Use and Costs of Public-Sector Behavioral Health Services for African-American and White Women

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to identify differences between African-American and white women in the use of behavioral health services and factors associated with these differences. METHODS: In one large public behavioral health system, data on demographic characteristics, financial resources, clinical disorders, service use patterns, and costs of care were analyzed for 10,905 African-American and 19,069 white women between the ages of 18 and 59 years who received behavioral health services in 1997. RESULTS: The African-American women were more likely to be older, never married, unemployed, and eligible for Medicaid and to have a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder or a substance use disorder. African-American women were more likely than white women to receive inpatient substance abuse services and to receive more community-based day treatment services, medication services, and case management services. However, the costs of that care differed by only 2 to 4 percent from those for white women. Presence of a psychotic disorder and co-occurring substance use—need-related factors—were significant predictors of higher inpatient care costs for all the women in the sample. Presence of a psychotic or major affective disorder and eligibility for Medicaid—an enabling factor—were the most significant predictors of higher outpatient costs for the sample. Receipt of more community-based services was significantly and inversely related to inpatient care costs, regardless of race. CONCLUSIONS: In this sample of African-American and white women, consumers' needs were a significant predictor of service use. Patterns of care that were tailored to consumers' needs were not significantly more costly overall.

The need to provide behavioral health services in a cost-effective manner has become paramount with the advent of managed care. Behavioral health administrators and clinical managers are scrambling to serve culturally diverse consumers in both public and private settings with growing budgetary restrictions. The use of behavioral health services is affected by various factors related to consumers' demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, and needs. Consumers' service use patterns may vary widely, depending on how these factors are dealt with in the treatment process, and they ultimately determine the overall costs of services. However, services that meet consumers' needs do not have to be more costly (1).

In this study we illustrated these points by examining differences in demographic, economic, and need-related factors with respect to access to various levels of behavioral health care, service use, and differences in behavioral health care costs between African-American and white women. The study was conducted in a public behavioral health system funded predominantly by Medicaid.

Although the amount of research on the use of mental health and substance abuse services by special subgroups such as women and minorities has grown over the past 20 years, the data have usually been analyzed either by race or by sex (2). However, the literature offers important findings to guide our inquiry into differences in costs and use of services between African-American and white women. Although the overall prevalence of major mental disorders is consistent between the sexes and across ethnic groups, sex differences in the types of disorders have been noted—affective and anxiety disorders are more prevalent among women (3).

Women are also more likely to have certain persistent comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders, such as depression and alcoholism, and associated psychotic features and poorer functioning (4,5). Women who have substance use disorders experience more disability at home and at work or school (6), and evidence suggests that African-American persons are more likely to receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia and to have high levels of undiagnosed affective components to their psychotic symptoms (7,8,9,10).

Women are more likely than men to use outpatient services (11), but the gap between the estimated need for and the use of behavioral health services is most apparent in comparisons of different ethnic groups. When members of ethnic communities experience disabling conditions, they may not be served in the mental health system until their condition warrants intensive acute or subacute services (1). In addition, on entering systems of care, nonwhite consumers are more likely to use services in a less than optimal way—for example, attending relatively few outpatient sessions and dropping out of treatment (1).

Barriers to mental health care have traditionally been viewed in terms of economic disparities, but studies have shown that demographic differences such as sex, age, and race also play a major role, especially in the use of various levels of services. Using data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study to predict differences in use of public and private outpatient mental health services, investigators found that being younger, female, and white predicted use of any mental health services, whereas being male and African American predicted use of public-sector services (12).

In a study of differences in service use between African-American and white elderly consumers, no differences were found in the use of inpatient services or of private treatment, but African Americans were less likely to receive outpatient treatment and also had significantly fewer visits (13). The barriers to receiving substance abuse services that were most prominent among African-American women were responsibility as a mother, a wife, or a partner; low income or lack of insurance; a need for alcohol or drugs to deal with the stress of daily life in the community; fear of losing one's children; and shame after admitting to having a substance use problem (14).

Studies of differences in the use and costs of mental health services between various ethnic groups in a public system showed that total costs of care were 14 percent higher for females than for males and 20 percent lower for African Americans than for three other ethnic groups (15). Few studies comparing the demographic or diagnostic characteristics of African-American and white women receiving behavioral health services have been conducted. The most sophisticated analysis to date focused on a generously insured group of female consumers (16). Thus further analyses of differences in service use between African-American and white women and predictors of differences in treatment costs are warranted.

On the basis of this body of literature, we anticipated that African-American women using public behavioral health services would be more likely to have schizophrenia or serious depression and problems related to substance abuse or dependence. We suspected that their need for services would be greater because of these factors, which might entail a need for longer periods of treatment or more intensive treatment, such as 24-hour care or day treatment programs. These women might also be less likely to have the income or insurance that would give them access to services and might be less likely to stay in outpatient treatment for maintenance care. Finally, we expected that these factors would be associated with higher average costs of care for African-American women. Thus we hypothesized that the most significant predictors of service costs would be ethnicity, diagnosis, type of insurance coverage (such as Medicaid), and receipt of ongoing outpatient services.

Our analyses were guided by the most widely known conceptual model for understanding the use of health care services, the Andersen social behavior model (1,15,16,17). This model specifies three types of factors for explaining the use of health care services: predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need-related factors. Predisposing factors reflect a greater propensity to use services; they include demographic variables, such as age and race, and referral-source variables. Enabling factors reflect whether an individual has the means to gain access to or obtain health services, including income level and type of insurance coverage, such as Medicaid. Need-related factors include clinical diagnosis, symptoms, and level of functioning. We expected that these three types of factors would explain or predict the probability of use of or access to various types of health care services—for example, outpatient or inpatient—as well as the amount of service received, such as the number of visits or days.

We expanded this model to incorporate information about the types of outpatient services a consumer receives during the maintenance phase of treatment. In a system of care, the use of outpatient services, such as medication services, day treatment programs, and case management services, would be expected to reduce the need for or use of more intensive, 24-hour care, such as inpatient or skilled nursing services (1,17). Receipt of these outpatient services was added to the analytic model that predicts service costs while controlling for the effect of the predisposing, enabling, and need-related factors.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in a state-operated mental health system in South Carolina, a state that has both rural and small urban areas—in which the largest city has a population of more than 25,000—and several metropolitan areas—populations of 250,000 or more. During the 1997 calendar year, the system served 29,974 women between the ages of 18 and 59 who were either African American (10,905 women, or 36 percent) or white (19,069 women, or 64 percent). Males and women of other ethnic groups were excluded from this analysis. The study was exempted from institutional review board approval because it was conducted with de-identified data.

The public mental health system includes 17 local mental health centers and two acute psychiatric facilities. A wide range of local services is available, including intensive case management based on the Program for Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) model, other case management services, day rehabilitative services, and dual diagnosis treatment as well as regular office-based outpatient services. In the regular outpatient system, caseloads tend to be high for clinical case managers as well as for psychiatrists and nursing staff. The majority of mental health services available throughout the state are provided through the state mental health department, which also operates the inpatient unit for substance abuse treatment. Substance abuse treatment services in the community are provided by local agencies under contract to the state department of substance abuse services.

For this study, clients' demographic and diagnostic data, information about outpatient services at the 17 community mental health centers, and hospitalization information for the state's inpatient facilities—including inpatient substance abuse treatment—were compiled into one statistical file to enable us to examine services used throughout the system in 1997. Demographic and economic data were self-reported to the facility in which the consumer was treated. Diagnostic information based on DSM-IVcriteria was taken from the latest episode of treatment in 1997 on up to five data elements. Thus multiple diagnoses were captured, including the designated primary diagnosis. Data on statewide outpatient substance abuse treatment were obtained from the state department of substance abuse services. Costs of inpatient and outpatient care were calculated from this information and from cost files of the state mental health department.

The number of days that the consumer was hospitalized in each facility during the year was tallied and multiplied by the average daily cost of providing care at the facility in which the episode occurred. The average unit cost of providing each service at each mental health center, as calculated annually by the state mental health department, was multiplied by the number of visits or hours of services provided by the local mental health center, and totals were summed for the year. These files were subjected to a wide variety of data checking analyses as well as procedures to maximize the integrity of the data and to minimize missing data.

To identify the predisposing, enabling, and need-related factors that best predicted differences between these African-American and white women, a multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted that used nine demographic, diagnostic, and entitlement variables and six levels of treatment service variables that were modeled as independent predictors.

For each unduplicated client in the data file, service use was summed by type of service, because each type is based on different units—for example, hours or half days. Analysis of variance was used to identify differences in service use for clients who were using the six types of behavioral health services.

Finally, in the multiple linear regressions, covariates were grouped into predisposing factors (age, marital status, and referral source), enabling factors (employment status, Medicaid eligibility, and rural residence), and need-related factors (diagnoses of psychotic, affective, and substance use disorders) that were entered simultaneously to determine their relative contribution to each cost equation. The total costs of care for three types of services were dependent variables: psychiatric inpatient, substance abuse inpatient, and psychiatric outpatient.

Results

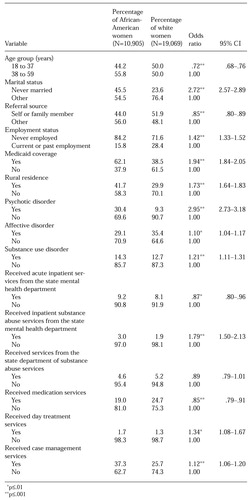

The odds ratios from the multiple logistic regression analysis are listed in Table 1. African-American women were significantly more likely than white women to be in the older group—that is, between the ages of 38 and 59—never married, unemployed, eligible for Medicaid, referred from other service agencies or care facilities, and living in a rural area. They were also significantly more likely to have a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder or a substance use disorder, to have been hospitalized for a substance use problem, and to have received community-based day treatment services and case management services. African-American women also were significantly less likely to have received medication services.

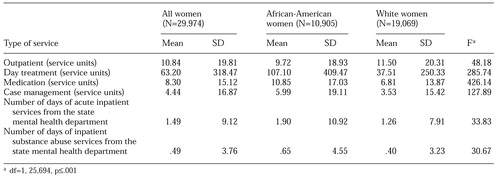

Differences in the use of behavioral health services were then analyzed by service type; the results are summarized in Table 2. Once in the outpatient system, the African-American women received significantly more day treatment services, medication services, and case management services, while the white women received significantly more outpatient services, such as individual, family, or group therapy. The African-American women had slightly longer inpatient stays for psychiatric disorders and for substance use disorders.

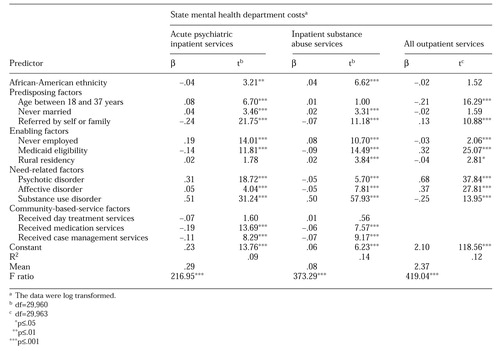

Table 3 gives a summary of the results of the three multiple linear regression analyses of factors associated with total costs of psychiatric inpatient services, inpatient substance abuse services, and outpatient services for African-American and white women. Because the actual costs were skewed—some consumers had low costs while others had very high costs—a logarithmic transformation of the data was performed to normalize the distribution and allow the beta coefficients to be interpreted in percentage terms.

Psychiatric inpatient and outpatient costs were 2 to 4 percent lower for the African-American women than for the white women, and inpatient substance abuse treatment costs were 4 percent higher. On the basis of these results, the main predictors of higher psychiatric inpatient costs in this sample were the presence of a psychotic disorder and the presence of a substance use disorder. For clients who were receiving medication services or case management services in local mental health centers, psychiatric inpatient costs were 19 percent and 11 percent lower, respectively.

The main predictor of the costs of inpatient substance abuse services was an actual diagnosis of substance abuse. The costs of inpatient substance abuse services were only 5 to 6 percent lower for clients who were receiving community-based medication or case management services. Likewise, the costs for clients who were self-referred or referred by a family member were 5 to 6 percent lower. Predictors of higher costs of outpatient psychiatric services were having primarily a psychotic or major affective diagnosis, being eligible for Medicaid, and being self-referred or referred by a family member.

Discussion and conclusions

In this sample of women who received public behavioral health services, demographic, economic, and diagnostic characteristics of African-American women—for example, being older, being unemployed, having a low income, having a substance-related disorder, having multiple problems, or living in a rural area—could have predisposed them toward a need for more intensive behavioral health services but not toward having the means to obtain care. However, not only were they more likely than white women to receive inpatient substance abuse treatment if they had a substance-related disorder, but they also appear to have had their service needs met through longer-term outpatient treatment—that is, they were more likely to use services and had a greater average use of community-based day treatment and case management services.

Given that previous research has shown significantly poorer access to and use of behavioral health services by African Americans, even when economic barriers such as Medicaid eligibility are taken into account, this finding is important and new. The African-American women in this service system appeared to have received services that were consonant with their needs. Their service use patterns were different from those of white women, and the differences led to benefits for the African-American women and the service system. They remained in outpatient treatment longer and therefore avoided inpatient stays. The behavioral health services received by these women appeared to be responsive to some of their gender-based needs as well—for example, the need to remain close to their children or to social or family support while they received treatment for multiple problems.

Such service use patterns could be expected to lead to higher service costs. However, our findings indicate that service costs for inpatient and outpatient care for African-American women were within 2 to 4 percent of those for white women. When the major enabling or economic access barrier of insurance coverage for service use is not an issue, the severity and complexity of the disorder—not ethnicity—appear to be most predictive of the use and costs of outpatient and inpatient care. Providing access to maintenance-level services also keeps inpatient costs lower, although the types and amounts of specific behavioral health services provided may differ significantly.

This study was limited in several ways. It focused only on African-American and white women. It was a cross-sectional, retrospective examination of the administrative data available in only one public mental health system. Inherent limitations of the data include possible miscoding of information, possible diagnostic inaccuracy, and the fact that not all the variables that might have influenced service use were included, as evidenced by the relatively small R2 values in the linear regression equations.

In addition, the data set we used was large. Thus relationships that were statistically significant might not be as meaningful in practice. Finally, information about consumers' functioning and symptoms that was not available in the existing data set would have allowed more precise estimates of the differences between African-American and white women in outcome or need-related factors and add substantially to the predictive models. However, even with these limitations, the results of the study provide insight into the factors that affect service use patterns of African-American women in public behavioral health and the types of community-based services that can meet the needs of African-American women while containing the overall costs of their care.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a contract granted to Dr. Jerrell by the South Carolina Department of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the department of neuropsychiatry and behavioral science of the University of South Carolina School of Medicine in Columbia. Dr. Macey is also with the South Carolina Department of Mental Health in Columbia. Address correspondence to Dr. Jerrell at the Department of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Science, South Carolina School of Medicine, 3555 Harden Street Extension, CEB 104A, Columbia, South Carolina 29203 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Results of multiple logistic regression of characteristics of African-American and white women who received services from the South Carolina Department of Mental Health in 1997

|

Table 2. Use of behavioral health services by African-American and white women who received services from the South Carolina Department of Mental Health in 1997

|

Table 3. Predictors of total costs of mental health and substances abuse services provided to African-American and white women by the South Carolina Department of Mental Health in 1997

1. Jerrell JM: The effects of client-therapist match on service use and costs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 23:119-126, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Padgett DK, Harman CP, Burns BJ, et al: Women and outpatient mental health services: use by black, Hispanic, and white women in a national insured population, in Women's Mental Health Services. Edited by Levin BL, Blanch AK, Jennings A. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1998Google Scholar

3. Weissman MM, Livingston BM, Leaf PJ, et al: Affective disorders, in Psychiatric Disorders in America. Edited by Robins L, Regier D. Toronto, Collier-Macmillan, 1991Google Scholar

4. Klerman GL, Weissman MM: The course, morbidity, and costs of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:831-834, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Cochrane J, Goering P, Lancee W: Gender differences in the manifestations of problem drinking in a community sample. Journal of Substance Abuse 4:247-254, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Rhodes A, Goering P: Gender differences in the use of outpatient mental health services. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:338-346, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Adebimpe VR: Overview: white norms and psychiatric diagnosis of black patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:279-285, 1981Link, Google Scholar

8. Jones BE, Gray GA: Problems in diagnosing schizophrenia and affective disorders among blacks. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:61-65, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Strakowski SM, Lonczak HS, Sax KW, et al: The effects of race on diagnosis and disposition from a psychiatric emergency service. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56:101-107, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

10. Chen YR, Swann AC, Burt DB: Stability of diagnosis in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:682-686, 1996Link, Google Scholar

11. Robins LN, Locke BZ, Regier DA: An overview of psychiatric disorders in America, in Psychiatric Disorders in America. Edited by Robins L, Regier D. Toronto, Collier-Macmillan, 1991Google Scholar

12. Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, et al: Comparing use of public and private mental health services: the enduring barriers of race and age. Community Mental Health Journal 34:133-144, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, et al: Use of mental health services by black and white elderly, in Handbook on Ethnicity, Aging, and Mental Health. Edited by Padgett DK. Westport, Conn, Greenwood, 1995Google Scholar

14. Allen K: Barriers to treatment for addicted African-American women. Journal of the National Medical Association 87:751-756, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hu T, Snowden LR, Jerrell JM: Costs and use of public mental health services by ethnicity. Journal of Mental Health Administration 19:278-287, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, et al: Ethnicity and the use of outpatient mental health services in a national insured population. American Journal of Public Health 84:222-226, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Andersen R, Newman JF: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly: Health and Society 51:95-124, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar