Maintenance Treatment for Patients With Bipolar I Disorder: Results From a North American Study of Quetiapine in Combination With Lithium or Divalproex (Trial 127)

Abstract

Objective: The authors evaluated the efficacy and safety of quetiapine plus lithium or divalproex in the prevention of recurrent mood events in patients with stabilized bipolar I disorder. Method: A total of 1,953 patients received open-label quetiapine (400–800 mg/day in flexible, divided doses) with either lithium or divalproex (target serum concentrations 0.5–1.2 meq/liter and 50–125 μg/ml, respectively) for up to 36 weeks. After at least 12 weeks of clinical stability, 628 patients were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with quetiapine or placebo, in combination with lithium or divalproex, for up to 104 weeks. The primary efficacy measure was time to recurrence of any mood event (mania, depression, or a mixed episode). Results: Fewer patients in the quetiapine group experienced a mood event compared with the placebo group (20.3% versus 52.1%). The hazard ratio for time to recurrence of a mood event was 0.32. Hazard ratios were similar for mania and depression events (0.30 and 0.33, respectively). Sedation, weight increase, and hypothyroidism occurred more frequently in the quetiapine group, as did discontinuations due to adverse events. The incidence and incidence density of a single emergent blood glucose value ≥126 mg/dl were higher in the quetiapine group (12.6% versus 5.4%; 18.44 versus 9.56 patients per 100 patient-years). Adverse events were generally consistent with the known tolerability profile of quetiapine. Conclusions: In patients stabilized on quetiapine plus lithium or divalproex, continued treatment was associated with a significant risk reduction in the time to recurrence of any mood event compared with placebo and lithium or divalproex.

Bipolar I disorder is a lifelong psychiatric condition characterized by episodes of mania, usually interspersed with episodes of major depression (1) . In recent years, more attention has been focused on long-term management of symptoms. While the need for continuous treatment of patients with bipolar I disorder was established a number of years ago (2) , the significant consequences of multiple episodes (3 , 4) , as well as the functional impact and increased morbidity and mortality associated with inadequate treatment, are now better appreciated (5 , 6) . In fact, recent episodes may be among the strongest predictors of new mania or depression (7) . Therefore, the study of medication that may delay or prevent recurrence is crucial to improving outcomes and quality of life for patients with bipolar disorder.

There have been relatively few controlled long-term studies of maintenance therapy, and especially the role of combination treatment, in patients with bipolar disorder (8) . Current guidelines for maintenance treatment recommend in some circumstances the use of atypical antipsychotics in combination with lithium or divalproex or with an antidepressant (8 – 11) . These recommendations are made with the caveat that more controlled trials are needed, particularly for combination therapies.

This study (Trial 127), conducted at multiple sites across North America, was performed in parallel with an international study (Trial 126) of similar design and size that comprised sites in 18 countries (12) . Both studies evaluated the long-term efficacy and safety of quetiapine given in combination with lithium or divalproex in the prevention of mood events in patients with bipolar I disorder. The study tested the hypothesis that the combination of quetiapine and lithium or divalproex would be better than lithium or divalproex monotherapy for preventing recurrence of mood events.

Method

Study Design

This was a multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, double-blind study comparing quetiapine plus lithium or divalproex and placebo plus lithium or divalproex in the maintenance treatment of adult patients with bipolar I disorder for up to 104 weeks. A prerandomization phase of 12–36 weeks included an open-label acute treatment period during which patients had to achieve clinical stability for 12 weeks to enter the randomized maintenance phase of up to 104 weeks. The study was conducted at 127 centers in the United States and Canada between March 2004 and December 2006. The study protocol was compliant with the current amendment of the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization/Good Clinical Practice guidelines. A written informed consent form approved by the relevant institutional review boards was signed by all patients.

Patient Population

The key inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients entering the prerandomization and randomization phases are listed in Figure 1 . Patients were eligible for inclusion regardless of whether their index episode was manic, depressed, or mixed.

a Assessed at a minimum of four consecutive visits spanning at least 12 weeks in the prerandomization phase, with the allowance of a single excursion (Young Mania Rating Scale and/or Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total scores of 13 or 14; except at the last of these consecutive visits).

For each potential participant, a history of mania or depression was determined clinically by the clinical investigator, who was strongly encouraged to obtain medical documentation of support. If such documentation was not available, investigators could use their medical judgment; a history of hospitalization was not required.

To qualify for the randomized treatment phase, patients had to have received treatment with quetiapine and either lithium or divalproex for at least 12 weeks during the prerandomization phase and to have reached clinical stability, defined as total scores ≤12 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (13) and Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (14) , assessed on at least four consecutive visits spanning at least 12 weeks in the prerandomization phase, with the allowance of a single excursion of the YMRS and/or MADRS total scores to 13 or 14 (except at the last of these consecutive visits).

Study Medication

In the prerandomization phase, patients started on or continued with flexibly dosed quetiapine (400–800 mg/day in divided doses, with a recommended target dose of 600 mg/day). Doses were adjusted to maximize efficacy and tolerability. Patients also started or continued an oral dose of open-label lithium or divalproex, which was chosen by the investigator. During this phase, doses were adjusted to achieve target trough serum concentrations of 0.5–1.2 meq/liter for lithium and 50–125 μg/ml for divalproex.

At randomization, patients received either quetiapine plus lithium or divalproex or placebo plus lithium or divalproex twice daily in a flexible, double-blind manner, by replacing the open-label quetiapine 100-mg tablets with 100-mg tablets of blinded investigational product at a rate of one tablet every 2 days. The dose of quetiapine could be adjusted as clinically indicated within the dosage range of 400–800 mg/day. Lithium or divalproex doses were maintained within the previous trough serum ranges and were not adjusted unless tolerability worsened or serum levels were outside target concentrations. Low dosages of zolpidem (up to 10 mg/day) for insomnia, lorazepam (up to 2 mg/day) for anxiety, and anticholinergic medications for extrapyramidal symptoms were permitted throughout the study.

During both the prerandomization and randomized treatment phases, patients were allowed to continue using previous medications for nonpsychiatric medical illnesses, as well as oral contraceptives. In the prerandomization phase, benzodiazepines and other psychoactive drugs, including antidepressants, anxiolytics, stimulants, and sedatives, could be used as clinically indicated up to the last 12 weeks prior to randomization. The use of depot antipsychotics was not permitted during the last 16 weeks prior to randomization.

Outcome Measures

The primary efficacy measure was the time to recurrence of any mood event, defined as any of the following: initiation of any medication to treat mixed, manic, or depressive symptoms, including an antipsychotic, antidepressant, or mood-stabilizing agent other than lithium or divalproex or an anxiolytic other than lorazepam; psychiatric hospitalization; YMRS or MADRS total scores ≥20 at two consecutive assessments; or discontinuation from the study because of a mood event (as determined by the investigator). YMRS and MADRS scores were recorded at each visit. Visits were conducted at weekly intervals for weeks 0–2, every 2 weeks for weeks 2–8, at monthly intervals for weeks 8–52, and every 2 months thereafter.

Secondary efficacy measures included the time to recurrence of mania or depression. Mixed events with predominantly manic or depressive symptoms were classified as manic and depressed events, respectively, as judged by the clinical investigator. The overall level of patient acceptance of quetiapine compared with placebo was assessed by examining the time to all-cause treatment discontinuation. Other secondary outcome measures included severity of manic, depressive, and psychotic symptoms, as quantified by scores on the YMRS, the MADRS, the Clinical Global Impression scale modified for bipolar disorder (CGI-BP) (15) , and the positive subscale of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (16) . The Sheehan Disability Scale (17) was used to assess functioning, and quality of life was measured using the Psychological General Well-Being Index (18) .

Safety Endpoints

The occurrence of adverse events (overall and drug-related) and withdrawals due to adverse events were recorded at each assessment. Adverse events were classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities nomenclature. Additional safety endpoints included laboratory test results (assessed at enrollment, at randomization, and at regular intervals throughout the study), vital signs, weight, body mass index (BMI), ECG results, and physical examination results. Results for glucose and lipid parameters were grouped in two ways: the first included all samples regardless of fasting status, and the second included a subset of samples that were considered to be patient self-reported fasting (at least 8 hours from time of last meal to blood sampling, although this did not exclude the possibility of fluid or other additional caloric intake). Changes in serum glucose levels were also evaluated for patients with diabetes (in this study defined as a fasting glucose level ≥126 mg/dl or a nondocumented fasting glucose level ≥200 mg/dl at randomization, a history of diabetes, or glycosylated hemoglobin [HbA1c] above 7.5% at randomization), or diabetic risk factors, which included a fasting glucose level ≥100 and <126 mg/dl at randomization, a history of gestational diabetes, or a BMI ≥35. These measures were used not as diagnostic categories but for the purposes of data analysis of patient subgroups. Adverse events potentially associated with diabetes (an aggregated set of adverse events, including hyperglycemia, diabetes mellitus, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, increased blood insulin, diabetic ketoacidosis, polydipsia, thirst, and polyuria) were also recorded. Extrapyramidal symptoms were assessed with the Simpson-Angus Scale (19) , the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (20) , and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (21) . The open-label safety population included all patients who entered the prerandomization phase and received at least one dose of study medication.

Statistical Analysis

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyze the time to any mood event by estimating the hazard ratio of recurrence between treatment groups. The time to an event was censored when a patient discontinued from or completed the study without experiencing a manic, depressed, or mixed event. Hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined for the quetiapine versus placebo treatment groups by calculating the hazard rate, the probability that if a mood event has not occurred it will occur during the next time interval, divided by the length of that interval. The hazard ratio gives an estimate of the relative risk of a mood event and provides an assessment of treatment efficacy by comparing time to an event. A priori, the study concluded when 227 mood events occurred. Thus, the overall time in the study varied between patients. The sample size was based on achieving an assumed hazard ratio of 0.65 for quetiapine combination treatment versus placebo combination treatment. To provide 90% power with a two-tailed test at a significance level of 0.05, 227 patients with a documented recurrence of a mood event were required.

Time to all-cause discontinuation was assessed with the same Cox proportional hazards model. Scores on the YMRS, MADRS, CGI-BP, PANSS positive subscale, and Psychological General Well-Being Index were analyzed using a mixed-model repeated-measures analysis of all assessments from randomization up to, but excluding, the first mood event. The assigned co-treatment (either lithium or divalproex) and treatment group were included as fixed-effect covariates. The Sheehan Disability Scale total score was summarized for each patient using the mean change from baseline across all assessments from randomization up to, but excluding, the first mood event. These mean changes were analyzed using analysis of covariance with the baseline Sheehan Disability Scale total score, assigned co-treatment (lithium or divalproex), and treatment as fixed effects. A stepwise sequential procedure was employed throughout the confirmatory part of the study to ensure a multiple level of significance of 0.05. The time to a mood event, time to a manic event, time to a depressed event, and mean change in Sheehan Disability Scale total score were tested sequentially.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize changes from baseline in laboratory test results, weight changes, vital signs, ECG results, and scores on the Simpson-Angus Scale, Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale, and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. Statistical analysis of safety endpoints was not planned in the study protocol. Incidence densities of increases in blood glucose to hyperglycemic levels were calculated ([total number of patients with a glucose value ≥126 mg/dl emerging during randomized treatment/total patient-years of exposure] × 100), where the time until the first value ≥126 mg/dl (or until the last dose for patients with no values ≥126 mg/dl) was calculated for each patient.

Results

Of the 1,953 patients enrolled in the study, 1,325 (67.8%) discontinued prior to the randomized treatment period. Of the 628 patients randomly assigned to double-blind treatment, 623 received at least one dose of study medication and were included in the intent-to-treat study population ( Figure 2 ). The quetiapine and placebo groups were generally similar with regard to demographic characteristics and illness severity at randomization ( Table 1 ).

a “Completed treatment” means completing a maximum of 104 weeks of randomized treatment or remaining on the assigned treatment until the study was terminated.

During randomized treatment, the mean of the individual median daily doses of quetiapine was 519 mg and the mean duration of quetiapine exposure was 240 days. The mean duration of exposure to placebo was 178 days. During the randomized phase, 42.5% of patients were treated with lithium and 57.5% of patients were treated with divalproex. The median serum concentrations of lithium for the quetiapine and placebo groups were 0.74 and 0.71 meq/liter, respectively; the median serum concentrations of divalproex were 68.91 and 71.38 μg/ml, respectively.

Overall, 28.3% (176/623) of patients reached the end of the study at 104 weeks of treatment or were still undergoing treatment when the study was terminated: 35.5% (110/310) of the quetiapine group and 21.1% (66/313) of the placebo group ( Figure 2 ).

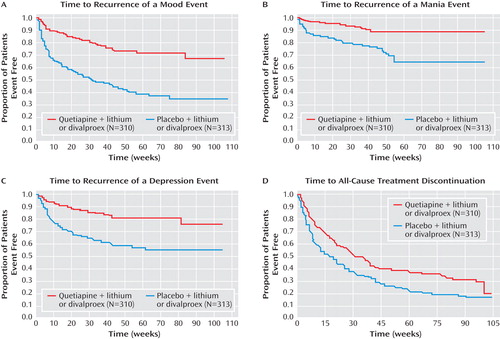

Time to Recurrence of a Mood Event

The quetiapine treatment combination was significantly more effective than the placebo treatment combination in increasing the time to recurrence of any mood event ( Figure 3 ). The hazard ratio for the time to recurrence of a mood event was 0.32 (95% CI=0.24–0.42, p<0.0001), a risk reduction of 68%. Fewer patients in the quetiapine group experienced mood events (20.3% [63/310], versus 52.1% [163/313] in the placebo group). To reduce the impact of potential discontinuation effects on the analyses and conclusions, an additional post hoc analysis was performed in which data were censored to exclude events occurring within the first 4 weeks of randomized treatment. The hazard ratio for the time to recurrence of a mood event was 0.33 (95% CI=0.23–0.47, p<0.0001), a risk reduction of 67%.

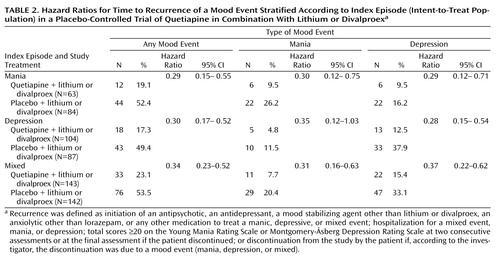

Secondary analyses of patient subgroups demonstrated that time to recurrence of a mood event was not dependent on the nature of the index episode ( Table 2 ), lithium or divalproex co-treatment, or rapid cycling (see Table S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article).

Secondary Efficacy Variables

The quetiapine combination treatment was significantly more effective than the placebo combination treatment in increasing the time to recurrence of a mania or a depression event ( Figure 3 ). There was a 70% risk reduction (hazard ratio=0.30; 95% CI=0.18–0.49, p<0.0001) in the time to recurrence of a mania event and a 67% risk reduction in the time to recurrence of a depression event (hazard ratio=0.33; 95% CI=0.23–0.48, p<0.0001). Censoring of data to exclude events occurring within 4 weeks of randomization resulted in hazard ratios of 0.33 (95% CI=0.18–0.61, p<0.001) and 0.33 (95% CI=0.22–0.51, p<0.0001) for mania and depression events, respectively.

As observed for the primary efficacy measure, hazard ratios for the time to recurrence of mania or depression events associated with quetiapine treatment were low and independent of the nature of the index episode ( Table 2 ). The time to all-cause treatment discontinuation during randomized treatment was longer in the quetiapine group compared with the placebo group ( Figure 3 ). Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to 50% all-cause discontinuation were 212 days for the quetiapine group and 114 days for the placebo group.

Quetiapine combination treatment was associated with a significantly lower severity of interepisode mania and depression symptoms during the period of remission than placebo combination treatment (p≤0.001), as measured by the estimated difference in total mean scores on the YMRS, MADRS, and CGI-BP (see Table S2 in the online data supplement). The change in the severity of interepisode psychotic symptoms, as measured by the PANSS positive subscale, was not significantly different between the quetiapine and placebo treatment groups (difference between groups=–0.18, p=0.0521). This trend between groups favored quetiapine treatment. There were no significant differences between groups in interepisode change in functioning (Sheehan Disability Scale) or quality of life (Psychological General Well-Being Index).

Safety and Tolerability

Table 3 summarizes adverse events during the prerandomization (all patients enrolled) and randomized treatment (intent-to-treat population) phases of the study; reasons for premature discontinuation from the study are presented in Figure 2 .

During the prerandomization phase, adverse events were reported by 85.2% (1,652/1,938) of patients (open-label safety population), and 20.3% (394/1,938) of patients in the open-label safety population experienced adverse events that were considered to have led to withdrawal from the study. Sedation was the only adverse event with a frequency ≥5% that prompted discontinuation during prerandomization treatment with quetiapine; discontinuation because of sedation was reported in 128 (6.6%) patients. Emergent adverse events judged by the investigator to have been drug-related were reported by 71.6% (1,387/1,938) of the open-label safety population.

During the randomized treatment phase, a similar proportion of patients in both groups reported any adverse event (78.4% [243/310] in the quetiapine group and 76.7% [240/313] in the placebo group). Adverse events leading to discontinuation were reported in 11.3% (35/310) and 2.6% (8/313) of patients in the quetiapine and placebo groups, respectively. No single adverse event leading to discontinuation was reported at a frequency ≥5% during the randomized treatment phase. Serious adverse events were reported by 18 (5.8%) patients in the quetiapine group and seven (2.2%) in the placebo group. Emergent adverse events judged by the investigator to have been drug related were reported by 40.0% (124/310) and 32.3% (101/313) of patients in the quetiapine and placebo groups, respectively. Only three adverse events were found to have significantly greater occurrences in the quetiapine group compared with the placebo group during the randomized treatment phase—sedation, weight increase, and hypothyroidism. Insomnia was significantly greater in the placebo group compared with the quetiapine group. One patient in the quetiapine group committed suicide 24 days after discontinuing the study; the investigator attributed no study cause to the suicide.

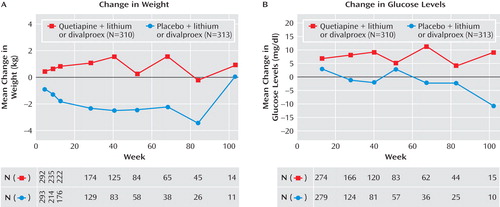

During the prerandomization phase of the trial, a mean weight increase of 3.1 kg was reported between enrollment and randomization, with 23.1% of patients experiencing an increase in weight ≥7%. During the randomized treatment phase, patients in the quetiapine group had a mean weight gain of 0.5 kg, whereas those in the placebo group lost an average of 2.0 kg. In the quetiapine group, those receiving divalproex (N=179) gained more weight than those receiving lithium (N=131) during the randomized treatment phase (0.79 versus 0.01 kg, respectively). The proportions of randomized patients experiencing ≥7% increases in weight were 11.5% and 3.7% for the quetiapine and placebo groups, respectively. In the quetiapine group, the total mean weight gain from enrollment to the end of the randomized treatment phase was 5.3 kg. Figure 4 shows the mean changes in weight occurring over the course of the study.

a Observed case data do not reflect mean changes at end of treatment.

Changes in glucose, HbA1c, insulin, and lipid parameters recorded over the course of the study are presented in Table 4 and Figure 4 . For patients in the quetiapine group, the mean change from enrollment to end of randomized treatment was 6.61 mg/dl for glucose level and 35.40 mg/dl for triglyceride level. The incidence of a single emergent blood glucose value ≥126 mg/dl was higher in the quetiapine group than in the placebo group (12.6% versus 5.4%), as was the incidence density (18.44 versus 9.56 patients per 100 patient-years). The incidence of adverse events potentially associated with diabetes (as defined in the Method section) was assessed in both the prerandomization (2.6%) and randomized treatment phases (5.2% and 1.6% for the quetiapine and placebo groups, respectively).

Adverse events potentially associated with extrapyramidal symptoms (e.g., akathisia, cogwheel rigidity, restlessness, and tremor) were reported by 15.5% of patients receiving quetiapine in the prerandomization phase and by 11.0% and 9.6% of patients in the quetiapine and placebo groups, respectively, in the randomized treatment phase. Most patients in both treatment groups improved over time or had no change in scores on the Simpson-Angus Scale, Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale, and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale from randomization to last assessment. The proportion of patients with worsening scores on these scales was low and was similar between treatment groups.

Discussion

In this study of patients with bipolar I disorder who were stabilized on combination treatment with quetiapine plus lithium or divalproex, continuation of this treatment significantly increased the time to recurrence of any mood event compared with placebo plus lithium or divalproex. The risk reduction was 68% for time spent in the study before any mood event was reported, with risk reductions of 70% for mania and 67% for new depression. These reductions were independent of the nature of the index episode or whether the patient was receiving lithium or divalproex concomitantly, supporting a broad efficacy of quetiapine in delaying the time to recurrence of a mood event. All-cause termination favored the quetiapine combination treatment, with the mean time in study of 240 days for the quetiapine group and 178 days for the placebo group. In the randomized treatment phase, 28% of patients completed treatment (either the maximum of 104 weeks or until study termination), with 35% of those in the quetiapine group and 21% of those in the placebo group.

Many studies assessing the effectiveness of therapies for maintenance treatment have required a period of acute clinical improvement, sometimes followed by a brief period of stabilization, and then randomization. Such studies are not reflective of real-world treatment, where patients are stabilized for a number of weeks on combination treatment and then efforts are made to simplify the regimen. In the present study, patients had to achieve 12 weeks of clinical stability on combination therapy before randomization to maintenance therapy, a design reflecting a more real-world approach to recurrence prevention (22 – 24) . With the strict criteria used for clinical stabilization, coupled with the longest duration required for stabilization before randomization to date of any maintenance study in bipolar disorder, it was to be expected that fewer patients would meet these criteria than in earlier studies, for a variety of reasons, including inability to stabilize and intolerance of combination treatment. Tolerability is an important concern in choice of maintenance treatments, because many patients with bipolar disorder are nonadherent to prescribed medications, and adverse effects provide a justification for inconsistent use (25 – 28) . For patients for whom quetiapine plus lithium or divalproex was effective and tolerated in the acute phase, continued treatment with this combination during maintenance therapy was beneficial in sustaining response and preventing recurrence of symptoms of both mania and depression.

The development of effective maintenance strategies is a core treatment need for patients with bipolar disorder. The severe and persistent nature of bipolar disorder is recognized, yet with effective and sustained treatment, recurrences and the overall impact of the illness may be lessened dramatically. A fairly long period of stabilization in this study (12 weeks) ensured that patients were entering the maintenance phase of treatment, in which usual clinical practice includes recommendations to simplify and change medications (8 – 11) . Relapse implies new or worsening symptoms during a period of continuing symptoms or in close proximity to an acute episode (e.g., 4–8 weeks later), and recurrence is defined by a period of stabilization significantly further removed from an acute episode and the emergence of new mood symptoms (e.g., 8–12 or more weeks from the episode). Relapses occurring in proximity to acute episodes cannot be viewed as new episodes, and study designs using such a definition do not allow for assessment of prevention of new episodes. Hence, the present study required a conservative 12 weeks of stabilization before randomization.

Additional analysis was carried out to further clarify the impact of medication changes and to ensure that recurrence and not relapse was being studied. Because of the possible risk of discontinuation effects for patients not fully stabilized at randomization, we selected a cut point of 4 weeks in order to capture immediate discontinuation effects (2 , 29) . We found that risk reductions were similar to those noted above when patients experiencing a mood event within the first 4 weeks following randomization were excluded from the analysis.

Other study designs were considered in developing this study protocol (30 , 31) , including stabilization on lithium or divalproex only, followed by addition of quetiapine or placebo. The design in this study, in which stabilization was achieved with combination treatment, after which the medication regimen was simplified, was chosen because of its approximation to real-world practice for patients with bipolar disorder. This design creates an enriched sample of patients who are responsive to and tolerant of the combination of quetiapine and lithium or divalproex. An alternative could be stabilization on any combination of medications, transition to the medications of interest, requirement for an additional period of stabilization, and then randomization of half of the participants to placebo. This would theoretically have been an interesting approach, but would likely leave a sample too small for meaningful analysis. Finally, a few studies have tried to use a purely prophylactic design, in which patients with a history of a highly relapsing course of illness are enrolled during remission and randomized to adjunctive drug or placebo (32 , 33) . The issue of patient burden in long-term treatment trials was eloquently discussed in a review of one such study (31) .

The development of long-term trials is complex. Numerous decisions must be made on entry, cut points, and termination. Patient safety and study burden must be considered in the design. In this study, a fairly rigorous definition of stabilization was required before patients could enter the randomization phase: both depressive and manic symptoms had to be below syndromal level. In fact, notable improvement was seen for those patients who stabilized, and entry levels of depression and mania were in the minimal symptom range. Discontinuation due to a mood event could occur by a number of routes, including clinician judgment, addition of new medications for an emerging episode, or a score ≥20 on the MADRS or YMRS. Although a score ≥20 on the YMRS could be viewed as high for as an outcome measure, it was set at this level to improve the reliability of the measure, keeping in mind, as noted, that a number of routes of discontinuation were allowed. This same discussion would apply as well to depression recurrence assessment using the MADRS. Moreover, using what may be considered relatively high cutoff scores also limits the risk of incorrectly categorizing a patient as having a recurrence, while still supporting clinical judgment as an option to discontinue any patient viewed as experiencing symptoms consistent with a recurrence.

There were no differences in interepisode functioning and quality-of-life measures between the quetiapine and placebo groups, despite the long observation period. People with bipolar disorder often have impaired psychosocial functioning (34 – 37) , and some degree of functional impairment is evident even after remission of symptoms. MacQueen and colleagues reported that up to 60% of individuals with bipolar disorder do not regain full functioning in occupational and social domains (38) . It is possible that the potential for functional improvement is optimized if patients maintain a sustained remission over longer-term follow-up, and with psychosocial support (39) .

The significant delay to recurrence with quetiapine plus lithium or divalproex in this study regardless of type of mood event or index episode is notable. An earlier long-term but uncontrolled study did not support significant prevention of depressive symptoms with clozapine (40) , and other controlled studies with atypical antipsychotics did not enroll patients who had an index episode of depression, only manic or mixed episodes (41) . In the present study, quetiapine with lithium or divalproex was more effective in preventing episodes of all types than placebo with lithium or divalproex. Well-controlled studies of quetiapine monotherapy for recurrence prevention would further clarify the strength of this effect.

The rate of emergent adverse events for the randomized treatment phase was lower than that for the prerandomization phase, which suggests that adverse events emerge within weeks of treatment initiation and are less likely to emerge thereafter. A post hoc statistical analysis of tolerability across the two treatment groups indicated that sedation, weight gain, and hypothyroidism were significantly greater in the quetiapine group than in the placebo group. However, these results must be interpreted with caution as the analyses were performed without correcting for multiple comparisons, which increases the likelihood of a type I statistical error.

The total mean weight gain from enrollment to the end of the randomized treatment phase was 5.3 kg in the group taking quetiapine plus lithium or divalproex. This is a greater degree of weight gain than that reported in a recent review of patients treated with quetiapine in schizophrenia clinical trials (mean weight gain of 3.2 kg over 52 weeks of treatment) (42) . Given that patients in the placebo group lost an average of 2.0 kg while those in the quetiapine group gained a small amount of weight at the dosages used (400–800 mg/day of quetiapine), there is the potential for weight gain with longer-term quetiapine combination therapy.

In the quetiapine group, the mean change in glucose level from enrollment to the end of the randomized treatment phase was 6.61 mg/dl. The incidence and incidence density of a single emergent blood glucose value ≥126 mg/dl was higher in the quetiapine group than in the placebo group (12.6% versus 5.4% and 18.44 versus 9.56 patients per 100 patient-years, respectively). However, blood samples could not be confirmed as fasting samples despite a patient-reported 8-hour interval since the last meal, as patients could have had other caloric intake during that interval. The study was not designed to identify or confirm the emergence of diabetes on the basis of fasting blood glucose assessments, which require confirmation of fasting blood glucose values ≥126 mg/dl within a few days (43) . In this study, blood samples were taken 12 weeks apart with no requirement for repeated testing after abnormal results. However, the data suggest that increases in glucose and triglyceride levels may occur in some patients taking quetiapine, and it is important that this issue receive further focused study. Compared with placebo, changes in blood glucose levels during randomized treatment with quetiapine were most pronounced in patients categorized as diabetic on the basis of historical information and other data collected at randomization. Similar to glucose changes, changes in HbA1c and insulin were largest in patients with likely diabetes, with smaller changes observed in patients showing diabetic risk factors, while nondiabetic patients remained relatively stable (data not shown). Overall, a significantly greater change in HbA1c values was observed in the quetiapine group compared with the placebo group during the randomized treatment phase. Over long-term treatment, consideration should be given to assessment of metabolic parameters. These data will be needed to fully elucidate the risk-benefit ratio of long-term use of quetiapine in combination therapy.

Limitations of this study include the fact that the sample may not have reflected a usual outpatient setting sample given the exclusion criteria and the need for patients to stabilize and sustain stabilization for a number of months. The metabolic impact of quetiapine in combination treatment was not a special focus of the design, and thus further study will be needed to fully assess the relative risk-benefit ratio of this treatment.

This study supports the efficacy of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex to prevent recurrence of mood episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder. This is the first and only atypical antipsychotic to show efficacy, regardless of whether the index episode was manic or depressed, in preventing recurrence to either pole, an effect replicated in Trial 126 (12) . For patients who respond to quetiapine plus lithium or divalproex in acute treatment, continued treatment with the combination appears to be beneficial as maintenance therapy. Combination treatment is the basis of treatment for many patients with bipolar I disorder, and decisions regarding long-term use of quetiapine should consider individual patient risk for obesity, diabetes, and other comorbid medical conditions.

1. Glick ID, Suppes T, DeBattista C, Hu RJ, Marder S: Psychopharmacologic treatment strategies for depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:47–60Google Scholar

2. Suppes T, Baldessarini RJ, Faedda GL, Tohen M: Risk of recurrence following discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1082–1088Google Scholar

3. Begley CE, Annegers JF, Swann AC, Lewis C, Coan S, Schnapp WB, Bryant-Comstock L: The lifetime cost of bipolar disorder in the US: an estimate for new cases in 1998. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19:483–495Google Scholar

4. Swann AC, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Dilsaver SC, Morris DD: Mania: differential effects of previous depressive and mania episodes on response to treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 101:444–451Google Scholar

5. Martinez-Aran A, Vieta E, Torrent C, Sanchez-Moreno J, Goikolea JM, Salamero M, Malhi GS, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Daban C, Alvarez-Grandi S, Fountoulakis K, Kaprinis G, Tabares-Seisdedos R, Ayuso-Mateos JL: Functional outcome in bipolar disorder: the role of clinical and cognitive factors. Bipolar Disord 2007; 9:103–113Google Scholar

6. Angst F, Stassen HH, Clayton PJ, Angst J: Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34–38 years. J Affect Disord 2002; 68:167–181Google Scholar

7. Kessing LV, Hansen MG, Andersen PK, Angst J: The predictive effect of episodes on the risk of recurrence in depressive and bipolar disorders: a life-long perspective. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004; 109:339–344Google Scholar

8. Suppes T, Dennehy EB, Hirschfeld RM, Altshuler LL, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Crismon ML, Ketter TA, Sachs GS, Swann AC: The Texas Implementation of Medication Algorithms: update to the algorithms for the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:870–886Google Scholar

9. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, Parikh SV, MacQueen G, McIntyre RS, Sharma V, Beaulieu S: Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8:721–739Google Scholar

10. Grunze H, Kasper S, Goodwin G, Bowden C, Moller HJ: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders, part III: maintenance treatment. World J Biol Psychiatry 2004; 5:120–135Google Scholar

11. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(April suppl)Google Scholar

12. Vieta E, Suppes T, Eggens I, Persson I, Paulsson B, Brecher M, on behalf of the Trial 126 study investigators: Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex for maintenance of patients with bipolar I disorder (international trial 126). J Affect Disord 2008; 109:251–263Google Scholar

13. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity, and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429–435Google Scholar

14. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Google Scholar

15. Spearing MK, Post RM, Leverich GS, Brandt D, Nolen W: Modification of the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): the CGI-BP. Psychiatry Res 1997; 73:159–171Google Scholar

16. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261–276Google Scholar

17. Sheehan DV: The Anxiety Disease. New York, Scribner, 1983Google Scholar

18. Dupuy HJ: The Psychological General Well-Being (PGWB) Index, in Assessment of Quality of Life in Clinical Trials of Cardiovascular Therapies. Edited by Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Furberg CD, Elinson J. New York, Le Jacq Publishing, 1984, pp 170–183Google Scholar

19. Simpson GM, Angus JWS: A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 212:11–19Google Scholar

20. Barnes TR: A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:672–676Google Scholar

21. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 534–537Google Scholar

22. Tohen M, Greil W, Calabrese JR, Sachs GS, Yatham LN, Oerlinghausen BM, Koukopoulos A, Cassano GB, Grunze H, Licht RW, Dell’Osso L, Evans AR, Risser R, Baker RW, Crane H, Dossenbach MR, Bowden CL: Olanzapine versus lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: a 12-month, randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1281–1290Google Scholar

23. Tohen M, Calabrese JR, Sachs GS, Banov MD, Detke HC, Risser R, Baker RW, Chou JC-Y, Bowden CL: Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine as maintenance therapy in patients with bipolar I disorder responding to acute treatment with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:247–256Google Scholar

24. Keck PE Jr, Calabrese JR, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Carlson BX, Rollin LM, Marcus RN, Sanchez R; Aripiprazole Study Group: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 26-week trial of aripiprazole in recently manic patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:626–637Google Scholar

25. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Warnock A, Bell A, Young AH: Effectiveness of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics in the maintenance phase of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Bipolar Disord 2007; 9:394–412Google Scholar

26. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Bourne ML, West SA: Compliance with maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997; 33:87–91Google Scholar

27. Hassan M, Madhavan SS, Kalsekar ID, Makela EH, Rajagopalan K, Islam S, Kavookjian J, Miller LA: Comparing adherence to and persistence with antipsychotic therapy among patients with bipolar disorder. Ann Pharmacother 2007; 41:1812–1818Google Scholar

28. Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow FC, Ganoczy D, Ignacio RV: Treatment adherence with antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8:232–241Google Scholar

29. Faedda GL, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Suppes T, Tohen M: Outcome after rapid vs gradual discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:448–455Google Scholar

30. Calabrese JR, Goldberg JF, Ketter TA, Suppes T, Frye M, White R, DeVeaugh-Geiss A, Thompson TR: Recurrence in bipolar I disorder: a post hoc analysis excluding relapses in two double-blind maintenance studies. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:1061–1064Google Scholar

31. Bowden CL, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Morris D, Petty F, Hirschfeld RM, Gyulai L: Maintenance clinical trials in bipolar disorder: design implications of the divalproex-lithium-placebo study. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997; 33:693–699Google Scholar

32. Vieta E, Goikolea JM, Martínez-Arán A, Comes M, Verger K, Masramon X, Sanchez-Moreno J, Colom F: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of adjunctive gabapentin for bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:473–477Google Scholar

33. Vieta E, Cruz N, García-Campayo J, de Arce R, Manuel Crespo J, Vallès V, Pérez-Blanco J, Roca E, Manuel Olivares J, Moríñigo A, Fernández-Villamor R, Comes M: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled prophylaxis trial of oxcarbazepine as adjunctive treatment to lithium in the long-term treatment of bipolar I and II disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2008; 17:1–8Google Scholar

34. Bauer MS, Kirk GF, Gavin C, Williford WO: Determinants of functional outcome and healthcare costs in bipolar disorder: a high-intensity follow-up study. J Affect Disord 2001; 65:231–241Google Scholar

35. Altshuler LL, Gitlin MJ, Mintz J, Leight KL, Frye MA: Subsyndromal depression is associated with functional impairment in patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:807–811Google Scholar

36. Calabrese JR, Hirschfeld RM, Reed M, Davies MA, Frye MA, Keck PE, Lewis L, McElroy SL, McNulty JP, Wagner KD: Impact of bipolar disorder on a US community sample. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:425–432Google Scholar

37. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Leon AC, Solomon DA, Coryell W, Maser JD, Keller MB: Psychosocial disability in the course of bipolar I and II disorders: a prospective, comparative, longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:1322–1330Google Scholar

38. MacQueen GM, Young LT, Joffe RT: A review of psychosocial outcome in patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001; 103:163–170Google Scholar

39. Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Kogan JN, Sachs GS, Thase ME, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Ostacher MJ, Patel J, Thomas MR, Araga M, Gonzalez JM, Wisniewski SR: Intensive psychosocial intervention enhances functioning in patients with bipolar depression: results from a 9-month randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1340–1347Google Scholar

40. Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, Carmody T, Kraemer H, Rush AJ: Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1164–1169Google Scholar

41. Vieta E, Rosa AR: Evolving trends in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry 2007; 8:4–11Google Scholar

42. Brecher M, Leong RW, Stening G, Osterlin-Koskinen L, Jones AM: Quetiapine and long-term weight change: a comprehensive data review of patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:597–603Google Scholar

43. American Diabetes Association: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2006; 29(suppl 1):S43–S48Google Scholar