Psychotherapy, Symptom Outcomes, and Role Functioning Over One Year Among Patients With Bipolar Disorder

There is mounting evidence that individual, family, and group psychosocial interventions, when combined with standard pharmacotherapy, delay relapses and enhance the symptomatic outcome of bipolar disorder ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). Research on adjunctive psychosocial interventions is based primarily on randomized trials, with carefully selected samples, manual-based psychosocial protocols, and predetermined durations and frequencies of treatment. Although these design features strengthen the internal validity of the trials, they also raise the question of whether psychotherapy as practiced in the community has similar effects on the course of bipolar illness when samples are broadly characterized, psychotherapy methods and intensities vary, and patients elect to receive psychotherapy rather than being randomly assigned to it. No studies have explored the effects of psychosocial interventions on community samples of patients with bipolar disorder followed naturalistically.

This study examined whether patients with bipolar disorder who receive regular adjunctive psychosocial intervention in community settings have a lower symptom burden during or after treatment than patients who receive little or no psychosocial intervention. Participants were patients in a depressive phase of bipolar disorder drawn from the first 1,000 enrollees in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) ( 10 ), a multicenter research program concerning the nature, course, and long-term outcome of patients with bipolar disorder receiving best-practice pharmacotherapy. Because of its naturalistic design, STEP-BD afforded an opportunity to examine the association between psychotherapy use and outcome among patients who select it because they desire the additional treatment, have the financial means to obtain it, and have access to therapists.

An initial cross-sectional study of the first 500 patients in the STEP-BD indicated considerable variability in use of psychotherapy ( 11 ). In the three months before entering STEP-BD, 54 percent of the eligible patients obtained some form of psychotherapy in addition to medications. Patients who received adjunctive psychotherapy had lower global functioning scores, were less likely to be married, and had greater rates of comorbid disorders than those who did not receive services. This initial study, however, did not address the prospective association between psychotherapy and patients' longer-term symptomatic or functional outcomes.

Using a one-year prospective design, we examined several questions: How frequently did patients with bipolar depression use psychotherapy services during their first year in STEP-BD, and with what kinds of providers? What patient variables were associated with the amount of service use? Did the amount of psychotherapy that patients received in any given study interval predict their concurrent or subsequent levels of depressive or manic symptoms or role functioning once their preinterval levels of symptoms or role functioning were covaried? Was the association between psychotherapy and clinical outcome different for patients who were more severely ill?

Methods

Participants

Individuals with bipolar disorder were drawn from the first 1,000 enrollees in the naturalistic "Standard Care" study of STEP-BD between November 1999 and April 2002 ( 12 ). To qualify for STEP-BD, patients had to be at least 15 years of age and meet DSM-IV ( 13 ) criteria for bipolar I or II disorder or a bipolar spectrum disorder (defined below). Patients were excluded if they were unwilling or unable to provide informed consent or did not speak English.

All 16 study sites received approval to implement STEP-BD from their respective institutional review boards. All principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed. Research staff members fully explained the study protocol to potential participants before obtaining written informed consent ( 10 ).

Of the first 1,000 patients, 248 (25 percent) entered STEP-BD in a DSM-IV major depressive episode. The number of patients who entered STEP-BD in states of DSM-IV mania, 51, was too small to warrant separate examination. The mean±SD age of the 248 participants with bipolar disorder, depressed phase was 41.1±12.3 years; 137 (58 percent) were women. Participants were predominantly Caucasian (93 percent), and most (95 percent) had graduated from high school. The most common diagnosis was bipolar I disorder (N=166, or 67 percent), followed by bipolar II disorder (N=67, or 27 percent); bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (N=12, or 5 percent); schizoaffective disorder, bipolar subtype (N=2, or 1 percent); or cyclothymic disorder (N=1, which was less than 1 percent). The age at illness onset was 16.6±8.4 years.

Diagnostic evaluation

To validate the bipolar diagnosis at study entry, project clinicians administered the Affective Disorders Evaluation, a semistructured interview adapted from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Patient Version ( 14 , 15 ). Separate clinicians interviewed patients on a different occasion using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI Plus, version 5.0) ( 16 ). Study diagnoses were assigned once there was consensus between the two interviews.

Longitudinal follow-up

Patients were seen in university- or community-based outpatient clinics, depending on the site. Psychiatrists treated patients using standardized pharmacological guidelines for bipolar disorder ( 17 ). Independent evaluators conducted structured interviews with patients on a quarterly basis for one year (baseline and at three, six, nine, and 12 months), during which they completed service use, role functioning, and symptom severity measures. The instruments for measuring mood symptoms were the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) ( 18 ) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) ( 19 ), which yielded estimates of the severity of symptoms in the final week of each three-month study interval. Scores for each range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.

Functional outcomes were measured every three months with the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-Range of Impaired Function Tool (LIFE-RIFT) ( 20 , 21 ) covering the final week of each interval. The LIFE-RIFT is a clinician-rated scale that assigns scores from 1, indicating no impairment, to 5, indicating severe impairment, in each of four areas of functioning—work and role performance, interpersonal relationships, recreation, and satisfaction with activities. Overall role function scores range from 4, indicating good functioning, to 20, indicating poor functioning.

Psychosocial service use

The measure of psychotherapy use was the interview-based Care Utilization Form ( 10 ), which was administered every quarter and covered the prior three-month interval. We narrowed our definition of psychotherapy services to the number of patient contacts during each interval with professionally trained therapists—psychologists, social workers, mental health counselors, or psychiatric nurses—for assistance with emotional problems. We did not include contacts with psychiatrists in these computations because psychiatric sessions within STEP-BD emphasized pharmacological management. Although supportive psychotherapy may have been offered during these visits as well, the amount provided was not standardized or measured within the STEP-BD protocol.

Statistical analyses

We reasoned that patients who developed symptoms during the course of STEP-BD treatment would seek out or be offered more psychotherapy services. Thus the symptomatic or functional state of patients in the three-month interval before obtaining services needed to be statistically covaried when we examined the association between psychotherapy and symptom outcomes. Second, we reasoned that psychotherapy could be associated with symptomatic or functional outcomes during the same interval in which it was delivered, or it could be associated with future outcomes.

When plotting service use (number of sessions received) at each of the four follow-up intervals (months 1-3, 4-6, 7-9, and 10-12), we determined that the distributions were positively skewed and that natural breaks occurred between patients who received no adjunctive psychotherapy sessions, between one and three sessions, between four and 12 sessions, and more than 12 sessions. Accordingly, we conceptualized service use as a four-level categorical variable.

With data from each quarterly interval, we used mixed-effects regression models ( 22 ) to examine how baseline symptoms (MADRS or YMRS scores measured at the end of the prior interval) and psychotherapy during the interval were related to depression, mania, or role functioning scores during the same or a subsequent interval. The regression models, which were conducted with the PROC MIXED program in the SAS statistical package ( 23 ), enabled us to consider multiple quarterly follow-up intervals simultaneously rather than constructing separate models for each interval. Unlike standard repeated-measures analyses of variance, mixed-effects models with random subjects effects permit the analysis of repeated measurements over time while controlling for the within-subject correlation of the dependent measure—MADRS scores, for example. These methods are valid under the assumption that data are missing at random. For a cogent discussion of the differences between mixed-effects regression models and repeated-measures analysis of variance, see Gueorguieva and Krystal ( 22 ).

For example, depression recorded at the nine-month assessment point (covering the prior week) was regressed on use of psychotherapy during months 7 through 9, on the level of depression recorded in the final week of interval 3 to 6, and on their statistical interaction. A separate lagged-effects model regressed depression, mania, or role functioning in interval x (for example, at nine months) on use of psychotherapy in the previous interval (months 3 through 6) and on depression in the final week of that interval (months 3 through 6).

Because female patients with depression are more likely to seek therapy than male patients ( 24 ), and because access to psychotherapy is likely to be influenced by household income, we covaried patients' sex and income in each regression model. The regression models were under-powered to examine interactions of treatment and site because of the large number of sites ( 16 ); thus we did not include site as a covariate.

Results

Patients' use of psychosocial services at follow-up

The mixed-effects regression models included observations from all participants with service use data, even from those who did not complete the full follow-up. Of the 248 patients in a depressive phase of bipolar disorder, data on use of psychotherapy were available during at least one quarterly follow-up interval for 179 (72 percent). A total of 107 of the 179 patients with service use data (60 percent) obtained at least one adjunctive psychotherapy session during the study year. The mean number of psychotherapy contacts for the full sample was 8.04±15.61 (range 0 to 97).

Table 1 summarizes the number of contacts that patients had with mental health professionals during each three-month interval. Visits to psychologists were the most common, followed by visits to social workers, counselors, and nurses.

|

Correlates of service use

We examined whether patients who received more therapy sessions per interval differed systematically from those who received fewer sessions. A mixed-effects regression model examined the following predictors of service use: age, sex, income, age at illness onset, marital status, bipolar I versus II subtype, comorbid personality disorder (based on the Affective Disorders Evaluation), past or current anxiety disorder (based on the MINI), past or current substance use disorder, and number of prior episodes of mania or depression. The dependent variables were the four-category psychotherapy use variables computed at three, six, nine, or 12 months, with all follow-up points considered simultaneously.

Patients with fewer than ten prior depressive episodes used more psychotherapy than patients with more than ten prior episodes (F=3.27, df=3, 110, p=.024). The association between marital status and service use approached but did not reach significance. No other variable predicted service use. To reduce the effects of selection biases in treatment seeking, we included the number of prior depressive episodes and marital status, along with patients' sex and income as covariates in the mixed-effects regression models.

Amount of service use and depression and mania symptoms

Concurrent associations. The first mixed-effects model examined predictors of depression severity. In this model, MADRS depression scores recorded in the final week of an interval (three, six, nine, or 12 months) were regressed on psychotherapy use in the same interval, with MADRS and YMRS scores recorded during the final week of the previous interval as predictor variables. Data from 146 patients in the sample were available for this analysis.

This model ( Figure 1 ) revealed no main effect of amount of therapy use on depression in the same study interval. Depression in the prior three-month interval predicted depression in the next interval (F=17.04, df=1, 138, p<.001), but YMRS scores from the prior interval did not. An interaction between depression in the prior interval and therapy usage in the current interval was significant (F=2.77, df=3, 138, p=.044). This interaction indicated that among patients who began the current interval with more severe depression symptoms (for example, MADRS scores of 33), receiving four or more psychotherapy sessions during the current interval was associated with lower depression scores by the end of the interval, whereas receiving three or fewer sessions was associated with higher MADRS scores by the end of the interval ( Figure 1 ). The interaction also indicated the reverse: among patients who began the current interval with mild depression (for example, MADRS=15), receiving 12 or fewer psychotherapy sessions was associated with lower MADRS scores at the end of the interval, whereas receiving more than 12 sessions was associated with higher MADRS scores. The patients' sex and history of depressive episodes were not associated with MADRS scores in the current interval, although independent associations of income (F= 5.18, df=2, 138, p=.007) and marital status (F=7.86, df=1, 138, p=.006) with MADRS scores were observed.

a A Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score of 15 (low depression) represents the lower 15th percentile of the sample, a score of 23 represents the 50th percentile, and a score of 33 represents the 85th percentile (high depression). MADRS scores in the prior three-month interval interacted with the amount of therapy received in the next three-month interval in predicting MADRS scores in the next interval (F=2.77, df=3, 138, p=.044).

The amount of psychotherapy did not predict YMRS mania scores in the concurrent interval. Patients who had higher YMRS scores in the final week of the prior interval had higher YMRS scores at the end of the next interval (F=29.22, df=1, 137, p<.001). There was no interaction between mania scores in the prior interval and psychotherapy use in the current interval in predicting YMRS scores in the current interval.

Lagged associations. To examine whether the associations between psychotherapy and mood symptoms were lagged rather than concurrent, we repeated these analyses by examining service use in the prior interval and MADRS and YMRS scores in the prior interval as predictors of MADRS and YMRS scores in the following interval. This mixed-effects model revealed no main effect of prior service use and a significant main effect of depression in the prior interval on depression in the current interval (F=20.93, df=1, 137, p<. 001). There was an interaction between depression and psychotherapy use in the prior interval in predicting depression in the current interval that approached but did not reach significance. Among patients who had more severe depression at the end of the previous interval, receiving four or more psychotherapy sessions in that interval was associated with less severe depressive symptoms by the end of the next interval. In contrast, among patients with less severe depression in the previous interval, obtaining three or fewer sessions in that interval was associated with lower MADRS scores by the end of the next interval.

YMRS scores, sex, or history of depressive episodes in the prior interval did not predict depression in the next interval, although independent effects of income (F=3.71, df=2, 137, p=.027) and marital status (F=5.55, df=1, 137, p=.02) were again observed.

There was no association between service use in the prior interval and patients' YMRS scores in the next interval. There was also no interaction between prior YMRS scores and prior service use in predicting future YMRS scores.

Amount of service use and functional outcomes

A final mixed-effects regression model examined the relations between psychotherapy and subsequent role functioning (LIFE-RIFT scores) after controlling for the effects of prior role functioning. Because role-functioning scores change more slowly than symptom scores among patients with bipolar disorder ( 25 ), we reasoned that the association between psychotherapy and role-functioning scores would be lagged rather than concurrent.

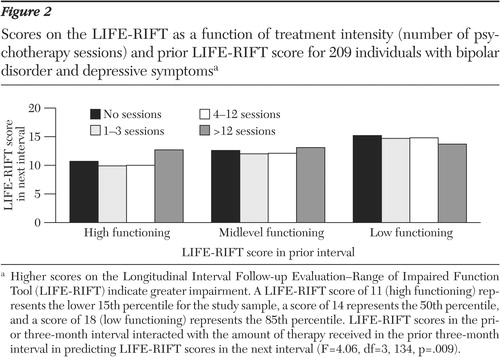

The results of the lagged prediction analyses are presented in Figure 2 . Patients who received 12 or fewer psychotherapy sessions in the prior interval were on average higher in functioning in the next interval than patients who received more than 12 sessions in the prior interval (F=5.73, df=3, 134, p=.001). There were independent effects of LIFE-RIFT scores in the prior interval on role-functioning scores in the current interval (F=66.02, df=1, 134, p<.001).

a Higher scores on the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-Range of Impaired Function Tool (LIFE-RIFT) indicate greater impairment. A LIFE-RIFT score of 11 (high functioning) represents the lower 15th percentile for the study sample, a score of 14 represents the 50th percentile, and a score of 18 (low functioning) represents the 85th percentile. LIFE-RIFT scores in the prior three-month interval interacted with the amount of therapy received in the prior three-month interval in predicting LIFE-RIFT scores in the next interval (F=4.06, df=3, 134, p=.009).

There was an interaction between role functioning in the prior interval and the amount of therapy received in that interval in predicting role functioning in the next interval (F=4.06, df=3, 134, p=.009). This interaction ( Figure 2 ) indicated that among patients with lower prior role functioning (higher LIFE-RIFT scores in the prior interval), receiving more than 12 psychotherapy sessions in the prior interval was associated with better functioning in the next interval (lower LIFE-RIFT scores) than was receiving 12 or fewer sessions. In contrast, among patients with higher prior role functioning, receiving 12 or fewer sessions in the prior interval was associated with better role functioning (lower LIFE-RIFT scores) in the next interval than was receiving more than 12 sessions.

Independently, patients with higher income had better LIFE-RIFT scores in the current interval than patients with lower income (F=6.43, df=2, 134, p=.002). No effects of patients' sex, marital status, MADRS scores (prior interval), or number of prior depressive episodes were observed on role-functioning scores.

Discussion

This study examined the association between psychotherapy usage and depression symptoms, mania symptoms, and role functioning among patients in a depressive phase of bipolar disorder who were followed over one year in the STEP-BD program. Our conclusions are threefold. First, 60 percent of the patients opted for at least one adjunctive psychotherapy session during the first year of STEP-BD. The correlates of amount of service use were having fewer prior episodes of depression and, to a lesser extent, being unmarried. A prior retrospective study based on the first 500 entrants into STEP-BD revealed that high psychotherapy users during the three-month prestudy interval had lower global functioning and more comorbid disorders and were more likely to be unmarried than low service users ( 11 ). Thus psychotherapy intervention may be most frequently sought by (or offered to) patients with bipolar disorder who are socially isolated, who are earlier in the course of their illness, or who have more comorbid disorders.

Our second conclusion is that the association between amount of psychotherapy and symptomatic or functional outcomes in any given interval varied according to whether the patient was less or more severely ill at the end of the prior interval. In cross-lagged analyses, the association between psychosocial service use and symptom or functional outcomes could be observed beyond the robust effects of prior symptomatic states. Patients who were more depressed or lower in functioning at the beginning of an interval and who had more frequent—weekly or at least biweekly—psychotherapy contacts had less severe depressive symptoms in the same interval and better role functioning in the next interval than those who had fewer psychotherapy contacts. In contrast, less severely depressed patients and patients with higher functioning who had fewer sessions of therapy had lower depression scores in the same interval and better functioning scores in the next interval than those who had more sessions.

These results are consistent with randomized trials in showing that psychotherapy does not always have a beneficial impact within the time frame of observation. Randomized trials among patients with bipolar disorder have consistently documented the benefits of adjunctive psychotherapy at intermediate- and long-term follow-up but not always during the immediate phase after illness ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). In our study, the association between treatment use and role functioning was lagged rather than concurrent. This introduces a hypothesis to examine in future randomized trials: treatment-associated changes in symptoms are temporal precursors to treatment-associated changes in role functioning.

We recommend further investigation of the possibility that less severely ill or more functional patients with bipolar disorder benefit from less frequent psychotherapy sessions. Possibly, less severely ill patients are more adherent to pharmacotherapy than more severely ill patients ( 26 ) and hence are less dependent on adjunctive psychotherapy for mood stability. Alternatively, less severely ill patients may be more likely to become dysregulated by the emotional content that arises in weekly or more intensive psychotherapy but to benefit from the support provided during maintenance check-ins. Although emotional distress and transient symptom exacerbation can be precursors to positive change in posttraumatic stress disorder ( 27 ) and major depressive illness ( 28 , 29 ), it is not clear whether this is the case among patients with bipolar disorder.

In interpreting these findings, it is important to highlight that the design of a naturalistic psychotherapy study differs considerably from the design of a controlled clinical trial. Controlled trials provide strong evidence for the benefits of select forms of psychotherapy as provided in structured, weekly formats ( 1 , 2 ). In contrast, we had little information about the type, structure, or quality of psychotherapy provided to patients in this study. Thus the treatments obtained by patients may have differed substantially from the treatments shown to be effective for bipolar disorder in controlled trials. The anxiety disorders literature also documents a disparity between the type of care investigated in clinical trials and the care offered in the community ( 30 ).

Furthermore, patients obtained an average of only eight psychotherapy sessions during the study year, substantially fewer than the amount usually offered in randomized trials ( 1 , 2 ). Whereas this treatment dosage may be typical for patients with bipolar disorder in community care settings, it raises the possibility that a higher dosing of psychotherapy would have been associated with better results.

By design, some of the randomized psychotherapy trials for bipolar disorder included only patients who began treatment in states of recovery ( 3 , 9 ), whereas others included patients during or shortly after an acute affective episode ( 5 , 7 , 8 ). In contrast, naturalistic designs do not constrain changes in patients' symptomatic states, the frequency of psychotherapy, or particularly, escalations in the frequency of care in response to symptom change. For example, an increasing severity of illness may have driven the number of sessions the patients received during a study interval, resulting in a negative correlation between service use and symptom outcome among patients who began the interval in less symptomatic states.

We examined psychotherapy only as given by psychologists, social workers, mental health counselors, or nurses. We did not quantify the amount of psychotherapy given in the context of psychopharmacology sessions by psychiatrists. The STEP-BD protocol encouraged psychiatrists to offer brief, supportive clinical management in addition to pharmacological care ( 10 ). It is possible that some patients received few psychotherapy sessions from nonpsychiatric personnel because they were simultaneously engaged in regular psychotherapy sessions with their psychiatrist. We see value in studies that examine the clinical effects of psychotherapeutic interventions as delivered by psychiatrists in the context of pharmacological management.

Our study was not designed to address questions concerning the relation of therapy format (individual, group, or family sessions), theoretical orientation, or specific treatment techniques (such as relapse prevention planning or sleep-wake stabilization) to the fluctuating course of bipolar disorder. We also cannot rule out the explanatory roles of patient variables, such as attitudes toward psychotherapy, or provider variables, such as clinical experience with patients with bipolar disorder or preferred prescribing practices.

Finally, future studies should examine therapeutic change processes over shorter time intervals than those examined in this study, so that investigators can sequentially observe the lags between treatment sessions; early shifts in affect, cognition, or behavior; and symptomatic change ( 31 ). Such research can help clinicians determine the proper dosages and duration of treatments, the signs that gains are likely to soon occur, and ways to consolidate gains over the long term.

Conclusions

This study provides correlational support for the hypothesis that patients with bipolar disorder who are more severely ill and functionally impaired benefit from more intensive adjunctive psychotherapy, whereas patients who are less severely ill and impaired benefit from less frequent contacts. We recommend that these findings be reevaluated in randomized effectiveness trials that systematically vary the amount of psychotherapy offered to patients and examine the moderating effects of initial symptoms and functioning. The results from the randomized acute depression arm of the STEP-BD study will be able to provide an initial test of this hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by contract N01-MH80001 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIMH. This article was approved by the publication committee of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Details of the STEP-BD project can be found at www.stepbd.org.

1. Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW: New psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder: a review of literature and introduction of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, in pressGoogle Scholar

2. Otto MW, Miklowitz DJ: The role and impact of psychotherapy in the management of bipolar disorder. CNS Spectrums 9(suppl 12):27-32, 2004Google Scholar

3. Lam DH, Hayward P, Watkins ER, et al: Relapse prevention in patients with bipolar disorder: cognitive therapy outcome after 2 years. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:324-329, 2005Google Scholar

4. Scott J, Garland A, Moorhead S: A pilot study of cognitive therapy in bipolar disorders. Psychological Medicine 31:459-467, 2001Google Scholar

5. Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Richards JA, et al: A randomized study of family-focused psychoeducation and pharmacotherapy in the outpatient management of bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:904-912, 2003Google Scholar

6. Perry A, Tarrier N, Morriss R, et al: Randomised controlled trial of efficacy of teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatment. British Medical Journal 16:149-153, 1999Google Scholar

7. Rea MM, Tompson M, Miklowitz DJ, et al: Family focused treatment vs. individual treatment for bipolar disorder: results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71:482-492, 2003Google Scholar

8. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Thase ME, et al: Acute treatment with interpersonal and social rhythm therapy prolongs the well interval in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:996-1004, 2005Google Scholar

9. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, et al: A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:402-407, 2003Google Scholar

10. Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, et al: Rationale, design, and methods of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Biological Psychiatry 53:1028-1042, 2003Google Scholar

11. Lembke A, Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, et al: Psychosocial service utilization by patients with bipolar disorders: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 10:81-87, 2004Google Scholar

12. Kogan JN, Otto MW, Bauer MS, et al: Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the first 1000 patients enrolled in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Bipolar Disorders 6:460-469, 2004Google Scholar

13. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders. New York, Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1995Google Scholar

15. Sachs GS: Use of clonazepam for bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51:31-34, 1990Google Scholar

16. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(suppl 20):22-33, 1998Google Scholar

17. Sachs G, Printz D, Kahn D, et al: Medication treatment of bipolar disorder. Expert Consensus Guideline Series. Postgraduate Medicine Apr:1-104, 2000Google Scholar

18. Montgomery A: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry 134:382-389, 1979Google Scholar

19. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, et al: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity, and sensitivity. British Journal of Psychiatry 133:429-435, 1978Google Scholar

20. Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, et al: The Range of Impaired Function Tool (LIFE-RIFT): a brief measure of functional impairment. Psychological Medicine 29:869-878, 1999Google Scholar

21. Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, et al: A brief assessment of psychosocial function of subjects with bipolar I disorder: the LIFE-RIFT (Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation-Range of Impaired Function Tool). Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:805-812, 2000Google Scholar

22. Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH: Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:310-317, 2004Google Scholar

23. Ger D, Everitt BS: Handbook of Statistical Analyses Using SAS, 2nd ed. London, CRC Press, 2001Google Scholar

24. Nolen-Hoeksema S: Sex differences in unipolar depression: evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin 101:259-282, 1987Google Scholar

25. Keck PE Jr., McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al: Twelve-month outcome of patients with bipolar disorder following hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:646-652, 1998Google Scholar

26. Keck PE Jr., McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al: Factors associated with pharmacologic noncompliance in patients with mania. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:292-297, 1996Google Scholar

27. Jaycox LH, Foa EB, Morral AR: Influence of emotional engagement and habituation on exposure therapy for PTSD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:185-192, 1998Google Scholar

28. Hayes AM, Strauss J: Dynamic systems theory as a paradigm for the study of change in psychotherapy: an application to cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:939-947, 1998Google Scholar

29. Hayes AM, Beevers CG, Feldman GC, et al: Avoidance and processing as predictors of symptom change and positive growth in an integrative therapy for depression. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 12:111-122, 2005Google Scholar

30. Goisman RM, Warshaw MG, Keller MB: Psychosocial treatment prescriptions for generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia, 1991-1996. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1819-1821, 1999Google Scholar

31. Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ: Sudden gains and critical sessions in cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 67:894-904, 1999Google Scholar