Neurocognitive Function in Unmedicated Manic and Medicated Euthymic Pediatric Bipolar Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A systematic evaluation of neuropsychological functioning in individuals with pediatric bipolar disorder is necessary to clarify the types of cognitive deficits that are associated with acutely ill and euthymic phases of the disorder and the effects of medication on these deficits. METHOD: Unmedicated (N=28) and medicated (N=28) pediatric bipolar patients and healthy individuals (N=28) (mean age=11.74 years, SD=2.99) completed cognitive testing. Groups were matched on age, sex, race, parental socioeconomic status, general intelligence, and single-word reading ability. A computerized neurocognitive battery and standardized neuropsychological tests were administered to assess attention, executive function, working memory, verbal memory, visual memory, visuospatial perception, and motor skills. RESULTS: Subjects with pediatric bipolar disorder, regardless of medication and illness status, showed impairments in the domains of attention, executive functioning, working memory, and verbal learning compared to healthy individuals. Also, bipolar subjects with comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) performed worse on tasks assessing attention and executive function than patients with bipolar disorder alone. CONCLUSIONS: The absence of differences in the deficits of neurocognitive profiles between acutely ill unmedicated patients and euthymic medicated patients suggests that these impairments are trait-like characteristics of pediatric bipolar disorder. The cognitive deficits found in individuals with pediatric bipolar disorder suggest significant involvement of frontal lobe systems supporting working memory and mesial temporal lobe systems supporting verbal memory, regardless of ADHD comorbidity.

Pediatric bipolar disorder exhibits significant and persistent functional disability associated with chronic course and poor interepisodic recovery (1). Given the potentially different neurocognitive deficits that might be associated with acute illness and the recovery phase, it is important to determine if these deficits persist across illness states and to characterize functional disability after symptomatic recovery. This information has implications both for understanding the pathophysiology of the illness and also for educational planning for affected children. Most current knowledge about neurocognitive function in bipolar disorder is based on findings from adult studies indicating impairment in set shifting and sustaining attention, working memory, verbal memory, and executive function (2–7). There are several difficulties in inferring that neurocognitive function in adult bipolar disorder is similar to that found in pediatric bipolar disorder. First, neurocognitive capacity is constantly changing in the developing brain, so the impact of illness on functional brain systems can be different in children than in adults (8, 9). Second, children with pediatric bipolar disorder are typically taking multiple medications, more so than adults (10). Several of the mood stabilizers as well as other psychotropic medications, especially given in high doses, may influence cognitive function and/or cause sedation (11). Third, the presence of a high rate of comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (12) in youth with pediatric bipolar disorder makes it difficult to identify deficits specific to pediatric bipolar disorder, especially given the cortical-striatal systems that are reported to underlie ADHD (13–17) are also implicated in bipolar disorder (4).

Recently, several small studies have examined neurocognitive function in pediatric bipolar disorder (16–21). Central findings from these studies include impairment in attention (16, 17), set shifting (16, 20), visuospatial memory (16, 18), processing speed and interference control (17), verbal memory (17, 20, 21), and abstract problem solving or executive function (17, 22). Performance IQ with the WISC was reported to be lower in pediatric bipolar disorder than in ADHD, conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder and similar to that seen in schizophrenia spectrum disorders (19). Furthermore, in a prospective study of offspring who developed bipolar disorder, Meyer and colleagues (20) reported similar findings of lower performance IQ in patients with pediatric bipolar disorder than in unipolar depression. Overall, methodological difficulties in these pioneering studies included small group sizes (18, 20), failure to match groups on key variables, such as IQ (20, 21), inclusion of subjects in heterogeneous clinical states (e.g., hypomanic, manic, euthymic, or depressed) (16–21), failure to account for possible effects of multiple medications (16–21), and failure to correct for multiple comparisons in statistical analyses (17). None of the studies examined neurocognitive function with and without medication with the same battery in acutely ill and euthymic groups.

Acute illness status and medication effects are some of the key factors that can affect neurocognitive function. Some studies showed that the impairment in the manic state (22–24) was less than in euthymic adult bipolar disorder patients in the domains of visuospatial memory, executive function (5, 25), and vigilance (26). Improvement in cognition with symptom remission was not always found to be uniform across neuropsychological domains. For example, McGrath and colleagues (23) reported improvement on remission in executive function but not in the domains of attention, inhibition, and psychomotor speed. These findings suggest that some level of cognitive impairment remains after periods of acute illness (27). Additionally, when the effects of medication on neurocognitive function were the focus of studies, results are equivocal with both mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics. Although some studies report improvement with specific medications in areas such as attention, working memory, and executive function (17), not all studies indicate that. Furthermore, there is considerable complexity related to interpretation of results given the confounding role of comorbid disorders, length of treatment, and symptom status at the time of assessment.

Given the high incidence of ADHD comorbidity in pediatric bipolar disorder compared to adult bipolar disorder, several studies of pediatric bipolar disorder have addressed the role of comorbid ADHD on neurocognitive function. Dickstein and colleagues (16) reported that 57% of their pediatric bipolar disorder group had current ADHD. They did not detect differences in nonverbally based tests in pediatric bipolar disorder in individuals with and those without ADHD. McClure and colleagues (21) reported greater impairment of verbal memory in their pediatric bipolar disorder group that was comorbid with ADHD compared to those with pediatric bipolar disorder alone. Their report of a lack of impairment in verbal memory in subjects with pediatric bipolar disorder without ADHD (2–5) is in sharp contrast to adult studies of bipolar disorder that showed prominent impairment in memory function. In summary, despite methodological limitations and varied tests, the majority of the available data point to similar neurocognitive profiles in pediatric bipolar disorder, irrespective of comorbid ADHD.

Therefore, building on prior neurocognitive findings from pediatric and adult bipolar disorder studies (4, 7), we predicted that 1) neurocognitive deficits are found in pediatric bipolar disorder in the domains of attention, working memory, verbal memory, visual memory, executive function, visuospatial perception, and motor skills; 2) unmedicated acutely ill patients would perform worse than euthymic medicated patients in neurocognitive function; 3) euthymic medicated pediatric bipolar disorder subjects will demonstrate cognitive deficits relative to healthy individuals; and 4) there are no neurocognitive differences between the pediatric bipolar disorder individuals with and without comorbid ADHD.

Method

Subjects

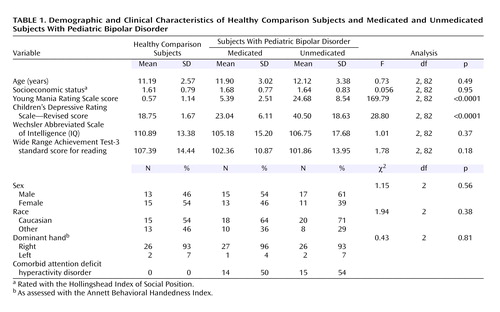

The study group consisted of three groups of 8–17-year-old subjects matched on age, sex, race, socioeconomic status, intelligence, and word-reading ability. They were 28 healthy comparison subjects, 28 subjects with unmedicated pediatric bipolar disorder, and 28 subjects with medicated euthymic pediatric bipolar disorder. Inclusion criteria for the unmedicated pediatric bipolar disorder group were a Young Mania Rating Scale (28) score of ≥20, bipolar disorder type I, mixed or manic state, with at least 1 week of a drug-free period before neurocognitive testing. Medicated pediatric bipolar disorder patients were euthymic subjects who were responders from a recently completed clinical trial that tested the efficacy of lithium plus risperidone (N=14) versus divalproex plus risperidone (N=14) (28). Mean risperidone doses in the lithium plus risperidone group and the divalproex sodium plus risperidone group were 0.75 mg/day (SD=0.75) and 0.70 mg/day (SD=0.67), respectively. The mean dose of divalproex sodium was 925 mg/day (SD=325) (106 μg/dl), and the mean dose of lithium carbonate was 750 mg/day (SD=400) (0.9 meq/liter). At the time of testing, the euthymic pediatric bipolar disorder group had Young Mania Rating Scale scores ≤8 and Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised (29) scores ≤30. All met DSM-IV criteria for bipolar disorder type I. We included subjects who manifested at least two of the three core symptoms of pediatric bipolar disorder (i.e., elated mood, irritability, and grandiosity). For example, if a subject appeared in an irritable mood without elated mood or grandiosity, he or she was excluded. There were nearly equal numbers of subjects with comorbid ADHD in the two pediatric bipolar disorder groups (Table 1). The healthy comparison subjects were also euthymic, with Young Mania Rating Scale scores ≤8 and Children’s Depressive Rating Scale—Revised scores of ≤40. No healthy subject met DSM-IV criteria for a major psychiatric disorder. See Table 1 for a summary of demographic and clinical variables.

Exclusion criteria for the entire group were active substance abuse, serious medical problems, IQ <70 as determined by the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, or the presence of another DSM-IV axis I diagnosis that required use of any concomitant therapy. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Verbal or written assent was provided by all children in addition to the written informed consent by the parents.

Clinical and Neurocognitive Evaluation

Each child and at least one of their parents were interviewed by using the Washington University, St. Louis, Mo., Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) by doctoral-level research clinicians (30). Clinical information from all available sources was combined to provide a consensus clinical diagnosis. The WASH-U-KSADS interviews, as well as those of the Young Mania Rating Scale and the Children’s Depressive Rating Scale—Revised, were completed by trained raters who had no knowledge of cognitive test performance. Kappa was at least 0.96 for the total scores on the rating scales.

Intellectual and neuropsychological tests were performed by postdoctoral researchers with joint supervision from a psychologist and a child psychiatrist. The battery consisted of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, the Trail Making Tests A and B, the spatial span and digit span subtests from the Wechsler Memory Scale, 3rd ed., and the California Verbal Learning Test—Child Version. The computerized neurocognitive battery was compiled from the University of Pennsylvania Computerized Battery (29) and Cogtest (30). Tests selected from the Penn battery included the Penn Conditional Exclusion Test, the Penn Continuous Performance Test, the Penn Face Memory Test, and the Penn Computerized Judgment of Line Orientation. The tests selected from the Cogtest battery included the Set Shifting Test, the Controlled Oral Word Association Test, and the test of finger tapping speed. To provide a standard metric for comparison across neurocognitive domains, test scores were standardized (by using z scores) to the performance of the healthy group. Summary measures were calculated for executive function, attention, working memory, verbal memory, visual memory, motor skills, and visual-spatial perception. Each summary or composite measure represented the average of individual tests representative of that specific neurocognitive domain. Internal consistency of scores comprising each neurocognitive domain was calculated by using Cronbach’s alpha; the scores are also presented in Table 2. Global neurocognitive function score was estimated by averaging the means of the seven composite scores.

Results

Clinical Features

Mean age at onset was 7.2 years (SD=4) in pediatric bipolar disorder subjects, and duration of illness was 34 months (SD=8), with no significant group differences between medicated and unmedicated subjects with either of these variables (t=1.1, df=53, p>0.05). However, as expected, significant group differences were found on the Young Mania Rating Scale and the Children’s Depressive Rating Scale—Revised scores. The medicated pediatric bipolar disorder group showed higher scores than the healthy subjects (t=–9.2, df=38, p<0.0001) but lower scores than the unmedicated pediatric bipolar disorder group on the Young Mania Rating Scale (t=–11.4, df=32, p<0.0001). On the Children’s Depressive Rating Scale—Revised, there were no significant differences between the healthy and medicated pediatric bipolar disorder groups. The unmedicated pediatric bipolar disorder group had significantly more depressive symptoms than the medicated pediatric bipolar disorder and the healthy comparison groups (t=5.4, df=82, p<0.0001). The average baseline Young Mania Rating Scale score of currently euthymic subjects before treatment was 29.4 (SD=4.0), which did not differ from the scores of the acutely ill group at the time that group was tested for this study (t=1.2, df=53, p>0.05). Thus, although the two patient groups differed in symptom severity at the time of testing, they were alike in manic symptom severity when acutely ill. Furthermore, when they were acutely ill, there were 35 (63%) with a manic episode and 21 (37%) with a mixed episode among all pediatric bipolar disorder subjects, with no significant group differences (t=1.3, df=53, p>0.05).

Neurocognitive Comparisons

To maintain experiment-wise type I error rates, our primary statistical analyses involved omnibus testing for overall group differences and group profile differences. Univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were then conducted to compare the groups across each domain. Significant univariate findings were followed by post hoc pairwise group comparisons for individual scores with Tukey corrections. Repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) conducted to test for overall group differences and group profile differences showed significant overall group differences in performance across all domains (F=9.21, df=2, 81, p<0.0001). There was also a significant interaction between diagnosis and neurocognitive function (F=2.70, df=12, 154, p=0.002), indicating that the profile of abilities across domains differed across groups. We conducted univariate ANOVA for each domain of the neurocognitive function to clarify the two-way interaction. There were significant differences between subject groups in performance on attention, executive function, working memory, and verbal memory composites but not in visuospatial perception, visual memory, or motor skills. Post hoc analysis with the Tukey procedure revealed that attention, executive function, working memory, and verbal memory were impaired in pediatric bipolar disorder groups with and without medication relative to the healthy subjects. There were no significant differences between the two pediatric bipolar disorder groups on any domain (Table 3). In addition, we examined differences in the euthymic group between those maintained with lithium plus risperidone versus those taking divalproex sodium plus risperidone. There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups on any of the neurocognitive domains.

We also examined the relationship between symptoms and neurocognitive function separately in the patient groups. Spearman correlations showed no significant relationship between overall cognitive functioning (based on the global summary score created by averaging domain scores) and Young Mania Rating Scale (rs=–0.19, n.s.) or Children’s Depressive Rating Scale—Revised scores (rs=–23, n.s.). In the medicated pediatric bipolar disorder group, a Spearman’s correlation between overall neurocognitive function and the Young Mania Rating Scale was –14 (n.s.), and with the Children’s Depressive Rating Scale—Revised, it was –0.21 (n.s.).

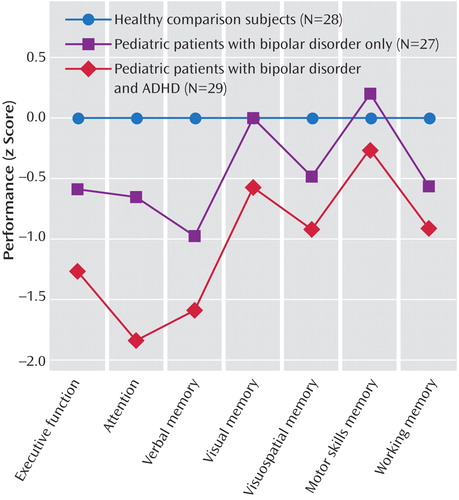

In secondary analyses, we compared the healthy comparison subjects, the subjects with pediatric bipolar disorder without ADHD, and the subjects with pediatric bipolar disorder with ADHD with the pediatric bipolar disorder patients sorted without regard to medication or illness status (Figure 1). There were no significant differences between the two pediatric bipolar disorder groups in the type or amount of medication received. Repeated-measures MANOVAs showed significant differences between subject groups (F=14.64, df=2, 81, p<0.0001). A significant interaction was observed between diagnosis and neurocognitive function (F=2.97, df=12, 154, p<0.0001). Follow-up univariate analysis revealed significant differences between the pediatric bipolar disorder group with ADHD and the group without ADHD, with the comorbid group being significantly more impaired on attention, executive function, and visual memory domains. Working memory and verbal memory composites were significantly impaired in pediatric bipolar disorder groups with and those without ADHD relative to healthy individuals, but there were no differences in the pediatric bipolar disorder subjects with regard to comorbid ADHD status. There were no significant differences across the three groups in motor skills.

To account for the contribution of development in interpreting results, we factored in age as a covariate. Although age was a significant factor (F=58.9, df=1.80, p<0.001), the group differences remain unchanged across the domains.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare the neurocognitive profile of acutely ill unmedicated and medicated euthymic bipolar youth. There are several significant findings from this study. First, the data document neurocognitive deficits in pediatric bipolar disorder in the domains of sustained attention, working memory, verbal memory, and executive function. Second, the impairment in affected domains was present in both the acutely ill and remitted patient groups, suggesting that these deficits persist regardless of the illness state or medication status. A third finding was the significantly greater impairment in attention and executive function in pediatric bipolar disorder subjects with comorbid ADHD compared to those with pediatric bipolar disorder alone.

Consistent with the previous studies of adult (4, 5, 7, 25, 26) and pediatric cases (16–20) of bipolar disorder, performance on tasks with high cognitive demand, such as executive deficits in shifting attention, processing speed, and problem solving, is affected in our study, suggestive of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex dysfunction. Working memory deficits have also been reported in studies of adults with bipolar disorder (4). Components of working memory have been divided into object identification and object location corresponding selectively to information processing in the ventral stream, involving the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, and the dorsal stream, involving the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (31). The current study, indicating the spatial span task that tests object location, may correspond to the dysfunction in the underlying dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Deficits in declarative verbal memory were observed in pediatric bipolar disorder subjects, which is similar to findings reported in other pediatric (17, 18, 21) and adult studies (2, 3).

However, unlike Rubinsztein and colleagues (5) in their study of adult bipolar disorder, and as reported by Dickstein and colleagues (16) and Olvera and colleagues (18) in pediatric bipolar disorder, we did not find visuospatial abnormalities in our pediatric group. It may be that visuospatial perception tested with the Penn Computerized Judgment of Line Orientation task is different from the visuospatial abnormalities reported by previous studies. For example, the Spatial Span task on CANTAB that assesses visuospatial working memory is not a measure of simple visuospatial perception (7, 16). McClure and colleagues (21) examined the visuospatial recall and reconstruction of a standardized figure and reported no significant impairment in subjects with pediatric bipolar disorder. They also tested facial recognition memory, similar to what was done in the present study, and reported no significant group differences in visuospatial memory, similar to our findings. The fact that there are mixed findings with regard to visuospatial abnormalities in adult (5, 7), as well as pediatric (16, 18, 21), studies in this domain appears to be largely because of variation in tasks and use of varied terminology across divergent but partially overlapping concepts. One tentative conclusion about this literature is that deficits in visuospatial processing may be restricted, or perhaps more prominent, when complex operations are performed with spatial information beyond the more restricted demands of visual perception.

In adult bipolar disorder, studies assessing the influence of manic or depressive state on neurocognitive performance have yielded mixed results (5, 22–26). In the present study, illness status (acutely ill or euthymic) and medication status (lithium plus risperidone versus divalproex sodium plus risperidone) appeared to play a minimal role in influencing the severity and nature of cognitive deficits associated with pediatric bipolar disorder. Based on the findings from studies of bipolar disorder in adults (4), we expected that residual affective symptoms may affect cognitive performance in pediatric bipolar disorder. Therefore, we observed stringent criteria of Young Mania Rating Scale scores of ≤8 and Children’s Depressive Rating Scale—Revised scores of ≤40 to minimize the affect of affective symptoms influencing neurocognitive task performance in the euthymic medicated group. Contrary to our third hypothesis that cognitive deficits would be less prominent in the treated euthymic patients, the results did not reveal less significant impairment in euthymic patients. As has been noted in some studies of adults with bipolar disorder, we found impairment in both medicated euthymic and unmedicated ill subjects in comparison to healthy comparison groups in the areas of verbal memory, executive functioning (22), and sustained attention (3).

A limitation of this study, however, is the use of two separate cross-sectional groups of medicated and unmedicated patients instead of the more ideal longitudinal follow-up of untreated patients through controlled treatment. Therefore, our findings cannot be conclusive in confirming that medication treatment and illness status have no influence on neurocognitive difficulties in pediatric bipolar disorder. With regard to potential medication effects, the effects of treatment with lithium (32, 33) and anticonvulsants (11) on neurocognitive function in adult bipolar disorder have been variable. Recent evidence indicates that an optimum serum level of lithium, as was the case in our study, is less likely to adversely affect cognition (33). As to potential risperidone effects, as was previously mentioned, the majority of the evidence points to improved neurocognitive dysfunction with treatment with antipsychotic medications in adult bipolar disorder (11). But in our pediatric group, treated euthymic patients performed no better than acutely ill unmedicated patients. It is both intriguing and disappointing to note the similar pattern of neurocognitive deficits in unmedicated manic subjects and patients who were medicated and clinically stable. This argues that the poorer performance of the treated patients is not a result of the adverse effects of treatment and that the deficits themselves do not appear to be responsive to state-of-the-art treatment.

In addition to the illness state and medication, comorbid ADHD may potentially influence the neurocognitive profile of pediatric bipolar disorder subjects. Recently, Meyer et al. (20) found that 67% of the adults with bipolar disorder showed deficits on tasks of attention during adolescence before being diagnosed with bipolar disorder. It is indeed unclear if ADHD symptoms are inherent to pediatric bipolar disorder or if they should be construed as a separate comorbid condition (3). A number of recent studies of pediatric bipolar disorder have reported persistent deficits in attention irrespective of comorbid ADHD (16, 17, 19, 21). Contrary to our hypothesis and findings from some previous pediatric bipolar disorder studies, we found greater neurocognitive dysfunction in pediatric bipolar disorder subjects with comorbid ADHD. Problems of attention and executive function were the specific domains in which there were greater deficits in the group with both pediatric bipolar disorder and ADHD. It may be that frontostriatal systems involved in ADHD are also affected in pediatric bipolar disorder with ADHD, with consequent impairments in similar attentional subsystems in patients with pediatric bipolar disorder who also meet criteria for ADHD. Furthermore, the prefrontal and mesial temporal lobe circuitry that underlies the working memory and verbal memory may be specifically involved in pediatric bipolar disorder because impairments in these functions were associated with pediatric bipolar disorder irrespective of ADHD status.

Our findings indicating differences among the pediatric bipolar disorder groups with and without ADHD are consistent with the results of adult studies (2–5) but stand in contrast to the findings from McClure and colleagues (21) in which subjects with pediatric bipolar disorder without ADHD did not show impairment compared to those with ADHD. However, it is important to note that impairment in a comorbid group cannot be unequivocally attributed to ADHD alone in their group. In view of our results and discordant with those of previous studies, a careful further exploration of underlying functional brain systems in pediatric bipolar disorder, ADHD, and pediatric bipolar disorder plus ADHD is warranted to better delineate overlapping and specific cognitive neural system deficits associated with pediatric bipolar disorder and ADHD.

The strengths of this study include a relatively large size in each group, restriction of the group to the diagnosis of bipolar disorder type I, exclusion of children below 8 years of age to minimize the confounding effect of considerable cognitive immaturity of relevant neurocognitive systems in early childhood, and the careful matching of study groups on demographic characteristics, intelligence, and reading ability. This study provides essential data and a framework for understanding the cognitive deficits found in pediatric bipolar disorder that have direct clinical implications. Patients with pediatric bipolar disorder show deficits in a variety of cognitive areas, suggesting that abnormalities are affecting multiple neocortical and cognitive systems. The abilities to sustain and shift attention; to learn, remember, and reproduce verbal information; to exert inhibitory control; and to organize complex responses that are shown to be impaired in this population are critical for success in school. These deficits need to be recognized and incorporated in individual educational plans and school interventions for youth with pediatric bipolar disorder, and they need to be considered a treatment target for interventions in this disorder.

|

|

|

Received May 25, 2005; revision received July 20, 2005; accepted Aug. 18, 2005. From the Center for Cognitive Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Pavuluri, Center for Cognitive Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, 912 South Wood St. (M/C 913), Chicago, IL 60612; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by an NIH/NCRR K23 RR-018638-01 grant awarded to Dr. Pavuluri and a Marshall Reynold Foundation grant awarded to Drs. Sweeney and Pavuluri.

Figure 1. Performance Across Seven Neurocognitive Domains of Healthy Comparison Subjects and Patients With and Patients Without Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Comorbidity

1. Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K: Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:459–467Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Cavanaugh JTO, Van Beck M, Muri W, Blackwood DHR: Case-control study of neurocognitive function in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder: an association with mania. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180:320–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Clark L, Goodwin GM: State- and trait-related deficits in sustained attention in bipolar disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 254:61–68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Ferrier IN, Thompson JM: Cognitive impairment in bipolar affective disorder: implication for the bipolar diathesis. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 18:293–295Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Rubinsztein JS, Fletcher PC, Rogers RD, Ho LW, Aigbirhio FI, Paykel ES, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ: Decision-making in mania: a PET study. Brain 2000; 124(part 12):2550-2563Google Scholar

6. Thompson JM, Gallagher P, Hughes JH, Watson S, Gray JM, Ferrier IN, Young AH: Neurocognitive impairment in euthymic patients with bipolar affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 186:32–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ: Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:674–684Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Luna B, Sweeney JA: Studies of brain and cognitive maturation through childhood and adolescence: a strategy for testing neurodevelopmental hypothesis. Schizophr Bull 2001; 27:443–455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Stoll AL, Renshaw PF, Yurgelun-Todd DA, Cohen BM: Neuroimaging in bipolar disorder: what have we learned? Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:505-517; correction, 2001; 49:80Google Scholar

10. Biederman J, Faraone S, Mick E, Wozniak J, Chen L, Oullette C, Marrs A, Moore P, Garcia J, Mennin D, Lelon E: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and juvenile mania: an overlooked comorbidity? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:997–1008Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Macqueen G, Young T: Cognitive effects of atypical antipsychotics: focus on bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord 2003; 5(suppl 2):53-61Google Scholar

12. Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Del Bello MP, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, Frazier J, Beringer L, Nickelsburg MJ: DSM-IV mania symptoms in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype compared to attention deficit hyperactive and normal controls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 12:11–25Google Scholar

13. Bush G, Frazier JA, Rauch SL, Seidman LJ, Whalen PJ, Jenike MA, Rosen BR, Biederman J: Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder revealed by fMRI and the Counting Stroop. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:1542–1552Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Casey BJ, Castellanos FX, Giedd JN, Marsh WL, Hamburger SD, Schubert AB, Vauss YC, Vaituzis AC, Dickstein DP, Sarfatti SE, Rapoport JL: Implication of right frontostriatal circuitry in response inhibition and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:374–383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Rubia K, Overmeyer S, Taylor E, Brammer M, Williams SC, Simmons A, Andrew C, Bullmore ET: Functional frontalisation with age: mapping neurodevelopmental trajectories with fMRI. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2000; 24:13–29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Dickstein DP, Treland JE, Snow J, McClure EB, Mehta MS, Towbin KE, Pine DS, Leibenluft E: Neuropsychological performance in pediatric bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 55:32–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Doyle AE, Wilens TE, Kwon A, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Fried R, Swezey A, Snyder L, Biederman J: Neuropsychological functioning in youth with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58:540–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Olvera RL, Semrud-Clikeman M, Pliszka SR, O’Donnell L: Neuropsychological deficits in adolescents with conduct disorder and comorbid bipolar disorder: a pilot study. Bipolar Disord 2004; 6:1–11Crossref, Google Scholar

19. McCarthy J, Arreses D, McGlashan A, Rappaport B, Kraseki K, Conway F, Mule C, Tucker J: Sustained attention and visual processing speed in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders. Psychol Rep 2004; 95:39–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Meyer SE, Carlson GA, Wiggs EA, Martinez PE, Ronsaville DS, Klimes-Dougan B, Gold W, Radke-Yarrow M: A prospective study of the association among impaired executive functioning, childhood attentional problems, and the development of bipolar disorder. Dev Psychopathol 2004; 16:461–476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. McClure EB, Treland JE, Snow J, Dickstein DP, Towbin KE, Charney DS, Pine DS, Leibenluft E: Memory and learning in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:461–469Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Murphy FC, Sahakina BJ, Rubinsztein JS, Michael A, Rogers RD, Robbins TW, Paykel ES: Emotional bias and inhibitory control processes in mania and depression. Psychol Med 1999; 29:1307–1321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. McGrath J, Scheldt S, Welham J, Clair A: Performance on tests sensitive to impaired executive ability in schizophrenia, mania and well controls: acute and subacute phases. Schizophr Res 1997; 26:127–137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Liu SK, Chiu C-H, Chang C-J, Hwang T-J, Hwu H-G, Chen WJ: Deficits in sustained attention in schizophrenia and affective disorders: stable versus state-dependent markers. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:975–982Link, Google Scholar

25. Altshuler LL, Ventura J, van Gorp WG, Green MF, Theberge DC, Mintz J: Neurocognitive function in clinically stable men with bipolar I disorder or schizophrenia and normal control subjects. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 56:560–569Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Wolfe J, Granholm E, Butters N, WB Saunders E, Janowsky D: Verbal memory deficits associated with major affective disorders: a comparison of unipolar and bipolar patients. J Affect Disord 1987; 13:83–92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. van Gorp WG, Altschuler L, Theberge DC, Mintz J: Declarative and procedural memory in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:525–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Pavuluri MN, Henry DB, Carbray JA, Sampson G, Naylor MW, Janicak PG: Open-label prospective trial of risperidone in combination with lithium or divalproex sodium in pediatric mania. J Affect Disord 2004; 82(suppl 1):S103-S111Google Scholar

29. Gur RC, Ragland JD, Moberg PJ, Turner TH, Bilker WB, Kohler C, Siegel SJ, Gur RE: Computerized neurocognitive scanning, I: methodology and validation in healthy people. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001; 25:766–776Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Cogtest plc. Cogtest: Computerised Cognitive Battery for Clinical Trials. http://www.cogtest.comGoogle Scholar

31. Owen AM, Milner B, Petrides M, Evans AC: Memory for object features versus memory for object location: a positron-emission tomography study of encoding and retrieval processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93:9212–9217Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Stip E, Dufresne J, Lussier I, Yatham L: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of lithium on cognition in healthy subjects: mild and selective effects on learning. J Affect Disord 2000; 60:147–157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Hopkins HS, Gelenberg AJ: Serum lithium levels and the outcome of maintenance therapy of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2000; 2(3, part 1):174-179Google Scholar