Performance Measures for Early Psychosis Treatment Services

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the feasibility of identifying performance measures for early psychosis treatment services and obtaining consensus for these measures. The requirements of the study were that the processes used to identify measures and gain consensus should be comprehensive, be reproducible, and reflect the perspective of multiple stakeholders in Canada. METHODS: The study was conducted in two stages. First a literature review was performed to gather articles published from 1995 to July 2002, and experts were consulted to determine performance measures. Second, a consensus-building technique, the Delphi process, was used with nominated participants from seven groups of stakeholders. Twenty stakeholders participated in three rounds of questionnaires. The degree of consensus achieved by the Delphi process was assessed by calculating the semi-interquartile range for each measure. RESULTS: Seventy-three performance measures were identified from the literature review and consultation with experts. The Delphi method reduced the list to 24 measures rated as essential. This approach proved to be both feasible and cost-effective. CONCLUSIONS: Despite the diversity in the backgrounds of the stakeholder groups, the Delphi technique was effective in moving participants' ratings toward consensus through successive questionnaire rounds. The resulting measures reflected the interests of all stakeholders.

Over the past decade comprehensive approaches to the early detection and treatment of psychosis have been developed (1). The goals of such early intervention services include reduction in delays for initial treatment, reduction of secondary morbidity in the postpsychotic phase of the illness, and reduction of stress among families and caregivers.

Because early intervention services are a recent development, systematic evaluation of the quality of care provided in such programs is of particular importance. Early intervention services for psychosis have been identified as complex care systems (2). They combine multiple evidence-based interventions (3) but may not themselves be specific interventions. Randomized controlled studies have not shown clear-cut benefits for specialized early intervention services for psychosis in comparison with treatment as usual (4,5,6). It has been argued that randomized controlled trials have limitations for evaluating socially complex services (7). Effectiveness studies may represent an alternative methodology (8). However, identifying performance measures is a necessary step toward designing effectiveness studies that can be generalized, thus creating an evidence base to evaluate whether programs such as specialized early intervention services for psychosis should become standards of care.

Performance measurement has been defined as "the use of both outcome and process measures to understand organizational performance and effect positive change to improve care" (9). Performance measures can be used to evaluate the quality of care provided and to assist health care providers in improving the quality of health care. Quality of care can be conceptualized in terms of structure, process, and outcome measures (10). Performance measures can be used to assess the quality of care at four different levels: client or clinical, service or program, system, and population (11). This article discusses performance measures appropriate for assessment at the service level. Process and outcome information can be used to assess quality of care when evidence suggests that the treatment provided affects patient outcome (12). For example, in the treatment of schizophrenia, extensive research has demonstrated the effectiveness of both pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments (13,14,15).

Quality improvement is increasingly recognized as an intrinsic part of health services delivery. In addition, funders of health care are demanding accountability and adherence to evidence-based practice. Performance measurement represents a strategy for addressing both quality improvement and accountability in health care. Ideally, performance measures should be based on evidence (16). The evidence can be derived from evidence-based guidelines or more directly from literature reviews of the evidence that supports specific measures. Even when the base of evidence is limited, guidelines and performance measures can be developed (17).

We describe an evidence-based approach to identify and select performance measures for early psychosis treatment services. The study comprised two phases. In the first, we reviewed the published and unpublished literature on performance measurement to compile an initial, comprehensive list of individual measures with potential application to early intervention programs. Published sets of performance measures specifically for early psychosis programs were not available. In the second phase of the project, additional measures were identified in the first round of the consensus process, which were narrowed and refined through the second and third round of the Delphi process, a consensus-building technique (18).

Methods

The literature review was based on two sources of information: online databases and reports from governments and professional organizations. The databases were searched for English-language articles on performance measurement published between 1995 and July 2002 and included MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, CINAHL, and HealthSTAR. The following phrases were independently used in the search: performance measure, quality indicator, process measurement, outcome measurement, and quality of care. The search was focused on measures used in health and mental health care. In addition, a Web search of online government reports and professional practice organization reports was performed. Citations in articles were reviewed, and advice was sought from experts in the field to identify additional performance measures.

The database searches yielded a total of 492 unduplicated references, with appropriateness and eligibility for inclusion in the current review determined by abstract screening. Inclusion criteria consisted of the following: the focus of the abstract was performance measurement or quality of care evaluation and either the abstract represented a review of performance measure work or the abstract presented research evidence that was based on at least one identified measure with face validity. A total of 142 references met the inclusion criteria and were individually reviewed. The overall distribution of publications by country was as follows: the United States (95 publications, or 67 percent), the United Kingdom (27 publications, or 19 percent), Canada (17 publications, or 12 percent), and Australia (three publications, or 2 percent). In total, 73 performance measures were identified in the literature, including eight with categorical definitions. These measures were classified into eight domains defined by the Canadian Institute of Health Information (19). The domains included acceptability, accessibility, appropriateness, competence, continuity, effectiveness, efficiency, and safety.

Professional and accrediting organizations have published guidelines and standards, and these were also included in our list of performance measures (20,21,22,23). In addition, a number of government-initiated or government-sponsored reports and references were identified. The U.S. National Inventory of Mental Health Quality Measures was developed by the Center for Quality Assessment and Improvement in Mental Health. The inventory is a catalogue of measures that are operationalized, evidence based, and empirically tested. It is available for use at www.cqaimh.org.

In the United States Hermann and colleagues (24) conducted a review of measures proposed for application to mental health care that were specific to schizophrenia. Forty-two process measures were identified. Twenty-five measures (60 percent) were based on research evidence that linked measure conformance with improved patient outcomes. Only 12 measures (29 percent) were fully operationalized. Few were tested for reliability or validity. The authors aptly state that these data provide a "snapshot of the status of schizophrenia process measurement amid its ongoing development."

In Australia a set of performance measures was developed to monitor the progress of the National Mental Health Strategy (25); also available is the Australian Clinical Guidelines for Early Psychosis (26).

A key innovation in the United Kingdom is the development of National Service Frameworks, which intends to set national standards and define service models for specific services or care groups, to design programs that support implementation, and to establish performance measures for use in creating benchmarks (27). The National Center for Health Outcomes Development recommended a set of 20 outcome measures for severe mental illness (28).

A number of performance measures that assessed clinical status (effectiveness domain) were found in at least two types of sources—that is, government reports, published literature, and professional practice organization reports. In addition, most of the measures within the acceptability and appropriateness domains were similarly found in at least two types of sources (78 percent and 65 percent, respectively). This finding would suggest that our searches had reached a degree of saturation.

Table 1 provides the descriptions and the sources (19,20,21,22,2326,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52) of the performance measures in all eight domains.

The Delphi technique has been widely used in health care research and mental health services research, including in the identification of key components of schizophrenia care (53), the description of service models of community mental health practice (54), the characterization of relapse in schizophrenia (55), and the identification of a set of quality indicators for primary care mental health services (56).

Although historically the Delphi technique, a consensus method, has been used with a panel of experts, it has been argued that it is important to broaden the stakeholder groups to include clinicians, consumers, payers, and providers (10,57). Although experts in developing and evaluating the evidence base need to be involved in selecting performance measures, it is vital that the perspective of other stakeholders be included. For example, the organization that pays for the service will likely focus on the cost-effectiveness of care, whereas consumers will likely focus on access and acceptability. Another benefit of including multiple stakeholders is to garner support for the implementation of the services (58). In addition, the consensus technique was used to reduce the number of measures to a more manageable amount.

Consensus methods are structured facilitation techniques that explore consensus among a group by synthesizing opinions. Although a variety of consensus techniques exist (59), all sharing the common objective of synthesizing judgments when a state of uncertainty exists, the Delphi has four important features. First, it is characterized by its anonymity, thus encouraging honest opinion free from group pressure (60). This method is an advantage when both consumers and clinical experts are included, lest the experts dominate discussions. Second, iteration allows stakeholders to change their opinions in subsequent rounds. Third, controlled feedback illustrates the distribution of the group's response, in addition to the individual's previous response. Finally the Delphi technique can be used to engage participants who are separated by large distances because it can be distributed by mail or online (61). This method therefore was appropriate to use in the selection of a core set of performance measures for application to early psychosis treatment services.

The list of performance measures that resulted from the literature review was developed into a Delphi questionnaire. This questionnaire was first pilot tested and refined with three individuals who were familiar with early psychosis treatment services. Pilot testing involved individual, in-person administration of the questionnaire by a research coordinator to a patient, family member, and staff member in the local early treatment program for psychosis. The research coordinator asked these three individuals about the clarity of the instructions, definitions, and descriptions of the performance measures.

The following eight domains constitute the framework: acceptability, accessibility, appropriateness, competence, continuity, effectiveness, efficiency, and safety. Definitions were provided for each domain and for each of the five ratings on a Likert scale. Possible scores ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 representing essential and 5 unimportant.

In the next phase of the study, questionnaires were presented in three rounds to a panel of purposefully selected stakeholders. Purposive sampling is a nonprobability sampling technique in which participants are not randomly selected but instead are deliberately selected to capture a range of specified group characteristics. This form of sampling is based on the assumption that the researcher's knowledge of the population can be used to carefully select individuals to be included in the sample (62). For this particular study purposive sampling is superior to the alternatives because the stakeholders were selected on the basis of their breadth of experience and knowledge, as well as their willingness and ability to articulate their opinions. Optimal sample size in research with the Delphi technique has not been established. Research has been published that was based on samples that vary from between 10 and 50 to much larger numbers (63). Murphy and colleagues (59) asserted that a larger sample is better, concluding that as the number of stakeholders increases, the reliability of "composite judgment" increases. However, these authors also stated that there is scant empirical evidence about the effect of the number of stakeholders on either the reliability or the validity of consensus processes.

The Delphi panel comprised seven stakeholder groups. It was our goal to have four participants from each of the stakeholder groups complete the Delphi process. The members of the stakeholder groups were selected from four levels: national, provincial, regional, and service. The expert group was selected at the national level and the payer group was selected from health ministry officials from the provincial government, because in Canada the provincial governments are responsible for funding and the delivery of health care. Two groups were selected at the regional level. The regional level consists of a single regional health authority, which is the health provider organization legally mandated to provide the continuum of health care services to the entire population in the region. In this case the regional health authority serves 1.2 million individuals. The two groups selected at the regional level were senior administrators and family physicians. Finally, three groups—families, consumers, and clinicians—were selected at the service level.

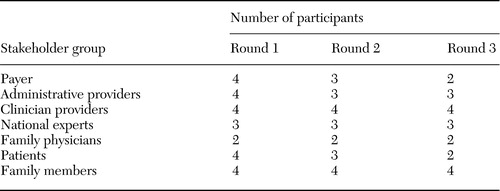

The seven stakeholder groups that formed the panel and the numbers of participants within each group are listed in Table 2.

During the proposal-writing stage, the primary author contacted nationally recognized experts, government representatives from the Ministry of Health and Wellness (payer group), and administrative representatives from the provider organization to explain the project and details of participation (Table 2). A list of family physicians that most frequently referred patients to the local early treatment program for psychosis was also identified. Potential family and consumer participants were identified by staff of the local early treatment program for psychosis.

The selection of the mental health care providers differed from that of the selection of the rest of the stakeholder groups. Rather than purposefully select four stakeholders, the research team invited all staff members of the local early treatment program for psychosis to participate in the Delphi technique and randomly sampled four of the seven participants' questionnaires for inclusion in our analysis.

The Delphi questionnaire was administered by the research coordinator in person to each member of the patient stakeholder group. All other stakeholders received a written questionnaire, either by e-mail or post. The stakeholders were asked to rate the importance of individual measures in the evaluation of quality of care in early psychosis programs. Each round of questionnaires included a qualitative component that offered the opportunity to provide additional feedback in the form of written comments. After round 2 and round 3, the degree of consensus achieved in the Delphi process was assessed by calculating the semi-interquartile range of the score assigned by the stakeholder for each measure (54).

The semi-interquartile range is calculated as (75th percentile-25th percentile)/2.

The level of consensus was set before data were collected. Consensus was defined as being reached when measures attracted final scores with a semi-interquartile range of .50 (absolute). Measures with final scores with a semi-interquartile range of less than .50 were interpreted as having reached strong group consensus (54).

Each round built on responses to the former round. Stakeholders were provided with a summary of the series of rounds. This summary included the feedback to each stakeholder: his or her own score on each item, the group's median ratings, and a synopsis of written comments. Stakeholders were then asked to reflect on the feedback and rerate each item in light of the new information.

In round 1, 25 stakeholders were asked to list five to ten performance measures that they believed to be important in the evaluation of the quality of care in early psychosis treatment services. The suggested performance measures were analyzed by using thematic content analysis with the Nud*ist (Non-numerical Unstructured Data Indexing Searching and Theorizing) computer software program (64). This qualitative analysis was conducted only on this first round and not on subsequent rounds and resulted in the identification of 11 potential performance measures that were not identified by the literature review.

As shown in Table 2, a total of 22 of the 25 original stakeholders participated in round 2. Three stakeholders withdrew, one from the payer group, one from the mental health administrative group, and one from the patient group. A questionnaire containing a comprehensive list of performance measures was distributed to participants. This list of 83 measures comprised the 73 items identified in the literature review plus ten additional items that were suggested in the first open-ended round of the Delphi process. Participants were asked to rate each of the measures on a 5-point Likert scale to determine the degree to which they thought the measure was essential.

Twenty of the 22 participants from the previous round participated in round 3 (Table 2). One patient became ill and was hospitalized, and one stakeholder in the payer group withdrew from the study. Each performance measure was listed with the participant's own rating from the previous round, the median rating of the group, and the percentage of participants who responded to each rating on the Likert scale. Participants were asked to rerate each measure in light of this new information. In the event that their response was more than two points away from the group median, they were asked for elaborative comments.

Results

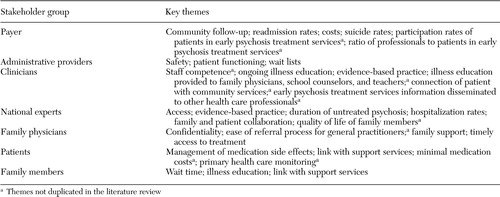

Although there was some thematic overlap in responses among the seven stakeholder groups in round 1, participants from different stakeholder groups valued different measures. Responses are summarized in Table 3.

Quantitative data from round 2 and round 3 were analyzed (medians, means, and semi-interquartile ranges) (65). At the end of round 3 an overall consensus was present for 69 measures (83 percent). The 24 measures rated as essential are reported in Table 4.

Discussion

This is the first reported study to develop a set of performance measures specifically designed to evaluate early intervention services for psychosis. These measures are relevant for all mental health programs that provide services to individuals who experience a first episode of psychosis. They were not developed to evaluate only one specific model of early intervention services for psychosis; as a result, their validity does not depend on evidence from clinical trials or meta-analyses stating that one form of early psychosis is more effective than another (66). Furthermore, the stakeholder consensus process established the face validity of these performance measures (67). Publication of this set is timely because of the interest in innovative early intervention services for psychosis and the current lack of certainty about their superiority over treatment as usual (4,5,6). As such the measures will be particularly relevant in the United States, where there has been less emphasis on the development of specific early-intervention services for psychosis.

The responses from the open-ended question in the first round of the Delphi technique were illuminating in that results indicated that different stakeholder groups tended to value different performance measures. For example, the experts emphasized the importance of access, perhaps reflecting their knowledge about the link between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome (67); the payers emphasized readmission rates and costs; the patients emphasized management of side effects; and the families emphasized illness education.

Thirteen of the measures within the effectiveness domain were rated as essential or very important during the third round. This domain is particularly well developed and perhaps reflects the general trend in reporting outcome.

Given the diversity of the group, it is surprising that consensus was reached on a majority of measures in two rounds of the questionnaire (rounds 2 and 3). Future research could examine the reasons behind the opinion change. How participants behave between rounds and the reasons for their opinion change is an interesting psychological issue (68). Other than in the first round, we did not conduct a thematic analysis on the qualitative responses, because it was beyond the scope of this study to analyze the effect of the qualitative comments on the subsequent decision making of stakeholder groups.

This study has a number of limitations. The measures rated were based on a literature search up to July 2002. The composition of stakeholder panels used in the Delphi technique is an important factor in judging the legitimacy of the findings, and some of the groups were drawn from only one region (63). Attrition was a concern, such that the numbers in some of the stakeholders groups were not equivalent (Table 2). Because of differences in group size in round 3, the results could be biased in favor of the mental health clinician providers and the family members.

At this stage of research the reproducibility of the results of this approach is not known. However, the Delphi technique used in this study has been clearly described and can be replicated by other investigators. Although the performance measures listed in Table 4 represent consensus among the various stakeholders, some of the measures, such as knowledge and application of evidence-based practice and formal and continuing education of early psychosis treatment services staff—could be considered to be professional aspirations (56).

Finally, although the significant benefits of the Delphi process are outlined above, the process itself has limitations. The major concern is that only limited feedback was included between rounds. Also, the process does not allow for face-to-face discussion, which is allowed by consensus development conferences (69). Although other consensus techniques, such as the Nominal Group Technique RAND Appropriateness Method, have been used (69), each technique has its own strengths and weaknesses.

Conclusions

We chose not to exclude measures from the final list of 73 items at this stage. However, because the data collection and reporting burden will be too great for the full set, further reduction will be necessary to select a minimum optimal number. Reducing the number of measures will not preclude stakeholders from adding to the set if they decide that their critical needs are not being met. For example, payers might demand inclusion of measures of cost that they deem relevant, whereas experts are more likely to add process and outcome measures as the scientific literature evolves.

This large potential set of performance measures is more than sufficient to assess the goals and outcomes of early intervention services for psychosis. However, a number of processes will help guide the eventual selection. These processes include both the strength of the evidence that will link process and outcome measures and the cost and ease of data collection. Given that considerable development of information systems is currently under way, it is timely to know what it is desirable to measure in order to take advantage of the opportunity to influence routinely collected information. A further possibility is to consider more detailed assessment of new programs and at greater cost. Once their value is established, smaller data sets are required to monitor performance. Finally, the impact of basic sociodemographic factors on key outcome measure needs to be accounted for by risk adjustment (70) in order to establish benchmarks that will allow comparisons between services (71).

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grant 16009 from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

Dr. D. Addington, Ms. McKenzie, Dr. Patten, Dr. Smith, and Dr. Adair are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada. Dr. Patten is also with the department of community health sciences at the university. Dr. Smith is also with the information and evaluation unit at Calgary Health Region. Dr. J. Addington is with the Centre for Addition and Mental Health at the University of Toronto. Send correspondence to Dr. D. Addington at the Foothills Medical Centre, 1403 29th Street, N.W., Special Services Building, Second Floor, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 2T9 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Performance measures for the evaluation of quality of care in early psychosis treatment servicesa

a Performance measures gathered from a literature review, reports from governments and professional organizations, and consultation with experts in the field

|

Table 2. Stakeholder groups and number of participants within each round of the Delphi process

|

Table 3. Performance measures that stakeholders suggested in round 1 of the Delphi process as being important in the evaluation of quality of care in early psychosis treatment services

|

Table 4. Performance measures that stakeholders rated as essential in the evaluation of quality of care in early psychosis treatment services with strong group consensusa

a Semi-interquartile range of <.50 indicates consensus.

1. The Recognition and Management of Early Psychosis: A Preventive Approach. Edited by McGorry PD, Jackson H. Melbourne, Cambridge University Press, 1999Google Scholar

2. Marshall M, Lockwood A, Lewis S, et al: Essential elements of an early intervention service for psychosis: the opinions of expert clinicians. BioMed Central Psychiatry 4:17,2004Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, et al: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:193–217,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Craig TK, Garety P, Power P, et al: The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. British Medical Journal 329:1–5,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kuipers E, Holloway F, Rabe-Hesketh S, et al: An RCT of early intervention in psychosis: Croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team (COAST). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 39:358–363,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Abel M, et al: OPUS study: suicidal behaviour, suicidal ideation, and hopelessness among patients with first-episode psychosis: one-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. British Journal Psychiatry 181(suppl):S98-S106, 2002Google Scholar

7. Wolff N: Using randomized controlled trials to evaluate socially complex services: problems, challenges, and recommendations. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 3:97–109,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wells KB: Treatment research at the crossroads: the scientific interface of clinical trials and effectiveness research. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:5–10,1999Link, Google Scholar

9. Nadzam DM, Nelson M: The benefits of continuous performance measurement. Nursing Clinics of North America 32:543–559,1997Medline, Google Scholar

10. Donabedian A: The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA 260:1743–1748,1988Google Scholar

11. Tansella M, Thornicroft G: A conceptual framework for mental health services: the matrix model. Psychological Medicine 28:503–508,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Norquist G: Role of outcome measurement in psychiatry, in Outcome Measurement in Psychiatry: A Critical Review. Edited by IsHak WW, Burt T, Sederer LI. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002Google Scholar

13. Dixon LB, Lehman AF, Levine J: Conventional antipsychotic medications for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:567–577,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Dixon LB, Lehman AF: Family Interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:631–643,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Tarrier N, Yusupoff L, Kinney C, et al: Randomised controlled trial of intensive cognitive behaviour therapy for patients with chronic schizophrenia. British Medical Journal 17:303–307,1998Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Hearnshaw HM, Harker RM, Cheater FM, et al: Expert consensus on the desirable characteristics of review criteria for improvement of health care quality. Quality Health Care 10:173–178,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Naylor CD: Grey zones of clinical practice: some limits to evidence-based medicine. Lancet 345:840–842,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, et al: Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. American Journal Public Health 74:979–983,1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. National Consensus Conference on Population Health Indicators. Ottawa, Canadian Institute for Health Information 1999Google Scholar

20. Addington D, Bassett A, Cook P, et al: Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 43:25S-39S,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Report of the American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Quality Indicators. American Psychiatric Association, 1999Google Scholar

22. Indicators and the AIM Accreditation Program. Ottawa, Canadian Council on Health Services Accreditation, 2001. Available at www.cchsa.caGoogle Scholar

23. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia: American Psychiatric Association. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1–63,1997Google Scholar

24. Hermann RC, Finnerty M, Provost S, et al: Process measures for the assessment and improvement of quality of care for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 28:95–104,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Mental Health Information Development: National Information Priorities and Strategies Under the Second National Mental Health Plan:1998–2003. Canberra, Australia, Mental Health Branch, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, Canberra,1999Google Scholar

26. Australian Clinical Guidelines for Early Psychosis. Melbourne, National Early Psychosis Project, 2000Google Scholar

27. Modern Standards and Service Models. London, National Service Framework for Mental Health, Department of Health, 1999Google Scholar

28. Carlwood P, Mason A, Goldacre M: Health Outcome Indicators: Severe Mental Illness. Oxford, National Centre for Outcomes Development, 1999Google Scholar

29. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Stolar M: Patient satisfaction and administrative measures as indicators of the quality of mental health care. Psychiatric Services 50:1053–1058,1999Link, Google Scholar

30. Hospital Report, 2001: Preliminary Studies: Mental Health: Vol 1. Toronto, University of Toronto, Hospital Report Research Collaborative, 2001. Available at www.hospitalreport.ca/pdf/SR_V1_Feb18.pdfGoogle Scholar

31. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Clinical Indicators: A User's Manual: Psychiatry Indicators. Melbourne, Australia, 1998Google Scholar

32. Ziguras SJ, Stuart GW: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatric Services 51:1410–1421,2000Link, Google Scholar

33. McEwan K, Goldner EM: Accountability and Performance Indicators for Mental Health Services and Supports: A Resource Kit. Ottawa, Government Services Canada, 2000Google Scholar

34. Performance Indicators for Mental Health Services: Values, accountability, evaluation, and decision support. Rockville, Maryland, Mental Health Statistics Improvement Program, Centre for Mental Health Services, 1996Google Scholar

35. Friedman M, Minden S, Bartlett J: Mental health report cards, in Behavioural Outcomes and Guidelines Sourcebook, 2000. Edited by Coughlin K. New York, Faulkner and Gray, 1999Google Scholar

36. Recommended Operational Definitions and Measures to Implement the NASMHPD Framework of Mental Health Performance Indicators. Report submitted to the NASMHPD President's Task Force on Performance Measures, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, 2000. Available at http://nri.rdmc.org/PresidentsTaskForce2001.pdf#search='www.nri.rdmc.org%2FPresidentsTaskForce2001.pdfGoogle Scholar

37. Young AS, Sullivan G, Burnam MA, et al: Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:611–617,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Noseworthy TW, McGurran JJ, Hadorn DC: Waiting for scheduled services in Canada: development of priority-setting scoring systems. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 9:23–31,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Accreditation Organization Workgroup: A Proposed Consensus Set of Indicators for Behavioral Health. American College of Mental Health Administration, 2001Google Scholar

40. Popkin MK, Lurie N, Manning W, et al: Changes in the process of care for Medicaid patients with schizophrenia in Utah's Prepaid Mental Health Plan. Psychiatric Services 49:518–523,1998Link, Google Scholar

41. Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care. London, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002. Available at www.nice.org.uk/pdf/cg1niceguideline.pdfGoogle Scholar

42. Larsen TK, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S: First-episode schizophrenia with long duration of untreated psychosis. British Journal Psychiatry 172(suppl):45–52,1998Google Scholar

43. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: At issue: translating research into practice: the schizophrenia patient outcomes research team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1–10,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Wray NP, Petersen NJ, Soucheck J, et al: The hospital multistay rate as an indicator of quality of care. Health Services Research 34:777–790,1999Medline, Google Scholar

45. Charlwood P, Mason A, Goldacre M, et al: Health Outcome Indicators: Severe Mental Illness. Oxford, National Centre for Health Outcomes Development, 1999Google Scholar

46. McEwan KL, Goldner EM: Keeping mental health reform on course: selecting indicators of mental health system performance. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health 21:5–16,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Review of Best Practices in Mental Health Reform. Ottawa, Health Canada, 1997Google Scholar

48. Sederer LI, Dickey B: Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Baltimore, Md, Williams and Wilkins, 1996Google Scholar

49. Hermann RC: Linking outcome measurement with process measurement for quality improvement: a critical review, in Outcome Measurement in Psychiatry: A Critical Review. Edited by IsHak WW, Burt T, Sederer LI. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002Google Scholar

50. Pandiani JA, Banks SM, Schacht LM: Using incarceration rates to measure mental health program performance. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 25:300–311,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. International Association of Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services: Psychosocial Rehabilitation Toolkit. Toronto, 2000. Available at www.psr.ofcmhap.on.ca/psr_dec99/userman/user_manual.pdfGoogle Scholar

52. Ralph RO: Review of the Recovery Literature: A Synthesis of a Sample of the Recovery Literature. Alexandria, Va, National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning, 2000Google Scholar

53. Fiander M, Burns T: Essential components of schizophrenia care: a Delphi approach. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia 98:400–405,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Fiander M, Burns T: A Delphi approach to describing service models of community mental health practice. Psychiatric Services 51:656–658,2000Link, Google Scholar

55. Burns T, Fiander M, Audini B: A Delphi approach to characterising "relapse" as used in UK clinical practice. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 46:220–230,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Shield T, Campbell SM, Rogers A, et al: Quality indicators for primary care mental health services. Quality Safety in Health Care 12:100–106,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Cleary PD, Edgman-Levitan S: Health care quality: incorporating consumer perspectives. JAMA 278:1608–1612,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services 52:179–182,2001Link, Google Scholar

59. Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, et al: Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technology Assessment 2:i-iv, 1–88, 1998Google Scholar

60. Jones J, Hunter D: Consensus methods for medical and health services research. British Medical Journal 311:376–380,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H: Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32:1008–1015,2000Medline, Google Scholar

62. Polit D, Hungler B: Essentials of Nursing Research. New York, Lippincott, 1997Google Scholar

63. Campbell SM, Cantrill JA: Consensus methods in prescribing research. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 26:5–14,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. NUD*IST version 4.0 software: Non-numerical Unstructured Data Indexing Searching and Theorizing. QSR, 1997Google Scholar

65. Statistical Package for Social Sciences: SPSS 2001: SPSS version 11.01 statistical software Chicago, SPSS Inc, 2003Google Scholar

66. Cooper B: Evidence-based mental health policy: a critical appraisal. British Journal of Psychiatry 183:105–113,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Addington J, van Mastrigt S, Addington D: Duration of untreated psychosis: impact on 2-year outcome. Psychological Medicine 34:277–284,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Greatorex J, Dexter T: An accessible analytical approach for investigating what happens between the rounds of a Delphi study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32:1016–1024,2000Medline, Google Scholar

69. Black N, Murphy MK, Lamping D, et al: Consensus development methods: a review of best practice in creating clinical guidelines. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 4:236–248,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Iezzoni LI: Getting started and defining terms, in Risk Adjustment for Measuring Mental Health Outcomes. Edited by Iezzoni LI. Chicago, Health Administration Press, 2003Google Scholar

71. Weissman NW, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, et al: Achievable benchmarks of care: the ABCs of benchmarking. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 5:269–281,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar