Relapse Prevention in Patients With Bipolar Disorder: Cognitive Therapy Outcome After 2 Years

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: In a previous randomized controlled study, the authors reported significant beneficial effects of cognitive therapy for relapse prevention in bipolar disorder patients up to 1 year. This study reports additional 18-month follow-up data and presents an overview of the effect of therapy over 30 months. METHOD: Patients with DSM-IV bipolar I disorder (N=103) suffering from frequent relapses were randomly assigned into a cognitive therapy plus medication group or a control condition of medication only. Independent raters, who were blind to patient group status, assessed patients at 6-month intervals. RESULTS: Over 30 months, the cognitive therapy group had significantly better outcome in terms of time to relapse. However, the effect of relapse prevention was mainly in the first year. The cognitive therapy group also spent 110 fewer days (95% CI=32 to 189) in bipolar episodes out of a total of 900 for the whole 30 months and 54 fewer days (95% CI=3 to 105) in bipolar episodes out of a total of 450 for the last 18 months. Multivariate analyses of variance showed that over the last 18 months, the cognitive therapy group exhibited significantly better mood ratings, social functioning, coping with bipolar prodromes, and dysfunctional goal attainment cognition. CONCLUSIONS: Patients in the cognitive therapy group had significantly fewer days in bipolar episodes after the effect of medication compliance was controlled. However, the results showed that cognitive therapy had no significant effect in relapse reduction over the last 18 months of the study period. Further studies should explore the effect of booster sessions or maintenance therapy.

In the last few years, evidence for the efficacy of psychotherapy specific for bipolar disorder is emerging (1–3). We recently reported a randomized controlled study of a relapse prevention approach that showed significant beneficial short-term effects of cognitive therapy for up to 1 year (4). Over the 12-month period, the cognitive therapy group had significantly fewer bipolar episodes, fewer days in bipolar episodes, and fewer bipolar admissions. The cognitive therapy group also had significantly higher social functioning and showed less mood symptoms on the monthly mood questionnaires. However, given the frequent relapsing nature of bipolar disorder (5, 6), a longer-term follow-up period is of paramount importance if cognitive therapy is to be a successful form of treatment. Furthermore, cognitive therapy traditionally has a large skill acquisition component. If therapy results in skill acquisition, it should delay or prevent relapses. Hence, a longer-term follow-up period will provide an estimate of the enduring effect of cognitive therapy.

The purpose of this article is to report an additional 18 months of follow-up data for the original treatment trial, resulting in a total of 30 months of data (6 months of treatment and 2 years of follow-up evaluations). Apart from important clinical data such as bipolar episodes, the length of episodes, and social functioning, we also report changes in coping with bipolar prodromes and in cognitive dysfunctional beliefs.

Our primary hypotheses were as follows:

| 1. | Relative to subjects in a control condition, patients assigned to cognitive therapy would have fewer bipolar episodes and fewer days in bipolar episodes. | ||||

| 2. | Relative to subjects in a control condition, patients assigned to cognitive therapy would have higher social functioning, better coping strategies for bipolar prodromes, and lower dysfunctional high goal attainment attitudes. | ||||

Our secondary hypotheses were that compared with subjects in a control condition, patients assigned to cognitive therapy would have lower depression and mania mood scores and show better medication compliance.

Method

Procedure and Assessment

After the study had been fully explained, written informed consent was obtained. Patients who were found suitable for the study were randomly allocated either to the control condition (N=52) or to the cognitive therapy group (N=51). The computer-generated allocation sequence was concealed in sequentially numbered and sealed opaque envelopes. Patients in the control condition received “minimal psychiatric care,” which was defined as mood stabilizers at a recommended level according to the British National Formulary, with regular psychiatric follow-up as outpatients. The cognitive therapy group received on average 13.9 sessions (SD=5.5) of cognitive therapy plus “minimal psychiatric care” over 6 months.

Independent assessors blind to patient group status assessed patients at 6-month intervals with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (7) to determine DSM-IV bipolar episodes. The other instruments used in the interview were the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (8), Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Rating Scale (9), Coping With Bipolar Prodromes Schedule (10), and the Social Functioning Schedule (11). Patient descriptions of coping with bipolar prodromes were transcribed verbatim. Raters blind to patient group status and time of interview rated patients’ ability to cope with bipolar prodromes. Interrater reliability was good (mania prodromes: kappa=0.69, SE=0.13; depression prodromes: kappa=0.79, SE=0.03). Patients also completed the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (12) and a medication compliance schedule every 6 months. Patients’ key workers were also asked to fill in the medication compliance schedule to obtain collateral reports of patient drug compliance.

Individual Cognitive Therapy

Cognitive therapy was defined by our cognitive therapy treatment manual (13), the new elements of which include 1) using a diathesis-stress model emphasizing the need for combined medication and psychological therapies; 2) the use of cognitive therapy skills to monitor prodromes and to modify behavior to prevent prodromal stages from developing into full-blown episodes; 3) promoting the importance of regular sleep and routine; and 4) targeting extreme striving attitudes and behavior. The four therapists were clinical psychologists (three male and one female) with a minimum of 5 years of postqualification experience. All therapy sessions were audiotaped for weekly peer supervision, which lasted an hour. Therapy consisted of 12–18 individual sessions within the first 6 months and two booster sessions in the second 6 months. In reality, therapy lasted about 6 months. Patients in the cognitive therapy group had an average of 13.9 sessions (SD=5.5). Eight patients terminated cognitive therapy prematurely before the sixth session (mean number of sessions=2.6, SD=1.8). All patients in the inadequate treatment group were included in “intent-to-treat” analyses whenever possible.

Patients

Patients in this study fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder. In order to identify a subgroup vulnerable to relapse, patients also had to have had at least two episodes in the last 2 years or three episodes in the last 5 years prior to recruitment. The only two exclusion criteria were actively suicidal (score of 3 on the Beck Depression Inventory suicide item) or currently fulfilling criteria for a substance use disorder. The characteristics of the subjects in the cognitive therapy and control condition groups are summarized in Table 1.

Instruments

| 1. | The Mania Rating Scale (9) consists of 11 items that reflect common manic symptoms such as motor activity, flight of thoughts, voice/noise level, and amount of sleep. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale. A total score of 0–5 is interpreted as no mania; 6–9=hypomania (mild); 10–14=probable mania; ≥15=definite mania. The scale has good interrater reliability and construct validity. | ||||

| 2. | For the Coping With Bipolar Prodromes Schedule (10), patients were asked, from their experience of past episodes, what the early warnings (prodromes) were that made them think they were “going either high or low” and what they did when they had these prodromes. Patient reports of prodromes and the way they coped with them for both depression and mania were recorded verbatim. Coping was rated on a 7-point scale (0=poor; 3=adequate; 6=extremely well). | ||||

| 3. | The Social Functioning Schedule (11) is an observer-rated scale based on a semistructured interview with patients that provides a quantitative assessment of social performance in the last month. The interview is directed toward actual behavior and performance over eight areas of social performance, each rated on a 4-point scale. In the original paper, the authors reported a better than chance interrater agreement. The interrater reliability in this study ranged from kappa of 0.91 to 0.76 for the different areas of social functioning with 10 training cases. A slightly modified version of the schedule was used to interview key relatives of the patients. | ||||

| 4. | The short version of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale for Bipolar Disorder (12) consists of 24 items. It is derived from a principal component analysis study that used 143 patients with bipolar I disorder in which three factors were derived. Factor 1, “goal attainment,” accounted for 25.0% of the total variance. Factor 2, “dependency,” accounted for 11.0% of the total variance. Factor 3, “achievement,” accounted for 8.2% of the total variance. The goal attainment subscale was thought to capture the highly motivated attitudes in the cognitive model for bipolar affective disorder. | ||||

| 5. | The medication compliance questionnaire reported compliance with any prescribed mood stabilizers. Respondents had a choice of noting whether the patient in the past month had 1) never missed taking their medication, 2) missed taking it once or twice, 3) missed taking it between three to seven times, 4) missed taking it more than seven times, or 5) stopped taking it altogether (14). | ||||

Data Analysis

Differences between the cognitive therapy and control conditions were assessed by a chi-square test for dichotomous variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Cox regression was used for survival analysis, with the number of weeks to the first bipolar episode as the dependent variable. Logistic regression was used to compare the proportions of patients who relapsed in the two groups. Where applicable, adjustments for differences in the relevant measures at baseline were carried out by analysis of covariance or logistic regression. The main outcomes, which were continuous scales, were tested for group differences by using a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA), covarying for the same variables measured at baseline. Univariate tests were carried out to identify the dependent variables that contributed most to the significant omnibus test. All analyses were on an intent-to-treat basis, and all p values were two-tailed.

Results

Survival Analysis

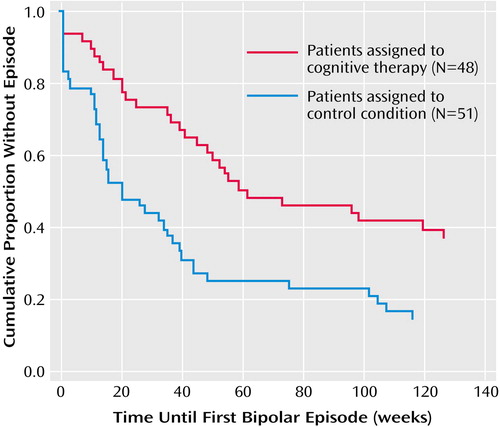

Figure 1 depicts the survival curves of the two groups over the 30-month period for bipolar episodes. The actuarial cumulative relapse rates for patients in the cognitive therapy and control conditions, respectively, were 63.8% (N=30 of 47) and 84.3% (N=43 of 51) for bipolar episodes, 50.0% (N=23 of 46) and 67.4% (N=31 of 46) for manic/hypomanic episodes, and 38.6% (N=17 of 44) and 66.7% (N=32 of 48) for depressive episodes. After controlling for the previous number of episodes and medication compliance during the whole 30 months, the between-group differences were significant for bipolar episodes (hazard ratio=0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.29–0.85; p<0.02) and depressive episodes (hazard ratio=0.38, 95% CI=0.19–0.75; p<0.006). However, the difference was not significant for manic/hypomanic episodes (hazard ratio=0.71, 95% CI=0.38–1.35; p=0.30).

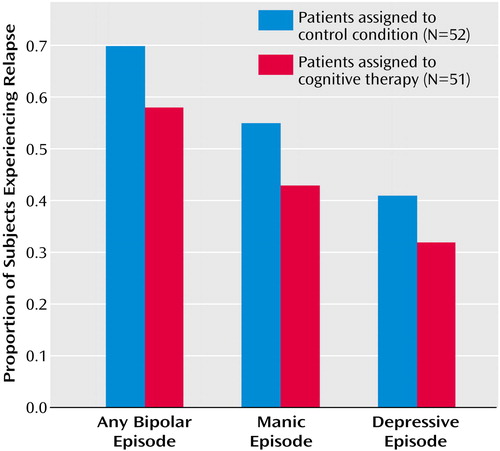

Bipolar Episodes Over the Last 18 Months

Over the 18-month follow-up period, there was a nonsignificant difference between the cognitive therapy and control condition groups in the proportion of subjects who had at least one relapse (57.8% [N=26 of 45] and 69.6% [N=32 of 46], respectively). Figure 2 depicts the total and type of episodes experienced during the last 18 months of the study for the two groups.

Days in Bipolar Episodes

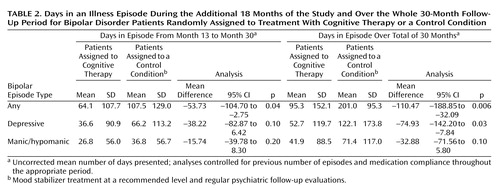

Table 2 summarizes the mean number of days that patients in the cognitive therapy and the control condition groups were in an illness episode during the additional 18 months of the study and over the whole 30-month follow-up period. During the additional 18 months, after the number of previous episodes and medication compliance over 30 months were controlled, the intent-to-treat analyses showed that the cognitive therapy group had significantly fewer days in bipolar episodes than the control condition group.

Clinical Ratings

There were significant correlations between the total raw scores of the Social Functioning Schedule and Hamilton depression scale at month 18 (r=0.65, df=77, p<0.02), month 24 (r=0.62, df=67, p<0.02), and month 30 (r=0.53, df=61, p<0.02). Moreover, there were significant correlations between ratings for coping with mania prodromes and total score on the Social Functioning Schedule at month 18 (r=–0.26, df=72, p<0.05), month 24 (r=–0.33, df=67, p<0.02), and month 30 (r=–0.29, df=69, p<0.05). Ratings for coping with depression prodromes and coping with mania prodromes also correlated significantly at month 18 (r=0.68, df=74, p<0.02, two-tailed), month 24 (r=0.71, df=68, p<0.02), and month 30 (r=0.54, df=75, p<0.02).

The scores of the Mania Rating Scale, Hamilton depression scale, Social Functioning Schedule, and Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (goal attainment subscale) and ratings for coping with mania prodromes and coping with depression prodromes at months 18, month 24, and month 30 were analyzed in a MANCOVA to test for differences between the two groups. The scores of these same variables at baseline plus patient reports of medication compliance and number of previous episodes were used as covariates. The omnibus test for group differences was significant (Wilks’s lambda=0.18, f=3.12, df=18, p<0.03). Table 3 summarizes the results of the univariate tests from the MANCOVA. The cognitive therapy group consistently showed a tendency to perform better than the control condition group at every time point on all six measures. Differences in Dysfunctional Attitude Scale goal attainment at month 18, social functioning at month 24, coping with mania and depression prodromes at month 24, and mania ratings at month 30 reached statistical significance.

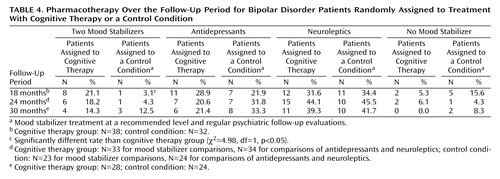

Treatment Variables

Table 4 summarizes the proportion of patients prescribed two mood stabilizers, antidepressants, neuroleptics, or no mood stabilizers. With the exception of two mood stabilizers prescribed at month 18, there were no significant differences between the two groups at any time point. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the dropout rates between patients who were prescribed one or two mood stabilizers or antipsychotics or no antipsychotics at any time point throughout the study.

There was no statistically significant difference in the mean number of psychiatric appointments during the last 18 months (cognitive therapy group: mean=7.2 [SD=5.7]; control condition group: mean=7.4 [SD=7.3]). According to self reports, the cognitive therapy group was significantly more compliant with medication than the control condition group at month 24 (mean=1.4 [SD=0.9] versus 2.2 [SD=1.5], respectively; t=–2.3, df=32.2, p<0.05) and at month 30 (mean=1.5 [SD=0.9] versus 2.2 [SD=1.3]; t=1.9, df=35.3, p<0.05). At month 18 the difference was in the predicted direction but not statistically significant (cognitive therapy group: mean=1.5, SD=0.9; control condition group: mean=1.7, SD=1.2). There was a significant correlation between reports of key workers and patients (r=0.60, df=52, p<0.01).

Discussion

In a previous study (4), we reported that patients assigned to cognitive therapy fared significantly better than subjects in a control condition in terms of relapse and days in a bipolar episode over the first 12 months of the study. Taking the 30 months as a whole, patients in the cognitive therapy group did significantly better in actuarial cumulative relapse rates than those in the control condition, even when the number of previous episodes and medication compliance were controlled. When the episodes were divided into depression and mania/hypomania, the differences were significant for depression but not for mania/hypomania. This is similar to the initial analysis of Interpersonal Social Rhythm Therapy, which found a significant effect in preventing depression symptoms but not manic symptoms (5). However, the overall effect of relapse prevention was strongest during the first 12 months of the 30-month study period. This included 6 months of therapy and the following 6 months. There was no evidence that cognitive therapy had a significant effect in preventing relapse over the last 18 months. The effect was less robust as therapy became more distant. Maintenance therapy in cognitive therapy (15) and interpersonal therapy (16) has been found to be beneficial in unipolar depression. Our findings suggest that some form of maintenance therapy may be helpful to boost the beneficial effect of cognitive therapy.

However, the number of patients who had suffered from a bipolar episode cannot be the sole outcome measure. The length of bipolar episodes can vary. Bipolar patients can suffer from chronic depression that lasts for months as opposed to short manic episodes that last a couple of weeks. Hence, the duration in which patients are in episodes is an important outcome. As in the first 12 months, the cognitive therapy group had significantly fewer days in bipolar episodes over the last 18 months of the study period.

Patients in the cognitive therapy group performed consistently equal to or better than subjects in the control condition in terms of mood ratings, social functioning, coping with bipolar prodromes, and dysfunctional goal attainment cognition over the last 18 months of the study. The omnibus test for group differences was significant. In our previous report, patients in the cognitive therapy group exhibited significantly better coping strategies for mania and depression prodromes at the end of therapy (4). In this follow-up study, the cognitive therapy group showed a tendency to report better coping strategies over the last 18 months of the study and significantly better coping with depression and mania prodromes at month 24. Highly driven and extreme goal attainment beliefs were identified as potential vulnerability factors (7) for extreme goal-pursuing behavior, which would disrupt sleep and daily routines and lead to more episodes. In this study, therapists targeted these attitudes. There was a vigorous attempt to challenge these beliefs, and the cognitive therapy group scored significantly lower in these dysfunctional beliefs at 6 and 18 months.

The beneficial effects for the cognitive therapy group could not be attributed to more frequent psychiatric outpatient appointments and the medication prescribed to patients. There were no significant differences between the two groups in frequency of outpatient appointments. The only difference between the two groups in medication prescribed was that at month 18 significantly more patients in the cognitive therapy group were prescribed two mood stabilizers than patients in the control condition. Both patient and clinician reports suggest that patients in the cognitive therapy group were more compliant with medication than those in the control condition. However, this higher level of compliance or the number of previous episodes may not account entirely for the treatment benefits in the cognitive therapy group, since we controlled for the number of previous episodes and medication compliance throughout the study period for all major outcomes.

There are four limitations of our follow-up study. First, we did not control for the extent of pharmacological or psychological treatment over the follow-up period. Four patients in the control condition received psychological therapy during the follow-up period, although none of the cognitive therapy group received additional psychotherapy. However, the aim of the study was to test the beneficial effects of adding cognitive therapy to a commonly used regimen of pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder patients. Second, there was a lack of control for nonspecific effects of therapy. Hence, we cannot rule out the possibility that the advantageous effect of cognitive therapy was due to attentional effect. Third, the assessment of relapse status was carried out every 6 months. Depression and hypomanic symptoms between the assessments could have been missed. Hence, it was difficult to exclude the possibility that cognitive therapy eliminated bipolar episodes by shifting patients from clinical episodes to more subtle pathological states. Last, we did not measure systematically subjects’ adherence to circadian-rhythm-related routines.

Overall, our study showed that cognitive therapy can prevent relapses in a group of bipolar disorder patients who had experienced frequent relapses despite the prescription of mood stabilizers. Furthermore, there was some evidence that patients who had received therapy had higher social functioning and coped better with bipolar prodromes throughout the study period. Taken together, the findings of this study support the conclusion that cognitive therapy is a worthy addition to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of bipolar affective disorder, particularly for those who suffer from frequent relapses despite the use of mood stabilizers. However, the effect was strongest during the 6 months when patients were receiving cognitive therapy and the 6 months following therapy. As therapy became more distant, the beneficial effect became weaker. Further study should explore the effect of maintenance therapy or booster sessions.

|

|

|

|

Received Feb. 27, 2003; revisions received Sept. 9, 2003, and Jan. 12, 2004; accepted March 18, 2004. From the Department of Psychology, the Department of Psychological Medicine, and the Social, Genetic, and Developmental Psychiatry Research Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, U.K. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Lam, Psychology Department (P077), Henry Wellcome Bldg., Institute of Psychiatry, DeCrespigny Park, London SE5 8AF, U.K.; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank Natalie Kerr and Gina Parr-Davis for their help in data collection.

Figure 1. Time Until Relapse for Bipolar Disorder Patients Randomly Assigned to Treatment With Cognitive Therapy or a Control Condition

Figure 2. Relapse Rates Over an 18-Month Follow-Up Period for Bipolar Disorder Patients Randomly Assigned to Treatment With Cognitive Therapy or a Control Condition

1. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Torrent C, Comes M, Corbella B, Parramon G, Corominas J: A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:402–407Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Miklowitz DJ, Simoneau TL, George EL, Richards JA, Kalbag A, Sachs-Ericsson N, Suddath R: Family-focused treatment of bipolar disorder: 1-year effects of a psychoeducational program in conjunction with pharmacotherapy. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:582–592Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Frank E: Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy prevents depressive symptomatology in bipolar I patient. Bipolar Disord Suppl 1999; 1:13Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lam DH, Watkins ER, Hayward P, Bright J, Wright K, Kerr N, Parr-Davis G, Sham P: A randomized controlled study of cognitive therapy for relapse prevention for bipolar affective disorder: outcome of the first year. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:145–152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Solomon DA, Keitner GI, Miller IW, Shea MT, Keller MB: Course of illness and maintenance treatments for patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:5–13Medline, Google Scholar

6. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Endicott J, Mueller TI: Bipolar I: a five-year prospective follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993; 181:238–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996Google Scholar

8. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bech P, Rafaelsen OJ, Kramp P, Bolwig TG: The Mania Rating Scale: scale construct and inter-observer agreement. Neuropharmacology 1978; 17:430–431Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lam D, Wong G: Prodromes, coping strategies, insight and social functioning in bipolar affective disorders. Psychol Med 1997; 27:1091–1100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hurry J, Sturt E, Bebbington P, Tennant C: Socio-demographic associations with social disablement in a community sample. Soc Psychiatry 1983; 18:113–121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Lam D, Wright K, Smith N: Dysfunctional assumptions in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2004; 79:193–199Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lam DH, Jones S, Hayward P, Bright J: Cognitive Therapy for Bipolar Disorder: A Therapist’s Guide to Concepts, Methods and Practice. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1999Google Scholar

14. Lam DH, Bright J, Jones S, Hayward P, Schuck N, Chisholm D, Sham P: Cognitive therapy for bipolar illness—a pilot study of relapse prevention. Cognit Ther Res 2000; 24:503–520Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Jarrett RB, Kraft D, Doyle J, Foster BM, Eaves GG, Silver PC: Preventing recurrent depression using cognitive therapy with and without a continuation phase: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:381–388Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, Cornes C, Jarrett DB, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ: Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1093–1099Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar