Association of Pre-Onset Cannabis, Alcohol, and Tobacco Use With Age at Onset of Prodrome and Age at Onset of Psychosis in First-Episode Patients

Abstract

Objective: Several reports suggest that cannabis use is associated with an earlier age at onset of psychosis, although not all studies have operationalized cannabis use as occurring prior to onset of symptoms. This study addressed whether pre-onset cannabis use, alcohol use, and tobacco use are associated with an earlier age at onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms. Effects of the progression of frequency of use were examined through time-dependent covariates in survival analyses. Method: First-episode patients (N=109) hospitalized in three public-sector inpatient psychiatric units underwent in-depth cross-sectional retrospective assessments. Prior substance use and ages at onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms were determined by standardized methods, and analyses were conducted using Cox regression modeling. Results: Whereas classifying participants according to maximum frequency of use prior to onset (none, ever, weekly, or daily) revealed no significant effects of cannabis or tobacco use on risk of onset, analysis of change in frequency of use prior to onset indicated that progression to daily cannabis and tobacco use was associated with an increased risk of onset of psychotic symptoms. Similar or even stronger effects were observed when onset of illness or prodromal symptoms was the outcome. A gender-by-daily-cannabis-use interaction was observed; progression to daily use resulted in a much larger increased relative risk of onset of psychosis in females than in males. Conclusions: Pre-onset cannabis use may hasten the onset of psychotic as well as prodromal symptoms. Age at onset is a key prognostic factor in schizophrenia, and discovering modifiable predictors of age at onset is crucial.

Cannabis is the most abused illicit substance among individuals with schizophrenia (1 , 2) . Data from 53 treatment studies involving schizophrenia patients revealed that 12-month prevalence estimates of use and misuse of cannabis were 29% and 19%, respectively, and lifetime use and misuse estimates were 42% and 23%, respectively (3) . In patients with first-episode psychosis, reported rates of cannabis misuse have ranged from 15% to 65% (3 – 11) , rates of alcohol misuse from 27% to 43% (9 , 11 – 15) , and rates of daily cigarette smoking from 50% to 75% (11 , 13 , 16) . Many studies of first-episode patients demonstrate that initiation of substance use typically precedes onset of psychosis, often by several years (4 , 17 – 19) . This is true of cannabis use in particular (1 , 20) . Although it is less clear how often substance abuse precedes onset of the prodrome, two studies found that substance abuse occurs pre-prodromally in 28%–34% of cases (21 , 22) .

At least seven published studies, of variable methodological rigor, suggest that pre-onset cannabis use may be associated with an earlier age at onset of psychosis, which is critically important given the adverse prognostic implications of earlier onset. A study of 232 first-episode patients (21) found that the mean ages at onset of the first sign, first negative symptom, first positive symptom, and first admission were lower in the 32% who had abused drugs prior to admission than in those who had not. A study of 541 first-episode patients (4) found that female patients with moderate to severe substance use at admission had an earlier onset than those with no history of substance misuse; however, the study included patients with affective psychoses, who would be expected to have a later age at onset and a lower prevalence of comorbid cannabis use. In a third study (12) , 82 of 357 patients who used cannabis with or without alcohol had an earlier onset than nonusers or those who used alcohol alone or with other drugs. In an incidence study of 133 patients (22) , those using cannabis (N=70) had an earlier median age at first psychotic episode than those who did not use cannabis (N=63); male cannabis users had their first psychotic episode on average 6.9 years earlier than male nonusers, and cannabis use was a stronger predictor of age at first psychotic episode than gender. In a retrospective study (19) , 79 first-episode patients abusing cannabis had an earlier onset compared with 186 who did not use cannabis, although this study evidently did not control for the influence of gender, and only 18% of female patients used substances, compared with 44% of male patients. In a study of 152 first-episode patients (9) , those reporting past substance use were significantly younger at onset of psychotic symptoms than those who had not used substances. Gender and cannabis use, but not use of other substances, were significantly related to age at onset, which was on average 4.2 years younger for men and 5.0 years younger for patients using cannabis, adjusting for other variables. In a study of 131 first-episode patients (23) , a gradual reduction in age at onset was observed as the level of misuse of cannabis increased—a decrement of 7, 8.5, and 12 years for patients with cannabis use, abuse, and dependence, respectively—and the effect was not explained by use of other drugs or gender. However, the study included patients with affective psychoses, who, as noted above, are likely to have both a lower prevalence of comorbid cannabis use and a later onset.

While these studies suggest but do not confirm that pre-onset cannabis use may be associated with a younger age at onset of psychotic symptoms, it remains largely unknown whether cannabis use is associated with a younger age at onset of prodromal symptoms. In fact, one critique of the literature is that the possible influence of cannabis use on prodromal symptoms has not been explored (9) . Furthermore, in several of the aforementioned studies (9 , 12 , 21 , 23) , it is unclear whether the operationalization of cannabis use ensured that such use occurred prior to onset of symptoms, which is a crucial distinction in proving a potential effect of cannabis use in hastening onset.

In this study, we assessed whether cannabis use, as well as alcohol and tobacco use, occurring prior to onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms is associated with an earlier age at onset of such symptoms. Additionally, unlike prior studies, such effects were examined further by incorporating the level of frequency of use prior to onset as a time-dependent covariate in the analysis of time to onset of symptoms. Finally, we examined these relationships in a sample of urban, predominantly minority patients. Previous studies have shown that socially disadvantaged ethnic minority groups have substantially higher rates of cannabis use and psychosis than other populations (24 – 27) .

Method

Participants

Participants (N=109) were recruited from among patients admitted to two psychiatric units of an urban, university-affiliated, public-sector hospital (N=99) or an urban county psychiatric crisis center (N=10) for an initial manifestation of nonaffective psychosis. The community served by these inpatient units is socially disadvantaged (e.g., low-income) and predominantly African American. English-speaking patients 18–40 years of age were eligible. Exclusion criteria were mental retardation, a Mini-Mental State Examination (28) score <23 (which would indicate disorientation or cognitive impairment to an extent that could interfere with the extensive clinical research assessment), a significant medical condition compromising ability to participate, prior treatment for psychosis lasting >3 months, previous hospitalization for psychosis >3 months before the index hospitalization, and inability to provide informed consent. The study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board, the Grady Health System Research Oversight Committee, and the Georgia Department of Human Resources Institutional Review Board.

Diagnoses were determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (29) . Primary psychosis diagnoses among the 109 patients were as follows: 62 patients (56.9%) with schizophrenia, 22 (20.2%) with schizophreniform disorder, eight (7.3%) with schizoaffective disorder, 12 (11.0%) with psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, four (3.7%) with brief psychotic disorder, and one (0.9%) with delusional disorder.

Assessments

The SCID-I was used for diagnosing substance use disorders in addition to primary psychotic disorders. All obtainable data were used, including interviews, data from chart reviews, and collateral interviews with family members or other informants when available. Data on substance use were collected by inquiring about use at three levels of frequency—ever, weekly, and daily—for cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco. The corresponding age at which each level of frequency of use began was also recorded for each substance. Data were collected as part of a larger clinical research assessment after rapport had been established, in a nonjudgmental manner, using a structured interview.

Ages at onset of prodrome and psychosis were determined using the Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia inventory (30) and complementary items from the semistructured Course of Onset and Relapse Schedule/Topography of Psychotic Episode interview (31) . The Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia inventory has demonstrated good to excellent interrater reliability for the presence of each symptom and duration, as well as good agreement for length of time from initial symptom onset to first treatment contact, between clinicians and patients and between clinicians and family members (30) . Given the complexities of obtaining exact dates of prodromal and psychotic onsets (32) , conventions were used to enhance the accuracy of dating (e.g., cross-referencing with life milestones). Onset of the prodrome was operationalized as the date of onset of the first-occurring of 14 possible prodromal symptoms defined by the Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia inventory. Onset of psychosis was operationalized as the date on which hallucinations or delusions were estimated to have first met the threshold of a score of 3 on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (33) . Thirty-three patients (30.3%) had no evidence of a retrospectively identifiable prodrome prior to onset of psychotic symptoms. For those patients, in the prodrome-related analyses, age at onset of psychosis was used rather than age at onset of the prodrome; thus, the term “age at onset of symptoms” is also used below.

Data Analysis

Onset and escalation of cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco use were assessed with basic descriptive statistics before the main research questions were addressed. Analyses assumed that consumption did not regress; that is, once any given frequency of use (e.g., weekly) occurred, it was assumed to have continued beyond that age until a higher level of frequency occurred or until onset of prodromal or psychotic symptoms. Although the data set did not have the granularity needed to indicate potential decreases in use over time, it did allow for an assessment of progression of use, enabling analyses using time-dependent variables. Moreover, extensive clinical experience with the population of interest suggests that decreased use over time after a given level of use has developed is rare during the years (typically adolescence) preceding onset .

Two sets of analyses were conducted. First, similar to prior studies, patients were classified according to their substance use. Unlike in most prior studies, however, participants were classified according to their frequency of use, and it was verified that this use was in fact prior to onset. This resulted in each patient having a maximum use level (none, ever, weekly, daily) for each type of substance (cannabis, alcohol, tobacco) before onset of symptoms. Second, because the first classification does not incorporate each patient’s use pattern prior to onset (e.g., some patients progressed quickly to daily use, while others took several years), use level (none, ever, weekly, daily) was coded as a time-dependent covariate in survival analyses. This was done to further test whether the progression or increasing severity of use had a significant effect on time to onset of symptoms. The time-dependent covariate was represented by repeated observations within participants that indicate the progression of each type of substance use from birth to age at onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms.

We used Cox regression analysis to model the effects of level of use (both fixed and time-dependent) on time to onset in years; in both cases nonusers were the reference category and frequency of use (ever, weekly, daily) was a categorical predictor. Tests of the proportional hazards assumption were performed for each model to verify the model assumptions (34) . Examination of gender and family history of psychosis as possible moderators of any observed effects was planned, but family history in first-degree relatives was present in only 13.4% of participants, making it difficult to estimate those effects with any reasonable certainty. Thus, only analyses concerning gender are presented, in which the reference category was female nonusers.

Results

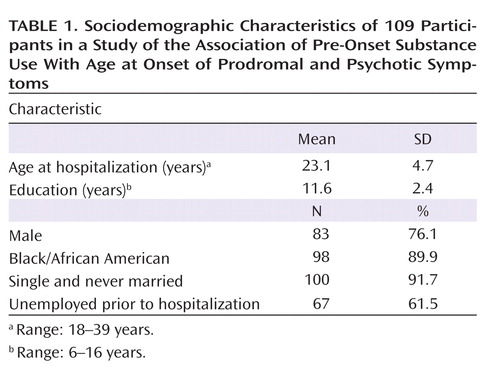

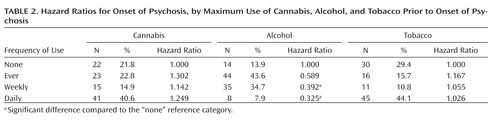

The participants’ sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1 . Mean ages at first-ever use, initiation of weekly use, and onset of daily use of cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco have been described previously (11) . Assessment of the maximum reported frequency of substance use prior to onset of psychosis showed a large percentage of daily cannabis users (40.6%) and daily tobacco users (44.1%) but relatively few daily alcohol users (7.9%) ( Table 2 ). The maximum reported frequency classification (prior to onset of psychosis) was highly associated with current SCID-I diagnoses of abuse and dependence for both cannabis and alcohol. For example, of those with cannabis abuse, 88% were classified as weekly (43.8%) or daily (43.8%) users prior to onset of psychosis, while of those with cannabis dependence, 90% were classified as weekly (7.5%) or daily users (82.5%) prior to onset.

Cox regression analysis with participants classified according to maximum frequency of use prior to onset (none, ever, weekly, or daily) indicated no significant effects of cannabis or tobacco use on risk of onset of psychotic symptoms but showed an effect of weekly and daily alcohol use on age at onset of psychosis ( Table 2 ). Those who used alcohol weekly or daily prior to onset had a later age at onset of psychosis than those who never used alcohol prior to onset.

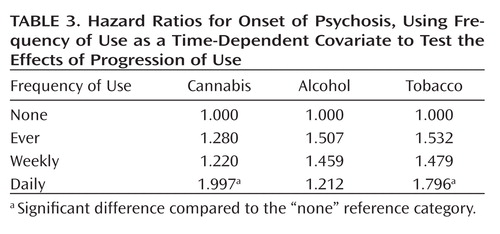

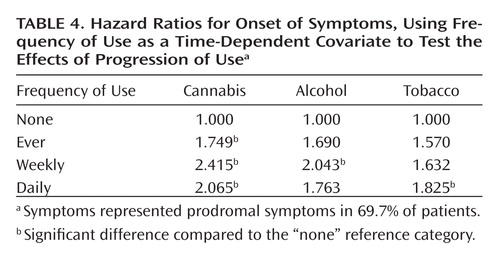

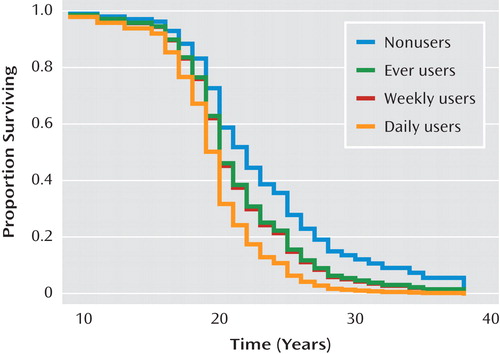

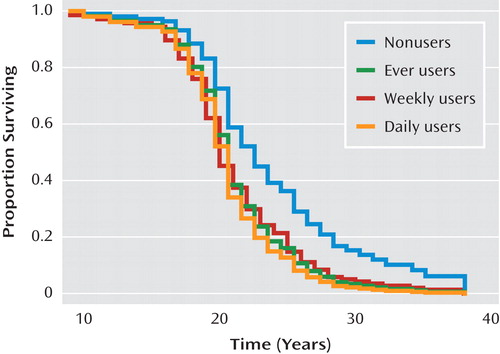

A quite different pattern was observed when examining changes in use over time (using time-dependent covariates) as a predictor of time to onset. Significant effects of progression to both daily cannabis use and daily tobacco use on risk of onset of psychosis were observed, while progression of alcohol use had no significant effect ( Table 3 ). Predicted survival curves based on Cox regression, with cannabis and tobacco use as time-dependent covariates, are shown in Figures 1 and 2 . These effects were even stronger when onset of symptoms, which represented onset of prodromal symptoms in 69.7% of patients, was used as the endpoint ( Table 4 ) instead of onset of psychosis. Additionally, a significant effect of an increase to weekly alcohol use was observed for the onset of prodromal symptoms; the daily use category showed a slight decrease in the expected relative risk compared to the weekly category; however, this estimate is based on very few observations (2.5%), so the difference is likely unremarkable.

a Based on Cox regression, with cannabis use as a time-dependent covariate. “Proportion surviving” refers to the proportion of participants free of psychosis or not yet having onset of psychotic symptoms.

a Based on Cox regression, with cannabis use as a time-dependent covariate. “Proportion surviving” refers to the proportion of participants free of psychosis or not yet having onset of psychotic symptoms.

Gender was assessed as a potential moderator of the effects of progression of substance use on age at onset of psychosis. Because only 24% of participants were female, similar relative risk categories (ever and weekly use) were collapsed before testing for a gender difference in the relationship between progression of prior substance use and onset of psychosis. The only type of substance use that exhibited a gender-by-progression-of-frequency-of-use interaction was daily cannabis use (z=–1.92, p=0.054), such that progression to daily use was associated with a larger increased relative risk for onset of psychosis in female patients (hazard ratio=5.154) than in male patients (hazard ratio=3.359). That is, male patients with no history of use and those with ever or weekly use had higher hazard ratios than the female comparison groups (2.250 compared with 1.000, and 2.329 compared with 2.049, respectively), which was expected, although the male and female patients were not significantly different at those levels. However, for daily users, the hazard ratio was 3.359, compared with 5.154, indicating a reversal of the pattern of findings (higher in female patients).

Discussion

Several noteworthy findings emerged from this analysis of a relatively large, well-characterized sample of socially disadvantaged, predominantly African American, first-episode psychosis patients. First, as reported previously (11) , rates of substance use, and cannabis use in particular, were remarkably high. This, and the fact that use of other substances was relatively rare in this sample, provides an ideal opportunity to examine the relations of pre-onset cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco use with age at onset. Second, and particularly interesting, in contrast to prior reports, analyses of frequency and changes in frequency indicate that risk of onset was not associated with simple classifications of use or frequency of use but with progression of use prior to onset. Third, similar or stronger effects were observed when onset of prodrome or symptoms was used as the endpoint, which is of importance in clarifying temporality. Fourth, a gender-by-progression-to-daily-cannabis-use interaction was observed, such that progression to daily use increased the relative risk of onset of psychosis more in females than in males. Rapid progression to the highest levels of use (especially tobacco and cannabis use, which are highly prevalent in this population) is associated with an increased risk of onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms.

Clear inferences about the role of cannabis use in hastening the onset of psychosis have not been possible to date. The present findings extend the literature by limiting analyses to cases of nonaffective psychosis and only considering substance use began prior to the emergence of symptoms. Furthermore, whereas most past analyses have dichotomized subjects by use/nonuse or by presence or absence of a substance use disorder, in this study we accounted for frequency and escalation of use over time. Although an interesting association between cannabis use and age at onset of psychotic symptoms was revealed, this is an association, not a demonstration of causality; increased use of cannabis by those imminently approaching the onset of psychotic symptoms is also a reasonable interpretation of these data.

These analyses augment prior studies by demonstrating a possible effect of pre-onset cannabis (and tobacco) use on age at onset of symptoms or prodrome. The prodrome, now studied extensively using both retrospective and prospective designs (35 , 36) , is emerging as a potential syndromal therapeutic target in indicated preventive interventions using both psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic modalities. This study suggests that other modalities—including prevention, early identification, and treatment of cannabis use—may delay onset in clinical high-risk samples.

Although these results cannot establish a mechanism by which increasing cannabis use is associated with earlier onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms, accumulating research on the cannabinoid system suggests biological plausibility. Exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids exert their effects (such as modulating release of neurotransmitters including glutamate, norepinephrine, and dopamine) through specific cannabinoid (CB1) receptors (37 , 38) distributed in brain regions implicated in schizophrenia (39) . Several studies show increased CB1 receptor density in regions of interest in schizophrenia (40 – 42) , as well as elevated levels of endogenous cannabinoids in blood and CSF of patients (43 – 45) . These findings, in addition to studies showing that acute administration of cannabis causes both patients and comparison subjects to experience transient worsening of cognition and schizophrenia-like positive and negative symptoms (46 , 47) , add to arguments for biological plausibility. From an epidemiological perspective, growing evidence implicates cannabis use as a component cause or independent risk factor for psychotic symptoms and psychotic disorders (48) , and some evidence indicates that earlier or heavier use is associated with greater risk (49) .

Several findings require confirmation before clear mechanisms can be established. First, this study suggests an interaction whereby progression to daily use may lead to a larger increased relative risk for onset of psychosis in female than in male patients. Similar findings were observed in a sample of 541 patients with first-episode affective or nonaffective psychoses (4) . If this finding is further replicated, it may be similar to the observation that gender effects on age at onset of psychosis are overridden by competing risks, such as family history of psychosis (that is, family history has a more powerful impact on age at onset in female patients, potentially overriding the effects of gender) (50) . The gender effect on age at onset may be reversed in the context of heavy pre-onset cannabis use. Such findings could be driven by differences in other exposures or differences in neurodevelopmental trajectories across genders. Alternatively, the later age at onset typically observed in females could lengthen the duration of pre-onset exposure to cannabis, effectively increasing the window of opportunity for cannabis to affect age at onset. Second, the apparent equally strong relationship between nicotine use and onset is difficult to interpret given the level of concordance between cannabis and nicotine use. However, despite remarkably high rates of cigarette smoking in schizophrenia, there is little evidence supporting nicotine as a component cause for psychotic symptoms or psychotic disorders. Nonetheless, extensive research documents links between nicotinic cholinergic neurotransmission and schizophrenia (51) . Although effects of nicotine on cognition are thought to be most pertinent, affected individuals also may smoke to regulate mood and reduce stress (52) . However, abnormal neurotransmission in the nicotinic system potentially could contribute to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (51) .

These results should be interpreted in light of several methodological limitations. First, the representativeness and generalizability of our findings is limited given the sample’s specific sociodemographic characteristics. However, the documented high prevalence of pre-onset substance use suggests that this population may be ideal for answering these and related research questions. Second, parsing the independent effects of individual substances (e.g., cannabis and tobacco) requires larger sample sizes. However, pre-onset use of other substances (e.g., methamphetamine, hallucinogens) is rare in this population, indicating that uncovering independent effects of cannabis may indeed be possible in future studies. Third, an inherent limitation is the difficultly in retrospectively measuring ages at onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms, as well as ages at first, weekly, and daily use of substances. Standardized methods were used to provide the most accurate data possible. Regarding age at onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms, the investigative team is well versed in the measurement of symptom onset (32) ; the Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia inventory and selected items from the Course of Onset and Relapse Schedule/Topography of Psychotic Episode interview were deemed the most rigorous and psychometrically sound, yet practical and user-friendly, method for estimating onset dates. Because of the lack of appropriate instruments assessing ages at which each level of frequency of use began, this study relied on a structured interview, although the reliability and validity of substance use data collected in this manner cannot be determined. However, retrospective self-report is the most frequently used method of data collection for past substance use over a specified time interval. Despite known limitations, a substantial body of research supports the utility of thorough retrospective self-report measurement of substance use (53 , 54) .

The present findings expand an accumulating literature suggesting that pre-onset substance use, especially cannabis use, may have a significant effect in hastening onset of psychotic, and now prodromal, symptoms among first-episode patients. Given the well-established finding that age at onset is a key prognostic factor in schizophrenia, discovering a modifiable predictor of age at onset has important implications. Earlier onset generally results in greater cognitive impairment, increased severity of functional disability, more severe symptoms and behavioral deterioration, less responsiveness to antipsychotics, and greater likelihood of rehospitalization (55 , 56) . Thus, delaying onset by reducing adolescent pre-onset substance use could result in substantial improvements in outcomes. As early psychosis research advances toward identifying potentially prodromal adolescents and young adults prior to onset of psychosis, targeted interventions could include curbing substance use, in addition to psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions targeting prodromal symptoms. Such interventions may delay onset of psychosis, perhaps averting it altogether, given that cannabis use in adolescence is increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for psychosis and schizophrenia (57) .

1. Linszen DH, Dingemans PM, Lenior ME: Cannabis abuse and the course of recent-onset schizophrenic disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:273–279Google Scholar

2. Bersani G, Orlandi V, Kotzalidis GD, Pancheri P: Cannabis and schizophrenia: impact on onset, course, psychopathology, and outcomes. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002; 252:86–92Google Scholar

3. Green B, Young R, Kavanagh D: Cannabis use and misuse prevalence among people with psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 187:306–313Google Scholar

4. Rabinowitz J, Bromet EJ, Lavelle J, Carlson G, Kovasznay B, Schwartz JE: Prevalence and severity of substance use disorder and onset of psychosis in first-admission psychotic patients. Psychol Med 1998; 28:1411–1419Google Scholar

5. Cantwell R, Brewin J, Glazebrook C, Dalkin T, Fox R, Medley I, Harrison G: Prevalence of substance misuse in first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:150–153Google Scholar

6. Hambrecht M, Häfner H: Cannabis, vulnerability, and the onset of schizophrenia: an epidemiological perspective. Austr N Z J Psychiatry 2000; 34:468–475Google Scholar

7. Addington J, Addington D: Impact of an early psychosis program on substance use. Psychiatr Rehab J 2001; 25:60–68Google Scholar

8. Compton MT, Furman AC, Kaslow NJ: Lower negative symptom scores among cannabis-dependent patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: preliminary evidence from an African American first-episode sample. Schizophr Res 2004; 71:61–64Google Scholar

9. Barnes TRE, Mutsatsa SH, Hutton SB, Watt HC, Joyce EM: Comorbid substance use and age at onset of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2006; 188:237–242Google Scholar

10. Wade D, Harrigan S, Edwards J, Burgess PM, Whelan G, McGorry PD: Course of substance misuse and daily tobacco use in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 2006; 81:145–150Google Scholar

11. Stewart T, Goulding SM, Esterberg ML, Pringle M, Compton MT: A descriptive study of nicotine, alcohol, and cannabis use in urban, socially-disadvantaged, predominantly African American patients with first-episode nonaffective psychosis. Clinical Schizophrenia and Related Psychoses (in press)Google Scholar

12. Van Mastrigt S, Addington J, Addington D: Substance misuse at presentation to an early psychosis program. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2004; 39:69–72Google Scholar

13. Wade D, Harrigan S, Edwards J, Burgess PM, Whelan G, McGorry PD: Patterns and predictors of substance use and daily tobacco use in first-episode psychosis. Austr N Z J Psychiatry 2005; 39:892–898Google Scholar

14. Addington J, Addington D: Patterns, predictors, and impact of substance use in early psychosis: a longitudinal study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007; 115:304–309Google Scholar

15. Barnett JH, Werners U, Secher SM, Hill KE, Brazil R, Masson K, Pernet DE, Kirkbride JB, Murray GK, Bullmore ET, Jones PB: Substance use in a population-based clinic sample of people with first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2007; 190:515–520Google Scholar

16. Harrison I, Joyce EM, Mutsatsa SH, Hutton SB, Huddy V, Kapasi M, Barnes TR: Naturalistic follow-up of co-morbid substance use in schizophrenia: the West London first-episode study. Psychol Med 2008; 38:79–88Google Scholar

17. Silver H, Abboud E: Drug abuse in schizophrenia: comparison of patients who began drug abuse before their first admission with those who began abusing drugs after their first admission. Schizophr Res 1994; 13:57–63Google Scholar

18. Bühler B, Hambrecht M, Löffler W, an der Heiden W, Häfner H: Precipitation and determination of the onset and course of schizophrenia by substance abuse: a retrospective and prospective study of 232 population-based first illness episodes. Schizophr Res 2002; 54:243–251Google Scholar

19. Mauri M, Volonteri L, De Gaspari I, Colasanti A, Brambilla M, Cerruti L: Substance abuse in first-episode schizophrenic patients: a retrospective study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2006; 2:1–8Google Scholar

20. Allebeck P, Adamsson C, Engstrom A, Rydberg U: Cannabis and schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of cases treated in Stockholm County. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 88:21–24Google Scholar

21. Hambrecht M, Häfner H: Substance abuse and the onset of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:1155–1163Google Scholar

22. Veen ND, Selten J-P, van der Tweel I, Feller WG, Hoek HW, Kahn RS: Cannabis use and age at onset of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:501–506Google Scholar

23. González-Pinto A, Vega P, Ibáñez B, Mosquera F, Barbeito S, Gutiérrez M, Ruiz de Azúa S, Ruiz I, Vieta E: Impact of cannabis and other drugs on age at onset of psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69:1210–1216Google Scholar

24. King M, Coker E, Leavey G, Hoare A, Johnson-Sabine E: Incidence of psychotic illness in London: comparison of ethnic groups. Br Med J 1994; 309:1115–1119Google Scholar

25. Van Os J, Castle DJ, Takei N, Der G, Murray RM: Psychotic illness in ethnic minorities: clarification from the 1991 census. Psychol Med 1996; 26:205–210Google Scholar

26. Sharpley MS, Hutchinson G, Murray RM, KcKenzie K: Understanding the excess of psychosis among the African-Caribbean population in England: review of current hypotheses. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:s60–s68Google Scholar

27. Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD, Stinson FS: Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. JAMA 2004; 291:2114–2121Google Scholar

28. Cockrell JR, Folstein MF: Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:689–692Google Scholar

29. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1998Google Scholar

30. Perkins DO, Leserman J, Jarskog LF, Graham K, Kazmer J, Lieberman JA: Characterizing and dating the onset of symptoms in psychotic illness: the Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia (SOS) inventory. Schizophr Res 2000; 44:1–10Google Scholar

31. Norman RMG, Malla AK: Course of Onset and Relapse Schedule: Interview and Coding Instruction Guide. London, Ontario, London Health Sciences Centre, Prevention and Early Intervention for Psychosis Program, 2002Google Scholar

32. Compton MT, Carter T, Bergner E, Franz L, Stewart T, Trotman H, McGlashan TH, McGorry PD: Defining, operationalizing, and measuring the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP): advances, limitations, and future directions. Early Interv Psychiatry 2007; 1:236–250Google Scholar

33. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261–276Google Scholar

34. Grambsch PM, Therneau TM: Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994; 81:515–526Google Scholar

35. Yung AR, McGorry PD: The initial prodrome in psychosis: descriptive and qualitative aspects. Austr N Z J Psychiatry 1996; 30:587–599Google Scholar

36. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, Woods SW, Addington J, Walker E, Seidman LJ, Perkins D, Tsuang M, McGlashan T, Heinssen R: Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65:28–37Google Scholar

37. Devane WA, Dysarz FA 3rd, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Howlett AC: Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol Pharmacol 1988; 34:605–613Google Scholar

38. Iversen L: Cannabis and the brain. Brain 2003; 126:1252–1270Google Scholar

39. Ashton CH: Pharmacology and effects of cannabis: a brief review. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:101–106Google Scholar

40. Dean B, Sundram S, Bradbury R, Scarr E, Copolov D: Studies on [ 3 H]CP-55940 binding in the human central nervous system: regional specific changes in density of cannabinoid-1 receptors associated with schizophrenia and cannabis use. Neuroscience 2001; 103:9–15 Google Scholar

41. Sundram S, Dean B, Copolov D: The endogenous cannabinoid system in schizophrenia, in Marijuana and Madness: Psychiatry and Neurobiology. Edited by Castle DJ, Murray R. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp 127–141Google Scholar

42. Zavitsanou K, Garrick T, Huang XF: Selective antagonist [ 3 H]SR141716A binding to cannabinoid CB1 receptors is increased in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Progress NeuroPsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2004; 28:355–360 Google Scholar

43. Leweke FM, Giuffrida A, Wurster U, Emrich HM, Piomelli D: Elevated endogenous cannabinoids in schizophrenia. Neuroreport 1999; 10:1665–1669Google Scholar

44. De Marchi N, De Petrocellis L, Orlando P, Daniele F, Fezza F, Di Marzo V: Endocannabinoid signaling in the blood of patients with schizophrenia. Lipids Health Dis 2003; 2:5–14Google Scholar

45. Giuffrida A, Leweke FM, Gerth CW, Schreiber D, Koethe D, Faulhaber J, Klosterkötter J, Piomelli D: Cerebrospinal anandamide levels are elevated in acute schizophrenia and are inversely correlated with psychotic symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacol 2004; 29:2108–2114Google Scholar

46. Castle DJ, Solowij N: Acute and subacute psychomimetic effects of cannabis in humans, in Marijuana and Madness: Psychiatry and Neurobiology. Edited by Castle D, Murray R. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp 41–53Google Scholar

47. D’Souza DC, Abi-Saab WM, Madonick S, Forselius-Bielen K, Doersch A, Braley G, Gueorguieva R, Cooper TB, Krystal JH: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol effects in schizophrenia: implications for cognition, psychosis, and addiction. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:594–608Google Scholar

48. Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, Barnes TR, Jones PB, Burke M, Lewis G: Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 2007; 370:319–328Google Scholar

49. Arseneault L, Cannon M, Poulton R, Murray R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE: Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longitudinal prospective study. BMJ 2002; 325:1212–1213Google Scholar

50. Gorwood P, Leboyer M, Jay M, Payan C, Feingold J: Gender and age at onset in schizophrenia: impact of family history. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:208–212Google Scholar

51. Ripoll N, Bronnec M, Bourin M: Nicotinic receptors and schizophrenia. Curr Med Res Opin 2004; 20:1057–1074Google Scholar

52. Mobascher A, Winterer G: The molecular and cellular neurobiology of nicotine abuse in schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry 2008; 41(suppl 1):S51–S59Google Scholar

53. O’Farrell TH, Maisto, SA: The utility of self report and biological measures of drinking in alcoholism treatment outcome studies. Adv Behav Res Ther 1987; 9:91–125Google Scholar

54. Brown J, Kranzler HR, Del Boca FK: Self-reports by alcohol and drug abuse inpatients: factors affecting reliability and validity. Br J Addict 1992; 87:1013–1024Google Scholar

55. Jeste DV, McAdams LA, Palmer BW, Braff D, Jernigan TL, Paulsen JS, Stout JC, Symonds LL, Bailey A, Heaton RK: Relationship of neuropsychological and MRI measures to age at onset of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 98:156–164Google Scholar

56. Tuulio-Henriksson A, Partonen T, Suvisaari J, Haukka J, Lonnqvist J: Age at onset and cognitive functioning in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 185:215–219Google Scholar

57. Smit F, Boiler L, Cuijpers P: Cannabis use and the risk of later schizophrenia: a review. Addiction 2004; 99:425–430Google Scholar