Predictors of Attrition During Initial (Citalopram) Treatment for Depression: A STAR*D Report

Abstract

Objective: Premature attrition from treatment may lead to worse outcomes and compromise the integrity of clinical trials in major depressive disorder. The purpose of this study was to identify the pretreatment predictors of attrition during acute treatment with citalopram in a large, “real world” clinical trial. Method: A total of 4,041 adult outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder were enrolled in treatment with citalopram for up to 14 weeks. Attrition was defined as “immediate” (patients who attended a baseline visit only) or “later” (patients who attended at least one postbaseline visit but who dropped out before the 12-week visit). Results: Overall, 26% of enrolled patients dropped out of the acute phase treatment for nonmedical reasons. Of these, 34% dropped out immediately, 59% dropped out by week 12, and 7% dropped out after 12 weeks. Immediate attrition was associated with younger age, less education, and higher perceived mental health functioning. Attrition later in treatment was associated with younger age, less education, and African American race. Experience with more than one episode of depression was associated with less attrition. Conclusions: In clinical trials and clinical practice, several time points in treatment may provide opportunities to engage and encourage populations at higher risk for attrition and populations with high-risk presentation of illness. Additionally, more aggressive forms of treatment implemented earlier in the treatment process in order to increase the likelihood of more rapid efficacy may reduce dropout rates.

Major depressive disorder is a common, debilitating disorder, which cost the United States $83.1 billion in 2000 (1) . Most patients with major depressive disorder have high rates of morbidity and mortality (2) , and the disorder is typically associated with a chronic or recurrent course (3 , 4) . Remission, the virtual absence of symptoms, is the goal of acute treatment, since it is associated with improved functioning (5) and a better prognosis (6) than response without remission. However, in order for treatment to be most effective, it must be delivered at a fully adequate dose and for an adequate duration. Approximately two-thirds of depressed patients do not remit with their initial treatment (4 , 7) and require one or more additional treatment steps to achieve remission.

When patients discontinue acute treatment prematurely, which is called attrition, it has a negative impact on treatment outcomes and clinical trials. Without adequate treatment, the outcomes for major depressive disorder are worse (8) . In clinical trials, attrition is often associated with nonrandom, missing data that compromise the interpretation of results or require inordinately large sizes of the study groups. However, few studies have addressed attrition specifically. Several studies have evaluated treatment adherence, which is the extent to which a patient’s behavior corresponds with the treatment recommendations of a health care provider (9) . Studies of adherence are often difficult to interpret, since they involve the use of proxy measures, such as pharmacy databases, medical records, self- or physician reports, or other methods, that do not represent an outcome as clear as attrition.

Attrition rates during the first 10 weeks of outpatient treatment for major depressive disorder have ranged from 20%–40% in randomized clinical trials in which close patient supervision was provided and have reached as high as 60% in naturalistic settings (10) . A few studies have examined the sociodemographic or clinical pretreatment predictors of attrition during the acute phase of treatment in clinical trials with study group sizes ranging from 66 to 224 subjects (11 – 14) . In these studies, the following characteristics predicted attrition: younger age (11 , 14) , racial or ethnic minority status (14) , male gender (11) , unemployment, fewer years of education, poorer social adjustment, lower income (12) , greater depressive symptom severity, and greater anxiety (13 , 14) . However, these studies were efficacy trials in research settings with symptomatic volunteers, and thus findings may not generalize to patients in “real world” clinical practice settings. Rates of attrition associated with treatment-related events have been reported in two meta-analyses of clinical trials involving 1,610 and 1,791 patients (15 , 16) . The range of attrition related to adverse events was reported as 3.7%–14.2%, and the range of attrition because of a lack of efficacy was reported as 2.1%–10.6%.

Identifying pretreatment predictors of attrition would enable clinicians and researchers to target prevention efforts to patients who are at greater risk of attrition. Additionally, exploration of the impact of side effects and the lack of efficacy during the acute phase of treatment could enable clinicians and researchers to focus their efforts toward reducing attrition.

The purpose of the present study was to identify the pretreatment predictors of treatment attrition in patients with major depressive disorder using a large cohort of self-declared patients in representative primary and psychiatric practice settings from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study (www.star-d.org) (17 , 18) . These data allowed us to examine the occurrence and timing of attrition in the acute phase of treatment of a clinical trial. In our study, we address the following questions:

1. How common was attrition and when did it occur?

2. Did any baseline clinical or sociodemographic characteristic distinguish the attrition group from the nonattrition group?

3. Did any baseline characteristic distinguish the immediate attrition group (those patients who attended a baseline visit only) and the later attrition group (those patients who exited following at least one postbaseline measure) from those who did not exit?

4. Did any baseline characteristic independently distinguish attrition, immediate attrition, or later attrition subjects from those subjects who were not in their group?

Additionally, we explore the treatment-related factors associated with attrition.

Method

The STAR*D rationale, design, and description of treatment settings are described elsewhere (17 , 18) .

Participants

Participants were STAR*D enrolled outpatients, ages 18 to 75, who were diagnosed with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder. Participants were recruited from 18 primary and 23 psychiatric care clinical sites across the United States that serve the public and private sectors. A pretreatment score ≥14 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (19) was required for study entry.

Broad inclusion and minimal exclusion criteria were used to ensure a comprehensive representative cohort of “real world” patients to maximize the generalizability of findings. The enrollment of symptomatic volunteers and advertising for subjects were not permitted. Providing that their clinicians considered outpatient care appropriate, patients with most psychiatric and medical comorbidities could be enrolled as well as patients who were suicidal or abusing substances. Patients with a clear history of intolerance to the medications used in the first two levels of treatment were excluded as well as patients with a lifetime history of bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, current anorexia nervosa, or a current primary diagnosis of bulimia or obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Patients were excluded if they were receiving antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, mood stabilizers, CNS stimulants, or nonstudy antidepressant medications or if they were breastfeeding or pregnant.

The study was approved and overseen by the institutional review boards of the STAR*D National Coordinating Center, Data Coordinating Center, and 14 regional centers and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Data Safety and Monitoring Board. A complete description of the study, including all risks, benefits, and adverse events, was provided to the participants, who gave written informed consent prior to the study entry.

Treatment

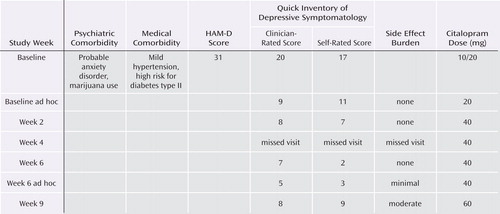

In our analyses, we focused on the first STAR*D treatment step using the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram (Level 1). The protocol recommended treatment sessions at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12. The visit schedule was flexible, allowing a window of ±6 days from the protocol date for each visit. The recommended starting dose of citalopram was 20 mg/day, which was to be increased to 40 mg/day by week 4 and 60 mg/day by week 6. If the participant had a good response (a substantial improvement in symptoms but not remission) at week 12, then treatment could be extended for 2 additional weeks based on clinician judgment.

Using a flexible dosing schedule, measurement-based care (7) guided the treatment, with the timing of dose changes based on the ratings of symptoms and side effects acquired at each treatment visit using the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician-Rated (20 , 21) and the Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating (22) . This approach was designed to provide high quality care and to maximize efficacy but minimize the need for attrition from the protocol.

A web-based treatment monitoring system used by clinicians and clinical research coordinators, with flags that signaled dosing outside the protocol (23) , helped to ensure that participants received a fully adequate dose and duration of citalopram as long as the treatment was tolerated.

Participants who achieved remission (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician-Rated ≤5) with citalopram moved to a 12-month naturalistic follow-up period. Those with a score of 6 to 8 on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician-Rated could move to the follow-up, but were encouraged to move on to the next treatment level. Those with a score ≥9 could proceed directly to the next treatment level. Participants could move to the next treatment level as early as week 4 if they experienced intolerable side effects, if the dose they received could not be increased to the optimal dose because of side effects, by patient preference, or if substantial symptoms at a maximally tolerated dose (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician Rated ≥9) persisted after 9 weeks.

Trained and certified clinical research coordinators at the clinical sites assisted with the protocol implementation, collected various ratings, and provided education and assistance to patients and clinicians.

Measures and Data Collected

At the baseline visit, the clinical research coordinator obtained sociodemographic information, self-reported psychiatric history, measures of depression symptom severity (HAM-D, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician Rated, and Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self-Rated), and information on current general medical illnesses using the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (24) . The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale scoring includes the number of organ systems affected and total burden, a multiple of the number of organ systems affected and the severity of each. Participants completed the self-rated Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (25) , which rated the presence of other axis I psychiatric disorders using a 90% specificity and responded to several questions that addressed their expectations for improvement in making important decisions and being able to enjoy activities of interest. Within 72 hours of the baseline visit, the research-outcomes assessors collected data from the HAM-D (primary STAR*D outcome measure) and the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician Rated (20 , 21) . The presence of atypical (26) or melancholic features (27) was determined using the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinician Rated, while anxious features (28) were based on the HAM-D (19) .

Also within 72 hours of the baseline visit, an interactive voice response system collected depressive symptom severity data using the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self-Rated (20 , 21) , perceptions of mental and physical functioning using the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (29) , and ratings of satisfaction and enjoyment in the domains of daily functioning using the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (30) and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (31) .

Definitions of Attrition

Twelve weeks of treatment were expected for participants who did not move to the follow-up or to Level 2 earlier. Therefore, attrition subjects were defined as those who exited from the study after at least a baseline visit and before the 12-week visit. Those with a medical reason for study termination, such as developing a general medical condition that contraindicated the protocol treatment, were not considered attrition subjects. Since a 14-week visit was at the clinicians’ discretion, subjects who dropped out after the 12-week visit were also not considered to be part of an attrition group. Therefore, subjects in the nonattrition group were defined as those who discontinued citalopram treatment at any time in order to move to the follow-up or to the next treatment level, those who left for medical reasons, and those who left after completing 12 weeks of treatment.

Subjects in the immediate attrition group were those who attended a baseline visit only. Subjects in the later attrition group were those who attended at least one postbaseline visit but who dropped out before the 12-week visit. Because of the ±6-day window for each visit, late attrition subjects were those who exited on or before day 77, since the 12-week visit could have occurred on day 78.

Data Analyses

The baseline characteristics assessed included sociodemographic factors (setting, race, Hispanic ethnicity, gender, marital status, employment and insurance status, age, and years of education) and clinical factors (family history of depression; alcohol or drug abuse; prior suicide attempt[s]; present suicide risk; anxious, melancholic, or atypical features; presence of chronic or recurrent depression; age of onset of first major depressive episode; number of episodes; length of current episode; and time since onset of first episode); the presence and number of psychiatric comorbidities (generalized anxiety disorder, OCD, panic disorder, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], agoraphobia, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, somatoform, hypochondriasis, and bulimia); the number and burden of general medical comorbidities; symptom severity; function and quality of life; and responses to questions pertaining to expectations for improvement.

Summary statistics are presented as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and as percentages for discrete variables. Bivariate logistic regression models were used to identify factors that were associated with each type of attrition. Exploratory stepwise logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify factors independently associated with attrition. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, and thus results must be interpreted accordingly.

Since a large number of comparisons were made in this exploratory report, we used strict criteria to define statistical significance (p<0.001). To keep our presentation brief, we focused primarily on those findings that were statistically significant in both the unadjusted bivariate and the stepwise logistic regressions.

Results

Participants who enrolled in citalopram treatment were representative of the U.S. Census: Caucasian, 76% (N=3,055); African American, 18% (N=709); Asian, 2% (N=70); and other or multiracial, 4% (N=207). Of these, 13% (N=507) were Hispanic.

Figure 1 shows the disposition of the 4,041 participants enrolled in Level 1 by attrition status.

a Immediate attrition: patients who dropped out after a baseline visit only. Later attrition: patients who attended at least one postbaseline visit but exited before week 12. After 12-week cutoff attrition: patients who attended their 12-week visit (day 78–90), but did not attend the scheduled visits after week 12. Among the later attrition group (N=610), 361 (59.2%) exited before the 6-week visit, and 249 (40.8%) exited after the 6-week visit.

Only a few features were significant predictors of attrition in both methods of analysis using the threshold of p<0.001. All significant findings in the stepwise regression ( Table 1 ) were also significant in the unadjusted bivariate analyses (see the table in the data supplement that accompanies the online version of this article). For all attrition subjects, especially among those in the later attrition group, African American race was associated with dropout. Experience with more than one episode of depression was associated with less attrition. For all attrition subjects (patients in both the immediate and later attrition groups), younger age and fewer years of education were associated with attrition. In the immediate attrition group, higher perceived mental health functioning was slightly associated with attrition.

Although they did not meet a priori conservative criterion of significance in both the stepwise and unadjusted bivariate analyses, additional predictors with p<0.001 in the logistic regression and a difference of at least seven percentage points between groups also represented clinically meaningful findings (see the table in the data supplement that accompanies the online version of this article).

Using these criteria, those patients with public insurance dropped out more frequently than those with private insurance, and Hispanic patients dropped out more often later in treatment. Much higher attrition rates were associated with greater numbers of current psychiatric axis I comorbidities, especially three or more. Specific comorbidities, including alcohol or drug abuse, panic disorder, agoraphobia, hypochondriasis, or OCD, were related to attrition. Less attrition was associated with greater years from the onset of the first episode of depression.

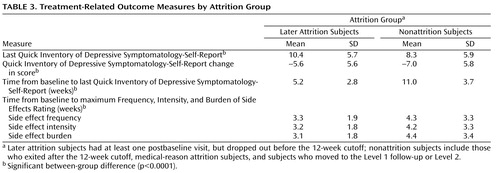

Table 2 and Table 3 illustrate treatment-related characteristics for subjects in the later attrition and nonattrition groups. Compared with individuals in the nonattrition group, subjects in the later attrition group dropped out with greater severity of depressive symptoms; lower side effect frequency, intensity, and overall burden; and lower doses of citalopram at the last measurement occasion prior to leaving the study.

Discussion

In this large representative cohort, approximately one-quarter of the participants who entered the trial dropped out before their 12-week visit. Of these, approximately one-third discontinued treatment after only the baseline visit.

African Americans were more likely to exit than Caucasians, particularly after returning at least once after baseline. Subjects in the attrition groups were also younger and had less education. For example, for each 10 additional years of age, the odds of a patient dropping out were lower by a factor of 0.76.

The size of the current study cohort and its generalizability to patients treated in typical practices suggest that African Americans and those who are disadvantaged by youth and less education may less likely continue in treatment, at least in treatment delivery systems similar to those included in this study. Younger patients, racial/ethnic minority patients, and those patients with fewer years of education have been shown to drop out more in clinical trials (11 , 12 , 14) . There could, however, be an association between race or ethnicity with the quality of the patient/provider relationship, treatment acceptability or setting, efficacy of treatment, or other issues that were not considered in the present study.

Illness-related factors also played a role in attrition. Patients presenting with the experience of at least one prior depressive episode were at less risk of dropping out. This is consistent with observations from a study conducted by Bull et al. (32) , which showed that patients who had previously taken an antidepressant were 33% less likely to discontinue their SSRI than those with no prior antidepressant treatment.

Why might experience with recurrent depression be associated with less attrition? In major depressive disorder, the impact of poor adherence on symptomatic worsening is delayed. Perhaps greater retention of participants with more major depressive disorder experience was because of greater participant recognition of the consequence of living with depression (i.e., depressed individuals better understand the risk of recurrence and the need for continued treatment). These participants may also have the experience to know that episodes can resolve with treatment and may be more hopeful, although the responses to study baseline questions that addressed expectations about improvement with treatment were not associated with attrition.

Of interest, features such as gender, marital status, total number of episodes of depression, or treatment setting (primary versus psychiatric settings) were not related to attrition. The latter result could be explained by the fact that similar patients were treated in both settings with similar treatments. The severity of illness also was not meaningfully related to attrition, given the small numerical differences in baseline depression severity between patients in the attrition and nonattrition groups.

Although they did not meet the a priori threshold for significance, several population and illness-related tendencies appeared to be clinically meaningful. A second minority status, Hispanic ethnicity, may be associated with attrition. Similar to African Americans, attrition among Hispanic patients was more likely to occur later in treatment, after returning at least once after baseline. Those patients with an additional disadvantage, public insurance, and those with more concurrent psychiatric comorbidities, especially three or more, were also more likely to drop out, both immediately and later in treatment.

Finally, patients with more years since the onset of their first episode of depression (15.7 versus 12.7 years) were more likely to remain in treatment, which is consistent with the finding that those patients with recurrent depression drop out less than those in their first episode. This finding could, however, be related to older age.

The findings in the present study suggest that in both clinical trials and clinical practice, several time points in the major depressive disorder treatment process may provide opportunities to engage and encourage populations at higher risk for attrition. Special outreach may be directed toward younger patients, the educationally disadvantaged, and possibly those with public insurance. Attention toward retaining African American patients and possibly Hispanic patients is also particularly indicated as treatment proceeds. This outreach may also occur for those patients with a presentation of illness that suggests a higher risk for attrition—being in the first major depressive episode and likely having multiple psychiatric comorbidities. During outreach, individual barriers to continuation, which could span a broad range of issues, may be elicited and addressed as feasible with each patient.

For those patients in their first major depressive episode or with fewer years of experience with major depressive disorder, clinicians and clinical staff can take additional steps during initial visits to educate these patients. Vigorous interventions that focus on education about depression, its frequently chronic or recurrent course, expectations of treatment, the consequences of attrition, and the importance of judging progress with an objective measurement-based appraisal of symptoms and functioning may help substitute for experience with depression and help inoculate patients against dropping out.

One alternative for both high-risk populations and those patients with a high-risk presentation of illness is to use more aggressive forms of treatment earlier in the treatment process in order to increase the likelihood of efficacy earlier in treatment, which may also serve to reduce dropout rates. Another intervention that may help to identify those individuals at high-risk is to ask questions about patients’ likelihood of returning for future visits (33) in order to signal the need for more intensive retention efforts.

Since, in the present study, the average times from baseline to the last measurement occasion for the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self-Rated were rather different (over 5 weeks) and the average times to the maximum Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating were also different between the later attrition and nonattrition groups, discussion of treatment-related characteristics of patients in the attrition groups can only be descriptive.

Not surprisingly, the comparison of those subjects in the later attrition group with those in the nonattrition group showed greater depressive severity at exit in the attrition subjects. This comparison also revealed lower dosing, along with less side effect frequency, intensity, and burden in patients in the later attrition group relative to those in the nonattrition group, which was expected given the shorter time in treatment for individuals in the later attrition group. It is also possible that patients with intolerable side effects had this experience after the last available measurement occasion and left the study before the increase could be measured.

This study has several limitations, including features that could limit generalizability to clinical practices or efficacy trials. These features included the option to change treatments as early as the fourth week if treatment was intolerable or response was unsatisfactory; the vigorous, consistently monitored dosing required by the protocol; the use of clinical research coordinators to assist the participants and physicians with educational, supportive, and adherence monitoring; and the provision of antidepressant medication and visits for uninsured participants at no cost.

The study did not address the impact on attrition of many factors that arise during treatment, such as improvement in quality of life or participant perception of efficacy. Even the current description of the impact of side effects or the lack of efficacy in the attrition groups was limited by the STAR*D study design, which excluded patients with prior intolerable side effects with citalopram and allowed transition to the next treatment step rapidly because of intolerable side effects or lack of efficacy. Additionally, the study did not address clinician factors, such as the quality of care; patient/clinician match; medication factors, such as the complexity of the regimen; clinic access issues; costs; or other perceptual/attitudinal factors, such as clinical investment that could influence dropout or differentially influence patients with specific characteristics. Interventions to retain participants may have been somewhat variable across treatment settings, although a procedural manual, multiple face-to-face training meetings, frequent supervisory conference calls, and monitoring of procedural consistency attempted to minimize variability.

The findings presented in this study highlight the need to define and implement measures to reduce attrition during the very important acute phase of treatment with antidepressant medications, thereby potentially reducing impairment caused by depression.

1. Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, Leong SA, Lowe SW, Berglund PA, Corey-Lisle PK: The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1465–1475Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003; 289:3095–3105Google Scholar

3. Kocsis J, Klein DN: Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Depression. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

4. Depression Guideline Panel: Treatment of major depression, in Depression in Primary Care, Vol. 2, Clinical Practice Guideline, Number 5. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, and Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Rockville, Md, AHCPR Publication 93–0551, 1993Google Scholar

5. Hirschfeld RM, Dunner DL, Keitner G, Klein DN, Koran LM, Kornstein SG, Markowitz JC, Miller I, Nemeroff CB, Ninan PT, Rush AJ, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, Borian FE, Crits-Christoph P, Keller MB: Does psychosocial functioning improve independent of depressive symptoms? a comparison of nefazodone, psychotherapy, and their combination. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:123–133Google Scholar

6. Rush AJ, Kraemer HC, Sackeim HA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Frank E, Ninan PT, Thase ME, Gelenberg AJ, Kupfer DJ, Regier DA, Rosenbaum JF, Ray O, Schatzberg AF: Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006; 31:1841–1853Google Scholar

7. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, Norquist G, Howland RH, Lebowitz B, McGrath PJ, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Balasubramani GK, Fava M: Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:28–40Google Scholar

8. Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Kennedy S, Sredl K: The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:1128–1132Google Scholar

9. Sabaté E: Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2003Google Scholar

10. Demyttenaere K, Enzlin P, Dewe W, Boulanger B, De Bie J, De Troyer W, Mesters P: Compliance with antidepressants in a primary care setting, I: beyond lack of efficacy and adverse events. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 22):30–33Google Scholar

11. Demyttenaere K, Van Ganse E, Gregoire J, Gaens E, Mesters P: Compliance in depressed patients treated with fluoxetine or amitriptyline. Belgian Compliance Study Group. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 13:11–17Google Scholar

12. Last CG, Thase ME, Hersen M, Bellack AS, Himmelhoch JM: Patterns of attrition for psychosocial and pharmacologic treatments of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1985; 46:361–366Google Scholar

13. Tedlow JR, Fava M, Uebelacker LA, Alpert JE, Nierenberg AA, Rosenbaum JF: Are study dropouts different from completers? Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:668–670Google Scholar

14. Arnow BA, Blasey C, Manber R, Constantino MJ, Markowitz JC, Klein DN, Thase ME, Kocsis JH, Rush AJ: Dropouts versus completers among chronically depressed outpatients. J Affect Disord 2007; 97:197–202Google Scholar

15. Beasley CM Jr, Koke SC, Nilsson ME, Gonzales JS: Adverse events and treatment discontinuations in clinical trials of fluoxetine in major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Clin Ther 2000; 22:1319–1330Google Scholar

16. Vis PM, van Baardewijk M, Einarson TR: Duloxetine and venlafaxine-XR in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39:1798–1807Google Scholar

17. Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Sackeim HA, Quitkin FM, Wisniewski S, Lavori PW, Rosenbaum JF, Kupfer DJ: Background and rationale for the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003; 26:457–494Google Scholar

18. Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Lavori PW, Trivedi MH, Sackeim HA, Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Quitkin FM, Kashner TM, Kupfer DJ, Rosenbaum JF, Alpert J, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Lebowitz BD, Ritz L, Niederehe G: Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials 2004; 25:119–142Google Scholar

19. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Google Scholar

20. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, Markowitz JC, Ninan PT, Kornstein S, Manber R, Thase ME, Kocsis JH, Keller MB: The 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), Clinician Rating (QIDS-C), and Self-Report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:573–583Google Scholar

21. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Suppes T, Crismon ML, Shores-Wilson K, Toprac MG, Dennehy EB, Witte B, Kashner TM: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med 2004; 34:73–82Google Scholar

22. Wisniewski S, Rush, AJ, Balasubramani GK, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA, for the STAR*D Investigators: Self-Rated Global Measure of the Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects. J Psychiatr Pract 2006; 12:71–79Google Scholar

23. Wisniewski SR, Eng H, Meloro L, Gatt R, Ritz L, Stegman D, Trivedi M, Biggs MM, Friedman E, Shores-Wilson K, Warden D, Bartolowits D, Martin JP, Rush AJ: Web-based communications and management of a multi-center clinical trial: the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) project. Clin Trials 2004; 1:387–398Google Scholar

24. Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, Rifai AH, Mulsant B, Reynolds CF 3rd: Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res 1992; 41:237–248Google Scholar

25. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI: The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire: development, reliability and validity. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:175–189Google Scholar

26. Novick JS, Stewart JW, Wisniewski SR, Cook IA, Manev R, Nierenberg AA, Rosenbaum JF, Shores-Wilson K, Balasubramani GK, Biggs MM, Zisook S, Rush AJ: Clinical and demographic features of atypical depression in outpatients with major depressive disorder: preliminary findings from STAR*D. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:1002–1011Google Scholar

27. Khan AY, Carrithers J, Preskorn SH, Wisniewski SR, Lear R, Rush AJ, Stegman D, Kelley C, Kreiner K, Nierenberg AA, and Fava, M: Clinical and demographic factors associated with DSM-IV melancholic depression. Annals of Clin Psychiatry 2006; 18:91–98Google Scholar

28. Fava M, Alpert JE, Carmin CN, Wisniewski SR, Trivedi MH, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Morgan D, Schwartz T, Balasubramani GK, Rush AJ: Clinical correlates and symptom patterns of anxious depression among patients with major depressive disorder in STAR*D. Psychol Med 2004; 34:1299–1308Google Scholar

29. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34:220–233Google Scholar

30. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:321–326Google Scholar

31. Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH: The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180:461–464Google Scholar

32. Bull SA, Hunkeler EM, Lee JY, Rowland CR, Williamson TE, Schwab JR, Hurt SW: Discontinuing or switching selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36:578–584Google Scholar

33. Leon AC, Mallinckrodt CH, Chuang-Stein C, Archibald DG, Archer GE, Chartier K: Attrition in randomized controlled clinical trials: methodological issues in psychopharmacology. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:1001–1005Google Scholar