period from October 1994 to April 1996 met the age, payer status, and diagnosis eligibility criteria. Based on medical records and discussions with inpatient staff, we eliminated 4 percent of the screened sample due to severe general medical conditions, 4 percent who lived outside of New York City, and 9 percent who did not speak or understand English.

A total 1,010 screened patients (76 percent) were therefore assessed as eligible to receive the diagnostic interview. Of this group, 57 percent (N=576) agreed to be interviewed, 31 percent (N=310) refused, and 12 percent (N=124) were not approached. Of the 576 patients who consented to the diagnostic interview, 68 percent (N=394) met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Of the patients who met the diagnostic criteria, 71 did not complete the baseline assessment because they left the hospital against medical advice, were transferred to another inpatient facility, had a stay longer than 120 days, or withdrew their consent. The baseline inpatient assessment was administered to 323 patients and was completed by 316 patients.

The sample of 316 screened and selected patients and the 694 screened but nonselected patients did not significantly differ in age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, or recent work history. In addition, a similar proportion of the selected and nonselected samples reported active drug or alcohol use before admission (42 percent versus 38 percent for drug use and 38 percent versus 39 percent for alcohol use). However, blacks were overrepresented in the selected sample (58 percent versus 42 percent in the nonselected sample), and whites and Asians were underrepresented (whites, 40 percent versus 49 percent in the nonselected sample; Asians, 2 percent versus 9 percent in the nonselected sample) (χ2 =34.7, df=2, p<.001). Patients in the selected sample were also significantly more likely than those in the nonselected group to report at least one previous psychiatric hospitalization (93 percent versus 86 percent; χ2 =10.9, df=1, p<.01).

Of the 316 patients who entered the study, 117 were scheduled to begin outpatient care with a clinician who had not previously treated them. We located 104 of those patients (88.9 percent) for a three-month follow-up assessment. The group who was lost to follow-up did not significantly differ from the completer group in age, gender, race, or score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (18) or Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (19) at the baseline interview.

Assessments

Within 72 hours before hospital discharge, patients completed a structured assessment intended to collect data on clinical symptoms, social functioning, medication compliance, mental health service utilization, and other outcome domains. Clinical symptoms were assessed by trained research assistants using the BPRS, GAS, and the Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D) (20). Life satisfaction was assessed with items from the Quality of Life Interview (21). In addition, several self-report items were modified from the National Health Interview Mental Health Supplement to assess difficulties with psychosocial functioning (22).

Three months after hospital discharge, patients were reinterviewed by trained research assistants using the same clinical instruments. At the time of discharge, each patient's primary inpatient clinician was asked to complete an Inpatient Treatment Survey, which was developed to probe various aspects of inpatient service delivery. Clinicians were asked whether the patient was scheduled to begin treatment with a new outpatient clinician after hospital discharge. Other items ascertained whether an outpatient clinician came to the unit to evaluate the patient, whether an outpatient clinician talked to the patient by telephone, or whether the patient went for an interview or started the outpatient program while still in the hospital. In the analyses described below, patients who were scheduled to see a new clinician were stratified by whether they received at least one of these three services, which we collectively refer to as contact with an outpatient clinician before hospital discharge.

Analytic strategy and statistical methods

Our primary goal was to study the effect of predischarge outpatient clinician contact on the short-term course of patients with schizophrenia. The two study groups were first compared on sociodemographic characteristics, hospitalization history, length of index inpatient stay, and presence of DSM-III-R drug or alcohol use disorders as determined by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (23). Student's t test was used for comparisons involving continuous variables, and the chi square test was used for comparisons involving categorical variables. Comparisons were considered statistically significant at the 5 percent level (alpha=.05, two-tailed).

We also compared the patients with and without outpatient contact before discharge on aspects of inpatient treatment, including legal status, satisfaction with treatment, and perceived likelihood of continuing in outpatient care. The two groups' experience during the three-month follow-up period was then compared, including the proportions of each group who completed scheduled outpatient referrals, made a psychiatric emergency room visit, were hospitalized, became homeless, or reported a period of one week or more of complete cessation of their antipsychotic medications. Separate analyses were made of the proportion of patients in each group who reported increased difficulties from the baseline to the follow-up assessment in four areas of psychosocial functioning and symptom scores at three months after discharge. Multiple linear regression equations were used to examine associations between predischarge outpatient clinician contact and symptom scores at follow-up, controlling for age, gender, race, hospital, legal status of admission, and baseline symptom scores. Selected comparisons involving patients who were scheduled to return to the outpatient clinicians who had previously treated them are also presented.

Results

General characteristics

Approximately half of the inpatients who were referred to new outpatient clinicians (53 patients, or 51 percent) communicated with them before hospital discharge. Most of these patients (43, or 81.1 percent) went for an interview at an outpatient program while they were still in the hospital. The remainder either spoke with an outpatient clinician on the telephone (five patients, or 9.4 percent), met an outpatient clinician on the inpatient unit (three patients, or 5.7 percent), or both (two patients, or 3.8 percent).

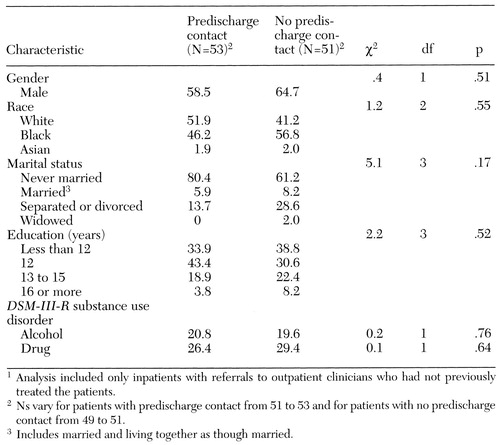

The two study groups did not differ in their racial or gender distribution. The mean±SD age of the groups was 33.4±8.7 years for patients with predischarge contact with outpatient clinicians and 34.4±9.9 years for patients with no contact, not a significant difference. A majority of patients in each group had never married and had a relatively low level of education (see Table 1). Substantial and similar proportions of each group met criteria for a DSM-III-R alcohol or drug use disorder at the time of hospital discharge.

Inpatient treatment

The proportion of inpatients who had contact with an outpatient clinician before discharge varied across the four participating hospitals (χ2 =20.8, df=3, p<.001). At three of the hospitals, a majority of the patients (ranging from 60.2 percent to 65.2 percent) had predischarge outpatient clinician contact. However, at one hospital only two of 22 patients (9.1 percent) had such contact.

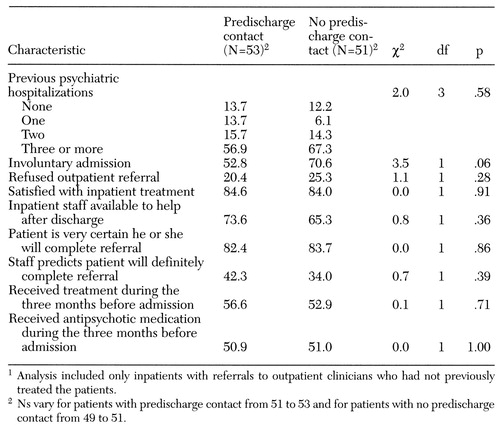

Most of the patients in both study groups had three or more previous psychiatric hospitalizations (see Table 2). In addition, a majority in each group viewed their inpatient care as satisfactory and believed that if they needed help after hospital discharge, there was a staff member on the unit whom they could contact. A similar proportion of both groups refused one or more outpatient referrals during the course of their inpatient stay.

Although a majority in each group were admitted involuntary to the hospital, there was a nonsignificant trend toward involuntary admission among patients who did not have contact with an outpatient clinician before hospital discharge (see Table 2). The two groups did not significantly differ in mean length of inpatient stay (40±24.9 days for patients with predischarge contact with their outpatient clinicians and 34.5±22 days for patients without such contact).

The vast majority of the inpatients with and without predischarge outpatient clinician contact were very certain that they would keep their scheduled outpatient appointments (see Table 2). In this regard, inpatient staff were considerably less optimistic. The staff predicted that only a minority of the patients in each group would definitely attend the arranged outpatient mental health programs.

Service utilization outcomes

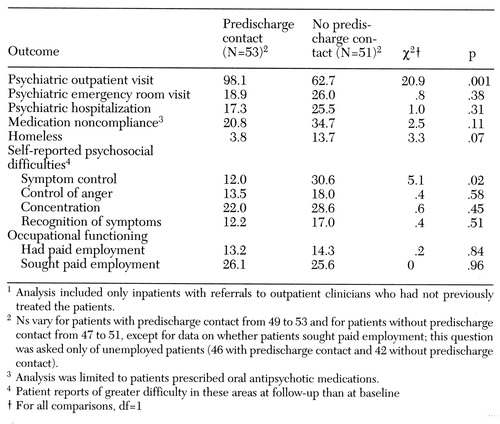

As Table 3 shows, patients who communicated with an outpatient clinician before discharge were significantly more likely than those who did not communicate to complete their scheduled referral for outpatient care. Remarkably, only one patient who met or spoke with an outpatient clinician before leaving the hospital failed to complete the scheduled outpatient referral.

The two study groups did not significantly differ in the proportion who made a psychiatric emergency room visit, required readmission to a psychiatric hospital, or reported a period of medication noncompliance of one week or more during the three-month follow-up period (see Table 3). However, there was a nonsignificant trend toward an increased rate of self-reported medication noncompliance among the patients who did not have predischarge contact with an outpatient clinician.

Psychiatric symptoms

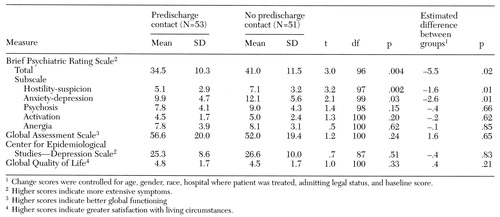

At follow-up, the group who had predischarge contact with an outpatient clinician had a significantly lower mean total BPRS score than the group with no contact. After the follow-up BPRS score was adjusted for age, gender, race, hospital, admitting legal status, and baseline BPRS score, outpatient clinician contact was associated with a 5.5 point decrease in total BPRS score (see Table 4). An analysis using BPRS subscale scores (24) revealed that outpatient clinician contact was associated with a significant decrease in the hostility-suspicion and anxiety-depression subscale scores. In a separate model, completion of the outpatient referral was associated with a lower total BPRS score at follow-up after baseline BPRS score, age, gender, and race were controlled for (beta=-6, p=.04). Because only one patient met with an outpatient clinician before hospital discharge but did not receive outpatient care, we could not explore the interaction between inpatient contact with outpatient clinicians, referral compliance, and symptom control.

Inpatients with no predischarge contact reported more psychosocial difficulties in several areas. In the area of symptom control, this difference reached the level of statistical significance (see Table 3). The two study groups did not significantly differ in mean scores on the GAS or CES-D or global QLI scores at follow-up (see Table 4).

Other outcomes

As Table 3 shows, there was a nonsignificant trend toward reduced homelessness among patients who communicated with an outpatient clinician before hospital discharge. This trend became statistically significant when the sample was expanded to include patients who were scheduled to return to clinicians who had previously treated them (5.4 percent versus 15 percent, χ2 =6.4, df=1, p= .01). At the follow-up interview, a similar proportion of patients in each group reported having worked for pay or having sought paid employment.

Inpatients returning to outpatient clinicians

The study also provided follow-up data on 135 patients scheduled to return to outpatient clinicians who had previously treated them. Within this patient group as well, predischarge contact with an outpatient clinician was associated with successful completion of the outpatient referral. Of the 68 patients who had predischarge contact with an outpatient clinician, 62, or 91.2 percent, completed their referral, compared with 49 of the 67 patients, or 73.1 percent, who did not have such contact (χ2 =7.5, df=1, p=.006).

Compared with the 104 patients starting with new clinicians, the 135 returning patients were significantly more likely to have had a previous inpatient psychiatric admission (96.3 percent versus 87.5 percent; χ2 =6.5, df=1, p=.01) and to have taken antipsychotic medications during the three months before the index admission (80.7 percent versus 51 percent; χ2 =23.9, df=1, p<.001). Patients who had no previous psychiatric admissions improved from baseline to follow-up in mean BPRS score significantly more than those who had previous admissions (t=2.1, df=236, p=.04). Similarly, patients who were not taking antipsychotic medications before admission improved more than patients who were on medications before admission (t=1.9, df=235, p=.05).

In a correlation that controlled for baseline BPRS score, discharge to a new clinician was correlated with a significant improvement in BPRS score (beta=-4.1, p=.007). However, this relationship was attenuated when the correlation was first controlled for whether the patient was taking medication before the index admission (beta=-3.8, p=.02) and then by whether the patient had been previously hospitalized (beta=-3.4, p=.04).

Discussion and conclusions

We found that inpatients with schizophrenia who communicated with their new outpatient clinicians before they left the hospital were substantially more likely to complete their referrals for outpatient care compared with inpatients who did not have such contact. The inpatients who met or spoke with a new outpatient clinician were also less symptomatic at follow-up, and fewer of them reported difficulties controlling their symptoms, presumably because they were more likely to continue in outpatient care. These findings are consistent with earlier research on the value of coordinating the referral process (2,5,11,25) and underscore the importance of the interpersonal dimension of the referral process.

Introducing severely mentally ill inpatients to new outpatient clinicians while they have the support of inpatient staff may ease patients' anxieties over meeting the clinician for the first time. If the first contact between the outpatient clinician and the inpatient is successful, it may form a basis for developing a working alliance. Patients with schizophrenia who form strong alliances with their outpatient clinicians during the first few months of treatment have been found to achieve superior outcomes (26).

Inpatients who start with new outpatient clinicians are likely to be earlier in their illness trajectories and less compliant with treatment processes than are patients who are returning to clinicians who have previously treated them. Because patients referred to new clinicians are less likely to have been on medication than continuing patients, becoming involved in active treatment may be especially helpful in promoting symptom improvement.

It is possible that inpatients who have greater interest in or motivation for participating in their own recovery are particularly amenable to meeting their new outpatient therapist. In other words, inpatient communication with a new outpatient clinician may serve as a proxy for treatment motivation, and it may be this motivation rather than the meeting per se that explains the improved outcomes. However, we found no evidence that the inpatients who communicated with an outpatient clinician were more favorably predisposed to treatment than the inpatients who did not. For example, a similar proportion of each group refused an outpatient referral or expressed dissatisfaction with their inpatient treatment. The association between predischarge outpatient clinician contact and improved symptoms also remained significant after the analysis controlled for legal status at admission, which is presumably related to treatment motivation. However, because the study was observational rather than experimental in design, we cannot rigorously exclude the possibility that differences in motivation or other unmeasured patient characteristics or treatments account for the observed outcomes.

Marked differences in the rate of outpatient clinician contact between the participating hospitals suggest that hospital treatment routines may play an important role in determining whether inpatients meet their new outpatient clinician before hospital discharge. At the hospital that only rarely established predischarge contact between inpatients and their new outpatient clinicians, we found little evidence during a site visit that the inpatient staff were actively involved in promoting continuity of care. Inpatient staff reported that they seldom made special efforts to ensure that more difficult-to-place patients were connected to appropriate outpatient services and expressed little interest in the patient's course of recovery after hospital discharge.

Surveys of inpatient staff have indicated that psychiatric inpatient units vary considerably in how they approach the inpatient treatment of schizophrenia, with some units placing a greater emphasis than others on practices likely to improve continuity of care (27). The findings reported here support strategies for strengthening treatment in this area by expanding the clinical responsibilities of inpatient staff and outpatient clinicians to include introducing selected severely ill inpatients to their outpatient clinician before hospital discharge. Such an added responsibility runs counter to the trend to shortening the length of inpatient stays (28) and narrowing the scope of inpatient treatment (29) and may therefore be difficult to implement in some inpatient settings.

Inpatients in the study reported here had relatively long inpatient stays. At many units, financial considerations have driven the average lengths of inpatient stay for patients with schizophrenia below two weeks (30). Shortening the length of hospitalization reduces the time available to stabilize patients and arrange for them to meet with an outpatient clinician. Some payers explicitly restrict payment for outpatient services for inpatients as a form of double billing. Such restrictive reimbursement policies further reduce the clinical opportunity to familiarize inpatients with outpatient care and may thereby impede continuity of care.

We did not find a significant effect of inpatient contact with outpatient clinicians on improved occupational functioning, quality of life, rehospitalization, or emergency room visits. However, we did find a nonsignificant trend toward reduced homelessness and a weak trend toward improved medication compliance. The relative independence of clinical symptoms from level of community functioning (31) may help explain our failure to find significant differences in functional outcomes despite improvements in clinical symptoms. It is also possible that a larger sample, followed with more sensitive measures over a longer time period, might have yielded different results.

Several other caveats should be noted. First, no information was available on the posthospital adjustment of the 13 patients referred to new clinicians who were lost to follow-up. Although this group resembled the completer sample in baseline psychopathology, we have no means of assessing the effects of predischarge communication with new outpatient clinicians among these patients. Second, as previously noted, the observational design of the study made it impossible to exclude effects of unmeasured treatment or patient variables that could have contributed to the observed outcomes. Third, the study sample represented a highly impaired inpatient population who were referred to outpatient clinicians who had not previously treated them, and the results may not generalize to other patient groups.

The period immediately after psychiatric hospital discharge is especially hazardous. During this time, patients are at increased risk for treatment dropout (25), clinical relapse (32), homelessness (33), and suicide (34). When inpatients with schizophrenia are referred to clinicians whom they do not know, the risks may be particularly great. Introducing inpatients to their outpatient clinician before patients leave the hospital may help improve their short-term clinical outcome.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and grants 43450 and 01042 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Olfson is associate professor in the department of psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons at New York State Psychiatric Institute, 722 West 168th Street, New York, New York 10032 (e-mail, [email protected]). He is also research associate at the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, where Dr. Mechanic is director and Dr. Boyer is associate director. Dr. Hansell is associate professor of sociology at Rutgers University.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of inpatients with schizophrenia who did and did not have predischarge contact with outpatient clinicians, in percentages1

|

Table 2. Treatment characteristics of inpatients with schizophrenia who did and did not have predischarge contact with outpatient clinicians, in percentages1

|

Table 3. Three-month postdischarge outcomes for service use and impairment among patients who did and did not have contact with outpatient clinicians while in the hospital, in percentages1

|

Table 4. Mean scores on measures of symptoms three months after discharge among patients who did and did not have contact with outpatient clinicians while in the hospital

1. Miner CR, Rosenthal RN, Hellerstein DJ, et al: Prediction of compliance with outpatient referral among inpatients with schizophrenia and psychoactive substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:706-712, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bogin DL, Anish SS, Taub HA, et al: The effects of a referral coordinator on compliance with psychiatric discharge plans. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:702-706, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

3. Solomon P, Davis J, Gordon B: Discharged state hospital patients' characteristics and use of aftercare: effect on community tenure. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:1566-1570, 1984Link, Google Scholar

4. Green JH: Frequent rehospitalization and noncompliance with treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:963-966, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Stickney SK, Hall RWC, Gardner ER: The effect of referral procedures on aftercare compliance. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 31:567-569, 1980Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Sullivan K, Bonovitz JS: Using predischarge appointments to improve continuity of care for high-risk patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 32:638-639, 1981Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Axelrod S, Wetzler S: Factors associated with better compliance with psychiatric aftercare. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:397-401, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn DA: The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 12B):1-58, 1996Google Scholar

9. McIntosh J, Worley N: Beyond discharge: telephone follow-up and aftercare. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 32:21-27, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bostelman S, Callan M, Rolincik LC, et al: A community project to encourage compliance with mental health treatment aftercare. Public Health Reports 109:153-157, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

11. Chen A: Noncompliance in community psychiatry: a review of clinical interventions. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:282-287, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Penn DL, Hope DA, Spaulding W, et al: Social anxiety in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 11:277-284, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Strauss JS, Rakfeldt J, Harding CM, et al: Psychological and social aspects of negative symptoms. British Journal of Psychiatry 155(suppl):128-132, 1989Google Scholar

14. Isele R, Merz J, Malzacher M, et al: Social disability in schizophrenia: the controlled prospective Burghölzi study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 234:348-356, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hamilton NG, Ponzoha CA, Cutler DL, et al: Social networks and negative versus positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 15:625-633, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Boyer CA, Olfson M, Kellermann SL, et al: Studying inpatient treatment practices in schizophrenia: an integrated methodology. Psychiatric Quarterly 66:293-320, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Edition (SCID-P, Version 1.0). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1990Google Scholar

18. Overall JE, Gorham DP: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-807, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766-771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385-401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Lehman AL: A Quality of Life Interview for the Chronically Mentally Ill—Shortened Version. Baltimore, University of Maryland, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 1992Google Scholar

22. Mental Health, United States, 1992. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA. DHHS Pub (SMA) 92-1942. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1992Google Scholar

23. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al: Comparison of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview with the SCID-P and CIDI: a validity study. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 31:616, 1995Google Scholar

24. Guy W: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, rev ed. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976Google Scholar

25. Caton C, Koh S, Fleiss JL, et al: Rehospitalization in chronic schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 173:139-148, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Frank AF, Gunderson JG: The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of schizophrenia: relationship to course and outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:228-236, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Olfson M, Boyer CA, Hansell S, et al: Toward an integrated approach to the study of inpatient treatment of schizophrenia. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 73:25-38, 1997Google Scholar

28. Wickizer TM, Lessler D, Travis KM: Controlling inpatient psychiatric utilization through managed care. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:339-345, 1996Link, Google Scholar

29. Persad E, Kazarian SS, Joseph LW: The Mental Hospital in the 21st Century. Middletown, Ohio, Wall & Emerson, 1992Google Scholar

30. Olfson M, Mechanic D: Mental disorders in public, private nonprofit, and proprietary general hospitals. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1613-1619, 1996Link, Google Scholar

31. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of the neurocognitive deficits of schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry 253:321-330, 1996Google Scholar

32. Caton CLM, Goldstein JM, Serrano O, et al: The impact of discharge planning on chronic schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:255-262, 1984Abstract, Google Scholar

33. Caton CLM: Mental health service use among homeless and never-homeless men with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 46:1139-1143, 1995Link, Google Scholar

34. Geddes JR, Jusczak E: Period trends in rate of suicide in the first 28 days after discharge from psychiatric hospital in Scotland, 1968-92. British Medical Journal 311:357-360, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar