Addressing the Homeless Mentally Ill in San Francisco

San Francisco has long taken a compassionate approach to the homeless mentally ill. San Francisco was the first city to implement the Housing First model. The city offers a broad array of mental health and substance use disorder services, and it has pioneered programs that offer treatment in lieu of incarceration. In 2016, under the leadership of the late Mayor Ed Lee, the city took another step forward and consolidated its homelessness and supportive housing services under one department, guided by a strategic plan that seeks to solve homelessness based on individual needs. The city also participates in the state’s Whole Person Care pilot program through the state’s Medicaid program, and it is piloting the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion program, which offers voluntary treatment and services as an alternative to arrest.

Yet, despite these efforts and significant resource investments, we see on our streets a group of people who are triply diagnosed with medical/surgical/psychiatric illness, often with concurrent substance use disorder, unable to function or live outside of a structured care setting. California law allows people who meet criteria for “grave disability”—defined as an inability to feed, shelter, or clothe oneself—to be placed under conservatorships overseen by the county. Conservatorships may last up to 1 year, during which time the county provides for the individual’s basic needs, medical care, and social supports through intensive case management. Unfortunately, the law does not include a history of substance use disorder as a criterion for meeting grave disability. Mayor Lee’s hope was to fix the system so that we would have the resources to care humanely for the seriously mentally ill, exactly as our medical-surgical colleagues do for serious medical illness.

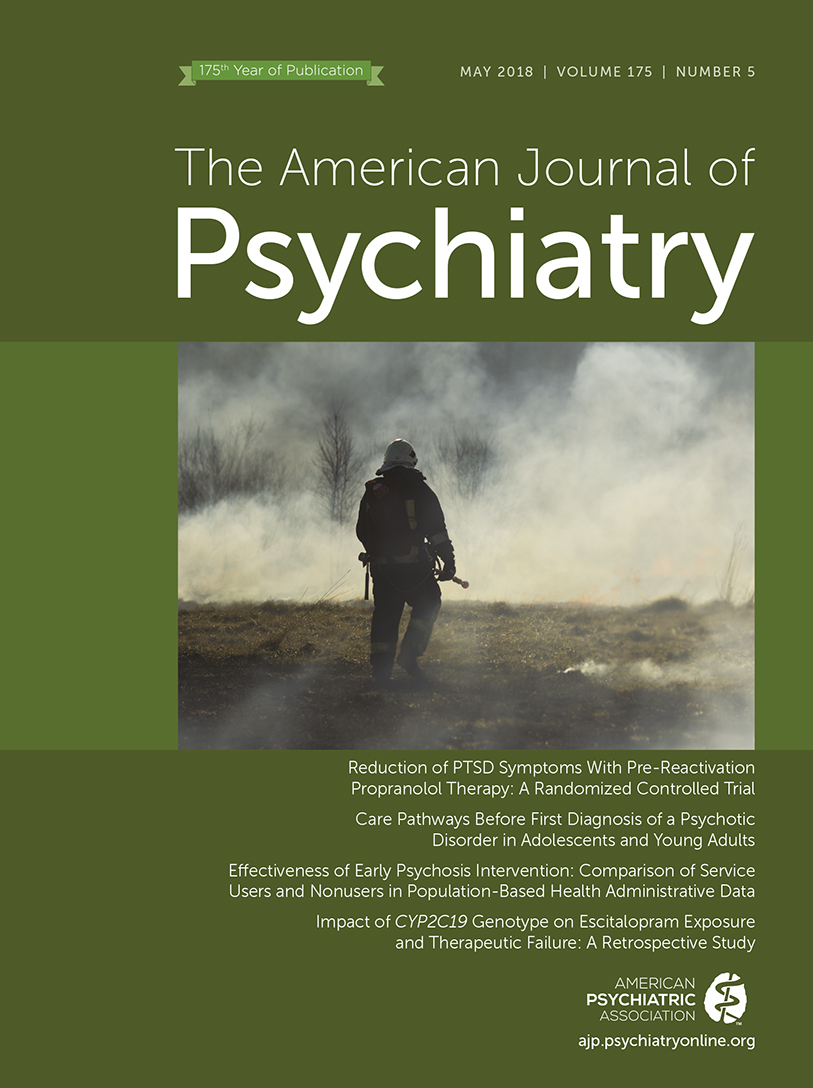

A homeless man on the streets of San Francisco who acknowledged that he had been treated for a serious mental illness. Photograph by Dr. Glick.