Cingulate Gyrus Tumor Presenting as Panic Attacks

To The Editor: The diagnosis of panic disorder is usually straightforward, but tumors or epilepsy of the temporal lobe may rarely present as panic attacks (1) . We report the case of a teenager who presented with short-lasting episodes resembling panic attacks secondary to a dorsal anterior cingulate ganglioglioma.

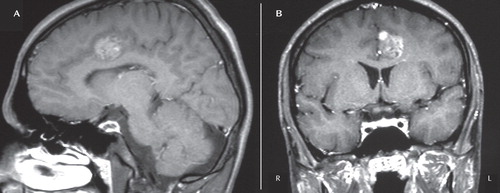

A 15-year-old boy presented with a 3-month history of recurrent, unexpected panic attacks occurring four to five times daily. His clinical history was unremarkable, and no stressful events were reported. During his panic attacks, he experienced intense anxiety, palpitations, trembling, shortness of breath, feelings of choking, dizziness, lightheadedness, and hot flashes. The episodes were unprovoked and usually lasted 1 to 2 minutes. On two occasions, he reported loss of muscle tone in the lower limbs. He developed concern (after >1 month) about having further attacks and their implications. No drug abuse, medication intake, criteria for other anxiety disorders, or agoraphobia was present. A diagnosis of panic disorder was presumed, and the patient was treated with bromazepam without benefit. Neurological consultation was then requested. General neurological examination was normal. Blood and urine tests, including thyroid hormones, were unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a tumor on the left dorsal anterior cingulate ( Figure 1 ). An electroencephalogram (EEG) showed epileptiform frontal discharges (left >right) during a panic attack. The patient started carbamazepine with complete disappearance of panic attacks. He underwent neurosurgical radical resection of grade II ganglioglioma that did not invade the corpus callosum or surrounding structures. After resection, carbamazepine was discontinued without reappearance of panic attacks.

a Sagittal (A) and coronal (B) gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted sections of the left dorsal anterior cingulate tumor (Talairach coordinate: –12.5, 9.6, 44.1; Montreal Neurological Institute: –12.6, 8.3, 4.8). R=right side; L=left side.

This case underscores the importance of ruling out general medical conditions for panic disorder diagnosis. The differential diagnosis between panic disorder and partial epileptic seizures on the basis of symptoms is sometimes challenging (1) . In light of this case report, it would be prudent for patients with similar short duration (<2 minutes) of the episodes or loss of muscle tone to have an EEG and MRI before a diagnosis of panic disorder is determined. Partial temporal lobe epilepsy and panic disorder have overlapping symptoms; however, this is the first report of left frontal seizures from a left dorsal anterior cingulate brain ganglioglioma (<0.1% among brain tumors) that presented as panic disorder. The EEG findings and the good response to carbamazepine and tumor removal further support the hypothesis of partial seizures (1) .

The most prevailing neuroanatomical model suggests that panic disorder patients may have an especially sensitive limbic “fear network” involving the amygdala and related brain areas, including the cingulate (2 , 3) . This model is consistent with converging experimental evidence that indicates a role of the left dorsal anterior cingulate in the pathogenesis of panic disorder (4) .

1. Thompson SA, Duncan JS, Smith SJ: Partial seizures presenting as panic attacks. BMJ 2000; 321:1002–1003Google Scholar

2. Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD: Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revised. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:493–505Google Scholar

3. Malizia AL: What do brain imaging studies tell us about anxiety disorders? J Psychopharmacol 1999; 13:372–378Google Scholar

4. Sakai Y, Kumano H, Nishikawa M, Sakano Y, Kaiya H, Imabayashi E, Ohnishi T, Matsuda H, Yasuda A, Sato A, Diksic M, Kuboki T: Changes in cerebral glucose utilization in patients with panic disorder treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy. Neuroimage 2006; 33:218–226Google Scholar