Institutional Rearing and Psychiatric Disorders in Romanian Preschool Children

Abstract

Objective: There is increasing interest in the relations between adverse early experiences and subsequent psychiatric disorders. Institutional rearing is considered an adverse caregiving environment, but few studies have systematically examined its effects. This study aimed to determine whether removing young children from institutional care and placing them with foster families would reduce psychiatric morbidity at 54 months of age. Method: Young children living in institutions in Bucharest were enrolled when they were between 6 and 30 months of age. Following baseline assessment, 136 children were randomly assigned to care as usual (continued institutional care) or to removal and placement in foster care that was created as part of the study. Psychiatric disorders, symptoms, and comorbidity were examined by structured psychiatric interviews of caregivers of 52 children receiving care as usual and 59 children in foster care when the children were 54 months of age. Both groups were compared to 59 typically developing, never-institutionalized Romanian children recruited from pediatric clinics in Bucharest. Foster care was created and supported by social workers in Bucharest who received regular consultation from U.S. clinicians. Results: Children with any history of institutional rearing had more psychiatric disorders than children without such a history (53.2% versus 22.0%). Children removed from institutions and placed in foster families were less likely to have internalizing disorders than children who continued with care as usual (22.0% versus 44.2%). Boys were more symptomatic than girls regardless of their caregiving environment and, unlike girls, had no reduction in total psychiatric symptoms following foster placement. Conclusions: Institutional rearing was associated with substantial psychiatric morbidity. Removing young children from institutions and placing them in families significantly reduced internalizing disorders, although girls were significantly more responsive to this intervention than boys.

Extremes of early experience provide opportunities to explore the origins of psychopathology. In fact, the association between adverse early experiences and later psychiatric morbidity seems increasingly clear (1 – 4) . Institutional rearing, which was examined on a small scale and in often poorly controlled studies in the mid-20th century, has recently reemerged as a focus of study as tens of thousands of previously institutionalized children have been adopted into Western Europe and North America. Certain features characterize most institutional care for young children: regimented daily schedules, high ratios of children to caregivers, nonindividualized care, lack of psychological investment by caregivers, and rotating caregiver shifts, which all contribute to an adverse caregiving and social environment (5) . Not surprisingly, young children adopted out of institutions characterized by social and material deprivation have been shown to be at risk for a variety of psychiatric sequelae, such as attachment disorders (6 , 7) , attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (8 , 9) , and posttraumatic stress disorder (10) . Nevertheless, to our knowledge, adoption studies have not assessed characteristics of the preadoptive caregiving environment nor the child’s status prior to removal from an institution (11 , 12) . Both have varied in previous studies (13 – 15) . Also, children are not adopted randomly from institutions—more impaired children are less likely to be included in adoption studies. Another limitation in previous research is that measures of psychiatric morbidity have been limited, either focusing on single disorders or relying on behavior problem checklists rather than structured psychiatric interviews (7 , 8 , 10 , 16 – 18) .

As well, results from previous studies cannot adequately address the question of the role of the caregiving environment in reducing subsequent psychopathology. Young children who are institutionalized usually have a variety of genetic and prenatal risk factors that precede their placement. Despite this, many children adopted from institutions seem not to have serious psychopathology, at least when assessed several years following adoption (11 , 12) , suggesting that enhanced caregiving environments following adoption may reduce the likelihood of psychopathology. This is not surprising given the vast amount of developmental research suggesting that outcomes at particular points in development are the result of ongoing interactions between a child’s characteristics (including genetic endowment and early experiences) and the environment’s characteristics. Although not designed as a test of the transactional model of development (19) , the current study examined whether a dramatic change in caregiving environments, randomly allocated to children with significant histories of adversity, can change children’s developmental trajectories from psychopathology toward more adaptive behaviors, and it attempted to determine which characteristics in which individuals are more or less amenable to intervention. In addition, recent reviews in the developmental literature underscore the importance of early experiences in molding trajectories for psychopathology. Because the children entered the current study ranging in age from 6 to 30 months of age, we were able to examine the effects of age at which the intervention began in relation to outcome at 54 months of age, an age at which psychiatric disorders are as prevalent as they are in school-age children and adolescents (20 , 21) . Specifically, we predicted that children with a history of institutional rearing would have more psychiatric disorders and impairment than young children who had never been institutionalized. We also predicted that young children removed from institutions and placed in foster care would have fewer psychiatric disorders and symptoms and less impairment.

Method

Participants

The study was part of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (15) . The participants in this investigation were 170 children who were assessed at a mean age of 55.56 months (SD=1.92). They were derived from two groups.

Children reared in institutions

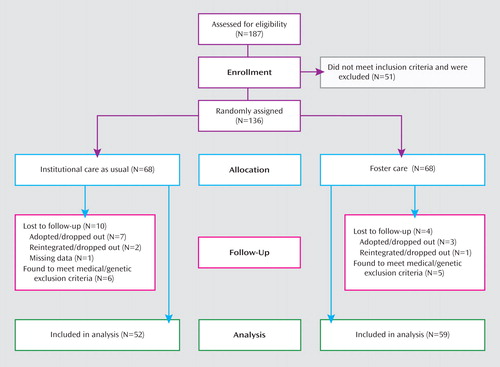

As shown in Figure 1 , we screened 187 children less than 31 months of age (range=6–30 months) who were residing in any of the six institutions for young children in Bucharest, Romania. Screening consisted of a pediatric neurologic examination, growth measurements, auditory assessment, and assessment of physical abnormalities. Of this original group, 51 children were excluded for medical reasons, including genetic syndromes, frank signs of fetal alcohol syndrome (based on facial dysmorphology), and microcephaly according to the Tanner standards (22) . Thus, the study group at baseline comprised 136 children who were living in institutions and had lived in institutions at least half of their lives. Birth records for these children were limited, and we had data on gestational age for only 112 children; the range was from 30 to 42 weeks (mean=37.2 weeks, SD=2.2). Birth weight was available for 117 children and ranged from 900 to 4,150 g (mean=2,767 g, SD=609).

Eleven of the original participants were later found to meet the original exclusion criteria involving medical and genetic disorders and were not included in the analyses (these 11 included five girls and six boys with a mean age of 18.09 months; six children remained institutionalized and five were placed in foster care). Thus, 125 institutionalized children were evaluated at baseline for purposes of the longitudinal study.

After the baseline assessment, 68 children living in institutions, 33 boys and 35 girls, were randomly assigned to receive continued institutional care. The other randomly selected 68 children in institutions, 34 boys and 34 girls, were placed in 56 foster homes supported by the study.

For the randomization procedure, each child’s name was assigned a number, and the numerals “1” through “136” were written on pieces of paper. There were two sets of twins, and for each pair the numbers for both twins were written on the same piece of paper. The pieces of paper were placed in a hat. The first number pulled out of the hat was assigned to care as usual, and the second was assigned to foster care, with assignments proceeding in the same alternating manner.

The children in the two groups were indistinguishable on age, gender, ethnicity, birth weight, developmental quotient, observed caregiving environment, caregiver ratings of behavior problems, and competence at baseline (14) .

Never-institutionalized group

An additional 72 children, 31 boys and 41 girls, were recruited from community pediatric clinics in Bucharest. They had been born at the same maternity hospitals as the abandoned, institutionalized children, were living with their biological parents, and had no history of institutional care. They did not differ in mean age or gender from the children reared in institutions. Shortly after beginning the baseline assessment, seven families chose to withdraw their children from the study (seven girls, all Romanian, mean age=21.92 months), and the final number of never-institutionalized children was 65. All fell within 2 standard deviations of the means for weight, height, and head circumference in the growth norms of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (23) . The mean birth weight of the never-institutionalized group (mean=3338 g, SD=467) was significantly greater than that of the children with a history of institutional care (mean=2767 g, SD=609) (t=6.8, df=187, p<0.001).

Over time, an additional 19 children in the never-institutionalized group dropped out of the study, with parents citing mostly time constraints or maternal employment. One child in the never-institutionalized group had an incomplete interview and was not included in the analyses. An additional 14 children, five boys and nine girls, were recruited at age 54 months from the same pediatric clinics as the original never-institutionalized group. The final never-institutionalized group assessed at 54 months of age comprised 59 children.

Subject Attrition and Group Assignment

At the outset of our study, we obtained agreements ensuring that any child we placed in foster care would never have to return to an institution (during or after the study). On the other hand, some children in both the group receiving care as usual and the foster care group were adopted, and some were returned to their biological parents. Similarly, some children in the usual care group were placed in government-sponsored foster care that did not exist at the outset of the study ( Figure 1 ). Placement decisions were made by the Romanian National Authority for Child Protection in keeping with Romanian law.

The children who were lost to follow-up or excluded after random assignment in the usual care group (N=16) and foster care group (N=9) were compared on baseline characteristics to the children who remained in the study at 54 months. The groups did not differ on gender, ethnicity, birth weight, weight, developmental quotient, age at baseline, or quality of caregiving. Children who left the study were shorter at baseline than those who were retained (p=0.03, Fisher’s exact test).

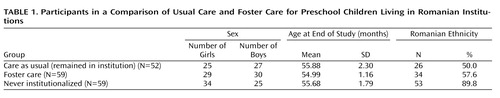

Although some children changed group assignment over time, an intent-to-treat approach was followed for the results reported herein, whereby each analysis considered the children within their originally assigned groups despite subsequent changes in status. The final study group comprised 52 children in the care as usual group, 59 children in the foster care group, and 59 children in the never-institutionalized group ( Table 1 ).

Measures

The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) is a caregiver-report instrument, involving a highly structured protocol, with required questions and probes (21 , 24) . When symptoms were reported, their frequency, duration, and dates of onset also were collected, to determine whether they met the criteria for the various DSM diagnoses. The test-retest reliability of the PAPA is comparable to that of structured psychiatric interviews used to assess older children and adults (21) .

Version 1.3 of the PAPA was translated into Romanian, back-translated into English, and assessed for meaning at each step by bilingual research staff. The lead interviewer of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project was trained in administration of the PAPA by the group who developed the measure, and he subsequently trained other Romanian interviewers.

For children living with biological parents or foster parents, the mother reported on the child’s behavior. For children living in institutions, an institutional caregiver reported on the child’s behavior. The caregiver chosen was the one considered the child’s favorite, according to staff consensus, or if the child had no favorite, was a caregiver who worked with the child regularly and knew the child well.

The DSM-IV-TR (25) symptom and diagnostic algorithms created for the English version of the PAPA were used to generate diagnoses and scale scores from the Romanian PAPA. In addition to specific diagnoses, composite disorders were also developed. “Externalizing disorders” included ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. “Internalizing disorders” included depression and anxiety disorders. “Any disorder” included the diagnoses listed in Table 2 in addition to sleep disorders, enuresis, encopresis, and reactive attachment disorder. Counts of the number of diagnostic criteria met for each of the diagnoses also were recorded.

The PAPA assesses impairment (separate from symptoms) in 30 areas including the child’s relationships with primary caregivers, other adults, siblings, and peers, as well as functioning in the home or institution, at school or day care, and outside of the home or institution.

Intervention

Because foster care was limited in Bucharest at the outset of the study, the investigators created a foster care network in conjunction with Romanian collaborators (15 , 26) . The foster care was supported by social workers in Bucharest who received regular consultation from U.S. clinicians. After advertising and subsequent screening, 56 foster families were selected to care for 68 children. Described more fully elsewhere (26) , the foster care intervention was designed to be affordable, replicable, and grounded in findings from developmental research on caregiving quality.

Procedures

After the random assignment to continued institutional care or placement in foster care, the children were reassessed at ages 30, 42, and 54 months. The mean age at placement in foster care was 22.97 months (SD=7.01). Psychiatric interviews were conducted with the primary caregivers (biological mothers, adoptive mothers, foster mothers, or institutional caregivers) when the children were 54 months of age.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated prevalence estimates for each group, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and group comparisons, using generalized estimating equations with empirical standard errors. For disorders, we used logistic regression. The reported odds ratios are those resulting from models including all significant effects simultaneously but excluding nonsignificant effects. For analysis of symptoms, overall prevalence (the percentage of subjects endorsing one or more symptoms) was modeled with logistic regression; symptom counts were modeled with generalized regression on dichotomous dummy variables representing group membership and gender. When modeled with Poisson, the data were overdispersed (deviance/df=5). Therefore, we used the negative binomial link function, which produced a deviance/df=1 (PROC GENMOD in SAS version 8.02, negative binomial distribution and logarithmic link function) (27) .

Consent

Studies involving vulnerable populations require special consideration. We and others have discussed the ethical issues involved in this study in some detail elsewhere, and we refer the interested reader to those sources (28 – 32) . Following approvals by the institutional review boards of the three principal investigators (C.H.Z., C.A.N., and N.A.F.) and by the local Commissions on Child Protection in Bucharest, the study commenced in collaboration with the Institute of Maternal and Child Health of the Romanian Ministry of Health. Consent was signed by the Commissioner for Child Protection for each institutionalized child participant living in that commissioner’s sector of Bucharest, as dictated by Romanian law. Parents of the never-institutionalized children consented to their participation. Further assent for each procedure was obtained from each caregiver who accompanied the child to the visit. In 2002, the study was approved by an ad hoc ethics committee appointed by the Ministry of Health in Romania.

Results

Psychiatric Disorders by Group

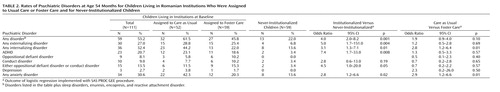

Table 2 presents the percentages of the major individual and composite DSM-IV disorders in each of the three groups. Compared to the children who had never lived in institutions, those who had ever lived in an institution (the foster care and usual care groups combined) were significantly more likely to meet criteria for any psychiatric disorder, as well as both externalizing and internalizing disorders ( Table 2 ). These results provide a rough gauge of the magnitude of morbidity in children with histories of institutional rearing.

The children who received care as usual had a higher prevalence rate of any disorder than children in the foster care group, but the difference was not significant ( Table 2 ). On the other hand, children in the usual care group were significantly more likely to meet criteria for an internalizing disorder than those in the foster care group; this difference was accounted for primarily by fewer anxiety disorders in the foster care group. There were no significant differences for the externalizing disorders overall or for specific externalizing disorders (ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, or conduct disorder). The total rates of any disorder and externalizing and internalizing composites are the most important comparisons of the two groups of children who were randomly assigned to treatment, but information about rates of specific disorders (e.g., ADHD) and smaller clusters of composite disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders) are also included in the table for completeness, although power limitations make these findings preliminary.

Comorbidity of Disorders

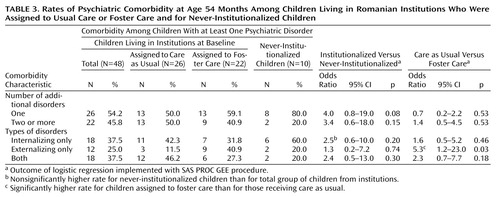

We grouped all the anxiety disorder diagnoses together into one group and the depressive disorders into another but treated the other disorders (i.e., oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and ADHD) individually to examine rates of comorbidity (two or more disorders) in children who met the criteria for at least one disorder. Table 3 shows 1) the rates of overall comorbidity for the three groups and 2) the rates of comorbidity for the internalizing and externalizing disorders. The children assigned to foster care were more likely than those receiving usual care to have “pure” externalizing disorders, whereas there was a nonsignificant difference suggesting that the usual care children were more likely to have comorbid internalizing and externalizing disorders.

Impairment

We calculated the total number of types of impairment for each child on the basis of the 30 areas assessed by the PAPA. Comparing the numbers for the children in the foster care and usual care groups revealed that the group-by-gender interaction was significant (χ 2 =6.90, df=1, p<0.009). The group difference was not significant (χ 2 =3.36, df=1, p=0.07), although girls had fewer areas of impairment than boys (χ 2 =53.42, df=1, p<0.01). Girls in the foster care group had significantly fewer types of impairment than girls in the usual care group (χ 2 =7.23, df=1, p<0.007), whereas there was no difference between boys in the two groups (χ 2 =0.51, df=1, p=0.48).

Symptom Counts

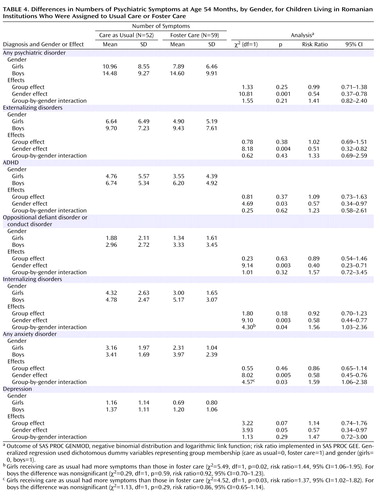

We used total counts of symptoms of various disorders to examine psychiatric morbidity beyond diagnoses. Table 4 displays the raw mean symptom counts, displayed separately for boys and for girls, as well as the differences between foster care and usual care and between boys and girls. Intervention effects were not evident for individual or composite disorders. Strikingly, girls had fewer symptoms than boys in every specific and composite disorder examined except for depression.

The group-by-gender interactions were significant for symptoms of internalizing disorders and anxiety disorders ( Table 4 ). Girls in foster care had fewer symptoms than girls in the usual care group for total symptoms (χ 2 =13.41, df=1, p<0.001), externalizing symptoms (χ 2 =7.10, df=1, p<0.008), and internalizing symptoms (χ 2 =6.41, df=1, p<0.02), whereas there was no difference between boys in the two groups for total symptoms (χ 2 =0.03, df=1, p=0.86), externalizing symptoms (χ 2 =0.04, df=1, p=0.84), or internalizing symptoms (χ 2 =0.43, df=1, p=0.52).

Gender Differences in Never-Institutionalized Children

Because of the number and magnitude of gender differences in the usual care and foster care groups, we examined differences in the symptom counts of boys and girls in the never-institutionalized group. Differences were evident for total symptoms (χ 2 =11.70, df=1, p<0.001), externalizing symptoms (χ 2 =17.92, df=1, p<0.001), ADHD symptoms (χ 2 =9.03, df=1, p<0.003), and symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder (χ 2 =9.01, df=1, p<0.003), and there was a nearly significant difference in the total number of areas of impairment (χ 2 =3.56, df=1, p=0.06). There were no statistically significant differences, however, for internalizing symptoms (χ 2 =0.46, df=1, p=0.50), anxiety symptoms (χ 2 =0.06, df=1, p=0.82), or depression symptoms (χ 2 =1.66, df=1, p=0.20).

Timing Effects

There was no relationship between age at placement in the institution, age at foster care placement, or length of institutional care and psychiatric disorders or symptoms.

Other Covariates

Because IQ differences between the usual care and foster care groups were previously reported (31) , we examined the relationship between IQ and psychiatric symptoms and disorders and found none. We also examined ethnicity and found no differences between the groups receiving care as usual and foster care, except that the total number of symptoms was lower among the Rroma (p=0.03).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the Bucharest Early Intervention Project is the first randomized trial to evaluate foster care as an alternative to institutional care for abandoned children and the first study to assess psychiatric disorders comprehensively among young children raised in institutions. A number of significant findings emerged from the current study.

Altering early experience by removing young children from institutions and placing them in families reduced the prevalence of internalizing psychiatric disorders at 54 months of age. Although the effects of the intervention on internalizing disorders were impressive, it is possible that even earlier intervention could have produced even more powerful effects. In particular, randomly assigning children at birth to institutional care or foster care might have led to additional reductions in psychopathology, although we did not detect any effects of the timing of intervention, which ranged from 6 to 30 months. The mechanism through which our foster care parenting intervention (26) reduced internalizing disorders remains to be clarified. Foster parents were explicitly encouraged to adopt a nurturing approach to parenting, and after placement in foster families, the children exhibited more secure and fewer atypical attachment classifications than they had with institutional caregivers before the intervention (33) . It is certainly plausible that more sensitive and responsive care also led to a greater reduction in internalizing disorders.

In contrast to the intervention effects with internalizing problems, there were no significant differences between the two groups (care as usual versus foster care) in ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, or conduct disorder. Of course, it is possible that the study was underpowered to detect differences or that, as already noted, earlier intervention could have produced differences between groups or that effects may become evident at subsequent ages. It is also possible that our foster parent intervention was not as intensively or as systematically focused on praise and limit setting as evidence-based treatments for externalizing behaviors in young children (34) .

Unfortunately, there are few comparable intervention studies that might illuminate the selective effect of foster placement on reducing internalizing rather than externalizing symptoms and disorders in preschool children. One study of preschool children in foster care, however, found that children with prenatal drug exposure and those who had lost multiple primary caregivers seemed to demonstrate consistently greater levels of aggression and had greater difficulties in developing trusting connections with their caregivers, even when intensive behavioral treatment was provided to foster parents (35) . These risks were quite prevalent among both institutionalized groups in our study.

In addition, the developmental psychopathology literature suggests that externalizing problems are more likely to have earlier onsets than internalizing disorders. Also, boys are more likely to be overrepresented (36 – 38) . There is considerable debate regarding the differential emergence of behavior problems in boys and girls. Among the mechanisms proposed for the earlier emergence of externalizing problems in boys than in girls are greater immaturity and hence vulnerability to high-risk environments in boys, slower maturation of abilities needed for adaptive behavior regulation in boys, differential socialization of emotion-regulation strategies in boys and girls, and differential acceptance by society of externalizing behavior in boys and girls (36) . In the uniquely challenging environment of institutional rearing, being a girl is an important protective factor with respect to virtually all types of psychiatric symptoms. This could derive from greater biological vulnerability in males, cultural practices leading to differences in how boys with any types of symptoms are responded to, or better ability among girls to make use of enhanced caregiving. The paucity of developmental research in the Romanian context does not permit choosing among these alternatives at present.

Some may question whether the different relationships between institutional caregivers and young children and foster parents and young children may have led to a systematic bias in results. While reporter bias may be possible, we believe that our results are valid for several reasons. Institutional caregivers are the adults who most resemble parents for young children in institutions, functioning in loco parentis in all day-to-day activities. All caregivers who completed PAPA interviews knew the children they reported on quite well. Although there may have been differences in institutional caregivers’ emotional investments in the children, they also (like teachers) arguably had a better grasp of the range of individual differences in behaviors and emotions exhibited by children at a given age, since they worked with particular age groups within the institutional settings. As well, there is no obvious reason why institutional caregivers or foster parents would be selectively biased (in opposite directions) about internalizing signs and symptoms and not externalizing signs or other problems. Thus, it is unlikely that caregiver reporter bias accounts for the current findings.

It is clear that the psychiatric morbidity associated with institutional rearing is considerable. The proportion of children with at least one disorder and the degree of impairment associated with these disorders both were substantially greater among children with a history of institutional rearing. The never-institutionalized children were not randomly assigned, and factors other than institutional rearing likely contributed to the rates of disorders in the usual care and foster care groups. Nevertheless, as a marker of psychopathology, institutional rearing carries considerable weight as a risk factor. It is important to note that the rates of disorders in the 54-month-old never-institutionalized children recruited from pediatric clinics in Bucharest are nearly identical to the rates of disorders of 2- to 5-year-old children recruited from pediatric clinics in North Carolina (21) , suggesting that the reported findings are meaningful beyond children living in Bucharest.

Although the intervention prevented some psychopathology, the recovery of children was incomplete, at least at 54 months of age. This is important, given that a UNICEF estimate is that there are 100,000,000 orphaned and abandoned children around the world, and thousands of these abandoned children younger than 3 years old are living in institutions throughout Western as well as Eastern Europe (39 , 40) .

Results from this study also have implications beyond institutional rearing. They suggest not only that psychiatric morbidity is associated with adverse caregiving experiences but also that ameliorating those experiences may lead to meaningful reductions in morbidity. This adds to a growing body of literature about the urgency of altering developmental trajectories in the early years because of the uniquely powerful influence that early experiences have in shaping subsequent outcomes (41) .

1. Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF: Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord 2004; 82:217–225Google Scholar

2. Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH: Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA 2001; 286:3089–3096Google Scholar

3. Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF: Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1453–1460Google Scholar

4. Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ: A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64:49–56Google Scholar

5. Zeanah CH, Smyke AT, Settles L: Orphanages as a developmental context for early childhood, in Blackwell Scientific Handbook of Early Childhood Development. Edited by McCartney K, Phillips D. Malden, Mass, Blackwell Scientific, 2006, pp 424–454Google Scholar

6. Chisholm K: A three year follow-up of attachment and indiscriminate friendliness in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Child Dev 1998; 69:1092–1106Google Scholar

7. O’Connor TG, Marvin RS, Rutter M, Olrick JT, Brittner PA, English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team: Child-parent attachment following severe early institutional deprivation. Dev Psychopathol 2003; 15:19–38Google Scholar

8. Kreppner J, O’Connor TG, Rutter M, English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team: Can inattention/overactivity be an institutional deprivation syndrome? J Abnorm Child Psychol 2001; 29:513–528Google Scholar

9. Roy P, Rutter M, Pickles A: Institutional care: associations between overactivity and lack of selectivity in social relationships. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004; 45:866–873Google Scholar

10. Hoksbergen RA, ter Laak J, van Dijkum C, Rijk S, Rijk K, Stoutjesdijk F: Posttraumatic stress disorder in adopted children from Romania. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2003; 73:255–265Google Scholar

11. Juffer F, van Ijzendoorn MH: Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2005; 293:2501–2515Google Scholar

12. Vorria P, Papaligoura Z, Sarafidou J, Koppakaki M, Dunn J, van Ijzendoorn MH, Kontopoulou A: The development of adopted children after institutional care: a follow-up study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006; 47:1246–1253Google Scholar

13. Smyke AT, Dumitrescu A, Zeanah CH: Disturbances of attachment in young children, I: the continuum of caretaking casualty. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:972–982Google Scholar

14. Smyke AT, Koga SF, Johnson DE, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Nelson CA, Zeanah CZ, BEIP Core Group: The caregiving context in institution reared and family reared infants and toddlers in Romania. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007; 48:210–218Google Scholar

15. Zeanah CH, Nelson CA, Fox NA, Smyke AT, Marshall P, Parker S, Koga S: Designing research to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behavioral development: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Dev Psychopathol 2003; 15:885–907Google Scholar

16. Fisher L, Ames EW, Chisholm K, Savoie L: Problems reported by parents of Romanian orphans adopted to British Columbia. Int J Behav Dev 1997; 20:67–82Google Scholar

17. Marcovitch S, Goldberg S, Gold A, Wash J, Wasson C, Krekewich K, Handley-Derry M: Determinants of behavioral problems in Romanian children adopted in Ontario. Int J Behav Dev 1997; 20:17–31Google Scholar

18. Roy P, Rutter M, Pickles A: Institutional care: risk from family background or pattern of rearing? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2000; 41:139–149Google Scholar

19. Sameroff AJ (ed): The Transactional Model of Development: How Children and Contexts Shape Each Other. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2009Google Scholar

20. Lavigne JV, Gibbons RD, Christoffel KK, Arend R, Rosenbaum D, Binns H, Dawson N, Sobel H, Isaacs C: Prevalence rates and correlates of psychiatric disorders among preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:204–214Google Scholar

21. Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter BK, Angold A: Test-retest reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:538–549Google Scholar

22. Tanner JM: Physical growth and development, in Textbook of Pediatrics, 2nd ed. Edited by Forfar JO, Arneil GC. London, Churchill Livingstone, 1978, pp 249–303Google Scholar

23. Department of Health and Human Services: 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development. Vital Health Stat 2000; 11(246)Google Scholar

24. Egger HL, Ascher BH, Angold A: The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment: Version 1.1. Durham, NC, Duke University Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Center for Developmental Epidemiology, 1999Google Scholar

25. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

26. Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA: A new model of foster care for young children: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am (in press)Google Scholar

27. SAS/STAT User’s Guide version 8.02. Cary, NC, SAS Institute; 2001Google Scholar

28. Zeanah CH, Koga SF, Simion B, Stanescu A, Tabacaru CL, Fox NA, Nelson CA, BEIP Core Group: Ethical considerations in international research collaboration: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Infant Ment Health J 2006; 27:559–576Google Scholar

29. Wasanaar DR: Ethical considerations in international research collaboration: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (commentary). Infant Ment Health J 2006; 27:577–580Google Scholar

30. Zeanah CH, Koga SF, Simion B, Stanescu A, Tabacaru CL, Fox NA, Nelson CA, BEIP Core Group: Ethical dimensions of the BEIP (response to commentary). Infant Ment Health J 2006; 27:581–583Google Scholar

31. Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Smyke AT, Guthrie D: Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science 2007; 318:1937–1940Google Scholar

32. Millum J, Emanuel EJ: The ethics of international research with abandoned children. Science 2007; 318:1874–1875Google Scholar

33. Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA, Guthrie D. Placement in foster care enhances attachment among young children in institutions. Child Dev (in press)Google Scholar

34. Herschell AD, Calzada EJ, Eyberg SM, McNeil CB: Parent-child interaction therapy: new directions in research. Cogn Behav Pract 2002; 9:9–15Google Scholar

35. Fisher PA, Ellis BH, Chamberlain P: Early intervention foster care: a model of preventing risk in young children who have been maltreated. Children’s Services: Social Policy, Research, and Practice 1999; 2:159–182Google Scholar

36. Crick NR, Zahn-Waxler C: The development of psychopathology in females and males: current progress and future challenges. Dev Psychopathol 2003; 15:719–742Google Scholar

37. Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K: Disorders of childhood and adolescence: gender and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2008; 4:275–303Google Scholar

38. Gadow KD, Sprafkin J, Nolan EE: DSM-IV symptoms in community and clinic preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:1383–1392Google Scholar

39. UNICEF: Children on the Brink: A Focussed Situation Analysis of Vulnerable, Excluded, and Discriminated Children in Romania. Bucharest, Vanemonde, 2006 (http://www.unicef.org/romania/sitan_engleza.pdf)Google Scholar

40. European Union Daphne Programme: Mapping the Number and Characteristics of Children Under Three in Institutions Across Europe at Risk of Harm: Daphne Project 2002-017/C. http://ec.europa.eu/justice_home/daphnetoolkit/files/projects/2002_017/03_final_report_2002_017.pdfGoogle Scholar

41. Knudsen E, Heckman J, Cameron J, Shonkoff J: Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:10155–10162Google Scholar