Psychiatry Diversity Leadership in Academic Medicine: Guidelines for Success

Dr. A, a Black woman researcher and clinician-educator in the Department of Psychiatry at a prestigious academic institution, was appointed chair of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) committee in 2017, in the context of public complaints and media coverage concerning sexism and racism. Following recent high-profile murders of Black people by police, Dr. A is called upon by the department chair to develop “antiracist programming.” As a first step, Dr. A drafts a strong message against racism and excessive police force. Despite the statement being vetted by all senior leadership, the department chair insists that Dr. A place only her name on it, in case it is not “well received.” Dr. A receives negative e-mails in response to the statement, with minimal support from the department. Not to be dismayed, Dr. A assembles a DEI committee to plan an “antiracist” strategy for the entire department, without financial support, protected time, or additional resources. The DEI committee progress is slowed by the lack of institutional and departmental commitment. Additionally, several well-meaning non-Black colleagues in the department organize responses to the murders—including protests, town hall events, and public statements—without concerted coordination with the DEI committee, implying that “nothing was being done.” In parallel, Dr. A is tasked with organizing and dispatching the limited number of Black psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers in the department to deliver care to the entire Black community at her institution.

Feeling overwhelmed by the number of tasks she has been asked to initiate—while navigating a tense climate, with minimal financial or administrative departmental support—Dr. A requests a meeting with the department chair and executive committee. At the meeting, Dr. A, a tenured faculty member for the past 10 years, is addressed by another colleague’s name—the only other Black professor in the department. When Dr. A points out this microaggression, a senior colleague tells her she is being “too sensitive,” and is “overreacting.”

Despite this interaction, Dr. A highlights multiple institutional barriers, including the structural racism that minimizes the work of DEI initiatives in the department. She presents her proposal for protected time and resources to successfully execute robust antiracist programming but is told money is tight and to “scale back” and “do the best you can.”

As DEI leaders at major academic psychiatry programs across the United States, we recognize the importance of these positions and advocate for increased support for our activities. Diversity improves productivity, supports recruitment and retention, fosters enhanced innovation, and promotes a more inclusive workforce climate (1). International protests centering on the Black Lives Matter movement—triggered by the recent murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, underscored by a COVID-19 pandemic with racial inequities in morbidity and mortality—have resulted in an urgent need for psychiatry departments to reexamine and commit to fully supporting these leadership positions.

Unfortunately, the case of Dr. A is not unique. DEI leadership roles are typically held by women and/or Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) with limited resources, such as lack of salary support, discretionary funds, and administrative backing (2, 3). As our nation publicly confronts the ongoing trauma of systemic racism, academic institutions are being called to critically evaluate and interface with racism in new ways. DEI leaders are being summoned for one-on-one and programmatic consultation, antiracist curriculum development, antibias training, and skill acquisition. However, many of these institutions do not provide the appropriate resources or support necessary to institute an effective response for cultural change (4). This lack of scaffolding leads to an exacerbation of the “minority tax” (3), thereby placing more duress on the very same people adversely affected by structural racism. As a result, many in DEI leadership positions have become frustrated and disillusioned with the lack of institutional and/or financial support and commitment, leading many to leave academia and organized medicine (4–6).

Academic psychiatry must acknowledge the role that our field has played in creating and perpetuating racist structures and ideas. From this place of recognition, DEI leaders are uniquely poised to use their expertise in understanding attitudes, emotions, behavioral changes, and trauma in order to move toward reconciliation. Implementing strategic decisions related to antiracism and DEI is critically important to promote academic excellence in research, clinical care, and education. Patients, medical students and residents, physicians, and scientists who identify as BIPOC are struggling with the weight of racism and inequity. DEI leaders are critical in guiding departments and institutions across the country to develop structural changes to promote resilience. Below, we outline the current landscape of DEI leadership within psychiatry at academic medical centers and share our vision for how this important role should be structured and compensated.

Current Landscape of Diversity Leaders

We represent DEI leaders at public and private psychiatry departments across the country. Our departments include seven of the top 10 psychiatry departments, according to the 2020 U.S. News & World Report rankings (7). In our small sample (N=9), all are women, and eight (89%) are BIPOC. The mean age is 46 years (range, 40–51 years), seven (77%) are mothers, and four (44%) are informal caregivers of seriously ill family members. Over half of us are the primary breadwinner of their family and/or provide financial support to extended family. The majority of us are psychiatrists, with one psychologist in the sample. In academic rank, our range includes two assistant professors, four associate professors, and three full professors.

We have a wide range of DEI titles, falling into three categories: vice or associate chairs (33%), directors (22%), and diversity ambassadors/members or chairs of diversity committees (44%). Five (56%) of us sit on departmental executive committees. Only one holds a named endowed chair, and four (44%) of us received no compensation or salary support for these roles. For those of us who do receive salary support, the average compensation is $48,000 (range, $10,000–$100,000), representing approximately 18% (range, 5%−36%) of total salary. This is lower than the estimated average effort we report investing in these roles (23%; range, 10%−30%). The unpaid leaders among us estimate spending 16% effort on DEI activities, on average (range, 10%−30%). Only three (33%) of us are provided with support staff (e.g., an administrative assistant), at 25% effort (range, 5%−50%). Five (55%) of us received some discretionary support (average, $27,800; range, $2,000–$100,000), and only two of those five have these funds renewed annually.

Challenges of Limited Representation of Women and BIPOC Faculty in Leadership Positions

DEI roles are challenging for several reasons. Leadership hurdles are often higher for BIPOC women than White men and women, leading to attrition with limited representation (8–10). BIPOC women face additional challenges due to the influence of race and ethnicity on perceptions of leadership (11). BIPOC women experience issues of intersectionality, meaning that they must disentangle whether to attribute workplace discrimination to gender, race, or other aspects of their identity (e.g., disability, sexual orientation) (12).

Leadership Hurdles and Lack of Representation

BIPOC psychiatry faculty typically endure discrimination and lack peers who look like them to provide support. In 2019, inequities in retention and promotion of psychiatric faculty at U.S. medical schools were prominent. White male psychiatrists were promoted to full professor rank at a full-professor-to-assistant-professor ratio of 0.74 (13). For White women, the ratio lagged far behind at 0.26, similar to Black men at 0.24. For BIPOC women, the full-professor-to-assistant-professor ratio was 0.14, and, concerningly, the ratio for Black women was 0.08. A similar imbalance is seen at the highest levels of leadership, with White males comprising 61% of psychiatry department chairs, compared with 17% for White women, 3.9% for Latino men, 1.9% each for Latina women and Black women, and 0.6% for Black men. Finally, there is an absence of mentors and sponsors who can identify meaningful roles and advise DEI leaders on how to reduce less rewarding tasks and successfully advance in academia. Frequently, their work is devalued, which contributes to isolation and burnout (14).

Minority Tax

Because of the limited numbers of BIPOC women in psychiatry faculty positions, many DEI leaders face isolation, excessive time burdens, and additional “taxes” on their time. This double minority tax (gender and racial/ethnic underrepresentation in medicine) limits their ability to be effective (2). In order to demonstrate institutional diversity, BIPOC faculty are frequently asked to serve on committees, liaise with community groups, and mentor students, but such work is not compensated or part of promotional activities (15). DEI leaders are also often asked to oversee cultural humility and antiracism courses and serve as “supermentors” of trainees, also uncompensated. This results in unique harms, including decreased pay, uncompensated labor, and scholarship that is not recognized or is devalued, resulting in moral injury.

Family Caregiving Responsibilities

A large proportion of our DEI leader sample are also mothers, informal caregivers, and/or provide financial support to extended family members (common for BIPOC women earners [16]), exemplifying both the vulnerability and the resilience of these leaders. Studies have shown that physician mothers experience discrimination at work and are at risk for burnout and mental health issues (4, 8).

Essential Community Support Needed for DEI Leadership

To consider next steps in alleviating the challenges facing BIPOC women in DEI positions within psychiatry, a small group of DEI leaders convened at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in San Francisco in May 2019. DEI leaders shared common concerns and challenges. The group agreed to meet regularly for support, scholarship, and the promotion of equity in academic medicine. This group not only provides a space for sharing lived experience but also offers a respite for the trauma endured by oppressive structures within academic psychiatry. The space is liberating in that it allows BIPOC DEI leaders to speak openly about hurtful, discriminatory experiences without feeling forced, as they do in other settings, to minimize the impact of these experiences. In short, this is a place for disagreement, tears, support, and processing of sexist and/or racist experiences.

Additionally, this group provides critical peer mentorship through sharing of different institutional cultures and the ingredients for success and pitfalls in leading diversity efforts. Given the limited numbers of BIPOC women among senior faculty, finding mentors can be challenging. Peer support and mentorship are critical ingredients to success. In addition to mentorship, these communities provide an “old girls” network, which can lead to an increase in sponsorship and opportunities.

Supporting BIPOC Women in DEI Leadership in the Face of Two Pandemics

As our nation faces two national pandemics—COVID-19 and racism—we believe this is the ideal time to reenvision DEI leadership positions in psychiatry. During the COVID-19 pandemic, women are at risk for adverse psychological impacts, and early evidence shows productivity declines among women in academia (17–19). The financial toll of the COVID-19 pandemic has also resulted in heightened stress for many DEI leaders who are the primary breadwinners in their household. Although the increased attention that has been given to structural racism is an outstanding step forward for our country, the case vignette exemplifies the rush to quickly address long-standing and complex racial inequities, with departments hastily creating DEI positions only to check a box as having “done something” (4). Such performative responses may set up new DEI leaders for failure, and may thus provide fodder later for claims that DEI efforts were not effective. Furthermore, research shows that leaders point to the existence of DEI structures as proof that there is equity and fairness, while ignoring information about continued discrimination—despite the necessity for white people with institutional power to address structural racism (15).

As DEI leaders at major psychiatry departments across the country, we have thrived in academia not despite but because we are BIPOC women, mothers, informal caregivers, and breadwinners. In this piece we intentionally highlighted the intersectional experiences of women in diversity roles. In addition to being from two historically excluded groups (gender and racial/ethnic minorities), many of us hold responsibilities in our households that have an impact our leadership roles. This focus was necessary, given how little emphasis is placed on the experience of women in leadership roles, especially those from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds. We do think, however, that understanding the male perspective is an area worth pursuing in the future, as data on these experiences will likely provide a valuable comparison.

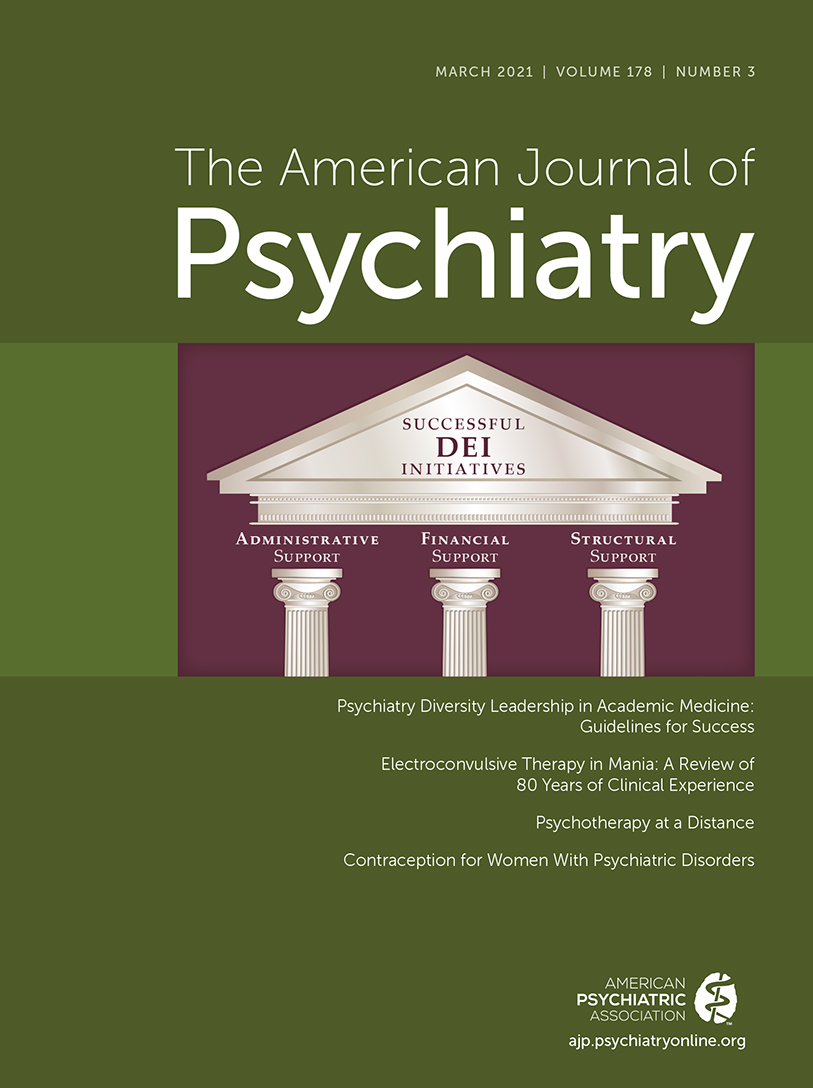

In conclusion, DEI efforts should not be isolated from the power structures within a department, but instead should be integrated into the highest levels of decision making to ensure a presence and active voice in any setting where real power is wielded. Box 1 provides recommendations for the necessary support for the success of DEI leadership. Only through adequate financial, administrative, and structural support can inclusive excellence begin to be infused into all departmental activities.

BOX 1. Best practices to effectively support psychiatry Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) leadership efforts

Structural Changes to Recognize DEI Commitment

Title: Vice or associate chair in the department, a strategic elevation of the role to clearly state the importance of the role.

Leadership team: Departmental cabinet and/or executive committee membership.

Endowed chair: Strongly consider a named endowed chair to afford academic prestige and the financial support/stability that the position deserves.

Financial Support

Salary support: This is critical, with an ideal range of 25%–100%, reflective of effort, with very explicit management of expectations given effort. Funding via a named endowed chair would ensure stability of support.

Discretionary funds: DEI leaders will require discretionary support for implementation of policies, amounting to at least $50,000, renewed annually.

Staff: A full-time administrative assistant and/or program manager is critical for this role. In addition, we recommend at least 10% time for a data analyst, as structural accountability requires data management and infrastructure.

The Role

Job description: The roles and responsibilities of the DEI position should be clear when the position is first presented to potential candidates, with responsibilities commensurate with financial effort provided.

Reporting structure: We recommend dual reporting to both the department chair and the DEI leader of the School of Medicine’s Dean’s Office (or the hospital/institution).

Diversity committee: Create a diversity committee, led by the DEI leader, that includes members that represent missions across the department. These members should ideally be diverse in terms of race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, site, and role (faculty, trainee, staff). This committee will implement the majority of the work under the vision of the DEI leader.

Selection: The selection should follow current departmental process for all vice chairs at the institution (which should be an internal [or external] searched position with a search committee reflective of the diversity of the department). Selection of DEI leaders should not be held to higher standards than for other vice chairs.

Professional development: The DEI leadership position is complex and requires leadership skills training. The discretionary funds should be allowed to be used for professional development activities for the DEI leader.

Evaluation: As with all leaders, we recommend term limits for this role (20). We recommend evaluation at 5 years, with a 10-year maximum term. Evaluation of the leader should follow the current departmental processes for all other vice chairs at the institution.

Overall Considerations

All DEI decisions, actions, and statements should come jointly from the department chair and the DEI leader (and ideally the entire executive committee leadership), to avoid scapegoating and to ensure accountability of the entire leadership team.

Inclusive excellence should be part of the breath and heartbeat of the entire department. It should be woven throughout the clinical, research, and educational missions.

DEI leaders thrive with peer communities. Chairs should intentionally connect their DEI leaders to university and national DEI communities for support and sharing of best practices.

1 : Making the difference: applying a logic of diversity. Acad Manage Perspect 2007; 21:6–20Crossref, Google Scholar

2 : A piece of my mind: medical education and the minority tax. JAMA 2017; 317:1833–1834Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 : Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ 2015; 15:6Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 : Diversity, equity, and inclusion that matter. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:e25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 : Structural racism is why I’m leaving organized psychiatry.

6 : Why Black doctors like me are leaving faculty positions in academic medical centers.

7

8 : Through the Labyrinth: The Truth About How Women Become Leaders. Boston, Harvard Business School Publishing, 2007Google Scholar

9 : Women discussing their differences: a promising trend. Diversity Factor 2004; 12(3):22–29Google Scholar

10 : Women and women of color in leadership: complexity, identity, and intersectionality. Am Psychol 2010; 65:171–181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 : Conducted monotones to coacted harmonies: a feminist (re)conceptualization of leadership addressing race, class, and gender, in Women and Leadership: Transforming Visions and Diverse Voices. Edited by Chin JL, Lott B, Rice JK, . Malden, Mass, Blackwell, 2007, pp 35–54Crossref, Google Scholar

12 At the crossroads of race and gender: lessons from the mentoring experiences of professional Black women, in Mentoring Dilemmas: Developmental Relationships Within Multicultural Organizations. Edited by Murrell AJ, Crosby FJ, Ely RJ. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1999, pp 83–104Google Scholar

13

14 : Burnout among medical school faculty. Analysis in Brief 2019; 19(1):1–3 (https://archives.pdx.edu/ds/psu/27840)Google Scholar

15 : “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med 2013; 88:405–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 : Intersectionality and family-friendly policies in the federal government: perceptions of women of color. Adm Soc 2017; 49:105–120Crossref, Google Scholar

17 : Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e203976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 : Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nat Hum Behav 2020; 4:880–883Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 : COVID-19 medical papers have fewer women first authors than expected. eLife 2020; 9:e58807Crossref, Google Scholar

20 : Unplugging the pipeline: a call for term limits in academic medicine. N Engl J Med 2019; 381:1508–1511Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar