Linear Relationship of Valproate Serum Concentration to Response and Optimal Serum Levels for Acute Mania

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Several studies have shown that achieving adequate serum valproate levels is critical to rapid stabilization of acute mania, but estimates of the target therapeutic level have been imprecise. A post hoc analysis of pooled intent-to-treat data from three randomized, placebo-controlled studies of divalproex treatment for acute mania was performed to test a hypothesized linear relationship between serum concentration and response and to determine optimal blood levels for treatment of acute mania. METHOD: Subjects (N=374) were stratified into seven groups (six valproate serum level ranges and placebo), and effect size was determined for each. Linearity of dose response was tested with both parametric and nonparametric techniques. ANOVA was used to compare the response at each serum level range with that of placebo as well as the lowest valproate level (≤55.0 μg/ml). The mean serum valproate level was then determined for all subjects with an effect size greater than or equal to the maximal effect derived from linear modeling. RESULTS: The fit of blood level and response to a linear model was good. Efficacy was significantly greater than placebo beginning at the 71.4–85.0 μg/ml range and for all higher valproate levels; the 94.1–107.0 and >107.0 μg/ml groups were superior to the lowest valproate serum level group. The effect size associated with highest serum levels (>94 μg/ml) was 1.06 (0.59 after placebo correction). Subjects obtaining this effect or greater (N=84) had a mean serum level of 87.5 μg/ml. Blood levels in the lowest effective range were 60% more effective than placebo and in the higher ranges were 120% more effective. Tolerability appeared similar for all groups. CONCLUSIONS: The results of this study suggest that there is a linear relationship between valproate serum concentration and response and that the target blood level of valproate for best response in acute mania is above 94 μg/ml.

Divalproex sodium has been shown in two randomized controlled trials to be an effective treatment for acute mania (1, 2). However, few studies have examined the relationship between serum levels of valproate and efficacy for the treatment of acute mania with divalproex. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline described a broad therapeutic range for trough valproate serum concentrations between 50 and 125 μg/ml (3). An expert consensus guideline recommended a similar broad range with a slightly higher minimum value (mean=58.9 μg/ml, SD=14.9) (4).

A number of studies have suggested that response is related to the blood level or the rise in blood level. In a study of carbamazepine and valproate monotherapy, Vasudev et al. (5) found a significant positive relationship between weekly rise in serum levels and clinical response. Valproate was initiated at 20 mg/kg per day and increased weekly to effect or until maximum serum levels were achieved. Serum valproate levels for these patients ranged from 50–100 μg/ml. There was a positive correlation between change in Young Mania Rating Scale and change in serum levels of valproate at week 2 in this 4-week trial (Pearson’s r=0.64, p<0.05).

A retrospective study investigated the relationship between achieving therapeutic blood levels and time to remission (6). The authors examined 10 potential predictors of remission in manic patients and found that only time to a therapeutic serum level (defined as >50 μg/ml for divalproex) was related to time to remission.

McCoy et al. (7) reviewed the charts of 17 hospitalized patients with refractory bipolar disorder who received valproate augmentation. They collected present diagnosis, diagnosis at illness onset, illness duration, number of hospitalizations, and maximum serum concentration of valproate. Global response was rated once serum valproate reached 50 mg/dl, and patient response was classified as nonresponse or mild, moderate, or marked response. The authors reported a strong trend for those with marked response to have higher serum valproate levels (p<0.068, Wilcoxon ranked sum, two-tailed).

In a pooled analysis of three published studies (1, 8) of orally loaded divalproex (20 or 30 mg/kg per day) versus standard titration, higher divalproex serum concentration was found to be related to earlier efficacy in acute manic patients. Those patients who achieved a serum level of 80 μg/ml by day 3 were found to have statistically greater efficacy at days 3 and 5 than patients who did not achieve this level. There was no difference in tolerability.

Finally, a retrospective study (9) examined 39 inpatients over the age of 60 given valproate. This study included patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder as well as other psychiatric conditions such as agitation in dementia. Nonresponse or partial or full response was assessed with Clinical Global Impression ratings. The authors examined dose and blood levels of valproate in relationship to response. Responders were more likely to carry a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and there was a trend toward responders having higher serum valproate levels than nonresponders. The magnitude of the trend was not reported.

Since manic symptoms are quite disruptive, earlier symptom control is very desirable. The limited evidence available suggests that both the frequency and speed of response are related to a poorly defined blood level. The present study utilized regression analysis and ANOVA in a large pooled data set in an effort to clarify the relationship between serum valproate levels and efficacy in patients treated for acute mania.

Method

Patients

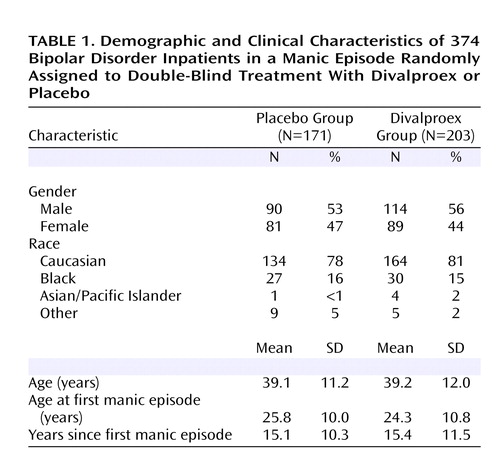

This study pooled 374 patients from three 21-day, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled studies of divalproex sodium in the treatment of acute mania: two published studies of the delayed-release formulation (1, 2) and one unpublished 1999 study from Abbott Laboratories of the extended-release formulation (study report R&D/99/428). Subjects were inpatients diagnosed with an acute manic episode associated with bipolar disorder according to DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria. Each study consisted of a washout/screening period of 1–3 days followed by 21 days of treatment. Divalproex was initiated at 750 mg/day (delayed-release formulation) or 20 mg/kg per day (extended-release formulation) and increased to effect or a maximum serum level of 125 μg/ml. Demographic information for the study group is given in Table 1. To control for differences in study design, the analyses were stratified by study with almost identical results.

Measures

Outcome measures for the three studies were change from baseline on either the Mania Rating Scale or the Young Mania Rating Scale. To allow pooling of the data, responses were converted to effect sizes. The intent-to-treat population was used and the last observation carried forward. The primary efficacy endpoint for the pooled analysis was mean change from baseline to final evaluation transformed into effect size.

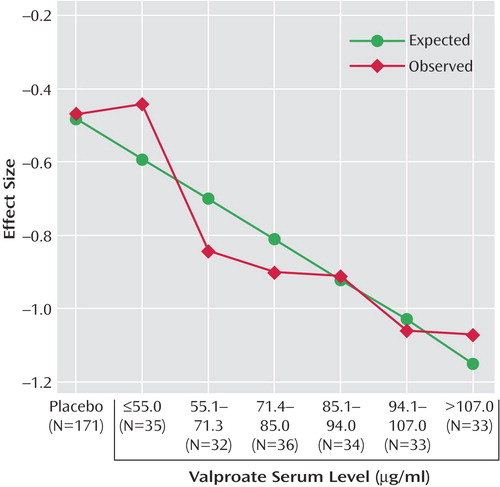

For the purposes of this analysis, subjects were stratified by valproate serum level into four, five, or six groups plus the placebo group. The valproate ranges were derived from the linear modeling procedure, and a linear relationship was found for each stratification strategy. However, division into six strata plus placebo yielded more clinically relevant groupings while preserving statistical power for the ANOVA. Hence, the analysis reported here is of seven groups: six valproate serum level ranges (≤55.0 μg/ml [N=35], 55.1–71.3 μg/ml [N=32], 71.4–85.0 μg/ml [N=36], 85.1–94.0 μg/ml [N=34], 94.1–107.0 μg/ml [N=33], and >107.0 μg/ml [N=33]) and placebo (N=171).

Statistical Analyses

The most conservative test of linearity includes the placebo group in the linear model. Consequently, effect size was calculated for the placebo group and each valproate serum level group by dividing the change from baseline to endpoint for each group by the standard deviation for change in that group. This effect size was then used to test the linearity of response as a function of serum valproate concentration using both parametric (linear regression) and nonparametric (Jonckheere-Terpstra) techniques, both with and without placebo in the model. One-way ANOVAs were used to compare each range with placebo and with the lowest serum valproate group on efficacy. For all analyses, alpha was set at ≤0.05.

Results

The regression analysis yielded a significant test for linearity whether placebo was included (slope: p<0.001, fitness: 0.873, Jonckheere-Terpstra technique: p<0.001) or not (slope: p<0.01, fitness: 0.757, Jonckheere-Terpstra technique: p<0.05). These results suggest a general tendency for efficacy to be greater with increasing serum levels of valproate.

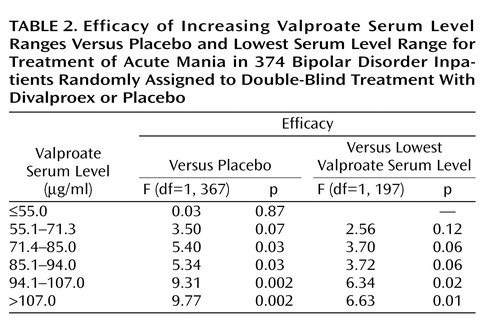

In the ANOVA that compared the five higher valproate serum levels with placebo and the lowest serum level group, efficacy was significantly greater than placebo (p<0.05) beginning at the 71.4–85.0 μg/ml range and for all higher valproate levels. In addition, the 94.1–107.0 and >107.0 μg/ml groups were superior to the lowest valproate group, ≤55.0 μg/ml (median=41 μg/ml). Table 2 illustrates the results of the ANOVA comparisons. Blood levels in the lower ranges were 60% more effective than placebo, and blood levels in the higher ranges were 120% more effective than placebo. Figure 1 illustrates effect size as a function of serum level.

The best effect associated with the highest levels of valproate was 1.06, a large effect equivalent to a change of approximately 12 points on the Young Mania Rating Scale. Adjusting this response for placebo response, as is often reported, yields an effect size for the highest levels of valproate of 0.59. Subjects in any group obtaining this effect (N=84) were examined and found to have a mean serum level of 87.5 μg/ml.

The mean discontinuation rate for an adverse event across all groups was 3%, with either no discontinuations or one discontinuation at each level. For example, the group with blood levels of 107 or greater (range=107–180 μg/ml, median=121.3) had one discontinuation due to an adverse event. Fisher’s exact test comparing each group to placebo and the two lowest valproate groups revealed no statistically significant differences in premature discontinuation.

Discussion

Evidence from the present study converges to suggest that higher valproate levels are associated with greater efficacy in the treatment of acute mania. Regression analysis supports a general linear relationship between serum valproate levels and efficacy across the groups defined in this study. Furthermore, ANOVA confirms that higher serum levels of valproate were associated with greater efficacy than the lowest valproate serum level (≤55 μg/ml). These results are consistent with previous findings that suggested a relationship between higher serum valproate levels and greater efficacy in patients with acute mania (5–9). These results were obtained despite the fact that the underlying studies were flexibly dosed, which tends to obscure dose/response relationships. With flexible dosing, nonresponders may receive the highest doses. The use of serum concentration rather than dose and results of the final evaluation rather than earlier time points should mitigate differences attributable to formulation, dose, and titration strategy that were the focus of Hirschfeld et al. (8).

The use of effect sizes to interpret treatment differences in treatment studies of mania has been advocated by Bowden et al. (10). Effect sizes, unlike Fisherian statistics, permit the investigator to evaluate the magnitude and clinical relevance of changes due to treatment. Cohen (11) suggested that an effect size of 0.2 be defined as small, 0.5 as medium, and 0.8 as large. The placebo-adjusted effect size associated with the highest levels of serum valproate in the present study was 0.59 and is higher than previous effect sizes reported in studies of valproate treatment for acute mania (2). This effect may have been constrained by a ceiling effect related to the maximum allowed serum concentration in these trials (125 μg/ml).

The present findings may be useful in guiding clinicians as to the best level of serum valproate to be employed in treatment of acute mania. Optimal doses of valproate may not be achieved until reaching serum levels of 94 μg/ml or above. Furthermore, the data suggest that tolerability is similar at higher levels in acute mania.

Goldberg et al. (6) reported that among the 10 predictive variables they examined, only time to therapeutic serum level was a significant predictor of time to remission from acute mixed or pure mania. This finding has emphasized the importance of identifying an optimal serum level and rapidly achieving that level in acute mania. Several studies (8, 12–15) have shown that valproate can be safely administered in loading doses of 20 to 30 mg/kg per day. Hirschfeld et al. (8) found that patients receiving valproate loading doses who achieved serum levels above 80 μg/ml had significantly greater improvement on days 3 and 5 than patients receiving usual titration. This finding is consistent with our data, suggesting a value in the mid-90 μg/ml range may be the optimal serum valproate level when treating acute mania. Together, these findings suggest that the rapid stabilization of acute mania may best be achieved with a loading strategy that quickly reaches a serum level at the upper end of the previously described therapeutic range. Our data, together with those of Hirschfeld et al. (8), also suggest that this strategy is well tolerated in the majority of patients.

Several limitations to the present study should be noted. Since this report utilizes a pooled analysis of three data sets, it is subject to the limitations of including data from different populations studied at different times. Furthermore, the results of this study are limited to the acute treatment period examined in this analysis. No conclusions can be drawn regarding the relationship between serum valproate levels and efficacy of treatment beyond this period. Blood levels for depression and maintenance treatment with divalproex require further study. Additionally, caution should be used in comparing effect sizes resulting from stratification by blood level to effect sizes derived from entire samples without stratification. Finally, although we found no tolerability differences based on discontinuations, the dose-related nature of some side effects is well established (16).

|

|

Presented in part at the 157th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, May 1–6, 2004. Received June 28, 2004; revision received Nov. 24, 2004; accepted Jan. 24, 2005. From the University of Colorado School of Medicine; the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Ill.; and the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Allen, University of Colorado School of Medicine, 4200 East 9th Ave., Box A011-95, Denver, CO 80220; [email protected] (e-mail).Study sponsored by Abbott Laboratories.

Figure 1. Effect Size as a Function of Valproate Serum Level for 374 Bipolar Disorder Inpatients in a Manic Episode Randomly Assigned to Double-Blind Treatment With Divalproex or Placebo

1. Pope HG Jr, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Hudson JI: Valproate in the treatment of acute mania: a placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:62–68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM, Rush AJ, Small JG, et al (Depakote Mania Study Group): Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 1994; 271:918–924; correction, 271:1830Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(April suppl)Google Scholar

4. Sachs GS, Printz DJ, Kahn DA, Carpenter D, Docherty JP: The expert consensus guideline series: medication treatment of bipolar disorder. Postgraduate Med, April 2000, pp 1-104Google Scholar

5. Vasudev K, Goswami U, Kohli K: Carbamazepine and valproate: feasibility, relative safety and efficacy, and therapeutic drug monitoring in manic disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000; 150:15–23Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Goldberg JF, Garno JL, Leon AC, Kocsis JH, Portera L: Rapid titration of mood stabilizers predicts remission from mixed or pure mania in bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:151–158; correction, 59:320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. McCoy L, Votolato NA, Schwarzkopf SB, Nasrallah HA: Clinical correlates of valproate augmentation in refractory bipolar disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1993; 5:29–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hirschfeld RMA, Baker JD, Wozniak P, Tracy K, Sommerville KW: The early efficacy and safety of oral loaded divalproex sodium in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:841–846Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Niedermier JA, Nasrallah HA: Clinical correlates of response to valproate in geriatric inpatients. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1998; 10:165–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bowden CL, Davis J, Morris D, Swann A, Calabrese J, Lambert M, Goodnick P: Effect size of efficacy measures comparing divalproex, lithium and placebo in acute mania. Depress Anxiety 1997; 6:26–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

12. Hirschfeld RMA, Keck PE, Allen MH, McEvoy J, Fawcett J, Nemeroff CB, Russell J, Bowden CL: Safety and tolerability of oral loading divalproex in acutely manic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:815–818Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Tugrul KC, Bennett JA: Valproate as a loading treatment in acute mania. Neuropsychobiology 1993; 27:146–149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Tugrul KC, Bennett JA: Valproate oral loading in the treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:305–308Medline, Google Scholar

15. Martinez JM, Russell JM, Hirschfeld RM: Tolerability of oral loading of divalproex sodium in the treatment of acute mania. Depress Anxiety 1998; 7:83–86Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Beydoun A, Sackellares JC, Shu V (Depakote Monotherapy for Partial Seizures Study Group): Safety and efficacy of divalproex sodium monotherapy in partial epilepsy: a double-blind, concentration-response design clinical trial. Neurology 1997; 48:182–188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar