The Efficacy of Light Therapy in the Treatment of Mood Disorders: A Review and Meta-Analysis of the Evidence

Abstract

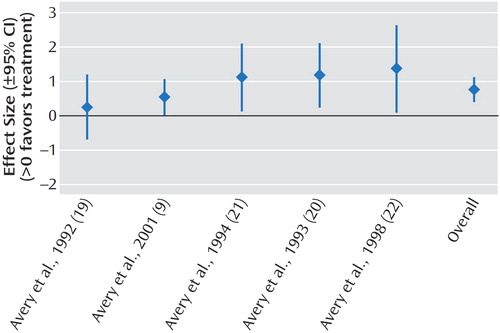

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to assess the evidence base for the efficacy of light therapy in treating mood disorders. METHOD: The authors systematically searched PubMed (January 1975 to July 2003) to identify randomized, controlled trials of light therapy for mood disorders that fulfilled predefined criteria. These articles were abstracted, and data were synthesized by disease and intervention category. RESULTS: Only 13% of the studies met the inclusion criteria. Meta-analyses revealed that a significant reduction in depression symptom severity was associated with bright light treatment (eight studies, having an effect size of 0.84 and 95% confidence interval [CI] of 0.60 to 1.08) and dawn simulation in seasonal affective disorder (five studies; effect size=0.73, 95% CI=0.37 to 1.08) and with bright light treatment in nonseasonal depression (three studies; effect size=0.53, 95% CI=0.18 to 0.89). Bright light as an adjunct to antidepressant pharmacotherapy for nonseasonal depression was not effective (five studies; effect size=–0.01, 95% CI=–0.36 to 0.34). CONCLUSIONS: Many reports of the efficacy of light therapy are not based on rigorous study designs. This analysis of randomized, controlled trials suggests that bright light treatment and dawn simulation for seasonal affective disorder and bright light for nonseasonal depression are efficacious, with effect sizes equivalent to those in most antidepressant pharmacotherapy trials. Adopting standard approaches to light therapy’s specific issues (e.g., defining parameters of active versus placebo conditions) and incorporating rigorous designs (e.g., adequate group sizes, randomized assignment) are necessary to evaluate light therapy for mood disorders.

The development of light therapy in psychiatry is closely intertwined with the original description of the syndrome of seasonal affective disorder. Two decades ago, Rosenthal and colleagues (1) described a series of patients with histories of recurrent depressions that developed in the fall or winter and spontaneously remitted during the following spring or summer. Their initial report also included preliminary findings indicating that bright artificial light, administered in a manner that would in essence extend the photoperiod, was more effective than dim light in treating seasonal affective disorder. The article presented an underlying hypothesis about the pathophysiology of the syndrome (i.e., depressogenic effects of melatonin), which in turn shaped the selection of treatment parameters: the intensity, duration, and timing of bright light exposure were designed to suppress the release of melatonin and lengthen the photoperiod.

Both seasonal affective disorder and bright light therapy quickly captured considerable attention, both in the scientific community and with the general public. Several research groups launched clinical trial programs, and soon this experimental treatment was extended to other conditions, including nonseasonal mood disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, circadian-related sleep disorders and jet lag, eating disorders, and other behavioral syndromes (2, 3). An international organization (the Society for Light Treatment and Biological Rhythms) was created, and several journals that emphasized phototherapy and biological rhythms emerged. Despite the growth in clinical and research programs, there remained an absence of recognition and support for light therapy within many segments of the psychiatric treatment community. Most insurers do not offer reimbursement for this treatment, most residency training programs do not provide clinical training in phototherapy, and there is a sense that “the biological psychiatry establishment has regarded light therapy with a certain disdain and relegated it to the edge of the paradigm” (4).

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Council on Research requested that the APA Committee on Research on Psychiatric Treatments use the principles of evidence-based medicine to examine the efficacy of light therapy (J. Greden, personal communication). A work group was formed from members of the committee as well as outside consultants with expertise and experience in relevant disciplines. The work group completed a comprehensive literature review and meta-analyses. This report contains our findings about the efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders in adult patients.

Method

Search Strategy

We searched PubMed for medical literature published from Jan. 1, 1975, to July 25, 2003. The search terms included “phototherapy” (which was the original term applied to light therapy) and any of the following terms: 1) “seasonal affective disorder”; 2) “depressive disorder”; 3) “bipolar disorder”; 4) “sleep” or “sleep disorder”; 5) “circadian rhythm” or “jet lag” or “melatonin”; 6) “Alzheimer’s disease” or “dementia”; 7) “premenstrual dysphoric disorder” or “premenstrual syndrome” or “late luteal phase dysphoric disorder”; 8) “eating disorder” or “bulimia” or “obesity”; 9) “serotonin”; and 10) “attention” or “vigilance” or “reaction time.” We limited our search strategy to clinical trials reported in English. We supplemented these sources by using the same search terms in MEDLINE, searching the Cochrane Collaboration Library, and searching the bibliographies of prior reviews and relevant original articles. In this article, we present our findings for studies of light therapy for mood disorders.

Selection Criteria

Study groups were limited to adults who met a criterion-based mood disorder diagnosis. We restricted the age range to 18–65 years in an effort to define a standard for adequate treatment. We recognized that at each end of the age spectrum, the requirements for light therapy dosing may differ. For example, children and adolescents may differ from adults in the needed dose of light therapy, while elderly patients may require a higher dose of photons given the normal age-related clouding of the lens and ocular media, as well as possible reduction in the number of retinal photoceptors in that population. Accepted criterion standards were DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, the Research Diagnostic Criteria (5), and the Rosenthal criteria (1). Subsyndromal diagnoses were excluded.

The included studies were required to be randomized, controlled trials of patients in the acute phase of treatment and to have a credible placebo control condition. Defining a minimum treatment dose (lux by time) for the experimental bright light treatment intervention was complicated by the absence of an accepted standard definition of adequate dosing. In some studies, we found that the “placebo condition” consisted of light exposure that was greater than that for the “active condition” in other studies. After we reviewed standard textbooks and consulted with expert clinicians in the field, we arrived at a priori definitions of adequate light therapy dose and duration. For bright light treatment of seasonal affective disorder, the definition was a minimum of 4 days of at least 3,000 lux-hours (e.g., 1,500 lux for 2 hours or 3,000 lux for 1 hour). We required placebo comparison groups to receive a maximum of 300 lux. For dawn simulation studies, we required that the active intervention consist of increasing light exposure from 0 to 200–300 lux over 1.0–2.5 hours and that the placebo condition consist of an increase that was less than 5 lux and/or less than 15 minutes in duration. For studies of bright light augmentation, we applied the same minimum lux criteria as those for bright light treatment of seasonal affective disorder and required that bright light therapy was the primary adjunct to the standard treatment under investigation.

We required that the outcomes be psychiatric symptom measures, e.g., Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Seasonal Affective Disorders Version (6). Studies were excluded if gross protocol violations occurred (e.g., the study design was changed during the course of the trial).

Study Selection Process

Selection of the studies for inclusion involved two steps. First, two authors (R.N.G. and B.N.G.) independently reviewed the abstracts of all articles identified by the literature searches and excluded those for which they agreed that the eligibility criteria were not met. Next, the remaining articles were abstracted in detail (as described in the following) and the two authors made a final decision about inclusion or exclusion by consensus.

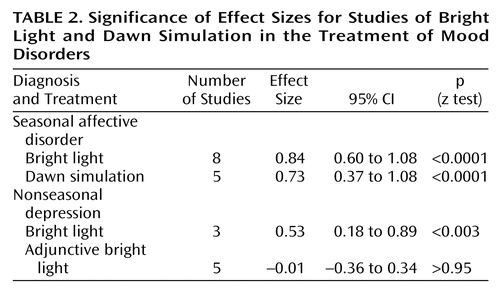

A total of 173 articles were identified and reviewed according to the selection criteria. This first step produced potentially relevant articles reporting 64 randomized, controlled trials (Figure 1). Of these, 50 involved patients with seasonal affective disorder and 14 involved patients with other depressive illnesses. These 64 trials received detailed abstraction, including clarification of subject group and selection, study design characteristics, and intervention parameters, to determine final eligibility. In addition, baseline demographic information and psychiatric outcome data were collected to allow direct comparisons of the experimental and control groups.

Data Analysis

All studies meeting the inclusion criteria were grouped by disorder and treatment type to produce four categories: bright light for seasonal affective disorder, bright light for nonseasonal depression, dawn simulation for seasonal affective disorder, and bright light as adjunctive treatment combined with conventional antidepressant pharmacotherapy for nonseasonal depression. The statistical information required for inclusion of a trial consisted of the mean score and standard deviation on a psychiatric symptom outcome measure and the number of subjects for each treatment condition; a trial was also included if the report contained sufficient information from which we could calculate the preceding data. For the articles in which the reported statistical detail was inadequate to allow meta-analytic procedures, several attempts were made to contact the corresponding author to gain access to the necessary raw data. For articles presenting outcomes from several treatment or control conditions, we pooled and analyzed the resulting statistics within conditions in order to use the largest study group available.

We employed standard meta-analytical methods, as described by Lipsey and Wilson (7). For each study, the standardized mean difference effect size and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated and adjusted with the Hedges correction for small sample bias (8). For each of the four meta-analyses, the weighted mean of the component effect sizes and its 95% CI was calculated with the inverse variance weights from each study. The statistical significance of each weighted mean effect size was tested nondirectionally at the 0.05 level by using the z test.

If the number of subjects was sufficient, we performed homogeneity analyses of our results. If the required data were available, we calculated odds ratios for the likelihood of remission, defined a priori as a final score on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale of 8 or less. We also applied the Q test, which uses the chi-square distribution to test the homogeneity of effect sizes across studies.

Results

Only 23 of the 173 studies identified during our literature search met our selection criteria (Figure 1). Of these, 20 distinct articles had sufficient data to allow inclusion in our meta-analysis (Table 1). One article (18) appeared to include a subset of patients who had been the subjects in a trial reported earlier (28), so the latter paper was excluded from this analysis. An additional report (9) contained the results of two experiments, one involving light therapy and another involving dawn simulation. Each was included in the appropriate, separate meta-analysis.

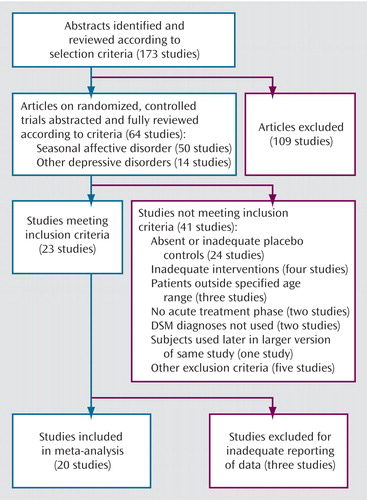

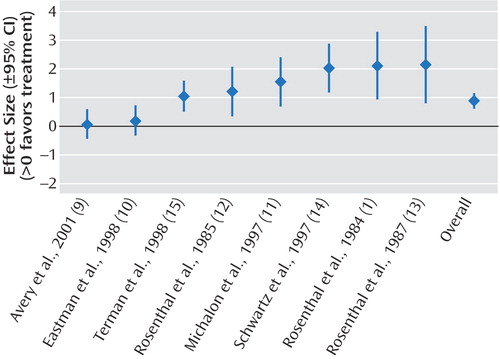

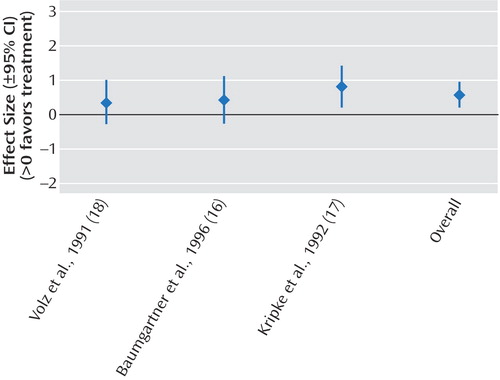

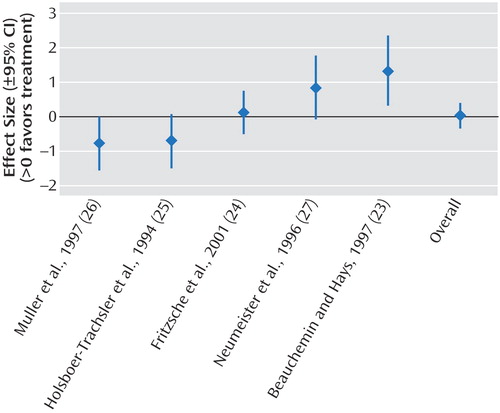

The results of the meta-analyses are shown in Table 2. We demonstrated significant effect sizes for bright light treatment of seasonal affective disorder (Figure 2), dawn simulation for seasonal affective disorder (Figure 3), and bright light treatment of nonseasonal depression (Figure 4). The effect size for bright light as an adjunctive treatment for nonseasonal depression was not significant (Figure 5).

Homogeneity analysis of the eight studies of bright light treatment of seasonal affective disorder was performed (for the other three meta-analyses, the number of studies was not large enough to support a Q test). The Q test indicated significant (p<0.0001) heterogeneity among studies; however, the effect sizes were consistently positive.

Odds ratios and their 95% CIs were calculated for the subset of four studies of bright light treatment of seasonal affective disorder for which the number of subjects who experienced remission was known. The summary estimate of risk of remission given treatment was an odds ratio of 2.9 (95% CI=1.6 to 5.4). The four study-specific odds ratios were significantly heterogeneous (p<0.04) but consistently positive.

Discussion

In our literature review, we found that most of the published research reports on the effects of light therapy in mood disorders did not meet recognized criteria for rigorous clinical trial design. There are several potential explanations for this observation. First, there are inherent challenges in creating an acceptable placebo (or even an active control) condition for light therapy. While it is relatively easy to create a placebo pill or capsule that is identical in appearance to an active medication formulation, it is more difficult to “blind” a subject when broad-spectrum intense white light is the active experimental intervention. The pharmaceutical industry, which has considerable resources devoted to research and development activities, funds much of the clinical trial research for potential new antidepressant pharmacotherapies. In contrast, there has not been a similarly endowed industry nor as sizable a market in place to support the development and testing of light therapy treatments. The history of the development of light therapy, which is inextricably interwoven with the development of the concept of seasonal affective disorder, not surprisingly was dominated in its early stages by a series of relatively small, investigator-initiated pilot projects. These researchers did not have access to resources of the magnitude of those available when pharmaceutical companies seek recognition by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration of the safety and efficacy of a new medication. Unfortunately, a consensus about standard approaches to study design issues (such as lux parameters for the active treatment, duration of an adequate light therapy trial, and characteristics of placebo control conditions) was not established in the early years of light therapy research. In too many cases, high standards of research design (such as random assignment to treatment conditions, adequate reporting of results statistics) were not followed. Not surprisingly, these conditions produced inconsistencies in the research literature. We found substantial variability in the selection of study groups and in the doses of both the active and control interventions for those trials meeting our selection criteria.

All of these factors have limited the conclusions that can be drawn from light therapy research. Past efforts to synthesize the available body of literature have been as challenging as the proverbial comparison of apples and oranges. More important, the limitations in much of the literature on light therapy research may have created the unsubstantiated impression that the treatment itself has limitations in terms of its efficacy.

When we analyzed the data from all available randomized, controlled trials that met our a priori standards, we demonstrated a significant reduction in depression symptom severity following bright light therapy in seasonal affective disorder and in nonseasonal depression, as well as a significant effect with dawn simulation in seasonal affective disorder. In other words, when the “noise” from unreliable studies is removed, the effects of light therapy are comparable to those found in many antidepressant pharmacotherapy trials (29).

Earlier reviews of light therapy yielded similar findings. Terman et al. (30) pooled data from 14 research groups that collectively studied 332 patients who received bright light therapy for seasonal affective disorder over a 5-year period, and they applied a pooled clustering technique in their analysis. Twenty-nine data sets were included. Unfortunately, the vast majority were not available for inclusion in our current analysis, because they consisted of personal communications, unpublished posters presented at meetings, and book chapters, as well as a few additional reports that did not meet our inclusion criteria. Thus, only two of their 29 data sets overlap with the 20 studies included in our meta-analyses, i.e., two studies by Rosenthal et al. (1, 12). Terman et al. (30) found that 2,500-lux light exposure for at least 2 hours/day for 1 week resulted in significantly more remission when administered in the early morning than in the evening or at midday. Treatments at each of these three administration times were significantly more effective than control treatments with dim light. Tam et al. (31) concluded that bright light therapy that utilized at least 2,500-lux white light for 2 hours/day and treatment with 10,000 lux for 30 minutes/day had comparable response rates and that both treatments were efficacious. They noted that more studies were needed before conclusions could be drawn about the efficacy of dawn simulation. They highlighted the methodological limitations of the literature, which included brief treatment periods, small study groups, and lack of replication.

Several caveats and limitations in our review and analyses should be noted. First, we limited our focus to efficacy and did not study the other key feature of all treatments, safety. Very few reports of the controlled studies contained data on side effects or toxicity. Several side effects of bright light therapy have been described elsewhere, including headache, eye strain, nausea, and agitation (32, 33). To our knowledge, there have been no reports to date of retinal toxicity in association with bright light treatment, and a 5-year follow-up study showed no adverse ocular effects (34). However, some psychotropic medications may increase photosensitivity, and further study of potential adverse effects of combined pharmacotherapy and light therapy is indicated. Light therapy, like other antidepressants, may be associated with a switch to hypomania or mania in vulnerable bipolar patients (35). Other rare potential side effects from bright light treatment may emerge only after the treatment has become more widely applied. Thus, any potential recommendation of light therapy for mood disorders, based on findings of efficacy in our meta-analyses, must be tempered by the acknowledgment that safety must also be considered. This important aspect of light therapy merits careful examination with additional long-term follow-up studies.

Another limitation in this study, as described in our methods section, is that we restricted our analyses to studies of a relatively homogeneous, clearly defined population (i.e., nongeriatric adult patients). There are published reports of light therapy for seasonal affective disorder in children (e.g., references 36 and 37) and for mood disorders in the elderly (38). These important patient populations merit separate consideration, and there is a need for a larger evidence base in these areas. An additional potential application of light therapy lies in the treatment of depression during pregnancy and in the postpartum period, when safe and effective alternatives to pharmacotherapy without potential toxicity for the fetus or newborn would be clearly desirable (39, 40). It should be noted that all of the studies of dawn simulation in our meta-analysis came from a single research group, and confirmation of their findings by others at different locations would be especially important in determining the generalizability of their results. Finally, by setting a reasonably high standard for study inclusion in our meta-analysis, we excluded many of the published reports in this area. One could argue, as Smith et al. (41) did in another context, that many small, “imperfect” studies can “converge on a true conclusion.” However, we agree with those who believe that meta-analyses based on flawed studies are not useful and that some bodies of data are inadequate for supporting a proper meta-analysis (42).

This study suggests that certain types of light therapy are effective in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder and other forms of depression. Much of the available literature is limited in terms of study design, and additional randomized, controlled trials with appropriate numbers of subjects are needed. Remaining questions of efficacy, safety, optimum dose, and the proper place of light therapy in the psychiatrist’s toolbox may be answered only after investigators in the field define and consistently adhere to standard approaches to essential components, such as definitions of acceptable parameters for active treatment and control conditions.

|

|

Presented in part at the 156th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, San Francisco, May 17–22, 2003. Received Feb. 18, 2004; revision received April 27, 2004; accepted May 26, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and the Committee on Research on Psychiatric Treatments, American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, Va. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Golden, Department of Psychiatry, Campus Box 7160, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7160; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. Selection of Studies for Meta-Analysis of Trials of Light Therapy for Mood Disorders

Figure 2. Effect Sizes in Studies of Treatment of Seasonal Affective Disorder With Bright Light

Figure 3. Effect Sizes in Studies of Treatment of Seasonal Affective Disorder With Dawn Simulation

Figure 4. Effect Sizes in Studies of Treatment of Nonseasonal Depression With Bright Light

Figure 5. Effect Sizes in Studies of Treatment of Nonseasonal Depression With Bright Light as Adjunctive Treatment

1. Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, Lewy AJ, Goodwin FK, Davenport Y, Mueller PS, Newsome DA, Wehr TA: Seasonal affective disorder: a description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:72–80Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Terman M, Boulos Z, Campbell SS, Dijk D-J, Estman CI, Lewy AJ: Light treatment for sleep disorders: ASDA/SLTBR Joint Task Force Consensus Report. J Biol Rhythms 1995; 10:101–176Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Parry BL, Mahan AM, Mostofi N, Klauber MR, Lew GS, Gillin JC: Light therapy of late luteal phase dysphoric disorder: an extended study. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1417–1419Link, Google Scholar

4. Wirz-Justice A: Beginning to see the light. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:861–862Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773–782Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Williams JBW, Link MJ, Rosenthal NE, Terman M: Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Seasonal Affective Disorders Version (SIGH-SAD). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1988Google Scholar

7. Lipsey MW, Wilson DB: Applied Social Research Methods: Practical Meta-Analysis, vol 49. London, Sage Publications, 2000Google Scholar

8. Hedges LV: Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educational Statistics 1981; 6:107–128Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Avery DH, Eder DN, Bolte MA, Hellekson CJ, Dunner DL, Vitiello MV, Prinz PN: Dawn simulation and bright light in the treatment of SAD: a controlled study. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:205–216Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Eastman CI, Young MA, Fogg LF, Liu L, Meaden PM: Bright light treatment of winter depression: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:883–889Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Michalon M, Eskes GA, Mate-Kole CC: Effects of light therapy on neuropsychological function and mood in seasonal affective disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1997; 22:19–28Medline, Google Scholar

12. Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Carpenter CJ, Parry BL, Mendelson WB, Wehr TA: Antidepressant effects of light in seasonal affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:163–170Link, Google Scholar

13. Rosenthal NE, Skwerer RG, Sack DA, Duncan CC, Jacobsen FM, Tamarkin L, Wehr TA: Biological effects of morning-plus-evening bright light treatment of seasonal affective disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23:364–369Medline, Google Scholar

14. Schwartz PJ, Murphy DL, Wehr TA, Garcia-Borreguero D, Oren DA, Moul DE, Ozaki N, Snelbaker AJ, Rosenthal NE: Effects of meta-chlorophenylpiperazine infusions in patients with seasonal affective disorder and healthy control subjects: diurnal responses and nocturnal regulatory mechanisms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:375–385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Terman M, Terman JS, Ross DC: A controlled trial of timed bright light and negative air ionization for treatment of winter depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:875–882Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Baumgartner A, Volz HP, Campos-Barros A, Stieglitz RD, Mansmann U, Mackert A: Serum concentrations of thyroid hormones in patients with nonseasonal affective disorders during treatment with bright and dim light. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:899–907Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kripke DF, Mullaney DJ, Klauber MR, Risch SC, Gillin JC: Controlled trial of bright light for nonseasonal major depressive disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1992; 31:119–134Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Volz HP, Mackert A, Stieglitz RD, Muller-Oerlinghausen B: Diurnal variations of mood and sleep disturbances during phototherapy in major depressive disorder. Psychopathology 1991; 24:238–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Avery DH, Bolte MA, Cohen S, Millet MS: Gradual versus rapid dawn simulation treatment of winter depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53:359–363Medline, Google Scholar

20. Avery DH, Bolte MA, Dager SR, Wilson LG, Weyer M, Cox GB, Dunner DL: Dawn simulation treatment of winter depression: a controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:113–117Link, Google Scholar

21. Avery DH, Bolte MA, Wolfson JK, Kazaras AL: Dawn simulation compared with a dim red signal in the treatment of winter depression. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:180–188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Avery DH, Bolte MA, Ries R: Dawn simulation treatment of abstinent alcoholics with winter depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:36–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Beauchemin KM, Hays P: Phototherapy is a useful adjunct in the treatment of depressed in-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 95:424–427Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Fritzsche M, Heller R, Hill H, Kick H: Sleep deprivation as a predictor of response to light therapy in major depression. J Affect Disord 2001; 62:207–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Holsboer-Trachsler E, Hemmeter U, Hatzinger M, Seifritz E, Gerhard U, Hobi V: Sleep deprivation and bright light as potential augmenters of antidepressant drug treatment—neurobiological and psychometric assessment of course. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:381–399Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Muller MJ, Seifritz E, Hatzinger M, Hemmeter U, Holsboer-Trachsler E: Side effects of adjunct light therapy in patients with major depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 247:252–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Neumeister A, Goessler R, Lucht M, Kapitany T, Bamas C, Kasper S: Bright light therapy stabilizes the antidepressant effect of partial sleep deprivation. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 39:16–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Mackert A, Volz HP, Stieglitz RD, Muller-Oerlinghausen B: Effect of bright white light on non-seasonal depressive disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry 1990; 23:151–154Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Bech P, Cialdella P, Haugh MC, Hours A, Boissel JP, Birkett MA, Tollefson GD: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of fluoxetine v placebo and tricyclic antidepressants in the short-term treatment of major depression. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:421–428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Terman M, Terman JS, Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Stewart JM, Rafferty AB: Light therapy for seasonal affective disorder: a review of efficacy. Neuropsychopharmacology 1989; 2:1–22Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Tam EM, Lam RW, Levitt AJ: Treatment of seasonal affective disorder: a review. Can J Psychiatry 1995; 40:457–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Labbate LA, Lafer B, Thibault A, Sachs GS: Side effects induced by bright light treatment for seasonal affective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:189–191Medline, Google Scholar

33. Terman M, Terman JS: Bright light therapy: side effects and benefits across the symptom spectrum. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:799–808Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Gallin PF, Terman M, Reme CE, Rafferty B, Terman JS, Burde RM: Ophthalmologic examination of patients with seasonal affective disorder, before and after bright light therapy. Am J Ophthalmol 1995; 119:202–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Chan PK, Lam RW, Perry KF: Mania precipitated by light therapy for patients with SAD (letter). J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:454Medline, Google Scholar

36. Swedo SE, Allen AJ, Glod CA, Clark CH, Teicher MH, Richter D, Hoffman C, Hamburger SD, Dow S, Brown C, Rosenthal NE: A controlled trial of light therapy for the treatment of pediatric seasonal affective disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:816–821Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Sonis WA, Yellin AM, Garfinkel BD, Hoberman HH: The antidepressant effect of light in seasonal affective disorder of childhood and adolescence. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23:360–363Medline, Google Scholar

38. Kobayashi R, Fukuda N, Kohsaka M, Sasamoto Y, Sakakibara S, Koyama E, Nakamura F, Koyama T: Effects of bright light at lunchtime on sleep of patients in a geriatric hospital, I. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 55:287–289Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Oren DA, Wisner KL, Spinelli M, Epperson CN, Peindl KS, Terman JS, Terman M: An open trial of morning light therapy for treatment of antepartum depression. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:666–669Link, Google Scholar

40. Epperson CN, Terman M, Terman JS, Hanusa BH, Oren DA, Peindl KS, Wisner KL: Randomized clinical trial of bright light therapy for antepartum depression: preliminary findings. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:421–425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Smith ML, Glass JV, Miller TI: The Benefits of Psychotherapy. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980Google Scholar

42. Klein DF: Flawed meta-analyses comparing psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1204–1211Link, Google Scholar