Quality Improvement for Depression in Primary Care: Do Patients With Subthreshold Depression Benefit in the Long Run?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Quality improvement programs for depression can improve outcomes, but the utility of including patients with subthreshold depression in quality improvement programs is unclear. The authors examined 57-month effects of quality improvement on clinical outcomes and mental health care utilization of primary care patients with depressive disorder and subthreshold depression. METHOD: In a group-level, randomized, controlled trial, 46 primary care clinics were randomly assigned to provide usual care or care with a quality improvement intervention that included provider training and other resources for either medication management (medications quality improvement) or evidence-based psychotherapy (therapy quality improvement). Among 1,356 enrolled depressed patients, 991 completed the 57-month follow-up interview (604 patients with depressive disorder and 387 with subthreshold depression). Outcomes measured at 57 months were presence of probable depressive disorder, unmet need for appropriate care (untreated probable disorder), and mental health care utilization in the prior 6 months. RESULTS: Among patients with subthreshold depression at baseline, those seen in clinics with quality improvement programs with special resources for therapy were less likely to have probable depressive disorder and unmet need for care at follow-up, compared with those seen in clinics that provided usual care. Among patients with depressive disorder at baseline, those seen in clinics with quality improvement programs with special resources for medication management were less likely to have unmet need for care at follow-up, compared with those seen in clinics that provided usual care. Patients with subthreshold depression at baseline seen in clinics with a quality improvement intervention were less likely at follow-up to have had a mental health visit (in primary care or specialty care, depending on the intervention) in the prior 6 months. CONCLUSIONS: Relative to usual care, quality improvement interventions improved 57-month outcomes (probable depression, unmet need, or both) for primary care patients with depressive disorder and subthreshold depression and lowered use of mental health visits for those with subthreshold depression. The results highlight the feasibility and utility of including patients with subthreshold depression in such programs.

Depressive disorders are leading causes of disability worldwide (1–4). Depression that does not meet the full diagnostic criteria (subthreshold depression) is also associated with morbidity (1, 2, 5). Quality improvement programs for depression treatment in primary care have been reported to improve health outcomes over follow-up periods of 12–28 months (6–16). Most such quality improvement programs focused on patients with depressive disorder rather than subthreshold depression (8, 9, 11–16). The value of including patients with subthreshold depression in such programs is uncertain because treatment efficacy is not well established for this group; some studies suggested benefits, and others suggested no benefits or benefits only among sicker patients (17–20). Patients with subthreshold depression have a high natural recovery rate (8), but this population may include persons with short-lived, chronic, or recurrent depressive symptoms with or without episodes of depressive disorder (21–23). However, long-term follow-up data on response to treatment or to quality improvement programs are limited.

Partners in Care is a quality improvement demonstration that enrolled 1,356 patients with depressive symptoms, nearly half of whom had subthreshold depression (24). In Partners in Care, primary care clinics were randomly assigned to provision of usual care or to provision of care with one of two quality improvement interventions that provided education and resources for medication management (medications quality improvement intervention) or evidence-based psychotherapy (therapy quality improvement intervention). The interventions were intended to facilitate appropriate depression treatment decisions while retaining providers’ and patients’ choice of treatments or no treatment. In the medications quality improvement intervention, specially trained nurses supported medication management for 6 or 12 months; in the therapy quality improvement intervention, local therapists offered cognitive behavior therapy with reduced copayments. In the first year of follow-up, analysis of pooled data for patients in the intervention clinics, compared to patients in the usual care clinics, showed that patients with both depressive disorder and subthreshold depression improved under the interventions, but those with depressive disorder improved earlier (during the first 6 months) (20). In the second year, the therapy quality improvement intervention improved outcomes in analyses that pooled data for patients with depressive disorder and patients with subthreshold depression (25).

In the study reported here, we explored 57-month effects of quality improvement on patients with subthreshold depression or depressive disorder. Outcomes measured at follow-up were the presence of probable depressive disorder, unmet need for treatment, and mental health care utilization. We recently reported that for the overall study group, there was a modest but significant benefit of quality improvement, compared to usual care at 5 years; this difference was caused primarily by large health gains for African Americans and Latinos (26).

Our hypotheses were based on the rationale that both interventions encouraged primary care providers to consider patients’ initial level of depression severity. In the therapy quality improvement intervention, clinician and client manuals were available to support a four-session therapy intervention for patients with subthreshold depression; manuals were also available for standard 12–16-session therapy for patients with depressive disorder. In addition, medication management was not recommended as an intervention for minor depression in the primary care clinician manuals or training programs available under either intervention. Thus, we thought that long-term benefits for patients with subthreshold depression would be more likely to occur with therapy quality improvement than with medications quality improvement. In addition, because we had previously found that the initial benefits of quality improvement were delayed for patients with subthreshold depression (20), we thought that these patients might have learned under the interventions to constrain utilization when they were not acutely ill; this pattern could lead to lower long-term utilization if outcomes improved. Further, the resources available under therapy quality improvement facilitated use of counseling by specialty providers, while the resources under medications quality improvement facilitated medication management within the primary care practice. Therefore, we expected that at long-term follow-up, the patients seen in the clinics with therapy quality improvement would be less likely to have primary care mental health visits, while the patients seen in the clinics with medications quality improvement would be less likely to have specialty mental health visits. We considered our hypotheses to be exploratory because there is little empirical precedent for such long-term follow-up of quality improvement interventions.

Method

Experimental Design and Implementation

Partners in Care is a group-level, randomized, controlled trial of quality improvement for depression treatment (24–29). Participating clinics and clinicians were from six managed care organizations; a total of 46 of 48 eligible primary care clinics and 181 of 183 eligible primary care clinicians participated. The clinics were matched in blocks of three on the basis of specialty mix, patient socioeconomic and demographic factors, and the on-site presence of mental health specialists. The clinics within each block were then randomly assigned to the usual care, medications quality improvement, or therapy quality improvement condition.

Study staff screened 27,332 consecutive patients over a period of 5–7 months in each practice between June 1996 and March 1997. Patients were eligible if they intended to use the clinic for 12 months and if they had positive results on a screening test for current depressive symptoms plus probable major depressive or dysthymic disorder in the last year, according to the World Health Organization’s 12-month Composite International Diagnostic Interview (30). Patients were ineligible if they were under age 18 years or not fluent in English or Spanish or if their primary care providers were not covered by their insurance. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of RAND Corp. and the participating primary care clinics.

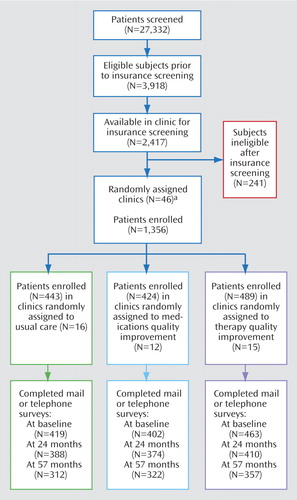

Of the patients who completed the screening, 3,918 were potentially eligible, but many left the clinic before their insurance status could be determined; 2,417 were available to confirm insurance, and 241 (10%) were ineligible after their insurance status was determined. Of 1,854 patients who read the informed consent document, 1,485 (80%) agreed to participate. Of these, 55 were not included because they were recruited during a pilot phase in which they met exclusion criteria that were later dropped, and 74 disenrolled during baseline assessment, yielding 1,356 enrolled participants (73% of those who read the informed consent document): 443 in the clinics implementing usual care, 424 in the clinics with the medications quality improvement intervention, and 489 in the clinics with the therapy quality improvement intervention (Figure 1).

Interventions

The interventions are described elsewhere (31) and at http://www.rand.org/organization/health/pic.products/order.html. We estimated each managed care organization’s participation costs, and the study provided one-half that amount. The amount provided to the managed care organizations ranged from $35,000 to $70,000. The clinics assigned to the interventions were provided with training and resources to initiate and monitor quality improvement. Patients and clinicians retained choice of treatment. The randomization involved the clinic-level resources for the care described in the following paragraphs and did not involve treatment directly.

For both interventions, local teams were trained in a 2-day workshop to educate primary care clinicians, supervise staff, and conduct program oversight. Nurses in the primary care practices were trained in patient assessment, education, and activation for treatment. The clinics were given patient education pamphlets, videotapes, tracking forms, manuals for clinicians, lecture slides, and pocket reminder cards. The materials presented psychotherapy and antidepressant medication as equally effective for most patients, encouraged attention to patients’ preferences, and advised adjustment of treatment plans to accommodate patients’ needs and preferences (32, 33).

In the medications quality improvement intervention, nurse specialists assigned by the managed care organization were available to the clinics to support medication adherence through monthly office visits or telephone contacts for 6 or 12 months after medication initiation; the duration of this support was randomized at the patient level. In the therapy quality improvement intervention, therapists affiliated with the clinic, for example, through a contract with the managed care organization or through the practice’s provider network, offered manual-based individual and group cognitive behavior therapy (34, 35) at the primary care copayment rate of about $5–$10 per visit for 6 months. All patients could have any other psychotherapy available to them but at the usual primary care copayment of about $20–$35 per visit for covered therapy services. Staff supervision was provided by local experts, who were assisted by study experts. Patients could choose treatment with medications, therapy, both, or neither. In the first and second 6 months of the study, 40% and 35%, respectively, of the patients in the clinics with therapy quality improvement received an antidepressant, and 38% and 34%, respectively, received at least four psychotherapy sessions. In the first and second 6 months of the study, 52% and 43%, respectively, of the patients in the clinics with medications quality improvement received an antidepressant, and 30% and 29%, respectively, received at least four psychotherapy sessions (20, 31).

Each clinic assigned to the quality improvement interventions was provided with a list of the participating patients and an indicator for those who met the Composite International Diagnostic Interview criteria for 12-month depressive disorder. In their study training, intervention providers were encouraged to treat all patients with a depressive disorder and to watch for signs of emerging disorder in patients with subthreshold depression. For the patients with subthreshold depression, a four-session program of cognitive behavior therapy was available in the clinics with the therapy quality improvement intervention. In the clinics with the medications quality improvement intervention, a nurse specialist was available to assist with medication management anytime within the 6- or 12-month window after the patient enrolled. Nurse specialists offered education about depression and depression treatment to intervention patients regardless of their baseline disorder status. The provider training materials noted that there was little evidence for the effectiveness of antidepressant medication for patients with subthreshold depression (32, 33). Watchful waiting was presented as one option for care of patients with subthreshold depression.

Data Collection

Patients were asked to complete the screening interview, a telephone interview that included the depressive disorders items of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview and questions about economic status, and a mailed survey at baseline. We mailed follow-up surveys every 6 months for 24 months and conducted a telephone survey at 24 months. At 57 months we conducted a telephone follow-up interview. Completion rates relative to all initial enrollees (N=1,356) were 95% for the baseline survey and 73% for the 57-month survey (N=991), representing 86% of the 1,152 participants who completed the 2-year follow-up and were still living and enrolled at the time of the 57-month follow-up. Intervention status, baseline disorder status, and their interaction were not significantly related to survey response (each p>0.10).

Measures

Intervention status

We used indicators for medications quality improvement and therapy quality improvement, each compared to usual care.

Baseline disorder status

We used data from the screening interview and the baseline Composite International Diagnostic Interview to categorize patients as having depressive disorder (i.e., 12-month major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder plus 30-day depressive symptoms) or subthreshold depression, defined as meeting the screening criteria for probable disorder but not having 12-month disorder according to the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Thirty-day symptoms were defined as 1 week or more of depressed mood and/or loss of interest in the last 30 days.

57-month outcomes

We repeated the screening measure for probable depressive disorder at follow-up, referring to the last 6 months and eliminating the dysthymic disorder item because it referred to the prior 2 years (20). The screening measure had a positive predictive value of 55%, compared with the 12-month Composite International Diagnostic Interview (24).

We developed an indicator of unmet need for depression treatment, defined as the presence of probable depressive disorder in the prior 6 months but no receipt of at least four counseling visits or 2 months of antidepressant medication (by self-report), versus having no probable disorder or receiving treatment for probable disorder (20).

The surveys included questions about primary care visits for emotional problems and specialty mental health care visits during the prior 6 months. We used various transformations to develop indicators of each type of visit and number of visits. The conclusions were similar across specifications, so we report results for the likelihood of each type of visit.

The screening interview provided data on several covariates, including age; sex; education (less than high school, completed high school, some college, completed college or more); presence of none, one, two, or more than two of 19 chronic medical conditions; ethnicity (white, Latino, African American, Asian American/Pacific Islander, or American Indian); and global mental and physical health summary scores from the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (36, 37). Using items modeled after the Health and Retirement Survey (38), we developed a household wealth variable. We used indicators for the clinic block (the matched block of clinics used for randomization).

Data Analysis

We conducted patient-level intent-to-treat analyses, maintaining subjects in their initial intervention group. As recommended for a group-level randomized trial with a moderate number of groups (39), we controlled for the effects of covariates that could affect outcomes. To test for differential effects of quality improvement by baseline disorder status, we estimated multivariate regression models with intervention status, disorder status, and their interaction as the independent variables, with adjustment for the effects of covariates. For dichotomous measures, we estimated logistic regression models. We adjusted inference statistics and standard errors for clustering of patients within clinics using a bias reduction method developed by Bell and McCaffrey (40).

The significance of comparisons by intervention status and the tests of interactions were based on regression coefficients. As recommended for group-level trials (39), degrees of freedom were based on the number of practices (43 practices had patients who provided data for the 57-month follow-up). The results are presented as standardized predictions. We used the regression parameters and each individual’s actual values for the covariates to calculate predicted outcomes, assuming the patient had been assigned to each intervention/disorder status and then averaging predictions for each group. The main analytic group included 991 patients, but the models differed in the number of patients by a few individuals because of missing data for the dependent variables.

We used multiple imputations for missing items in independent variables (41); we averaged predictions from five randomly imputed data sets and adjusted standard errors for uncertainty related to imputation (41, 42).

Nonresponse weighting was applied to the data; to facilitate generalization to the eligible subjects, each observation was weighted by the reciprocal of the probability of study enrollment and follow-up response. For sensitivity analyses, we conducted unweighted analyses without covariates, with no change in conclusions. Because the 57-month benefits of the interventions were greater among African Americans and Latinos than among whites (26), we also calculated each model separately using data for whites and for African Americans and Latinos (excluding 67 patients with other ethnic self-identification). To examine the effects of each intervention within each baseline disorder group and to test the interactions of each intervention with baseline disorder status, we applied a two-tailed significance level of 0.05. We report actual p values, which we thought appropriate for an exploratory study. We focused the main conclusions on findings for which the joint interaction test (for medications quality improvement by baseline status and for therapy quality improvement by baseline status) was significant at p<0.01. This approach balanced the desire to explore hypotheses about intervention effects for particular disorder groups and outcomes with the desire to conduct robust tests of whether there were overall differences in the effects of the interventions by disorder status.

Results

Participant Characteristics

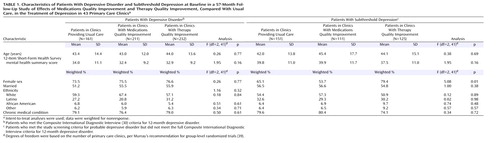

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the patients who completed the 57-month follow-up survey. The only significant difference in 18 comparisons was in the sex distribution by intervention status among patients with subthreshold depression: among patients with subthreshold depression, the percentage of female subjects was highest in the clinics with therapy quality improvement and lowest in the clinics with medications quality improvement. In combined disorder groups, the patients in the clinics with therapy quality improvement had worse mental health (as measured by the mental health summary score of the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey), although the difference only approached significance (F=2.84, df=2, 41, p=0.07). Because of these findings, sex and the mental health summary score of the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey were included in the analyses as covariates. Among patients with subthreshold depression at baseline, there was no significant difference by intervention status in the probability of having lifetime depressive disorder (F=1.27, df=2, 30, p=0.30).

Clinical Outcome

As Table 2 shows, the (adjusted) percentage of patients with baseline subthreshold depression who had probable disorder at 57-month follow-up was lower (by nearly 15 percentage points) in the clinics with therapy quality improvement than in those with usual care (t=–2.43, df=42, p=0.02), but the effect of therapy quality improvement for patients with depressive disorder was small and nonsignificant (t=0.53, df=42, p>0.10). The proportion of patients with baseline depressive disorder who had probable disorder at 57-month follow-up was lower in the clinics with medications quality improvement than in the usual care clinics, although the difference did not reach significance (t=1.92, df=42, p=0.06). However, medications quality improvement had little effect for subjects with subthreshold depression at baseline. The joint test of interaction terms was not significant at conventional levels (F=3.05, df=2, 41, p=0.06). In stratified analyses, the positive outcome effect of therapy quality improvement relative to usual care among patients with baseline subthreshold depression was qualitatively similar for each ethnic group (t=1.61–2.11, df=42, p=0.04–0.06).

Unmet Need for Depression Treatment

Patients with baseline subthreshold depression seen in the clinics with therapy quality improvement and patients with baseline depressive disorder seen in the clinics with medications quality improvement were less likely to have unmet need for depression treatment at follow-up, compared to patients with the same baseline disorder status seen in the clinics providing usual care (joint test of interactions: F=5.63, df=2, 41, p=0.007). This result suggested differential effectiveness of interventions by disorder status. Each effect represented about a 10 percentage point lower likelihood of unmet need, equivalent to 1-year findings when data were pooled for intervention groups, compared to usual care (23). The effect of therapy quality improvement among patients with baseline subthreshold depression was qualitatively similar across ethnic groups but was significant among whites (t=2.36, df=42, p=0.02); the effect of medications quality improvement among patients with baseline depressive disorder was significant among African Americans and Latinos (t=2.17, df=42, p=0.04).

Utilization

Patients with baseline subthreshold depression seen in the clinics with therapy quality improvement were less likely to have a primary care visit for mental health problems during the 6 months before the 57-month follow-up, compared with patients with baseline subthreshold depression seen in the clinics that provided usual care (t=2.24, df=42, p=0.03). A similar trend for medications quality improvement was not significant (Table 2). Although this pattern was qualitatively similar across ethnic groups, for whites the effect of medications quality improvement was significant (t=2.41, df=42, p=0.02), while for African Americans and Latinos, the effect of therapy quality improvement was significant (t=2.09, df=42, p=0.04).

Patients with baseline subthreshold depression seen in the clinics with medications quality improvement were less likely to have a specialty mental health care visit in the 6 months before the 57-month follow-up, compared with patients with baseline subthreshold depression seen in the usual care clinics, but medications quality improvement had little effect on specialty care utilization for patients with baseline depressive disorder (interaction term: t=2.98, df=42, p=0.005). Among patients seen in the clinics with therapy quality improvement, the probability of a specialty mental health visit was higher among those with baseline depressive disorder and lower among those with baseline subthreshold depression, relative to patients with the same disorder status seen in the clinics that provided usual care. Although both differences were nonsignificant, a differential effect of interventions by disorder status was suggested by the interaction term (t=2.08, df=42, p=0.04) and the joint test of interactions (F=5.02, df=2, 41, p=0.01).

Discussion

We found that therapy quality improvement improved clinical outcome at 57 months for patients with initial subthreshold depression seen in primary care clinics. Relative to usual care, both medications quality improvement and therapy quality improvement were associated with a lower likelihood of unmet need for depression treatment at follow-up; this effect was found for patients with baseline subthreshold depression seen in the clinics with therapy quality improvement and for patients with baseline depressive disorder seen in the clinics with medications quality improvement. The effects of each intervention on unmet need (8–15 percentage point differences, relative to usual care) were as large as that of the combined quality improvement interventions in the first year (20). The favorable outcome of therapy quality improvement for patients with subthreshold depression could be due to inclusion of a brief form of psychotherapy for such patients. Coupled with 1-year findings (20), these new findings reinforce the value of including patients with subthreshold depression in quality improvement programs in primary care. This finding is different from a conclusion that treatments for subthreshold depression are effective—a conclusion we cannot test with these data. For example, a study of depression treatments, relative to usual care, for elderly primary care patients found no significant health improvements for patients with initial subthreshold depression (43). In our study, the patients with subthreshold depression received education about depression and its treatment, which may have helped them make decisions about care and may have facilitated early intervention among those whose symptoms progressed to disorder. We cannot determine which specific treatments improved outcomes in the context of the interventions or generally. We previously reported, however, that across the intervention and usual care conditions, patients who had clinically appropriate care in the first 6 months, compared to those without appropriate care, had improved clinical and employment outcomes at 6-month follow-up (44).

Further, we found that patients with initial subthreshold depression in both interventions had a lower likelihood of either a primary care or a specialty mental health visit, but each intervention was associated with a lower likelihood of visits for different ethnic subgroups. The most robust findings were a lower likelihood of a specialty mental health visit across ethnic groups for patients seen in the clinics with medications quality improvement and a lower likelihood of a primary care mental health visit for whites in the clinics with therapy quality improvement and for African Americans and Latinos in the clinics with medications quality improvement. But the overall pattern suggests a lower likelihood of some kind of mental health visit over the long term for patients with initial subthreshold depression seen in the clinics with quality improvement intervention. Because the effects of quality improvement programs on use of treatments were delayed for this group (20), patients could have learned to adjust utilization to need, such as waiting for an acute episode before seeking treatment, another subject for exploration by future studies.

Our findings are subject to some important limitations. The measures were based on self-report. We recruited patients from specific, community-based managed care practices. We relied on a particular definition of subthreshold depression and used a self-report screening instrument to identify patients with this condition. Because our definition of subthreshold depression required evidence for 30-day symptoms and at least 2 weeks or more of primary mood symptoms in the last year or on most days for 2 years or more, the patients with subthreshold depression in our study may have been sicker than those with minor depression in other studies. Nevertheless, a large percentage of primary care patients (about 12%) were eligible for the study according to this definition (24).

We suggest that helping patients with subthreshold depression and their providers to understand depressive illness and treatment and to watch for early signs of depressive disorder may facilitate long-term reduction in unmet need for treatment—a goal consistent with the principles of collaborative care management for chronic disease and client-centered quality goals in medicine (45–47).

|

|

Received Nov. 12, 2003; revisions received Feb. 17 and March 22, 2004; accepted June 10, 2004. From RAND Corporation; Health Services Research Center and Center for Community Health, UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute, Los Angeles; the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences and the Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research, Department of Medicine, UCLA School of Medicine, Los Angeles; the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle; and the Department of Medicine, Department of Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Sepulveda, Calif. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Wells, RAND Corporation, 1700 Main St., P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants R10 MH-57992 and P50 MH-54623 and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant R01 HS-08349. The authors thank Maureen Carney, M.S., for coordination of follow-up, Barbara Levitan, B.A., for survey oversight, Bernadette Benjamin, M.S., for programming, the participating clinicians and patients for their time, and the following practice organizations and associated behavioral health organizations for their participation: Allina Medical Group (Twin Cities, Minn.), Patuxent Medical Group (Md.), Humana Health Care Plans (San Antonio, Tex.), MedPartners (Los Angeles), PacifiCare of Texas (San Antonio, Tex.), Valley-Wide Health Services (Colo.), Alamo Mental Health Group (San Antonio, Tex.), San Luis Valley Mental Health/Colorado Health Networks (Colo.), and Magellan/GreenSpring Behavioral Health (Md.).

Figure 1. Patient Screening and Enrollment in a 57-Month Follow-Up Study of Effects of Medications Quality Improvement and Therapy Quality Improvement, Compared With Usual Care, in the Treatment of Depression in Primary Care Clinics

aNo patients were enrolled in three of the 46 primary care clinics randomly assigned to the three study conditions.

1. Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Rogers W, Spritzer K: Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:11–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Wells KB, Sturm R, Sherbourne CD, Meredith LS: Caring for Depression. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

3. Murray CJ, Lopez AD: The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard School of Public Health (on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank), 1996Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003; 289:3095–3105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Hays RD, Rogers W, Burnam MA, Judd LL: Subthreshold depression and depressive disorder: clinical characteristics of general medical and mental health specialty outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1777–1784Link, Google Scholar

6. Thompson C, Kinmonth AL, Stevens L, Peveler RC, Stevens A, Ostler KJ, Pickering RM, Baker NG, Henson A, Preece J, Cooper D, Campbell MJ: Effects of a clinical-practice guideline and practice-based education on detection and outcome of depression in primary care: Hampshire Depression Project randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000; 355:185–191Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. King M, Davidson O, Taylor F, Haines A, Sharp D, Turner R: Effectiveness of teaching general practitioners skills in brief cognitive behaviour therapy to treat patients with depression: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2002; 324:947–950Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Walker E, Simon GE, Bush T, Robinson P, Russo J: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 1995; 273:1026–1031Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ludman E, Simon G, Walker E: A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:924–932Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Simon GE, Manning WG, Katzelnick DJ, Pearson SD, Henk HJ, Helstad CS: Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment for high utilizers of general medical care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:181–187Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hunkeler EM, Meresman JF, Hargreaves WA, Fireman B, Berman WH, Kirsch AJ, Groebe J, Hurt SW, Braden P, Getzell M, Feigenbaum PA, Peng T, Salzer M: Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9:700–708Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, Werner J, Duan N: Improving depression outcomes in community primary care practice: a randomized trial of the quEST intervention (quality Enhancement by Strategic Teaming). J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16:143–149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Von Korff M, Katon W, Bush T, Lin EH, Simon GE, Saunders K, Ludman E, Walker E, Unützer J: Treatment costs, cost offset, and cost-effectiveness of collaborative management of depression. Psychosom Med 1998; 60:143–149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Katon W, Russo J, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, Bush T, Ludman E, Walker E: Long-term effects of a collaborative care intervention in persistently depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17:741–748Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith JL, Elliott CE, Dickinson M: Managing depression as a chronic disease: a randomised trial of ongoing treatment in primary care. BMJ 2002; 325:934–937Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Liu CF, Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, Heagerty P, Felker B, Hasenberg N, Fihn S, Katon W: Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in a primary care veteran population. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54:698–704Link, Google Scholar

17. Miranda J, Muñoz R: Intervention for minor depression in primary care patients. Psychosom Med 1994; 56:136–141Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Barrett JE, Williams JW Jr, Oxman TE, Frank E, Katon W, Sullivan M, Hegel MT, Cornell JE, Sengupta AS: Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: a randomized trial in patients aged 18 to 59 years. J Fam Pract 2001; 50:405–412Medline, Google Scholar

19. Williams JW Jr, Barrett J, Oxman T, Frank E, Katon W, Sullivan M, Cornell J, Sengupta A: Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: a randomized controlled trial in older adults. JAMA 2000; 284:1519–1526Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unützer J, Miranda J, Carney MF, Rubenstein LV: Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000; 283:212–220; correction: 283:3204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Wells KB, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Hays R, Camp P: The course of depression in adult outpatients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:788–794Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS: The prevalence, clinical relevance, and public health significance of subthreshold depressions. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2002; 25:685–698Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, Endicott J, Coryell W, Paulus MP, Kunovac JL, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Rice JA, Keller MB: A prospective 12-year study of subsyndromal and syndromal depressive symptoms in unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:694–700Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Wells KB: The design of Partners in Care: evaluating the cost-effectiveness of improving care for depression in primary care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999; 34:20–29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Duan N, Miranda J, Unützer J, Jaycox L, Schoenbaum M, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV: Long-term effectiveness of disseminating quality improvement for depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:696–703Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Ettner S, Duan N, Miranda J, Unützer J, Rubenstein L: Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:378–386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Schoenbaum M, Unützer J, Sherbourne C, Duan N, Rubenstein LV, Miranda J, Meredith LS, Carney MF, Wells K: Cost-effectiveness of practice-initiated quality improvement for depression: results of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 286:1325–1330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Lagomasino I, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB: Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Serv Res 2003; 38:613–630Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Unützer J, Rubenstein L, Katon WJ, Tang L, Duan N, Lagomasino IT, Wells KB: Two-year effects of quality improvement programs on medication management for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:935–942Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 2.1. Geneva, WHO, 1995Google Scholar

31. Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unützer J, Miranda J, Minnium K, Pearson ML, Wells KB: Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999; 18:89–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Depression Guidelines Panel: Depression in Primary Care, I: Detection and Diagnosis: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Publication 93–0550. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1993Google Scholar

33. Depression Guidelines Panel: Depression in Primary Care, II: Treatment of Major Depression: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Publication 93–0551. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1993Google Scholar

34. Muñoz RJ, Miranda J: Group Therapy for Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Depression, San Francisco General Hospital Depression Clinic, 1986: Document MR01198/4. Santa Monica, Calif, RAND, 2000Google Scholar

35. Muñoz RF, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Guzman J: Manual de Terapia de Grupo para el Tratamiento Cognitivo-conductal de Depresion, Hospital General de San Franciso, Clinica de Depresion, 1986: Document MR-1198/5. Santa Monica, Calif, RAND, 2000Google Scholar

36. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30:473–483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD: SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. Boston, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1995Google Scholar

38. Smith JP: Racial and ethnic differences in wealth in the Health and Retirement Survey. J Hum Resources 1995; 30(suppl):S158-S183Google Scholar

39. Murray DM: Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

40. Bell RM, McCaffrey DF: Bias Reduction in Standard Errors for Linear Regression With Multi-Stage Samples: TD-4S9H9T. Florham Park, NJ, AT&T Labs-Research, 2002Google Scholar

41. Little RJA: Pattern-mixture models for multivariate incomplete data. J Am Stat Assoc 1993; 88:125–134Google Scholar

42. Schafer JL: Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. London, UK, Chapman & Hall, 1997Google Scholar

43. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF III, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Brown GK, McAvay GJ, Pearson JL, Alexopoulos GS: Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 291:1081–1091Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Schoenbaum M, Unützer J, McCaffrey D, Duan N, Sherbourne C, Wells KB: The effects of primary care depression treatment on patients’ clinical status and employment. Health Serv Res 2002; 37:1145–1158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH: Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127:1097–1102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M: Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 1996; 74:511–544Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2001Google Scholar