Meta-Analysis of the Symptom Structure of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Abstract

Objective: OCD is a clinically heterogeneous condition. This heterogeneity has the potential to reduce power in genetic, neuroimaging, and clinical trials. Despite a mounting number of studies, there remains debate regarding the exact factor structure of OCD symptoms. The authors conducted a meta-analysis to determine the factor structure of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Symptom Checklist. Method: Studies were included if they involved subjects with OCD and included an exploratory factor analysis of the 13 Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Symptom Checklist categories or the items therein. A varimax-rotation was conducted in SAS 9.1 using the PROC FACTOR CORR to extract factors from sample-size weighted co-occurrence matrices. Stratified meta-analysis was conducted to determine the factor structure of OCD in studies involving children and adults separately. Results: Twenty-one studies involving 5,124 participants were included. The four factors generated were 1) symmetry: symmetry obsessions and repeating, ordering, and counting compulsions; 2) forbidden thoughts: aggression, sexual, religious, and somatic obsessions and checking compulsions, 3) cleaning: cleaning and contamination, and 4) hoarding: hoarding obsessions and compulsions. Factor analysis of studies including adults yielded an identical factor structure compared to the overall meta-analysis. Factor analysis of child-only studies differed in that checking loaded highest on the symmetry factor and somatic obsessions, on the cleaning factor. Conclusions: A four-factor structure explained a large proportion of the heterogeneity in the clinical symptoms of OCD. Further item-level factor analyses are needed to determine the appropriate placement of miscellaneous somatic and checking OCD symptoms.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by repetitive, intrusive thoughts and images and/or by repetitive, ritualistic physical or mental acts performed to reduce the attendant anxiety. OCD is common, affecting 1%–3% of people in both adult and pediatric samples (1 – 3) . OCD is a clinically heterogeneous condition such that two patients with clear OCD can display completely distinct symptom patterns. Despite this obvious phenotypic heterogeneity, DSM-IV and ICD-10 have regarded OCD as a unitary nosological entity. This heterogeneity has the potential to reduce power in genetic, neuroimaging and natural history studies as well as clinical trials (4) .

With the ongoing deliberations concerning DSM-V, a vast majority of OCD experts surveyed worldwide agreed that “OCD was heterogeneous, that symptoms are experienced within multiple potentially overlapping symptom dimensions and that it would be important to document them as specifiers in DSM-V ” (5) . Over 20 factor analytic studies conducted on large cohorts of OCD patients have identified possible symptom dimensions in OCD. Furthermore, these dimensions have been associated with distinct patterns of comorbid psychiatric conditions (6) , different patterns of heritability (7) , specific genetic polymorphisms (8) , and distinct symptom-associated patterns of neural activity as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (9) . Perhaps most important, specific symptom dimensions have been associated with differential response to pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments (10 , 11) .

Despite this strong scientific evidence and the potential benefits of dimensional approaches to OCD, several challenges to their implementation remain. Factor analytic studies of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) have reported between three and five factors. Although the pairings of some symptom categories in these studies have remained consistent (i.e., hoarding obsessions with hoarding compulsions, contamination obsessions with cleaning compulsions, symmetry obsessions with ordering compulsions), the appropriate treatment of other symptom categories remains in doubt (i.e., somatic obsessions, counting, checking and repeating compulsions, and the factor structure documenting the relationship between aggressive, sexual, and religious obsessions). Given this controversy in the field about the correct number of factors and the appropriate factor structure for OCD, most investigators have chosen to conduct their own exploratory factor analyses and report scientific results as compared to their uniquely generated factors. This practice has made it very difficult to replicate or interpret clinical or research studies incorporating a dimensional structure of OCD. Alternatively, some authors have used confirmatory factor analysis to test the fit of their data against previously generated factor structures. However, the possible solutions of confirmatory factor analytic studies are limited to the previously generated factor solutions tested in the particular study. To our knowledge, only one confirmatory factor analysis has been published that compares different proposed factor structures of OCD, and this analysis only tested between the earliest two-to-four factor analytic solutions for OCD (12) .

Although the results of factor analytic studies can appear quite different when compared subjectively, it remains quite possible that the relationship between symptom categories in many factor analytic studies are similar but this similarity is masked through differences in factor number and factor rotation. To clarify this issue, we conducted a meta-analysis of factor analytic studies of the 13 major symptom categories of the Y-BOCS symptom checklist with the goal of determining a robust model of the dimensional structure of OCD for both adults and children synthesizing data from all published exploratory factor analyses.

Method

Search Strategy for Identification of Studies

Two reviewers (M.H.B. and A.L.-W.) searched the electronic databases of PubMed and PsycINFO for relevant studies using the search terms (obsessive-compulsive disorder or OCD OR Y-BOCS) and (factor analytic studies or factor or dimension). The references of appropriate articles and review articles in this area were searched for citations of further relevant published and unpublished research.

Selection of Studies

The titles and abstracts of studies obtained by this search strategy were scrutinized by two reviewers (M.H.B. and A.L.-W.) to determine if they were potentially eligible for inclusion in this review.

Eligibility for the study was based upon scrutiny of the full articles for the following inclusion criteria: 1) the population included in the study had an axis I OCD diagnosis, 2) they were exploratory factor analytic studies of the Y-BOCS or the CY-BOCS and 3) Factor analysis was based on and included at least the 13 main symptom categories of the Y-BOCS. Therefore, for a study to be eligible, it must have included at least the 13 main symptom categories in the Y-BOCS Checklist (seven categories of obsessions: aggression, contamination, sexual, hoarding, religious, symmetry, somatic and six categories of compulsions: cleaning, checking, repeating, counting, ordering, hoarding) or the individual items therein. Studies were included in this meta-analysis if they also included additional symptom categories in their factor analysis such as miscellaneous obsessions and compulsions from the Y-BOCS CL or magical thoughts, superstitious behaviors, rituals involving others from the CY-BOCS CL. Item-by-item factor analyses of the Y-BOCS or CY-BOCS CL were also eligible for this systematic review. Confirmatory factor analyses were not eligible for this review, as they require specification of the models to be tested in advance and so do not compute relationships between the factors uniquely for their data set. Including confirmatory factor analysis in this meta-analysis would bias the results toward the solutions of earlier published studies.

Meta-Analytic Procedure Used

The meta-analytic procedure adopted for this systematic review was based upon the methods used by Shafer in previous meta-analyses of psychiatric rating scales (13 , 14) . In this method a matrix of sample-size weighted similarity coefficients between each of the 13 Y-BOCS symptom categories was computed in the meta-analysis. The matrix of sample-size-weighted similarity coefficients was computed in the following manner: for each individual study a raw co-occurrence matrix for each pair of Y-BOCS symptom category items was computed. In the raw co-occurrence matrix for each study, if a pair of Y-BOCS symptom category items both had their highest factor loadings on the same factor and both their factor loadings were above 0.4, they were assigned a value of 1. Otherwise, they were given a score of 0. For item-level factor analyses, the item-level factor solutions for the individual studies were translated back into the original 13 Y-BOCS headings. A Y-BOCS symptom category was determined to load on a particular factor in an item level if more than half of its component items loaded on a particular factor with a factor loading of greater than 0.4. After this adjustment, correlation matrices for item-level factor analytic studies were computed in a similar manner to category level data. When both category-level and item-level factor analytic data were presented for a particular study, category-level data were used preferentially, because category-level data were the primary unit of measure for this review. When the highest factor loadings for specific Y-BOCS items was not available (a rare occurrence), study investigators were contacted for further information, which was made available in all cases.

The raw co-occurrence matrix for each study was multiplied by its sample size, creating the sample-size weighted co-occurrence matrix. The sample-size weighted co-occurrence matrices for all included studies in the meta-analysis were added together and then divided by the pooled sample size, producing a composite sample-size weighted co-occurrence matrix. Composite sample-sized weighted co-occurrence matrices were computed first for all the factor analytic studies. We then stratified results by age (adults versus children) and the primary language of the participants (English versus non-English) of the individual studies. We further stratified results to examine different methods of data analysis such as the use of current versus lifetime symptoms, category-versus item-level data, scoring system (present/absent, number of symptoms endorsed and symptom severity ratings within categories, were symptoms in a particular dimension absent, present, or predominant), and type of rotation (orthogonal [varimax] or oblique [promax or oblimin]). For the analysis involving stratification by age of sample, a study was considered an adult study if 1) all subjects were over 18 years old or 2) the mean age of the sample minus 1 SD was greater than 18 years. A sample was considered a child sample if 1) all subjects were less than 18 years old or 2) the mean age plus 1 SD was less than 18 years. For calculation of the composite sample-size weighted co-occurrence matrices, data were extracted from individual studies by two separate authors (M.H.B. and A.L.-W.) independently and meta-analyzed with a special spreadsheet designed specifically for this meta-analysis. The percent agreement of category scores in the unweighted co-occurrence matrices for the individual studies was 99.3% between the two reviewers (100% for category and 95.2% agreement for item-level studies). Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved through discussion after completion of the data extraction step of this study.

In order to determine the factor structure for the each of the three composite sample-size weighted co-occurrence matrices above (adults, children, and total samples), a principal component analysis was conducted in SAS 9.1 using the PROC FACTOR CORR command. The sample-size weighted co-occurrence matrices served as the correlation matrix for each analysis. A varimax rotation was used to assist in factor identification. The criterion used to select the number of factors was an eigenvalue greater than 1, also known as Kaiser’s criterion. A promax rotation was also used in order to test the hypothesis that allowing factor to be intercorrelated would not affect the results. When necessary for the sake of comparison, post hoc, factor analyses were also conducted to force two, three, four, or five factor solutions for each of the stratified data sets.

Results

Included Studies

A total of 21 factor analytic studies of the Y-BOCS CL involving 5,124 participants were included in this meta-analysis (6 , 10 , 15 – 33) . Table 1 displays the demographic information and results of these individual studies.

Excluded Studies

We excluded several well-conducted factor analyses of the Y-BOCS CL because they did not meet our a priori inclusion criteria. One study was excluded because it involved mostly psychiatric patients without OCD (34) . Another study was excluded because it involved a population of patients with a primary diagnosis of Tourette’s syndrome (7) . Two published factor analyses were excluded because their samples largely overlapped with other studies included in our meta-analysis (8 , 35) , and another one was excluded as it was a confirmatory factor analysis of the Y-BOCS CL (12) .

Factor Analysis Results for Total Sample

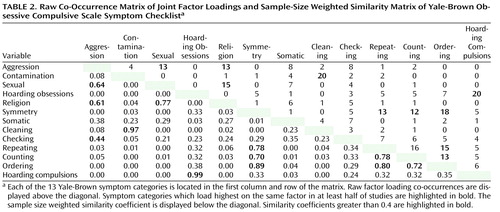

The unweighted symptom co-occurrence matrix of studies and sample-size weighted correlation matrix of Y-BOCS symptom categories is displayed in Table 2 . The greatest agreement between studies was on the association between hoarding obsessions and hoarding compulsions and between contamination and cleaning. Twenty of 21 studies associated hoarding obsessions with hoarding compulsions and cleaning compulsions with contamination obsessions. The greatest disagreement was in the placement of checking compulsions, which was associated with every other symptom category in at least one factor analysis.

Using all available data, the factor analysis generated four factors that explained 79.0% of the variance. Table 3 displays the results of the varimax-rotated factor analysis. Symmetry obsessions and repeating, ordering, and counting compulsions loaded highly on factor 1 (26.7%). Aggression, sexual, religious and somatic obsessions and checking compulsions loaded highly on factor 2 (21.0%). Cleaning and contamination loaded highly on factor 3 (15.9%). Hoarding obsessions and compulsions loaded highly on factor 4 (15.4%). Promax-rotated factor analysis yielded an identical factor structure to varimax rotation. When a five-factor solution was forced, somatic obsessions and checking compulsions separated out into a fifth factor. When a three-factor solution was forced, the hoarding (factor 4) and symmetry (factor 1) combined to form a single factor.

Factor Analysis Results for Studies Involving Adults and Children

Four studies involving 679 participants were conducted on children (26 – 29) , and 17 studies involving 4,445 participants were of adults (6 , 10 , 16 – 25 , 30 – 33) . The factor structure of the studies involving adults was identical to those involving the total sample. This four-factor solution explained 79.7% of the variance in the studies involving adults. Table 3 depicts the results for the varimax-rotated factor analysis of the studies involving adults. Promax rotation did not affect the generated factor structure.

Factor analysis of studies involving children generated four factors that explained 81.7% of the total variance. Symmetry obsessions and checking, repeating, ordering, and counting compulsions loaded highly on factor 1 (28.7%). Cleaning, contamination, and somatic obsessions loaded highly on factor 2 (19.9%). Hoarding obsessions and compulsions loaded highly on factor 3 (16.7%). Aggressive, sexual, and religious obsessions loaded highly on factor 4 (16.4%). Table 3 depicts the results for the varimax-rotated factor analysis of the studies involving children.

Factor Analysis Results for Studies Involving English-Speaking and Non-English-Speaking Subjects

Twelve studies involving 2,775 subjects involved primarily English-speaking subjects (6 , 10 , 16 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 25 , 27 – 29 , 31) . Factor analysis generated four factors that explained 81.5% of the variance. The result of factor analysis in studies with English-speaking samples was identical to that of the total sample. Symmetry obsessions and repeating, ordering, and counting compulsions loaded highly on factor 1 (26.7%). Aggression, sexual, religious, and somatic obsessions and checking compulsions loaded highly on factor 2 (23.8%). Hoarding obsessions and compulsions loaded highly on factor 3 (15.5%). Cleaning compulsions and contamination obsessions loaded highly on factor 4 (15.4%).

Eight studies involving 1,917 subjects involved subjects from non-English-speaking countries (15 , 17 , 19 , 22 , 24 , 26 , 30 , 33) . Factor analysis generated a four-factor solution that explained 77.8% of the variance. Symmetry obsessions and repeating, ordering, counting, and checking compulsions as well as hoarding obsessions and compulsions loaded highest on factor 1 (36.1%). Cleaning compulsions and contamination obsessions loaded highly on factor 2 (15.9%). Aggression, sexual, and religious obsessions loaded highly on factor 3 (15.4%). Aggression, somatic, and checking symptoms loaded highly on factor 4 (10.3%). One study was excluded from the stratified meta-analysis of English versus non-English speakers because it contained data from both groups (32) .

Factor Analysis Results for Studies Using Category- Versus Item-Level Symptoms

Eighteen studies involving 4,153 subjects were included in studies using category-level data (6 , 10 , 16 – 31) . The results of factor analysis yielded a four-factor solution that explained 80.0% of the variance and was identical to that of the total sample. Symmetry obsessions and repeating, ordering, and counting compulsions loaded highly on factor 1 (27.9%). Aggression, sexual, religious, and somatic obsessions and checking compulsions loaded highly on factor 2 (21.6%). Cleaning and contamination loaded highly on factor 3 (16.1%). Hoarding obsessions and compulsions loaded highly on factor 4 (15.6%).

Five studies involving 1,746 subjects were included in studies that analyzed item-level data (17 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36) . Factor analysis yielded a five-factor solution that explained 73.8% of the variance. Symmetry obsessions and repeating, ordering, and counting compulsions as well as hoarding obsessions and compulsion loaded highly on factor 1 (31.3%). Aggression, sexual, and religious obsessions loaded highly on factor 2 (12.9%). Cleaning compulsions and contamination obsessions loaded highly on factor 3 (12.2%). Aggression obsessions and checking compulsions loaded highly on factor 4 (9.7%). Somatic obsessions loaded highly on factor 5 (7.7%). Two studies that contained both category- and item-level data contributed to both groups in the stratified meta-analysis (17 , 31) .

Factor Analysis Results for Studies Using Current Versus Lifetime Symptoms

Twelve studies involving 2,830 subjects used current OCD symptoms only in factor analysis (10 , 11 , 16 , 17 , 19 , 20 , 26 , 27 , 30 , 31 , 35 , 36) . Factor analysis for studies using current OCD symptoms yielded a four-factor solution that explained 81.2% of the variance. Symmetry obsessions and repeating, ordering, and counting loaded highest on factor 1 (31.3%). Aggression, sexual, and religious obsessions and checking compulsions loaded highly on factor 2 (18.2%). Cleaning compulsions and contamination obsessions loaded highly on factor 3 (16.7%). Hoarding obsessions and compulsions loaded highly on factor 4 (15.6%)

Nine studies involving 2,294 participants used lifetime OCD symptoms for factor analysis (6 , 18 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 33) . Factor analysis for these studies yielded a four-factor solution identical in structure to the total sample that explained 85.0% of the variance. Aggression, sexual, religious, and somatic obsessions and checking compulsions loaded highly on factor 1 (27.2%). Symmetry obsessions and repeating, ordering, and counting compulsions loaded highly on factor 2 (26.5%). Cleaning and contamination loaded highly on factor 3 (15.7%). Hoarding obsessions and compulsions loaded highly on factor 4 (15.5%).

Factor Analysis Results for Studies Based on Symptom Scoring

There were nine studies involving 2,205 subjects that classified OCD symptoms based on the number of symptoms endorsed by the patient within each category (18 , 20 , 22 , 24 , 29 . Factor analysis for these studies yielded a four-factor solution similar to the results from the total sample, explaining 79.3% of the variance. Aggression, sexual, religious, and somatic obsessions and checking compulsions loaded highly on factor 1 (25.4%). Symmetry obsessions and repeating, ordering, and counting compulsions loaded highly on factor 2 (23.3%). Hoarding obsessions and compulsions loaded highly on factor 3 (15.5%). Cleaning and contamination loaded highly on factor 4 (15.2%).

Seven studies involving 1,565 subjects classified OCD symptoms in each category based on the presence or absence of symptoms in each category (6 , 17 , 21 , 23 , 30 , 31 , 33) . Factor analysis yielded a four-factor solution that explained 82.8% of the variance. This four-factor solution was identical to that of the results for the total sample except that checking symptoms loaded highest on the symmetry factor and somatic symptoms loaded highest on the cleaning factor.

Five studies involving 1,354 subjects used category-wide symptom severity ratings to classify OCD symptoms (10 , 16 , 19 , 35 , 36) . This method typically involves classifying symptoms in each category as either absent=0, present=1, or prominent or most prominent=2. Factor analysis of these studies yielded a three-factor solution that explained 73.3% of the variance. Symmetry obsessions and repeating, ordering, and counting compulsions as well as hoarding obsessions and compulsions loaded highest on factor 1 (40.3%). Cleaning and checking compulsions and contamination obsessions loaded highly on factor 2 (17.4%). Aggression, sexual, and religious obsessions loaded highly on factor 3 (15.7%). When a four-factor solution was forced, aggression, somatic, and checking symptoms separated out into the fourth factor.

Factor Analysis Results for Studies Based on Rotation Method

Eighteen studies involving 4,338 subjects used an orthogonal (varimax) rotation to separate factors in data analysis (6 , 10 , 15 – 24 , 26 , 29 – 33) . Factor analysis of these studies yielded a four-factor solution that was identical to that of the total sample except that somatic symptoms loaded highest on both the forbidden thoughts and cleaning factors. This four-factor solution explained 79.3% of the variance.

Three studies involving 786 subjects used an oblique rotation (promax or oblimin) to separate factors in data analysis (25 , 27 , 28) . Oblique methods are better at extracting correlated, overlapping factors than standard orthogonal rotations. Factor analysis of these studies yielded a four-factor solution identical to that generated for the total sample that explained 85.8% of the variance.

Discussion

The results of this meta-analysis demonstrated a fairly robust four-factor symptom structure for obsessive-compulsive symptoms across the lifespan. The four OCD factors were 1) symmetry factor, which contained symmetry obsessions and ordering, repeating, and counting compulsions, 2) forbidden thoughts factor, which contained aggression, sexual, and religious obsessions, 3) cleaning factor, which contained contamination obsessions and cleaning compulsions, and 4) hoarding factor, which contained hoarding obsessions and compulsions. These findings reinforce the recommendations of the international group of OCD experts that DSM-V should include specification of these four symptom dimensions (5) .

Figure 1 depicts this four-factor structure and compares the relationship among symptom categories in the factor analysis of studies involving adults and children as well as other subgroup analyses. The only differences between the factor structures involving adults and children were 1) checking compulsions loaded highest on the forbidden thoughts factor in adults and on the symmetry factor in children and 2) somatic obsessions loaded highest on the forbidden thoughts factor in adults and on the cleaning factor in children. When checking symptoms were examined in the total sample, they loaded highest on the forbidden thoughts factor. The shifting of checking symptoms from one factor to another is likely attributable to the inherent ambiguity of checking symptoms and their heterogeneous association of individual items within this category with other OCD symptom categories in the Y-BOCS CL. Also, because the Y-BOCS has very few checking items, which are vague in nature, Y-BOCS checking items are associated with almost all factors. For instance, “checking that harm did not come to others” and “checking tied to somatic obsessions” are both individual items with the checking category of the Y-BOCS CL. In the current analysis, checking was therefore heterogeneous and associated with multiple symptom factors, normally with the most commonly held symptom factor within each age group (i.e., symmetry in children and forbidden thoughts in adults). This ambiguity in the checking category of the Y-BOCS CL has been addressed in dimensional OCD scales such as the Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS), which associates specific checking and avoidance OCD symptoms within each obsessive-compulsive symptom dimension/factor (37) . Potentially item-level factor analyses of the Y-BOCS might help resolve the inherent ambiguity of the checking symptom category in the Y-BOCS CL.

a Symptom categories shaded in white are associated with the same factor across the lifespan. Symptom categories shaded in gray are associated with different factors in adults and children. Solid lines indicate that a symptom category is associated with a particular factor in adults. Dashed lines indicate that the symptom category is associated with a particular factor in children only. The hoarding and symmetry factors that are surrounded by a dashed box were collapsed into the same factor in some subgroup analyses, including when studies included non-English-speaking subjects or when ratings of symptom severity were used. The forbidden thoughts factor split into two separate factors in subgroup analyses involving non-English-speaking subjects and when only studies using item-level data were considered.

The switch of factor association of the somatic category between children and adults may be related to changes in the developmental view of germs and illness across the lifespan. As children mature their concept of illness changes from being associated primarily with primitive feeling states to being able to associate illness with specific disease states, restriction of activity, and changes in their social role (38) . This developmental transition in the view of disease and illness may explain the shift in association of this symptom category from the cleaning factor to the forbidden thoughts factor. Another possibility is that the prevalence of individual OCD symptom items within each category may change with chronological age and that this may explain the differing associations. Future longitudinal studies examining the obsessive-compulsive symptoms associated with somatic symptoms are warranted.

Echoing the results of the very first factor analytic study by Baer (16) , a number of the stratified subgroup analyses yielded a result in which the hoarding factor was combined with the symmetry factor. In our view, this speaks to the likely hierarchical cladistic metastructure of the obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. In this cladistic structure, it appears that the hoarding and symmetry factors are closely related to one another. Limited support for this perspective comes from when we “forced” a three-factor solution in the overall sample and these two dimensions collapsed together. We suspect that hoarding factor failed to separate out in several subanalyses in which the total number of hoarders were inadequate for them to pull out as a separate group. Thus, for these subanalyses, hoarding clustered together with its closest related OCD symptom factor: symmetry. We hypothesize that the entire set of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, including miscellaneous symptoms, will be shown to have a set “relationship” with one another. For example, we also predict that when a sufficiently large item-level factor analytic studies are conducted or a sufficiently large number of item-level factor analytic studies are conducted for meta-analysis, the forbidden thoughts factor may still divide into two separate, closely related factors. One would involve intrusive images of harm, sexual, and religious obsessions and the other would involve fear of harm coming to self or others and a specific subset of checking compulsions. This solution reflects the item-level factor analytic solution presented in this meta-analysis and multiple studies in which this solution was empirically found (10 , 29 – 31 , 33) . Further item-level studies will help clarify the exact relationship between aggression items on the Y-BOCS CL and sexual, religious, somatic, and checking OCD symptoms. The subtle ambiguities presented in the factor structure in this meta-analysis and in the plethora of factor analytic studies of OCD should not be used as negative evidence to dispute the potential utility of dimensional descriptors in OCD as these ambiguities likely represent different thresholds for cut-points in the hierarchical cladistic metastructure of obsessive-compulsive symptom dimension. Strong evidence suggests that hoarding obsessive-compulsive symptoms are quite distinct from other obsessive-compulsive symptoms in terms of patterns of heredity and comorbidity, neuroimaging, and treatment response (39 , 40) . Furthermore, although it is quite common for severe hoarders to have symmetry dimension-related obsessions, the reverse is seldom true—a significant minority of OCD patients have hoarding-related symptoms (41) . These findings suggest that hoarding may be both a separate syndrome from OCD and, more rarely, a symptom dimension of OCD (41) . The empirical validity and clinical utility of separating aggression obsessive-compulsive symptoms from sexual and religious obsessive-compulsive symptoms into separate obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions is much less clear. Therefore, we suggest a four-factor solution to describe OCD and suggest that future research studies should (1) explore the relationship of symptoms in the forbidden thoughts factor at an item level and 2) explore differences in treatment response among individuals within these symptom categories.

There are several limitations to this study, including the rather crude meta-analytic technique used to combine studies. Our meta-analytic technique used information only about whether or not Y-BOCS symptom categories loaded most strongly on the same factor and did not include the strength of these loadings within factors. This statistical technique was necessitated by the lack of published unrotated factor matrices in the literature. If unrotated factor matrices were published or available as supplementary material to manuscripts, more precise meta-analytic techniques could be employed. However, it may overestimate the strength of factor loading between categories and the percentage of symptom profiles explained overall by the four-factor structure we describe. Another limitation was the use of category-level rather than item-level data from the Y-BOCS CL. There is undoubtedly heterogeneity of factor associations within some symptom categories, especially the checking and miscellaneous categories. Further studies employing item-level factor analysis and addressing the specific associations of miscellaneous symptoms with the existing Y-BOCS factor structure are needed to address subtleties of the symptom dimensions of OCD beyond the scope of this meta-analysis.

Despite these limitations, the current meta-analysis demonstrated a four-factor dimensional solution of OCD that was fairly stable across the lifespan and fairly robust to differences in factor analytic techniques of individual meta-analyses. A similar stable four-factor structure has been demonstrated in a confirmatory factor analysis of children, adolescents, and adults with OCD (42) . OCD symptom dimensions have proven useful in decreasing phenotypic heterogeneity in genetic, neuroimaging, treatment, and phenomenological studies of OCD (4 , 43) . An important initial step in unlocking the potential power of this dimensional approach for the field is settling upon a common symptom structure. This meta-analysis, along with a recent confirmatory factor analytic study (12) , points to these same four symptom factors as the underlying factor structure of OCD. Therefore, we believe that the DSM-V diagnostic formulation of OCD should include specification of these four symptom dimensions. These DSM-V specifiers should include 1) a symmetry dimension, which would include individuals with symmetry obsessions and ordering, repeating, and counting compulsions; 2) a forbidden thoughts dimension, which would include individuals with aggression, sexual, and religious obsessions; 3) a cleaning dimension, which would include individuals with contamination obsessions; and (4) a hoarding dimension, which would include individuals with hoarding obsessions and compulsions.

1. Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam MA: The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1094–1099Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:593–602Google Scholar

3. Valleni-Basile LA, Garrison CZ, Jackson KL, Waller JL, McKeown RE, Addy CL, Cuffe SP: Frequency of obsessive-compulsive disorder in a community sample of young adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:782–791Google Scholar

4. Mataix-Cols D, Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF: A multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:228–238Google Scholar

5. Mataix-Cols D, Pertusa A, Leckman JF: Issues for DSM-V: how should obsessive-compulsive and related disorders be classified? Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1313–1314Google Scholar

6. Hasler G, LaSalle-Ricci VH, Ronquillo JG, Crawley SA, Cochran LW, Kazuba D, Greenberg BD, Murphy DL: Obsessive-compulsive disorder symptom dimensions show specific relationships to psychiatric comorbidity. Psychiatry Res 2005; 135:121–132Google Scholar

7. Leckman JF, Pauls DL, Zhang H, Rosario-Campos MC, Katsovich L, Kidd KK, Pakstis AJ, Alsobrook JP, Robertson MM, McMahon WM, Walkup JT, van de Wetering BJ, King RA, Cohen DJ: Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions in affected sibling pairs diagnosed with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2003; 116:60–68Google Scholar

8. Hasler G, Kazuba D, Murphy DL: Factor analysis of obsessive-compulsive disorder YBOCS-SC symptoms and association with 5-HTTLPR sert polymorphism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2006; 141:403–408Google Scholar

9. Mataix-Cols D, Wooderson S, Lawrence N, Brammer MJ, Speckens A, Phillips ML: Distinct neural correlates of washing, checking, and hoarding symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:564–576Google Scholar

10. Mataix-Cols D, Rauch SL, Manzo PA, Jenike MA, Baer L: Use of factor-analyzed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1409–1416Google Scholar

11. Mataix-Cols D, Marks IM, Greist JH, Kobak KA, Baer L: Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions as predictors of compliance with and response to behaviour therapy: results from a controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2002; 71:255–262Google Scholar

12. Summerfeldt LJ, Richter MA, Antony MM, Swinson RP: Symptom structure in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a confirmatory factor-analytic study. Behav Res Ther 1999; 37:297–311Google Scholar

13. Shafer A: Meta-analysis of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale factor structure. Psychol Assess 2005; 17:324–335Google Scholar

14. Shafer AB: Meta-analysis of the factor structures of four depression questionnaires: Beck, CES-D, Hamilton, and Zung. J Clin Psychol 2006; 62:123–146Google Scholar

15. Denys D, de Geus F, van Megen HJ, Westenberg HG: Use of factor analysis to detect potential phenotypes in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res 2004; 128:273–280Google Scholar

16. Baer L: Factor analysis of symptom subtypes of obsessive compulsive disorder and their relation to personality and tic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(suppl):18–23Google Scholar

17. Hantouche EG, Lancrenon S: [Modern typology of symptoms and obsessive-compulsive syndromes: results of a large French study of 615 patients]. Encephale 1996; 22; Spec No 1:9–21Google Scholar

18. Leckman JF, Grice DE, Boardman J, Zhang H, Vitale A, Bondi C, Alsobrook J, Peterson BS, Cohen DJ, Rasmussen SA, Goodman WK, McDougle CJ, Pauls DL: Symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:911–917Google Scholar

19. Kim SJ, Lee HS, Kim CH: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, factor-analyzed symptom dimensions and serotonin transporter polymorphism. Neuropsychobiology 2005; 52:176–182Google Scholar

20. Pinto A, Eisen JL, Mancebo MC, Greenberg BD, Stout RL, Rasmussen SA: Taboo thoughts and doubt/checking: a refinement of the factor structure for obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms. Psychiatry Res 2007; 151:255–258Google Scholar

21. Cullen B, Brown CH, Riddle MA, Grados M, Bienvenu OJ, Hoehn-Saric R, Shugart YY, Liang KY, Samuels J, Nestadt G: Factor analysis of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive scale in a family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety 2007; 24:130–138Google Scholar

22. Matsunaga H, Maebayashi K, Hayashida K, Okino K, Matsui T, Iketani T, Kiriike N, Stein DJ: Symptom structure in Japanese patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:251–253Google Scholar

23. Mataix-Cols D, Rauch SL, Baer L, Eisen JL, Shera DM, Goodman WK, Rasmussen SA, Jenike MA: Symptom stability in adult obsessive-compulsive disorder: data from a naturalistic two-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:263–268Google Scholar

24. Cavallini MC, Di Bella D, Siliprandi F, Malchiodi F, Bellodi L: Exploratory factor analysis of obsessive-compulsive patients and association with 5-HTTLPR polymorphism. Am J Med Genet 2002; 114:347–353Google Scholar

25. Hasler G, Pinto A, Greenberg BD, Samuels J, Fyer AJ, Pauls D, Knowles JA, McCracken JT, Piacentini J, Riddle MA, Rauch SL, Rasmussen SA, Willour VL, Grados MA, Cullen B, Bienvenu OJ, Shugart YY, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Wang Y, Ronquillo J, Nestadt G, Murphy DL: Familiality of factor analysis-derived YBOCS dimensions in OCD-affected sibling pairs from the OCD collaborative genetics study. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61:617–625Google Scholar

26. Delorme R, Bille A, Betancur C, Mathieu F, Chabane N, Mouren-Simeoni MC, Leboyer M: Exploratory analysis of obsessive compulsive symptom dimensions in children and adolescents: a prospective follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry 2006; 6:1Google Scholar

27. McKay D, Piacentini J, Greisberg S, Graae F, Jaffer M, Miller J: The structure of childhood obsessions and compulsions: dimensions in an outpatient sample. Behav Res Ther 2006; 44:137–146Google Scholar

28. Stewart SE, Rosario MC, Brown TA, Carter AS, Leckman JF, Sukhodolsky D, Katsovitch L, King R, Geller D, Pauls DL: Principal components analysis of obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms in children and adolescents. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61:285–291Google Scholar

29. Mataix-Cols D, Nakatani E, Micali N, Heyman I: The structure of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in pediatric OCD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008; 47:773–778Google Scholar

30. Tek C, Ulug B: Religiosity and religious obsessions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res 2001; 104:99–108Google Scholar

31. Feinstein SB, Fallon BA, Petkova E, Liebowitz MR: Item-by-item factor analysis of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive scale symptom checklist. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003; 15:187–193Google Scholar

32. Stein DJ, Andersen EW, Overo KF: Response of symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder to treatment with citalopram or placebo. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2007; 29:303–307Google Scholar

33. Girishchandra BG, Khanna S: Phenomenology of obsessive compulsive disorder: a factor analytic approach. Indian J Psychiatry 2001; 43:306–316Google Scholar

34. Wu KD, Watson D, Clark LA: A self-report version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale symptom checklist: psychometric properties of factor-based scales in three samples. J Anxiety Disord 2007; 21:644–661Google Scholar

35. Denys D, de Geus F, van Megen HJ, Westenberg HG: Symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder: factor analysis on a clinician-rated scale and a self-report measure. Psychopathology 2004; 37:181–189Google Scholar

36. Stein DJ, Andersen EW, Overo KF: Response of symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder to treatment with citalopram or placebo. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2007; 29:303–307Google Scholar

37. Rosario-Campos MC, Miguel EC, Quatrano S, Chacon P, Ferrao Y, Findley D, Katsovich L, Scahill L, King RA, Woody SR, Tolin D, Hollander E, Kano Y, Leckman JF: The dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive scale (DY-BOCS): an instrument for assessing obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Mol Psychiatry 2006; 11:495–504Google Scholar

38. Campbell JD: Illness is a point of view: the development of children’s concepts of illness. Child Development 1975; 46:92–100Google Scholar

39. Saxena S: Is compulsive hoarding a genetically and neurobiologically discrete syndrome? implications for diagnostic classification. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:380–384Google Scholar

40. Zhang H, Leckman JF, Pauls DL, Tsai CP, Kidd KK, Campos MR: Genomewide scan of hoarding in sib pairs in which both sibs have Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 70:896–904Google Scholar

41. Pertusa A, Fullana MA, Singh S, Alonso P, Menchón JM, Mataix-Cols D: Compulsive hoarding: OCD symptom, distinct clinical syndrome, or both? Am J Psychiatry 2008 (ePub ahead of print)Google Scholar

42. Stewart SE, Rosario MC, Baer L, Carter AS, Brown TA, Scharf JM, Illmann C, Leck JF, Sukhodolsky D, Katsovich L, Rasmussen S, Goodman W, Delorme R, Leboyer M, Chabane N, Jenike MA, Geller DA, Paul DL: Four-factor structure of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in children, adolescents and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolescent Psychiatry 2008; 47:763–772Google Scholar

43. Miguel EC, Leckman JF, Rauch S, do Rosario-Campos MC, Hounie AG, Mercadante MT, Chacon P, Pauls DL: Obsessive-compulsive disorder phenotypes: implications for genetic studies. Mol Psychiatry 2005; 10:258–275Google Scholar