Effects of Psychoeducational Intervention for Married Patients with Bipolar Disorder and Their Spouses

Abstract

The relative benefit of adding a structured psychoeducational intervention to standard medication treatment for married patients with bipolar disorder and their spouses was assessed. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either medication management or medication management plus a marital intervention with their spouses for an 11-month period. Patients' symptoms, functioning, and adherence to their medication regimens were measured at study entry and at 11 months. Significant effects favoring the combined treatments were observed for overall patient functioning but not for symptom levels. The marital intervention was associated with improved medication adherence. Combined psychosocial and medication treatment does not affect patients' symptom levels beyond the effects of medication alone, but it does result in significant incremental gains in overall patient functioning.

Pharmacological treatments for patients with bipolar disorder have been proven effective, but several factors suggest that medication alone may not be sufficient for at least a subgroup of patients. Medication compliance is often variable, and medications may have limited impact on impaired social functioning.

To our knowledge, no controlled studies of combined medication and psychosocial treatment of patients with bipolar disorder and their spouses have been reported. Data from our previous work indicate that a combination of inpatient psychosocial and pharmacological treatments can result in improved work and social functioning for patients with bipolar disorder (1–3). This study replicates and extends our findings on the effects of psychoeducational intervention for patients with bipolar disorder.

Methods

Patients consecutively admitted to inpatient and outpatient services were considered for inclusion in the study on the basis of the following criteria: age 21 to 65 years; an admission diagnosis of major affective disorder or bipolar disorder, manic, depressed, or mixed, based on an interview using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS); and a marital status of married or living with a significant other of the opposite sex for at least six months. Exclusionary criteria included the presence of organic brain syndrome, a current primary diagnosis of alcohol or drug abuse, pregnancy, and a significant medical history contraindicating the use of lithium or carbamazepine.

Patients were assigned to an experimental group or a control group using a randomizing algorithm that took into account number of prior admissions, history of prehospital treatment compliance, and level of functioning at admission into the study. All patients in both groups received standardized medication in each of three classes: mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and antipsychotics. Patients in the experimental group also received 25 sessions of marital intervention. Social workers with three to five years of experience in family treatment conducted the marital intervention as described in the treatment manual. (A copy of the manual is available at cost from the first author.)

Couples in the experimental group received 25 marital sessions at a usual rate of one session a week for the first ten sessions, then bimonthly for the remaining 15 sessions. Thus the family intervention extended over approximately 11 months. We sampled audio tapes of marital intervention sessions and found that the social workers conducting the intervention adhered to the procedures outlined in the treatment manual.

We developed a 5-point system for rating the severity of bipolar disorder based on data for two years before the patient's entry into the study. The data were collected in interviews using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Lifetime Version. Interrater reliability for the rating was adequate (kappa=.78 for two raters).

Patients' symptoms, functioning, and adherence to their medication regimen were assessed at study entry and at 11-month follow-up. Symptoms were assessed using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Change Version (SADS-C), which measures symptoms within the past week, and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Functioning was assessed using the Social Adjustment Scale and the Global Assessment Scale. Medication adherence was rated on a scale from 1, poor, to 6, excellent, that was developed in our previous work (4).

Results

Of 46 patients who signed informed consent forms, four dropped out. Nineteen patients were randomly assigned to receive both medication and the psychoeducational marital intervention, and 23 to receive medication only. The gender distribution of the patients was almost equal—25 patients were male, and 21 were female. Patients' average age was 47.7 years. The mean±SD number of medication visits for the entire sample was 32±12.58. We had complete data through 11 months of treatment for 33 patients, 18 who received the psychoeducational marital intervention and 15 who received medication management only. The results we report are for this sample.

Medication adherence was rated as quite good in both groups, but the mean level of medication adherence in the experimental group was significantly higher than that in the control group (5.70 versus 5.17, t=2.84, df=38, p=.008).

We attempted to model differences in patients' symptoms, measured using the SADS-C, and functioning, measured using the GAS, across time and treatment condition. The SADS-C showed some degree of positive skew, while the GAS was somewhat negatively skewed. We tried several different transformations and were able to significantly improve the degree of normality in the GAS distribution with a square transformation. None of the transformations that we considered improved the distribution of the SADS-C.

In all of our subsequent model fitting, we used the untransformed version of the SADS-C and the squared version of the GAS as our dependent measures. We began by fitting a model that predicted symptoms based on time, group, and the time-group interaction. To evaluate the contribution of each predictor, we compared this saturated model with a model that did not include the predictor of interest, using the likelihood ratio test. We did separate model fitting for symptoms (SADS-C) and patient functioning (GAS). All models were two-staged mixed-effect models, which allowed each subject to have his or her own profile of change on the dependent measure. Group membership was treated as a fixed effect, with time and the time-group interaction treated as random effects. Model fitting was done using the LME module of S-Plus, following the overall approach described by Davidian and Giltinan (5).

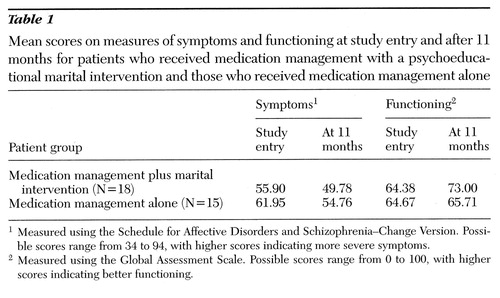

The time-group interaction did not contribute significantly to the model of symptoms. Both the group and the time effects were significant (likelihood ratio=5.71, p<.02, and 9.43, p<.03, respectively). In the model describing change in patient functioning over time, the interaction term was significant (likelihood ratio=9.43, p<.03), indicating that patients in the experimental group showed greater improvement in overall functioning. The mean scores for both treatment groups for symptoms and functioning are shown in Table 1. Because patients were assigned to treatment condition taking into account several variables, the two groups differed somewhat in symptoms at admission to the study.

Discussion and conclusions

Patients receiving the psychoeducational marital intervention showed significant improvement in overall functioning but not in symptoms. Medication compliance was also significantly better among patients receiving the psychoeducational intervention. However, some limitations of the study are important to note. The total sample was small, and the power was compromised. The sample was composed of patients with bipolar disorder and their spouses who were middle aged and had been married for an average of 17 years. It may be that an aggressive combined treatment earlier in both the disorder and the marital relationship would have had more impact.

Because patients in the experimental group spent more time with the treatment team than did the medication-only group, the effects may be due to amount of time rather than to the psychosocial treatment. However, medication adherence did increase among patients receiving the psychoeducational marital intervention, a specific effect, and functioning responded more than symptoms, as would be expected of a combined treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01-MH45528-OIA3 to Dr. Clarkin from the National Institute of Mental Health and by a fund established in the New York Trust by DeWitt Wallace.

Dr. Clarkin is professor of clinical psychology in psychiatry at Cornell University Medical College and director of psychology at the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, Westchester Division, 21 Bloomingdale Road, White Plains, New York 10605 (e-mail, JClarkin%WestNYH @NYH.Med.Cornell.edu). Dr. Carpenter is director of clinical data services at Merit Behavioral Care Corporation in Park Ridge, New Jersey. Dr. Hull is associate professor of clinical psychology in psychiatry at Cornell University Medical College and staff psychologist at the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, Westchester Division. Dr. Wilner is associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Cornell University Medical College and attending psychiatrist at the Payne Whitney Clinic in New York City. Dr. Glick is professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California.

|

Table 1. Mean scores on measures of symptoms and functioning at study entry and after 11 months for patients who received medication management with a psychoeducational marital intervention and those who received medication management alone

1Measured using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Change Version. Possible scores range from 34 to 94, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.

2Measured using the Global Assessment Scale. Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning.

1. Clarkin JF, Haas GL, Glick ID: Inpatient family intervention, in Affective Disorders and the Family: Assessment and Treatment. Edited by Clarkin JF, Haas GL, Glick ID. New York, Guilford, 1988Google Scholar

2. Clarkin JF, Haas GL, Glick ID (eds): Affective Disorders and the Family: Assessment and Treatment. New York, Guilford, 1988Google Scholar

3. Clarkin JF, Glick, ID, Haas GL, et al: A randomized clinical trial of inpatient family intervention: V. results for affective disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders 18:17-28, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Glick ID, Clarkin JF, Spencer JH, et al: A controlled evaluation of inpatient intervention:1. preliminary results of the six-month follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:882-886, 1985Google Scholar

5. Davidian M, Giltinan D: Nonlinear Models for Repeated Measurement Data. London, Chapman & Hall, 1995Google Scholar