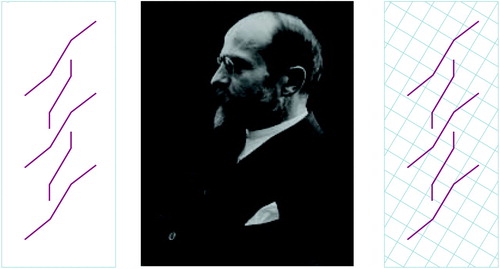

Theodor Lipps and the Concept of Empathy: 1851–1914

Theodor Lipps was born in 1851 in Wallhalben/Palatinate, Germany, and died in 1914 in Munich. He was given a chair in philosophy in 1884 in Bonn, where he wrote a comprehensive account of psychology, Fundamentals of Psychic Life(1) . Sigmund Freud was a knowledgeable admirer of Lipps (2) . Lipps also advocated a psychic energy that can alter thought and behavior if inhibited in its natural course (“law of psychic congestion”). In 1898 Freud admitted in his letters to Fliess, “I found the substance of my insights stated quite clearly in Lipps, perhaps rather more so than I would like” (3) . In Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, Freud acknowledged Lipps’s Comicality and Humor(4) as the “book...that has given me the courage to undertake this attempt as well as the possibility of doing so” ( 5 ; translation from reference 2).

Today Theodor Lipps is remembered as the father of the first scientific theory of Einfühlung (“feeling into,” “empathy”), although the term had earlier been coined by Robert Vischer in 1873. Unlike his predecessors, he used the notion of Einfühlung to explain not only how people experience inanimate objects, but also how they understand the mental states of other people. From translating Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature into German, Lipps had learned the concept of “sympathy” as a process that allows the contents of “the minds of men” to become “mirrors to one another” (6) .

Lipps developed his theory of Einfühlung to explain optical illusions (7) . Lipps intended to develop a comprehensive “esthetic-mechanical” theory explaining all kinds of geometrical illusions. He followed the view of Helmholtz, who regarded them as errors of judgment and not as errors of perception. Judgment is formed on the basis of former personal experience by unconscious analogy and inference. Lipps believed that our experience may cause us to see an activity of “force” and “tendency” (counterforce) in geometrical forms by projecting “living” activity into objects. The illusion of two intersecting waves appears in the figure above from his work (8) , even though the middle segments are actually parallel and aligned with each other, as shown by the grid.

Einfühlung, according to Lipps, entails fusion between the observer and his or her object. For Lipps, the unconscious process of Einfühlung is based on a “natural instinct” and on “inner imitation.” He used the example of watching an acrobat on a tightrope and suggested that perceived movements and affective expressions are “instinctively” and simultaneously mirrored by kinesthetic “strivings” and experience of corresponding feelings in the observer.

Lipps’s introspectionist approach was ultimately eclipsed by experimental psychology and early behaviorism (9) , which became far more influential during the first half of the 20th century (10) . Nevertheless, Lipps’s thinking inspired such philosophers as Husserl, Dilthey, Weber, and Edith Stein. In 1909 Edward Titchener translated Einfühlung as “empathy” (11) . Although considered speculative in his time, Lipps’s theory of “inner imitation” (12) may find some reflection in present-day concepts of emotional contagion and perception-action models of empathy (13) .

1. Lipps T: Grundtatsachen des Seelenlebens. Bonn, Germany, Cohen, 1883Google Scholar

2. Pigman GW: Freud and the history of empathy. Int J Psychoanal 1995; 76:237–256Google Scholar

3. Freud S: The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess 1887–1904. Translated and edited by Masson JM. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1986, p 325Google Scholar

4. Lipps T: Komik und Humor: Eine psychologisch-ästhetische Untersuchung. Hamburg, Germany, L Voss, 1898Google Scholar

5. Freud S: Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewussten, in Gesammelten Werken, band VI (1905). Frankfurt, S Fischer, 1958, p 7Google Scholar

6. Hume D: A Treatise of Human Nature, 2nd ed. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1978, p 365Google Scholar

7. Lipps T: Raumästhetik und geometrisch-optische Täuschungen. Leipzig, JA Barth, 1897Google Scholar

8. Lipps T: Optische Streitfragen. Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Physiologie der Sinnesorgane 1892; 3:493–504Google Scholar

9. Watson JB: Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychol Rev 1913; 20:158–177Google Scholar

10. Davison GC, Neale JM, Hautzinger M: Klinische Psychologie. Weinheim, Germany, Beltz PVU, 2007Google Scholar

11. Titchener EB: Lectures on the Experimental Psychology of Thought Processes. New York, Macmillan, 1909Google Scholar

12. Lipps T: Ästhetik: Psychologie des Schönen und der Kunst: Grundlegung der Ästhetik, Erster Teil. Hamburg, Germany, L Voss, 1903Google Scholar

13. Preston SD, DeWaal FBM: Empathy: its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav Brain Sci 2002; 25:1–72Google Scholar