Psychiatric Comorbidity in Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Findings From Multiplex Families

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity were assessed in adults with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) identified through a genetic study of families containing multiple children with ADHD. METHOD: Lifetime ADHD and comorbid psychopathology were assessed in 435 parents of children with ADHD. Rates and mean ages at onset of comorbid psychopathology were compared in parents with lifetime ADHD, parents with persistent ADHD, and those without ADHD. Age-adjusted rates of comorbidity were compared with Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Logistic regression was used to assess additional risk factors for conditions more frequent in ADHD subjects. RESULTS: The parents with ADHD were significantly more likely to be unskilled workers and less likely to have a college degree. ADHD subjects had more lifetime psychopathology; 87% had at least one and 56% had at least two other psychiatric disorders, compared with 64% and 27%, respectively, in non-ADHD subjects. ADHD was associated with greater disruptive behavior, substance use, and mood and anxiety disorders and with earlier onset of major depression, dysthymia, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. Group differences based on Kaplan-Meier age-corrected risks were consistent with those for raw frequency distributions. Male sex added risk for disruptive behavior disorders. Female sex and oppositional defiant disorder contributed to risk for depression and anxiety. ADHD was not a significant risk factor for substance use disorders when male sex, disruptive behavior disorders, and socioeconomic status were controlled. CONCLUSIONS: Adult ADHD is associated with significant lifetime psychiatric comorbidity that is not explained by clinical referral bias.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a highly heritable neurodevelopmental syndrome with significant lifetime risk for functional impairment (1). Coexisting psychopathology is common (2), and the potential clinical importance of comorbidity has been recognized in children (3). Our understanding of psychiatric comorbidity in adult ADHD is based on a limited number of reports. Changes in ADHD nosology, increased awareness of ADHD persistence, and differing diagnostic approaches to adults further confound our appreciation of the relationship between adult ADHD and other disorders. In this current report we examine ADHD and comorbid psychopathology in a group of adults ascertained through pairs of siblings with ADHD.

Several longitudinal studies initially informed our understanding of lifetime psychopathology in hyperactive children. From an original group of 101 hyperkinetic boys compared with nonhyperactive comparison subjects, investigators described higher rates of conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and nonalcoholic substance use disorders in the probands at early adult follow-up than in the comparison subjects (4). Marijuana and cocaine were the most frequently used recreational drugs, and initiation of substance abuse was generally subsequent to conduct disorder. Mood and anxiety disorders were rare; however, the subjects had not fully passed through the risk periods for these conditions. Additionally, subjects were excluded if the primary reason for referral was aggression. A second cohort of hyperkinetic children showed significantly more antisocial personality disorder and somewhat higher rates of alcohol and marijuana use in early adulthood than did comparison subjects (5). These studies might have underestimated some comorbidities because of the lack of follow-up for some subjects. However, higher rates of antisocial behavior and substance use disorders emerge as consistent findings in virtually all studies of comorbidity and adult ADHD.

A more complicated picture has been described in patients diagnosed with ADHD as adults. Shekim and colleagues (6) assessed 51 clinically referred ADHD adults and found high rates of lifetime comorbidity, including 51% for generalized anxiety disorder, 34% for alcohol abuse or dependence, 34% for other drug abuse or dependence, 25% for dysthymia, 18% for separation anxiety disorder, 13% for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and 10% for major depressive disorder. Downey and colleagues (7) described psychological profiles for 78 clinically referred ADHD adults and reported that 37% evidenced current depression, 33% had alcohol abuse or dependence, 22% had other drug abuse or dependence, and 13% had antisocial personality. These studies were uncontrolled and based on groups of treatment-seeking patients.

Biederman and colleagues (8) studied 84 clinic-referred ADHD adults, 36 nonreferred ADHD adults, and 207 adults without ADHD. The ADHD groups demonstrated higher rates of oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, depression, substance abuse/dependence, and anxiety. Subsequent reports described a higher risk for psychoactive substance use disorders, particularly among men and subjects in lower socioeconomic classes (9). The ADHD individuals had earlier onsets of substance use disorders than did the comparison subjects (10, 11). Murphy and Barkley (12), in a study of 172 clinically referred ADHD adults and 30 comparison subjects, noted higher rates of alcohol abuse or dependence (35% versus 10%), drug abuse or dependence (14% versus 3%), oppositional defiant disorder (30% versus 7%), and conduct disorder (17% versus 0%) in the patients with ADHD. The ADHD group also exhibited high rates of comorbid anxiety disorders (32%), major depressive disorder (18%), and dysthymia (32%), although these were not significantly higher than the rates for the comparison subjects.

Several studies have examined differences in psychiatric comorbidity across ADHD subtypes. One study, using proxy DSM-IV subtypes in 149 adults diagnosed according to DSM-III-R, found higher rates of oppositional defiant disorder, bipolar disorder, and substance use disorders in patients with the combined subtype than in those with other subtypes and higher rates of oppositional defiant disorder, OCD, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the hyperactive-impulsive subtype than in the inattentive subtype (13). A second study (14) found that subjects with the combined or hyperactive-impulsive subtype had a higher rate of oppositional defiant disorder than did subjects with the inattentive subtype, with no subtype difference in conduct disorder, depression, or anxiety.

While existing evidence suggests that there is a significant risk of lifetime psychiatric comorbidity in adult ADHD, the design features of previously reported studies limit the generalizability of the findings. Studies based on DSM-III-R criteria might underrecognize comorbidity with the predominately inattentive subtype. Older studies of hyperactive children emphasized male subjects and might not represent clinical phenomenology in female subjects. In comparisons of comorbidity across ADHD subtypes, classification has been based on adult presentations, which do not reflect changes in symptom pattern over time. Finally, most published studies have been based on clinical study groups, which might bias the reported rates of psychopathology.

The UCLA ADHD Genetic Study examined adult ADHD and comorbid psychopathology in a large, nonclinical study group. Families were recruited on the basis of having two or more affected siblings with ADHD. Parents of these affected sibling pairs underwent comprehensive assessment to identify lifetime psychopathology and ADHD versus non-ADHD status. We explored several specific hypotheses, namely, 1) that findings in ADHD adults identified through multiplex families would be similar to those for clinical groups described in the literature, specifically, that subjects with ADHD would have higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity; 2) that ADHD subjects would evidence earlier ages at onset for comorbid conditions; 3) that differences in comorbidity would occur across ADHD subtypes; and 4) that other, non-ADHD factors would contribute additional risk for psychopathology.

Method

Study Group

The subjects in this study were 435 parents of ADHD children ascertained through 230 families recruited by sampling of affected sibling pairs. The procedures for family recruitment, screening, and child assessment are detailed in a previous publication (15). All families spoke English and had biological parents available to participate. Families were included if at least one child met the full DSM-IV ADHD criteria and another child had a diagnosis of definite or probable ADHD. Probable ADHD was defined as a subject falling one symptom or criterion short of a full diagnosis (including behavioral symptoms, onset by age 7, duration of 6 months, or presence in two settings) but having evidence of impairment. Subject characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean socioeconomic status rank as defined by Hollingshead (16) was 2.3 (SD=0.9) (Hollingshead range=I–V).

Instruments and Procedures

After receiving a full oral explanation of all study requirements and procedures, the parents and children provided written statements of informed consent/assent approved by the UCLA institutional review board. Each adult parent completed the Wender Utah Rating Scale as a self-report of childhood ADHD symptoms (17) and an ADHD Rating Scale-IV (18) as a self-report of current ADHD symptoms, as well as an ADHD Rating Scale-IV for current ADHD symptoms in the spouse. Clinical psychologists or highly trained interviewers with extensive experience and reliability training conducted the adult interviews. We determined lifetime history of psychopathology with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version Modified for the Study of Anxiety Disorders (SADS-LA), a highly reliable semistructured diagnostic instrument for DSM-IV disorders (19). The SADS-LA was supplemented with the behavioral disorders section of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) (20) to elucidate lifetime and persistent diagnoses of ADHD, as previously described (8). The K-SADS-PL was also used to elucidate retrospective diagnoses of childhood oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Our criteria for designation of lifetime and persistent ADHD are summarized in Table 2. Subjects who did not meet the criteria for lifetime ADHD constituted the non-ADHD group. Classification of the lifetime ADHD subtype was based on childhood symptoms between the ages of 5 and 12 years. Classification of persistent ADHD was based on current adult symptoms.

“Best-estimate” diagnoses were assigned after review of all available clinical information, including semistructured interviews, behavioral ratings, and evidence of impairment, with senior clinicians (J.J.M., J.T.M., D.E.L.). All interviews were videotaped, and a subset was rerated independently by senior clinicians to maintain ongoing reliability. The mean weighted kappa based on 24 rerated adult tapes was 0.88 (SD=0.10), with weighted kappa values of 0.91, 0.86, and 0.83 for ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder, respectively (15). The mean kappa value computed for the agreement between the initial rater and the best-estimate diagnoses for 10 major psychiatric diagnoses occurring in more than 5% of all subjects in the current study group was 0.95 (SD=0.03).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were summarized. ADHD status was based on the criteria for either a probable or definite diagnosis. Diagnosis of other psychiatric conditions required DSM-IV criteria. We used t tests or chi-square analyses to determine differences in demographic information between groups. Statistically significant differences in demographic variables were assessed at an alpha level of <0.05. The mean ages of the group with lifetime ADHD, the group with persistent ADHD, and the unaffected group were compared with t tests to assess the need to age correct rates of comorbidity.

Comorbidity frequencies were calculated for the lifetime ADHD, persistent ADHD, and unaffected groups, and each ADHD group was compared with the unaffected group by means of chi-square analyses. Additional t test comparisons of the mean ages at onset for comorbid disorders were made when at least five subjects were available in both the ADHD and non-ADHD groups. Within the groups having lifetime and persistent ADHD, we also assessed potential differences in comorbid conditions between DSM-IV subtypes.

To estimate age-corrected rates of comorbidity (morbidity risks) in the ADHD and non-ADHD parents, we used the Kaplan-Meier estimate from survival analysis in which age at onset was the survival time for affected individuals and age at the time of interview was the time of censoring for individuals with the comorbid disorder. Log rank chi-square tests were used to compare the lifetime rates of the comorbid disorders in each group, adjusted for age. In the case of classifications with multiple disorders (e.g., multiple anxiety disorders), the earliest onset was included in the analysis.

We applied stepwise logistic regression in which the model freely entered variables at a significance level of 0.05 on the basis of optimal fit to identify additional risk factors for conditions associated with ADHD in univariate tests. The category “disruptive behavior disorders” included all subjects with oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder. Potential predictors of disruptive behavior disorders included lifetime ADHD, age, sex, socioeconomic status, race, and interaction terms. Potential predictors for all other disorders included ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, age, sex, socioeconomic status, race, and interaction terms. Goodness of fit for the derived models was assessed with Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-square, concordance, and R2 statistics.

In consideration of the multiple tests, we applied the Bonferroni correction by dividing 0.05 by the number of comparisons within each set of analyses to determine the alpha level for statistical significance and to avoid type I error. For comparisons of comorbidity, significance was assessed at an alpha level of <0.005. For comparisons of ages at onset, significance was assessed at an alpha of <0.01. We noted nearly significant differences, when p values were less than 0.05 and greater than the derived alpha values, to avoid type II error. All statistical tests were performed by using SAS 8.2 (21).

Results

Family and parental ADHD status is summarized in Table 3. The modal numbers of childhood inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms endorsed by ADHD parents were eight and six, respectively, compared with zero and zero in non-ADHD parents. The lifetime ADHD group comprised 35% of the subjects (N=152). Of the parents with lifetime ADHD, 53% (N=81) had the inattentive subtype and 47% (N=71) had the hyperactive/impulsive subtype or combined subtype, and there was no difference by sex (χ2=1.8, df=1, p=0.17). The remaining 65% of the subjects (N=283) were unaffected.

Of the 230 families, 100 (43%) had no parent with ADHD, 108 (47%) had one affected parent, and 22 (10%) had two affected parents; these rates are not different from those expected under random mating (χ2=0.9, df=1, p=0.33). ADHD parents were more likely to be Caucasian (χ2=6.4, df=1, p=0.01), unskilled workers (χ2=16.6, df=7, p=0.02), and without a college degree (χ2=5.5, df=1, p=0.02). There were no group differences by sex (χ2=0.1, df=1, p=0.73) or marital status (χ2=1.6, df=2, p=0.20). There were no significant differences in mean age between the groups with lifetime, persistent, and no ADHD (Table 4).

The ADHD parents had more lifetime psychopathology, with 87% having at least one and 56% at least two other psychiatric disorders, compared with 64% and 27%, respectively, in the non-ADHD subjects (χ2=63.3, df=5, p<0.0001). Table 5 compares the raw frequencies of comorbid psychiatric conditions in the parents with lifetime ADHD and those without ADHD. Given that single anxiety disorders are common, we examined a threshold of two or more anxiety disorders to minimize overdiagnosis, as suggested by others (8). Anxiety disorders included separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, simple phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and PTSD. Substance abuse and substance dependence were considered together as substance use disorders. The subjects with lifetime ADHD showed significantly higher rates of major depressive disorder, multiple anxiety disorders, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and substance use disorders. A nonsignificantly higher rate of bipolar I disorder was detected, but the analysis was limited by the relatively low number of bipolar subjects.

The numbers of subjects were sufficient to compare the mean ages at onset for five comorbid conditions. The ADHD subjects had earlier onsets of oppositional defiant disorder (mean age=7.6 years, SD=3.0) than did the subjects without ADHD (mean=10.6 years, SD=3.0) (t=3.12, df=45, p=0.003) and major depressive disorder (mean age=24.7 years, SD=10.4, versus mean=29.0, SD=9.9) (t=2.82, df=194, p=0.005). Nearly significant differences in onset age were noted for dysthymia (mean=21.5 years, SD=10.7, versus mean=29.8 years, SD=13.2) (t=2.43, df=51, p=0.02) and conduct disorder (mean age=10.2, SD=3.0, versus mean=12.2, SD=2.3) (t=2.22, df=38, p=0.03). There was no difference in age at onset for substance use disorders between the parents with lifetime ADHD (mean=18.3 years, SD=5.0) and the parents without ADHD (mean=18.4, SD=6.1) (t=0.06, df=86, p=0.95).

Assessment of comorbidity across subtypes of lifetime ADHD revealed a higher rate of oppositional defiant disorder in the group with hyperactive/impulsive or combined symptoms (25%) than in the group with the inattentive subtype (9%) (χ2=7.7, df=1, p=0.006). No other differences were evident.

Persistent ADHD was diagnosed in 79 (52%) of the 152 subjects with lifetime ADHD. Their patterns of comorbidity were similar to those in the group with lifetime ADHD, and the rates of comorbid disorders were significantly higher than the rates for non-ADHD parents. Among the subjects with persistent cases, 63% evidenced major depressive disorder (χ2=13.2, df=1, p=0.0003), 25% had multiple anxiety disorders (χ2=17.4, df=1, p<0.0001), 18% had oppositional defiant disorder (χ2=31.6, df=1, p<0.0001), 18% had conduct disorder (χ2=15.4, df=1, p<0.0001), and 47% had substance use disorders (χ2=10.6, df=1, p=0.001). Bipolar I disorder was significantly more common than in the unaffected subjects (p=0.009, Fisher’s exact test), despite a low overall frequency of bipolar disorder (four out of 79 parents with persistent ADHD and one of 283 non-ADHD parents). Subjects with the hyperactive/impulsive or combined subtype exhibited a higher rate of substance use disorders than those with the inattentive subtype (69% versus 34%) (χ2=9.0, df=1, p=0.003), and there were nonsignificantly higher rates of oppositional defiant disorder (31% versus 10%) (χ2=5.6, df=1, p=0.02) and conduct disorder (31% versus 10%) (χ2=5.6, df=1, p=0.02).

The group differences in the frequencies of comorbid disorders according to Kaplan-Meier age-corrected risks were consistent with those presented for the raw frequency distributions. The morbid risks for the parents with lifetime ADHD versus non-ADHD parents were 16.5% (SE=3.1%) versus 3.9% (SE=1.2%) for conduct disorder, 72.7% (SE=8.6%) versus 44.5% (SE=3.3%) for major depressive disorder, 17.5% (SE=3.2%) versus 8.3% (SE=1.9%) for multiple anxiety disorders, 56.6% (SE=8.1%) versus 32.9% (SE=4.2%) for substance use disorders, and 28.0% (SE=10.1%) versus 1.1% (SE=0.6%) for oppositional defiant disorder. A similar pattern was evident for the risks of the parents with persistent ADHD versus those of the non-ADHD subjects for conduct disorder (mean=13.4%, SE=3.9%, versus mean=3.9%, SE=1.2%), major depressive disorder (mean=78.2%, SE=7.8%, versus mean=44.5%, SE=3.3%), multiple anxiety disorders (mean=19.7%, SE=4.8%, versus mean=8.3%, SE=1.9%), substance use disorders (mean=44.9%, SE=5.7%, versus mean=32.9%, SE=4.2%), and oppositional defiant disorder (mean=30.9%, SE=12.7%, versus mean=1.1%, SE=0.6%). All differences in age-corrected rates were significant at p<0.005.

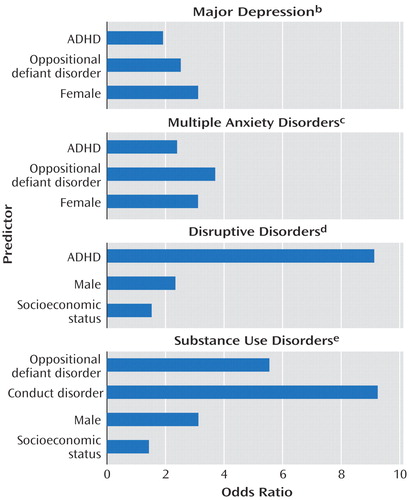

Odds ratios and goodness-of-fit tests from logistic regression models for four comorbid disorders associated with lifetime ADHD appear in Figure 1. Disruptive disorders were strongly influenced by ADHD and male sex. For major depression, substance use disorders, and multiple anxiety disorders, oppositional defiant disorder invariably played a greater role than ADHD; conduct disorder played the largest role in substance use disorders. ADHD was not a significant risk factor for substance use disorders when male sex, disruptive behavior disorders, and socioeconomic status were controlled. Sex differences emerged, with women demonstrating greater risks for mood and anxiety disorders and men having a higher risk for substance use disorders, independent of ADHD status. Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-square tests indicated that the observed data were not significantly different from expected values derived from each model (p>0.05). Most models had good estimation of predicted variables (concordance>0.70).

Discussion

This study confirms and expands previous findings of greater risk for comorbid psychopathology in adult ADHD. Like others, we demonstrated lower educational and occupational achievement in adults with ADHD (8, 12). Results from this current study are particularly noteworthy, given the large number of subjects, inclusion of an unaffected comparison group, and nonclinical ascertainment. The higher rates of comorbidity in adult ADHD do not appear to result from clinical referral bias or recruitment from tertiary care populations.

The patterns of comorbidity confirm findings in earlier studies, with high rates of lifetime depression, anxiety, disruptive behaviors, and substance use disorders. Higher risk for disruptive behavior disorders was predicted by ADHD and male sex, as noted by others (13). Also consistent with other reports (4, 5, 8, 13) was the fact that risk for substance use disorders was mediated by disruptive behavior disorders, male sex, and lower socioeconomic status, without an apparent direct effect from ADHD. The relationship between adult ADHD and internalizing disorders is less clear. The higher rate of major depressive disorder seen in the current study is consistent with some clinical findings (8) but not others (12). ADHD contributed significant risk for major depressive disorder but less than that conferred by female sex and oppositional defiant disorder. Similarly, although ADHD and multiple anxiety disorders were associated on univariate tests, female sex and oppositional defiant disorder conferred more risk than ADHD on logistic regression. The R2 vales for each logistic regression model suggest that other unmeasured variables contribute substantial additional risk for each condition. Overall, the patterns of comorbidity in this subject group confirm that ADHD is a general risk factor for mood and anxiety disorders as well as disruptive behavior. The mechanisms by which lifetime ADHD increases risk for emotional disorders remains to be determined.

In this study we considered both lifetime and persistent ADHD status. Persistent ADHD is an arbitrary construct. Persistence is defined by symptom thresholds developed for children that have never been validated in adults. Some have noted that ADHD persistence is a matter of syndromal definition and not continued dysfunction (22), while others have suggested that lower symptom thresholds more appropriately define groups of clinically impaired adults (12, 23). Approximately 50% of our subjects with retrospectively determined childhood ADHD continued to evidence full persistence, a finding similar to that in longitudinal investigations of children with ADHD who were followed into young adulthood (23). We found no differences in patterns of comorbidity between the lifetime and persistent ADHD groups. The strength of the association between ADHD and bipolar I disorder, however, was more evident in the persistent cases. This suggests that bipolar disorder more frequently occurs with more severe forms of ADHD. While the 5% rate of bipolar I disorder in the group with persistent ADHD is lower than that described in clinical studies (24), it is significantly higher than seen in the general population.

The ADHD subjects demonstrated earlier onsets for major depressive disorder, dysthymia, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. Although recalled retrospectively, the mean ages at onset for oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder are consistent with descriptions of earlier onset of disruptive behavior disorders in ADHD-affected youth (25). The mean ages at onset for major depressive disorder and dysthymia, however, do not extend to childhood, suggesting that these disorders are not continuations of pediatric psychopathology. Nonetheless, it appears that ADHD subjects are vulnerable to earlier development of adult depressive disorders. In contrast to other authors (9–11), we did not confirm a lower age at onset for substance use disorders, although the rates of substance use disorders were higher than that for the unaffected subjects.

A higher rate of oppositional defiant disorder in both lifetime and persistent cases of the combined ADHD subtype is consistent with findings in previous studies (13, 14). Among subjects with persistent ADHD, the results are consistent with the hypothesis that individuals with the combined subtype show greater conduct disorder and substance use disorders and inattentive individuals show more internalizing disorders (14). Hyperactive/impulsive symptoms decrease over time (22). Adults meeting the full threshold for the combined subtype might represent the most severe cases of childhood ADHD and be at particular risk for impulse control difficulties. Differences found in the persistent inattentive subtype are more difficult to interpret. Adults currently diagnosed as having the inattentive subtype might have no history of hyperactive/impulsive difficulties or, alternatively, be one hyperactive/impulsive symptom short of the combined subtype. It is noteworthy that more significant differences in psychopathology were evident among subjects with persistent cases. Additional research identifying key differences in processes underlying the two main dimensions of ADHD are needed.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date of psychiatric comorbidity and adult ADHD in a nonclinical study group. There are several advantages to its design. Adults were identified through a study of multiply affected ADHD siblings. As such, the subjects are likely to represent more genetic cases of ADHD (26). Although not independent, comparison of ADHD cases with unaffected parents inherently controls subjects for age and socioeconomic status and minimizes group differences due to recall bias. This study had several limitations. Parents might have more readily endorsed ADHD symptoms in light of having affected children. However, other studies that have examined this possibility found no evidence suggesting reporter bias (27, 28). Families were recruited only if both biological parents were available. Participating adults were therefore more likely to be associated with intact families. Families with the most dysfunctional parents would be ineligible to participate, and the rates of reported comorbid psychopathology might underestimate the true incidence of psychopathology. The diagnoses were retrospective. Although retrospective assessment of adult ADHD has proven valid in clinical, family, neurobiological, and outcome studies (29), different results might emerge from a prospective study of DSM-diagnosed ADHD children. Finally, while using unaffected parents as comparison subjects had advantages, the study did not control for other factors that might affect rates of comorbidity. For example, the rates of major depressive disorder for ADHD and non-ADHD subjects were significantly higher than in the general population. Our study did not assess the relationship between raising multiple ADHD children and development of parental psychopathology.

This study has implications for clinical practice and research. High rates of psychiatric comorbidity in the estimated 4% of adults with ADHD are a major public health concern (1). Parents of ADHD children have a greater risk not only for ADHD but for other emotional disorders that might adversely affect parenting. Ongoing efforts in clinical education must emphasize consideration of comorbid psychopathology in assessment of adult ADHD, as well as consideration of ADHD in the evaluation of other psychiatric disorders, such as depression or anxiety. Further research is required to determine if increased psychopathology results from independent biological susceptibilities associated with ADHD, if comorbid psychopathology emerges as a developmental consequence of ADHD, and if continuous treatment of ADHD reduces adult comorbidity. Longitudinal studies of children with DSM-diagnosed ADHD are necessary to determine true rates of comorbid psychopathology in unbiased subject groups. Research is also warranted to identify potential interventions that decrease the risk for comorbidity in ADHD and to provide the empirical data necessary to support clinical treatment of complicated cases.

|

|

|

|

|

Received March 21, 2003; revisions received Jan. 30 and June 21, 2004; accepted Sept. 13, 2004. From the Center for Neurobehavioral Genetics and the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, Neuropsychiatric Institute and David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. McGough, Suite 1414, 300 UCLA Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH awards MH-01966 (to Dr. McGough), MH-63706 (to Dr. Smalley), and MH-10805 (to Dr. McCracken).

Figure 1. Predictorsa of Four Comorbid Disorders in Parents With Lifetime ADHD in Families Containing Multiple Siblings With ADHD

aFrom logistic regression.

bNot significantly different from expected values derived from model (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2=1.2, df=3, p=0.75). Adjusted R2=0.14. Concordance=0.68.

cNot significantly different from expected values derived from model (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2=4.0, df=3, p=0.26). Adjusted R2=0.15. Concordance=0.73.

dNot significantly different from expected values derived from model (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2=1.7, df=7, p=0.97). Adjusted R2=0.27. Concordance=0.80.

eNot significantly different from expected values derived from model (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2=6.0, df=6, p=0.42). Adjusted R2=0.26. Concordance=0.75.

1. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Spencer TJ: Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Annu Rev Med 2002; 53:113–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Jensen P, Martin D, Cantwell DP: Comorbidity in ADHD: implications for research, practice, and DSM-V. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1065–1079Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. American Academy of Pediatrics: Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and evaluation of the child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 2000; 105:1158–1170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M: Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:565–576Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hechtman L, Weiss G: Controlled prospective fifteen year follow-up of hyperactives as adults: non-medical drug and alcohol use and anti-social behaviour. Can J Psychiatry 1986; 31:557–567Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Shekim W, Asarnow RF, Hess E, Zaucha K, Wheeler N: A clinical and demographic profile of a sample of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, residual state. Compr Psychiatry 1990; 31:416–425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Downey KK, Stelson FW, Pomerleau OF, Giordani B: Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: psychological test profiles in a clinical population. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:32–38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, Wilens T, Norman D, Lapey KA, Mick E, Lehman BK, Doyle A: Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity, cognition, and psychosocial functioning in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1792–1798Link, Google Scholar

9. Biederman J, Wilens TE, Mick E, Faraone SV, Spencer T: Does attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder impact the developmental course of drug and alcohol abuse and dependence? Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44:269–273Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, Spencer T: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is associated with early onset substance use disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:475–482Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Mick E: Does ADHD affect the course of substance abuse? findings from a sample of adults with and without ADHD. Am J Addict 1998; 7:156–163Medline, Google Scholar

12. Murphy K, Barkley RA: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults: comorbidities and adaptive impairments. Compr Psychiatry 1996; 37:393–401Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Millstein RB, Wilens TE, Biederman J, Spencer TJ: Presenting ADHD symptoms and subtypes in clinically referred adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord 1997; 2:159–166Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Murphy KR, Barkley RA, Bush T: Young adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: subtype differences in comorbidity, educational, and clinical history. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:147–157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Smalley SL, McGough JJ, Del’Homme M, NewDelman J, Gordon E, Kim T, Liu A, McCracken JT: Familial clustering of symptoms and disruptive behaviors in multiplex families with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:1135–1143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Hollingshead AB: Two-Factor Index of Social Position. New Haven, Yale University, 1957Google Scholar

17. Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW: The Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:885–890; correction, 150:1280Link, Google Scholar

18. DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopolous AD, Reid R: ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation. New York, Guilford, 1998Google Scholar

19. Fyer AJ, Mannuzza SM, Klein DF, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version Modified for the Study of Anxiety Disorders (SADS-LA) (1985), Updated for DSM IV (SADS-LA IV). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Anxiety Family Genetics Unit, 1995Google Scholar

20. Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:980–988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. SAS Version 8.2. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2001Google Scholar

22. Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV: Age-dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: impact of remission definition and symptom type. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:816–818Link, Google Scholar

23. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K: The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2002; 111:279–289Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kiely K, Ablon JS, Faraone SV, Mundy E, Mennin D: Mania-like symptoms suggestive of childhood-onset bipolar disorder in clinically referred children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:867–876Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Moffit TE: Juvenile delinquency and attention deficit disorder: boys’ developmental trajectories from age 13 to age 15. Child Dev 1990; 61:893–910Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Smalley SL: Genetic influences in childhood-onset psychiatric disorders: autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Hum Genet 1997; 60:1276–1282Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Faraone S, Biederman J, Mick E: Symptom reports by adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: are they influenced by attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in their children? J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:583–584Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Feighner JA, Monuteaux MC: Assessing symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: which is more valid? J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:830–842Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer T, Wilens T, Seidman LJ, Mick E, Doyle AE: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: an overview. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:9–20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar