Self and Other in Schizophrenia: A Cognitive Neuroscience Perspective

Abstract

Objective: Recent basic science data indicate that in healthy individuals, self-referential processing and social cognition rely on common neural substrates. The authors assessed self-referential source memory and social cognition in a large sample of schizophrenia outpatients and healthy comparison subjects in order to compare how these critical processes are associated in the two groups. Method: Ninety-one schizophrenia outpatients and 30 healthy comparison subjects were assessed on measures of basic social cognition and source memory for previously learned word items: self-generated, externally presented, and new words. Partial correlations and multiple regression analysis were used to test the association between social cognition measures and source memory performance and the contributions of source memory and general cognitive abilities to a social cognition composite score. Results: Schizophrenia patients demonstrated significantly lower source memory for self-generated items (self-referential source memory) relative to comparison subjects but showed intact external source memory. In both groups, self-referential source memory and social cognition showed strong correlations. When the effects of general cognitive abilities were controlled for, these correlations were attenuated in the schizophrenia patients. Regression analysis revealed discrepancies between groups in the cognitive functions contributing to social cognition performance. Conclusions: Impaired self-referential source memory represents a unique cognitive deficit in schizophrenia. Moreover, the strong association between self-referential source memory and social cognition seen in healthy subjects is reduced in schizophrenia and is moderated by general cognitive abilities. Impairments in the neurocognitive system that underlies both self-referential and social cognition provide a parsimonious explanation for the disturbances in the sense of self and other that characterize schizophrenia.

The difficulty the patient experiences in dealing with other human beings … is the external counterpart of what goes on inside himself.… [A] disturbed inner life causes alterations in relating to others.

Deficits in social cognitive abilities and interpersonal functioning, which have been described and interpreted for over 150 years, are among the most dramatic features of schizophrenia and are a key determinant of functional outcome. Yet the component processes that contribute to social cognitive impairments in schizophrenia are not fully understood (2) . The well-known deficits in general neurocognition that characterize this disorder show only moderate bivariate correlations with performance on tasks involving emotion identification, social perception, and mentalizing about the states of others (3 – 5) . Moreover, as noted by the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia Committee (2) , aspects of social cognition have a distinct neural substrate from nonsocial cognitive domains, such as attention, memory, and executive functions (6) .

Given that the processing of social information involves distinct neural systems, what specific operations might contribute to the impaired social cognitive performance seen in schizophrenia? Interestingly, recent functional MRI (fMRI) evidence from healthy subjects suggests that a common neural substrate, the medial prefrontal cortex, is recruited during both social cognition tasks and self-referential processing (7) . Specifically, the medial prefrontal cortex shows relative activation during a wide range of social cognitive processes, such as viewing faces, social scenes, and social interactions (8 – 10) and mentalizing about the thoughts, intentions, or feelings of others (11) . Subregions of the medial prefrontal cortex also show activation in response to self-referential cognitive processes: during self-referential memory (12 , 13) and during reflection on one’s own personality characteristics and emotional states (14 – 16) .

These imaging findings suggest that there is a fundamental relationship between social and self-referential cognition, and they raise the intriguing possibility that alterations in this association may play a role in schizophrenia. Yet, with few exceptions, the evidence that self-referential and social cognitions share common processes is based on comparisons across imaging studies of healthy subjects rather than investigations of both sets of operations within the same sample of subjects (7) . Furthermore, these questions have not been systematically broached in schizophrenia patients, even though cognitive theory and psychoanalytic thinkers have for decades posited cognitive biases in the internal representation of self and other as being central to models of severe psychopathology (17 , 18) .

Guided by neuroimaging findings in healthy individuals, and having recently demonstrated in an fMRI experiment (19) that subjects with schizophrenia do not show the normal activation of the medial prefrontal cortex seen in healthy subjects during a self-referential memory task, we were prompted to ask: Is it possible that the deficits in social cognition that are observed in schizophrenia are related to impairments in self-referential processing?

We thus sought to investigate, in a large sample of stable, well-characterized outpatients, the behavioral relationship between performance on a set of basic social cognition measures—facial memory, facial emotion identification, and vocal prosody recognition—and a specific emotionally neutral self-referential cognitive process under study in our laboratory: source memory for self-generated information (20) . We defined social cognition by performance on basic tasks of emotion recognition and social perception that are known to be associated with functional outcome in schizophrenia (and that contribute to, and can be contrasted with, more complex constructs, such as mentalizing about others) (2 , 11) .

In order to proceed with this line of inquiry, however, we were first obliged to demonstrate that self-referential source memory in schizophrenia is a unique cognitive process, suitable for use as a probe into social cognition and not merely a reflection of an overall problem in source memory or other more general cognitive abilities. We previously reported the independence of source memory for self-generated information from executive function, but we did not test its association to attention or verbal memory (21) . With some exceptions (22 , 23) , source memory deficits in schizophrenia have not been examined in relation to general neurocognition.

A number of studies have shown that symptomatic schizophrenia patients manifest poor memory for the source of all item types, not just self-generated information, and that patients with severe psychosis also demonstrate an external response bias, or a tendency to attribute information to an external source (22 – 29) . However, some recent studies have identified source monitoring deficits in patients without acute positive symptoms who do not show the external response bias observed in more symptomatic patients (30 , 31) . Furthermore, source memory performance of siblings has been shown to be intermediate between that of patients and healthy comparison subjects (30) . Taken together, the recent evidence suggests that source monitoring deficits represent a trait marker for schizophrenia above and beyond the external response bias described as state markers in earlier studies.

These two considerations—the specific nature of self-referential source memory performance in clinically stable schizophrenia patients and the potential utility of self-referential source memory performance as a probe into the component processes underlying social cognitive abilities—formed the rationale for this study, with several direct theoretical and clinical implications. Chronic psychosis has long been conceptualized as a disorder of the self and the self’s relationship to the other—aspects of the illness that are most troubling to patients and to society at large, and thus clearly deserving of further study. Additionally, since social cognitive performance is now recognized as a crucial factor mediating functional outcome for patients, it must increasingly become a focus of treatment, which will require a thorough understanding of its significant component processes. Thus, we conducted this study to address the following questions:

1. Do individuals with schizophrenia manifest specific deficits in remembering the source of self-generated information in the presence of intact source memory for external information and intact recognition of new items?

2. Do we find, as would be predicted by the functional imaging literature, that self-referential source memory performance is differentially related to social cognition in healthy subjects and in schizophrenia patients?

3. What role do general cognitive abilities play in the relationship between self-referential source memory performance and social cognition?

Method

Participants

Ninety-one schizophrenia patients were recruited from psychiatric outpatient clinics in the San Francisco Bay area. Thirty healthy comparison subjects were recruited from the community and matched to the schizophrenia group on age, gender ratio, ethnicity, premorbid IQ, and parental education ( Table 1 ). The groups differed significantly in education and current IQ estimate. A diagnosis of schizophrenia was confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (32) , an extended version of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; 3 , 33) , and a medical chart review. Healthy comparison subjects were screened to rule out lifetime history of mental illness and family history of schizophrenia. Exclusion criteria for all subjects included a history of head trauma, substance abuse during the past 6 months, neurological disorders, and English as a second language. All schizophrenia patients were clinically stable at the time of testing. Symptom severity varied broadly, with average PANSS ratings in the mild range ( Table 1 ). Participants provided written informed consent after the study procedures were fully explained and received nominal payment for their participation.

Measures

An information source memory task (21) was used to assess source memory for three types of word item: self-generated, experimenter-presented, and new. The task is conducted in two phases—a study phase and a testing phase. During the study phase, the subject is presented with a list of 40 sentences, each containing a noun and a verb followed by either a target word (underlined) or a fill-in-the-blank space, alternating from one sentence to the next (for example, “The boy threw the ball ”; “The captain sailed the ___”; “The queen ruled the land ”; “The cat chased the ___.”) The subject is asked to read each sentence aloud and, for each blank, to “make up a word and say it aloud.” The experimenter prints the subject’s self-generated target words on a “test list.” The subject thus reads aloud 20 experimenter-generated target words and must self-generate and speak aloud 20 target words. The order of the sentence stimuli is varied among subjects.

For the testing phase, the experimenter presents the test list to the subject approximately 2 hours later. This list contains 40 word pairs from the original sentence stimuli, with target words that were generated by either the experimenter or the subject (e.g., boy – ball , captain – ship , queen – land , cat – mouse ). The test list also contains 20 new word pairs containing words that are highly associated (e.g., bird – nest ). The 60 word pairs on the test list are presented in pseudorandom order. The subject is told that the test list contains word pairs from the sentences that he or she read aloud in part 1 as well as some new word pairs. The subject is asked to determine, for each word pair, whether the target word is “brand-new,” whether it is a word that he or she “made up and said aloud” when reading the original sentence, or whether it is a word that was underlined and that he or she simply “read aloud” (experimenter-presented).

Social cognition measures

Immediate and delayed recognition of emotionally neutral faces was assessed using the Test of Memory and Learning facial memory test (34) . A facial affect recognition test assessed basic emotion identification. Neutral prosody and emotional prosody were measured using subtests from the Florida Affect Battery (see reference 3 for a full description of these measures).

General cognitive factors: attention, verbal memory, executive functioning, and IQ

Age-adjusted z scores from the following measures were used: the WAIS-R freedom from distractibility index; the California Verbal Learning Test immediate recall total (trials 1–5); the composite score of the total number of categories and total number of errors from a modified version of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (35) ; and the WAIS-R full-scale IQ.

Data Analyses

The dispersion of all variables was examined for “restriction of range.” All variables were normally distributed with the exception of false positive errors on the source memory task (right-skewed) and neutral prosody (left-skewed). Data for these measures were analyzed with both parametric and nonparametric procedures, with identical findings. Parametric statistical procedures were used to analyze all other measures. Missing values on one to two measures for four schizophrenia subjects and three healthy comparison subjects were replaced by the sample mean values for those measures. Only slight, nonsignificant changes occurred when these variables were reanalyzed without mean substitution.

A social cognition composite score was calculated for each participant as the average z score across the five social cognition measures (facial affect recognition, facial memory test immediate recognition, facial memory test delayed recognition, neutral prosody, and emotional prosody). The social cognition composite was normally distributed, with acceptable internal-consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.72). Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used to test between-group differences on the three source memory measures (hit rates for self, experimenter, and new) and to test group differences on the five measures of social cognition. Univariate analysis of covariance was used to assess group differences on the social cognition composite score. Age was entered as a covariate in all analyses.

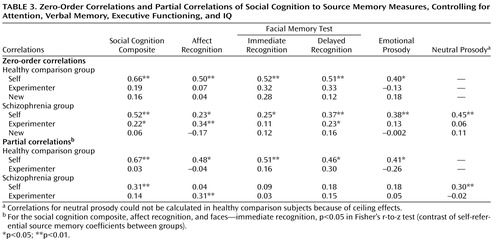

Zero-order correlations assessed the association of social cognition (the composite score and the five individual social cognition measures) to source memory (self-generated, experimenter-presented, and new hit rates). These were followed by partial correlations, controlling for the effects of attention, verbal memory, executive functioning, and IQ. Fisher’s r-to-z transformations allowed for testing of between-group differences in the magnitude of these associations. All tests of significance were two-tailed. A multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine the unique contributions of self-referential source memory, attention (WAIS-R attention index), verbal memory (California Verbal Learning Test immediate recall total, trials 1–5), executive functioning (Wisconsin Card Sorting Test composite score), and IQ to the social cognition composite score.

Results

Between-Group Analyses: Source Memory and Social Cognition Measures

The source memory MANCOVA revealed a significant omnibus F value (F=3.58, df=3, 116, p=0.016), with significantly lower performance on self-referential source memory in schizophrenia patients relative to healthy comparison subjects, while controlling for the effects of age (F=9.89, df=1, 118; p=0.002). The magnitude of this effect was moderate to large (Cohen’s d=0.79). In contrast, the groups did not differ significantly in source memory for externally presented items, recognition memory (correct detection of new items), or false positive error measures.

The social cognition MANCOVA omnibus F value was also significant (F=10.41, df=5, 114, p<0.001). Schizophrenia patients performed significantly lower in the following measures of social cognition ( Table 2 ): facial memory immediate recognition (F=42.52, df=1, 118, p<0.001), facial memory delayed recognition (F=12.40, df=1, 118, p<0.001), emotional prosody (F=14.71, df=1, 118, p<0.001), and neutral prosody (F=4.53, df=1, 118, p<0.035). The groups did not differ significantly in facial affect recognition. Schizophrenia patients also performed significantly lower on the social cognition composite score (F=21.32, df=1, 118, p<0.001).

Within-Group Contrasts: The Self-Generation Effect in Memory

The self-generation effect (enhanced memory for self-generated information, such as words, pictures, objects, etc. [36] ) was evident in healthy comparison subjects: in this group, source memory for self-generated items was significantly greater than source memory for externally presented items (F=93.70, df=1, 29, p<0.001) and recognition memory (correct detection of new items) (F=12.06, df=1, 29, p=0.002). In the schizophrenia patients, source memory for self-generated items was also significantly greater than source memory for externally presented items (F=62.61, df=1, 29, p<0.001), but it did not differ significantly from recognition memory.

Associations of Social Cognition to Self-Referential Source Memory Versus Source Memory for Externally Presented Items

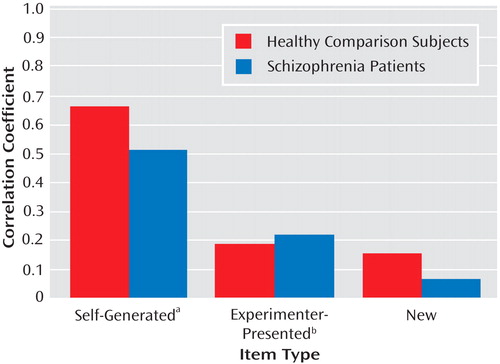

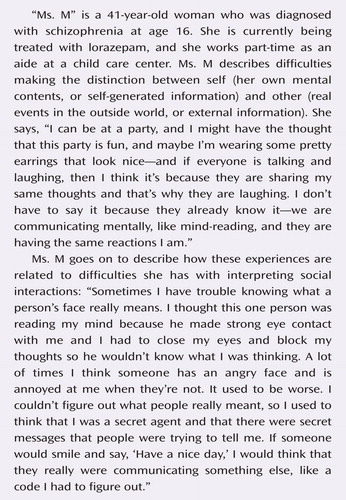

All zero-order correlations of social cognition measures to self-referential source memory were significant in both healthy comparison subjects and schizophrenia patients ( Table 3 ). In contrast, all correlations of social cognition measures to source memory for externally presented items were not significant in healthy comparison subjects, while in the schizophrenia sample, two of the five social cognition measures showed small but significant correlations to source memory for externally presented items ( Table 3 ). Correlations of all social cognition measures and recognition memory (correct detection of new items) were not significant in either group. Figure 1 illustrates the associations of the social cognition composite score to source memory measures in both subject groups. None of the variable distributions showed evidence of restriction of range in either subject group, despite the greater variance observed on performance measures in the schizophrenia group.

a For self-generated items, the coefficient was statistically significant (p<0.001) for both groups.

b For the experimenter-presented items, the coefficient was statistically significant (p=0.036) for the schizophrenia group.

The partial correlations ( Table 3 ) revealed that the social cognition composite score and individual measures of social cognition were significantly correlated with self-referential source memory in the healthy comparison group, independent of the effects of attention, verbal memory, executive functioning, and IQ. In contrast, in the schizophrenia group, associations between social cognition measures and self-referential source memory were significantly attenuated when the effects of attention, verbal memory, executive functioning, and IQ were removed.

Fisher’s r-to-z transformations revealed that the association between measures of social cognition and self-referential source memory were significantly greater in healthy subjects compared with schizophrenia patients for the following variables: social cognition composite, affect recognition, and facial memory test immediate recognition. Partial correlations of social cognition measures to source memory for externally presented items were nonsignificant in both groups, with the exception of facial affect recognition in the schizophrenia group.

The Relationship of Self-Referential Source Memory, Social Cognition, and General Cognitive Abilities

In the healthy comparison group, the social cognition composite score was not significantly correlated with measures of general cognition (attention, verbal memory, executive functioning, or IQ). In contrast, in the schizophrenia group, the social cognition composite score showed significant correlations (all p values <0.001, two-tailed) with attention (r=0.57), verbal memory (r=0.41), executive functioning (r=0.46), and IQ (r=0.51). The multiple regression analysis ( Table 4 ) revealed distinct models accounting for approximately the same amount of variance in social cognition in the healthy comparison group (56%) and schizophrenia group (50%). In the comparison group, self-referential source memory was the sole significant predictor of social cognition in the model, with a contribution of verbal memory that approached significance. In contrast, in the schizophrenia group, self-referential source memory, attention, and executive functioning contributed approximately equally to the variance in social cognition, while the effects of verbal memory and IQ were nonsignificant.

Discussion

Self-Referential Source Memory in Schizophrenia Represents a Unique Cognitive Deficit

Using a large sample of stable schizophrenia outpatients, we found that participants showed deficits in self-referential source memory in the presence of intact external source memory and intact recognition memory, with no external response bias. In other words, compared with healthy subjects, individuals with schizophrenia had a specific difficulty in recognizing that they themselves were the source of words generated during an earlier sentence completion task. Overall, our results are consistent with the notion that processing information with respect to the “self” makes use of cognitive operations that are in part distinct from those underlying general memory abilities for external information, and that individuals with schizophrenia have difficulty recruiting these specific operations. The effect size of this self-referential source memory impairment in the schizophrenia sample was medium to large (Cohen’s d=0.79).

Earlier studies have tended to show poor memory for the source of all item types in symptomatic inpatient schizophrenia subgroups relative to healthy comparison subjects, as well as an external response bias (22 – 29) . Recent data from clinically remitted schizophrenia patients indicate that impaired source monitoring is a trait marker of the illness, rather than a state-dependent feature (30) , and that internal source monitoring deficits are evident without response bias (31) . Our finding of a dissociation between self-referential and external source memory, in the absence of response bias, may reflect our sample of clinically stable outpatients and/or the sensitivity of our measure (measures of source memory vary extensively across studies). Interestingly, one previous study detected a dissociation of self-referential versus external source memory in both mildly and severely ill schizophrenia patients compared with healthy subjects with the aid of multinomial modeling techniques (23) . The sum of the evidence thus suggests that impaired self-referential source memory represents a unique cognitive impairment in schizophrenia.

The Association Between Self-Referential Source Memory and Social Cognition Seen in Healthy Subjects Is Attenuated in Schizophrenia

In both the schizophrenia patients and the healthy subjects, self-referential source memory showed unique associations with social cognition, compared with memory for externally presented information or simple recognition memory. In other words, the ability to remember that “self was source” on a sentence completion task was strongly related to basic social cognitive processes of face recognition and emotion identification. In contrast, general memory for “external” target words from the sentences and recognition of new items were not related to these social cognition abilities in either group. Our data indicate that this strong relationship was not mediated by the emotional valence of the stimuli, because our emotionally neutral self-referential source memory task showed significant associations to both emotionally laden and emotionally neutral measures of basic social cognition.

Simulation theory (37) and perception-action-based theories propose that one’s internal representations of actions and feelings (“self”) are activated when perceiving such states in the “other” (38 , 39) . At the behavioral level, for example, subjects demonstrate unconscious mimicry of the facial expressions they observe in others (e.g., reference 40 ). At the neural level, facial and prosodic emotion perception activate brain regions also implicated during the active experience of emotion (e.g., reference 41 ). As Brunet-Gouet and Decety (11) hypothesize, the inability to track the sense of “self” or agency may lead to a profound impairment in the processing of emotional and social information. Our behavioral data indicate that such a sense of self-agency is indeed strongly associated with social and emotional information processing in healthy subjects and that deficits in this operation are associated with impaired processing of social and emotional information in schizophrenia subjects.

In the healthy comparison group, the associations between self-referential source memory and social cognition remained unchanged while controlling for the effects of attention, verbal memory, executive functioning, and IQ. This highlights the distinct nature of the relationship between self-referential and social cognition and its relative “dissociation” from other general cognitive abilities, consistent with the distinct neural correlates for these processes observed in neuroimaging studies of healthy subjects (6 , 16) . However, in stark contrast to the healthy comparison group, when the effects of attention, verbal memory, executive functioning, and IQ were controlled in the schizophrenia group, the magnitude of the associations between self-referential source memory and social cognition measures was reduced and significantly different from the healthy comparison subjects.

Taken together, these data indicate that although social and self-referential cognition are uniquely associated in both subject groups, this relationship is attenuated in schizophrenia patients and is mediated by general cognitive abilities, as further indicated by the multiple regression analysis. In the healthy subjects, approximately 45% of the variance in social cognition was accounted for by the independent contribution of self-referential source memory, while the contributions of the general cognitive factors were nonsignificant. In marked counterpoint, in the schizophrenia patients, the variance in social cognition was accounted for by the independent contributions of self-referential source memory (9%), attention (9%), and executive functions (8%).

The Disturbed Processing of “Self” and “Other” in Schizophrenia Has Neurocognitive Underpinnings

In sum, we find that individuals with schizophrenia are impaired in their ability to recognize that their “self” was the source of an earlier mental event. In healthy subjects, this specific ability to recognize “self as source” is strongly and uniquely related to their ability to identify facial and vocal emotion and to recognize faces, likely because we normally process social stimuli (the “other”) in part by activating internal representations of our own sense of “self.” Subjects with schizophrenia, however, are impaired in this process—because of, we suggest, disturbances in the neurocognitive systems that normally facilitate the accurate processing of both self-referential and social information (11 , 19 , 42) . They thus must rely on the contributions of other general cognitive operations, such as attention and executive functions, in order to accomplish social cognitive tasks.

Such a cognitive “solution” is likely to be less efficient, less accurate, and less reliable, leading to distortions in the representation of both self-referential and social (interpersonal) information. In the former case, this might contribute to the impaired sense of agency, decreased insight, and deficits in self-monitoring that are known to characterize schizophrenia (11 , 43) . In the latter instance, these could play a role in difficulties with empathy (39) , mentalization (making attributional judgments about the mental states of others [11] ), and emotional and social perception (perception and interpretation of intimacy, status, mood state, veracity, and so on [2] ). The ongoing clinical effects of such distortions are thus potentially quite profound and suggest that the neurocognitive associations we present here provide a parsimonious explanation for the observed disturbances seen in the sense of “self” and “other” in schizophrenia. A greater understanding of these associations will lead to the development of more informed treatment approaches and ultimately to improved quality of life for individuals with the illness.

1. Arieti S: Interpretation of Schizophrenia. New York, Basic Books, 1974Google Scholar

2. Green MF, Olivier B, Crawley JN, Penn DL, Silverstein S: Social cognition in schizophrenia: recommendations from the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia New Approaches Conference. Schizophr Bull 2005; 31:882–887Google Scholar

3. Poole JH, Tobias FC, Vinogradov S: The functional relevance of affect recognition errors in schizophrenia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2000; 6:649–658Google Scholar

4. Bryson G, Bell M, Lysaker P: Affect recognition in schizophrenia: a function of global impairment or a specific cognitive deficit. Psychiatry Res 1997; 71:105–113Google Scholar

5. Brune M: Emotion recognition, “theory of mind,” and social behavior in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2005; 133:135–147Google Scholar

6. Gilbert S, Spengler S, Simons JS, Frith CD, Burgess PW: Differential functions of lateral and medial rostral prefrontal cortex (area 10) revealed by brain-behavior associations. Cereb Cortex 2006; 16:1783–1789Google Scholar

7. Ochsner KN, Knierim K, Ludlow DH, Hanelin J, Ramachandran T, Glover G, Mackey SC: Reflecting upon feelings: an fMRI study of neural systems supporting the attribution of emotion to self and other. J Cogn Neurosci 2004; 16:1746–1772Google Scholar

8. Mitchell JP, Macrae CN, Banaji MR: Encoding-specific effects of social cognition on the neural correlates of subsequent memory. J Neurosci 2004; 24:4912–4917Google Scholar

9. Harvey PO, Fossati P, Lepage M: Modulation of memory formation by stimulus content: specific role of the medial prefrontal cortex in the successful encoding of social pictures. J Cogn Neurosci 2007; 19:351–362Google Scholar

10. Iacoboni M, Lieberman MD, Knowlton BJ, Molnar-Szakacs I, Moritz M, Throop CJ, Fiske AP: Watching social interactions produces dorsomedial prefrontal and medial parietal bold fMRI signal increases compared to a resting baseline. Neuroimage 2004; 21:1167–1173Google Scholar

11. Brunet-Gouet E, Decety J: Social brain dysfunctions in schizophrenia: a review of neuroimaging studies. Psychiatry Res 2006; 148:75–92Google Scholar

12. Vinogradov S, Luks TL, Simpson GV, Schulman BJ, Glenn S, Wong AE: Brain activation patterns during memory of cognitive agency. Neuroimage 2006; 31:896–905Google Scholar

13. Simons JS, Davis SW, Gilbert SJ, Frith CD, Burgess PW: Discriminating imagined from perceived information engages brain areas implicated in schizophrenia. Neuroimage 2006; 32:696–703Google Scholar

14. Ochsner KN, Beer JS, Robertson ER, Cooper JC, Gabrieli JD, Kihsltrom JF, D’Esposito M: The neural correlates of direct and reflected self-knowledge. Neuroimage 2005; 28:797–814Google Scholar

15. Macrae CN, Moran JM, Heatherton TF, Banfield JF, Kelley WM: Medial prefrontal activity predicts memory for self. Cereb Cortex 2004; 14:647–654Google Scholar

16. Gusnard DA, Akbudak E, Shulman GL, Raichle ME: Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: relation to a default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98:4259–4264Google Scholar

17. Beck A, Rector A: Cognitive approaches to schizophrenia: theory and therapy. Ann Rev Clin Psychol 2005; 1:577–606Google Scholar

18. Ogden T: The Primitive Edge of Experience. Northvale, NJ, Jason Aronson, 1989Google Scholar

19. Vinogradov S, Luks TL, Schulman BJ, Simpson GV: Deficit in a neural correlate of reality monitoring in schizophrenia patients. Cereb Cortex (Epub ahead of print, May 23, 2008)Google Scholar

20. Johnson MK: Memory and reality. Am Psychol 2006; 61:760–771Google Scholar

21. Vinogradov S, Willis-Shore J, Poole JH, Marten E, Ober BA, Shenaut GK: Clinical and neurocognitive aspects of source monitoring errors in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1530–1537Google Scholar

22. Seal ML, Crowe SF, Cheung P: Deficits in source monitoring in subjects with auditory hallucinations may be due to differences in verbal intelligence and verbal memory. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 1997; 2:273–290Google Scholar

23. Keefe RS, Arnold MC, Bayen UJ, McEvoy JP, Wilson WH: Source-monitoring deficits for self-generated stimuli in schizophrenia: multinomial modeling of data from three sources. Schizophr Res 2002; 57:51–67Google Scholar

24. Bentall RP, Baker GA, Havers S: Reality monitoring and psychotic hallucinations. Br J Clin Psychol 1991; 30:213–222Google Scholar

25. McGuire PK, Silbersweig DA, Wright I, Murray RM, Frackowiak RS, Frith CD: The neural correlates of inner speech and auditory verbal imagery in schizophrenia: relationship to auditory verbal hallucinations. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:148–159Google Scholar

26. Morrison AP, Haddock G: Cognitive factors in source monitoring and auditory hallucinations. Psychol Med 1997; 27:669–679Google Scholar

27. Allen PP, Johns LC, Fu CH, Broome MR, Vythelingum GN, McGuire PK: Misattribution of external speech in patients with hallucinations and delusions. Schizophr Res 2004; 69:277–287Google Scholar

28. Johns LC, Gregg L, Allen P, McGuire PK: Impaired verbal self-monitoring in psychosis: effects of state, trait, and diagnosis. Psychol Med 2006; 36:465–474Google Scholar

29. Anselmetti S, Cavallaro R, Bechi M, Angelone SM, Ermoli E, Cocchi F, Smeraldi E: Psychopathological and neuropsychological correlates of source monitoring impairment in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2007; 150:51–59Google Scholar

30. Brunelin J, d’Amato T, Brun P, Bediou B, Kallel L, Senn M, Poulet E, Saoud M: Impaired verbal source monitoring in schizophrenia: an intermediate trait vulnerability marker? Schizophr Res 2007; 89:287–292Google Scholar

31. Henquet C, Krabbendam L, Dautzenberg J, Jolles J, Merckelbach H: Confusing thoughts and speech: source monitoring and psychosis. Psychiatry Res 2005; 133:57–63Google Scholar

32. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

33. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261–276Google Scholar

34. Reynolds C, Bigler ED: Test of Memory and Learning Examiner’s Manual. Austin, Tex, Pro-Ed, 1994Google Scholar

35. Nelson H: A modified card sorting test sensitive to frontal lobe defects. Cortex 1976; 12:313–324Google Scholar

36. Mulligan N, Lozito JP: Self-generation and memory, in The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory, vol 45. Edited by Urbana RB. San Diego, Academic Press, 2004, pp 175–210Google Scholar

37. Davies M, Stone T: Mental Simulation: Evaluations and Applications. Oxford, England, Blackwell Scientific Publishers, 1995Google Scholar

38. Preston SD, de Waal FB: Empathy: its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav Brain Sci 2002; 25:1–20Google Scholar

39. Decety J, Jackson PL: A social-neuroscience perspective on empathy. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2006; 15:54–58Google Scholar

40. Dimberg U, Thunberg M, Elmehed K: Unconscious facial reactions to emotional facial expressions. Psychol Sci 2000; 11:86–89Google Scholar

41. Adolphs R, Damasio H, Tranel D, Cooper G, Damasio AR: A role for somatosensory cortices in the visual recognition of emotion as revealed by three-dimensional lesion mapping. J Neurosci 2000; 20:2683–2690Google Scholar

42. Garrity AG, Pearlson GD, McKiernan K, Lloyd D, Kiehl KA, Calhoun VD: Aberrant “default mode” functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:450–457Google Scholar

43. Shad MU, Tamminga CA, Cullum M, Haas GL, Keshavan MS: Insight and frontal cortical function in schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Res 2006; 86:54–70Google Scholar