The Construct of Minor and Major Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the frequency of major and minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease and determined whether these types of depression have a different functional and psychopathological impact and whether there is a change in the prevalence of major and minor depression throughout the stages of Alzheimer’s disease. METHOD: A consecutive series of 670 patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; specific instruments to rate the presence and severity of depression, anxiety, apathy, irritability, delusions, pathological affective crying, performance of activities of daily living, and social functioning; and a standardized neuropsychological evaluation. Diagnoses of major and minor depression were generated from DSM-IV criteria. RESULTS: Twenty-six percent of the patients had major depression, 26% had minor depression, and 48% were not depressed. Major depression was significantly associated with sad mood in all three stages of the illness, although this association dropped significantly for minor depression in severe Alzheimer’s disease. Both major and minor depression were significantly associated with more severe psychopathology, functional impairments, and social dysfunction. Depressive symptoms that most strongly discriminated between Alzheimer’s disease patients with and without sad mood were guilty ideation, suicidal ideation, loss of energy, insomnia, weight loss, psychomotor retardation/agitation, poor concentration, and loss of interest. CONCLUSIONS: Our study demonstrates that DSM-IV criteria for major and minor depression identify clinically relevant syndromes of depression in Alzheimer’s disease, mild levels of depression can produce significant functional impairment, and the severity of psychopathological and neurological impairments increases with increasing severity of depression.

Although depressive mood is a frequent complaint of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, the diagnosis of depressive disorders in dementia is still a complex issue. Early studies diagnosed depression among patients with Alzheimer’s disease using arbitrary cutoff scores on depression rating scales (1). To avoid rating symptoms of dementia as secondary to depression, some studies excluded so-called physical and autonomic symptoms of depression from the rating scales (2, 3). Other studies replaced physical with psychological symptoms of depression or accepted both physical and psychological symptoms of depression, regardless of their potential association with the underlying dementia (4).

In one study, we used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (5) to diagnose depression in a consecutive series of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and examined the validity of DSM-IV criteria for major depression for this condition (6). The main finding was that patients with sad mood (present most of the day, nearly every day, over 2 weeks) scored significantly higher on each of the DSM-IV criteria for major depression, except loss of appetite, than Alzheimer’s disease patients without sad mood (6). Only 4% of 92 Alzheimer’s disease patients with sad mood failed to meet the DSM-IV criteria for either major or minor depression.

A workshop organized by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) proposed standardized diagnostic criteria for depression in Alzheimer’s disease (4, 7). These criteria are similar to the DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode, but loss of interest was revised to indicate loss of pleasure in response to social contact, and specific criteria for irritability and social isolation were included. A significant departure from the criteria for a major depressive episode is that the NIMH criteria for depression in Alzheimer’s disease require at least three symptoms for diagnosis, compared to five or more symptoms for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode. One potential limitation is that requiring only three criteria for a diagnosis of depression in Alzheimer’s disease could greatly increase the risk of overdiagnosing depression among these patients. This is most likely to happen in the late stages of dementia, when severe cognitive and motor deficits may reduce the specificity of depressive symptoms. To our knowledge, the threshold at which depression should be diagnosed, as well as whether minor and major depression are valid constructs in Alzheimer’s disease, has not been empirically examined.

The present study included a consecutive series of 670 patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease and mild, moderate, or severe dementia who were assessed with a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation. The main aims of the study were to examine the frequency of major and minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease, to determine whether these types of depression have a different functional and psychopathological impact, and to examine whether there is a change in the prevalence of major and minor depression throughout the worsening stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Method

The Alzheimer’s disease group included a consecutive series of outpatients visiting the dementia clinic of a tertiary care center in Buenos Aires between January 1996 and October 2002 for evaluation and treatment of progressive cognitive decline. The inclusion criteria were the following:

| 1. | Meeting criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association for probable Alzheimer’s disease (8) | ||||

| 2. | No history of closed head injuries with loss of consciousness, strokes, or other neurological disorder with involvement of the CNS | ||||

| 3. | Normal results on laboratory tests (to rule out other etiologies of dementia) | ||||

| 4. | No focal lesions on a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan | ||||

| 5. | A Hachinski Ischemic (9) score <4 | ||||

The institutional human subjects committee approved the study.

After the methods of the study had been fully explained, written informed consent was obtained from the patients and their respective caregivers.

Psychiatric Examination

A psychiatrist who was blind to the neurological and neuropsychological findings assessed the patients with the following instruments:

| 1. | The SCID (5) is a semistructured diagnostic interview for making major axis I DSM-III-R diagnoses. The psychiatrist administered the SCID to the patient and at least one first-degree relative. Sad mood was rated according to the DSM-III-R definition (i.e., sad mood present most of the day, nearly every day, over 2 weeks). Based on the SCID responses, a DSM-III-R axis I diagnosis of major depressive episode or a DSM-III-R research diagnosis of minor depression disorder was made. The reliability of the SCID was assessed as part of a previous study (6). Test-retest reliability was examined in 14 patients (four with major depression, three with minor depression, and seven without depression). The patients and their respective first-degree relatives were assessed in two separate interviews no more than 2 weeks apart. There was perfect (100%) agreement of depression diagnosis and depression type for both assessments. Interrater reliability was examined in 15 patients and their respective first-degree relatives by two raters (who were blind to each other’s ratings) in a single interview for each subject. There was perfect agreement (100%) for major depression (N=5) and 93% agreement for minor depression (one patient was diagnosed with minor depression by the senior interviewer and as not depressed by the second interviewer). | ||||

| 2. | The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (10) is an 11-item examination found to be valid and reliable in assessing a limited range of cognitive functions in a global manner. | ||||

| 3. | The Clinical Dementia Rating (11) is a global device for rating dementia stages. | ||||

| 4. | The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (12) is a 17-item interviewer-rated scale that measures psychological and autonomic symptoms of depression. | ||||

| 5. | The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (13) is an 11-item interviewer-rated scale that measures the severity of generalized or persistent anxiety. | ||||

| 6. | The Apathy Scale (14) includes 14 items that are scored by the patient’s relative or caregiver. Apathy was diagnosed with the diagnostic scheme detailed in a previous publication (15). We have demonstrated the reliability and validity of the Apathy Scale in Alzheimer’s disease (14). | ||||

| 7. | The Irritability Scale (14) is a 14-item scale that is rated by the patient’s relative or caregiver. Following our previous findings, the patients with an Irritability Scale score above 20 points were considered irritable (14). We have demonstrated the validity and reliability of this scale in Alzheimer’s disease (14). | ||||

| 8. | The Dementia Psychosis Scale (16) is an 18-item caregiver-rated scale that quantifies the severity and types of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease patients at the time of their psychiatric evaluation. We have demonstrated the validity and reliability of this scale in Alzheimer’s disease (16). | ||||

| 9. | The Social Ties Checklist (17) is a 10-item scale that measures the quantity and quality of social supports | ||||

| 10. | The Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale (18) is an interviewer-rated scale that quantifies aspects of pathological affect, including the duration of the episodes, their relation to external events, the degree of voluntary control, the inappropriateness in relation to emotions, and the degree of resultant distress. We have demonstrated the validity and reliability of this scale in Alzheimer’s disease (18). | ||||

| 11. | The Functioning Independence Measure (19) is an 18-item ordinal scale that assesses self-care, sphincter control, mobility, locomotion, communication, and social cognition. Higher scores indicate fewer impairments in activities of daily living. | ||||

The patients with Alzheimer’s disease were first interviewed with the full psychiatric assessment, except for the SCID. Simultaneously, caregivers, who were blind to the results of these interviews, rated the patients’ behaviors with the same instruments. Finally, the psychiatrist administered the SCID to each patient with both the patient and the caregiver present. Signs and symptoms of depression were scored with the inclusive method without the need to interpret whether a clinical feature was attributable to the neurodegenerative process.

Neurological Examination

The patients had full neurological examinations and were assessed with the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (20) by a neurologist who was blind to their psychiatric ratings.

Neuropsychological Examination

The cognitive evaluation was carried out by a neuropsychologist who was blind to the other clinical findings and consisted of the following tests:

| 1. | The Boston Naming Test (21) examines the ability to name pictured objects. | ||||

| 2. | The Controlled Oral Word Association Test (22) examines access to semantic information with time constraints. | ||||

| 3. | The Buschke Selective Reminding Test (23) measures verbal learning and memory during a multiple-trial list-learning task (long-term retrieval was used as the outcome measure). | ||||

| 4. | The Digit Span Test (24) examines auditory attention and includes two parts. In the first part (digits forward), the patient is asked to repeat a string of numbers exactly as it is given, whereas in the second (digits backward), the patient must repeat the digit string in reverse order. | ||||

| 5. | The Block Design Test (24) examines constructional praxis. | ||||

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out by using means, standard deviations, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with post hoc planned comparisons (Tukey’s test for unequal samples). Frequency distributions were calculated with chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact test. All p values are two-tailed.

Results

One hundred seventy-seven of the 670 Alzheimer’s disease patients (26%) had major depression, 177 patients (26%) had minor depression, and 316 patients (48%) were not depressed. There were no significant between-group differences in their main demographic characteristics (Table 1).

Depression and Severity of Alzheimer’s Disease

A hypothesis of unequal frequency of depression based on the stages of Alzheimer’s disease was statistically substantiated (χ2=16.7, df=4, p<0.01). Although the frequency of minor depression increased from 21% (46 of 217 patients) in the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s disease to 45% (32 of 71 patients) in the severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease, euthymia declined from 50% (109 of 217 patients) in the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s disease to 31% (22 of 71 patients) in the severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease (χ2=14.9, df=1, p<0.0001). Ninety-one percent of the patients (89 of 98) with major depression had a depressed mood in the mild stage of Alzheimer’s disease, 90% (56 of 62 patients) in the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s disease, and 94% (16 of 17 patients) in the severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease, indicating that the SCID was applied appropriately in all stages of the illness. Seventy-five percent of the patients (74 of 99) with minor depression and mild Alzheimer’s disease had sad mood (as ascertained by a score of 3 points on the respective SCID item) compared to 76% (35 of 46 patients) in the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s disease and 44% (14 of 32 patients) in the severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease (χ2=14.9, df=4, p<0.005). This finding suggests that the patients’ perception of mood may be altered unless the depression itself is severe. The frequency of patients with three symptoms of depression (according to the NIMH criteria for depression in Alzheimer’s disease) but without sad mood was 22% (22 of 100 patients) in mild Alzheimer’s disease, 23% (six of 26 patients) in moderate Alzheimer’s disease, and 41% (13 of 32 patients) in severe Alzheimer’s disease.

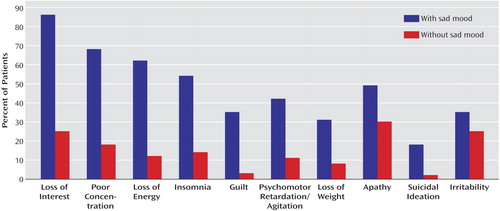

We also examined the association of sad mood with the different DSM-IV criteria for major depression and with the presence of apathy and irritability. Based on the responses to the SCID item rating sad mood, the patients were divided into those without sad mood (i.e., a score of 1 [absent]) (N=262) and those with sad mood (i.e., a score of 3 [threshold]) (N=316). (Patients with a score of 2 [i.e., subthreshold] were not included in this analysis.) (Figure 1). We calculated a ratio for each DSM-IV criterion of major depression and for the constructs of apathy and irritability using the following formula: percentage positive for patients with sad mood minus percentage positive for patients without sad mood over the sum of both. This ratio was highest (i.e., most strongly associated with sad mood) for guilty ideation (84%), followed by suicidal ideation (80%), loss of energy (68%), insomnia (59%), weight loss (59%), psychomotor retardation/agitation (58%), poor concentration (58%), loss of interest (55%), apathy (24%), and irritability (17%).

Comorbidity of Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease

The frequency of delusions was lowest in Alzheimer’s disease patients without depression and highest in patients with major depression (Table 1). A similar distribution (i.e., major depression > minor depression > no depression) was found for scores of depression, anxiety, apathy, pathological affective crying, and parkinsonism. The patients with either major or minor depression scored significantly worse than the nondepressed group on the Functioning Independence Measure and the Social Ties Checklist, but there were no significant differences between major depressed patients and minor depressed patients on these variables.

To determine whether the differences observed between the patients with minor depression or no depression resulted from the higher frequency of severe dementia in the group with minor depression, we restricted the analysis to patients with mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease. The patients with minor depression still had significantly worse scores than the nondepressed patients on ratings of depression (Hamilton depression scale score: mean=12.2, SD=4.7, versus mean=5.4, SD=4.1, respectively) (t=13.2, df=437, p<0.0001), anxiety (Hamilton anxiety scale score: mean=8.3, SD=6.3, versus mean=5.7, SD=5.5) (t=398, df=402, p<0.0001), apathy (Apathy Scale score: mean=21.4, SD=8.0, versus mean=18.5, SD=9.1) (t=3.13, df=400, p=0.001), pathological affective crying (Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale score: mean=4.9, SD=5.0, versus mean=2.2, SD=4.1) (t=5.00, df=336, p<0.0001), and parkinsonism (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale score: mean=14.9, SD=13.6, versus mean=8.9, SD=9.0) (t=4.79, df=332, p<0.0001). No significant differences were found on the remaining clinical variables.

Neuropsychological Findings

To avoid floor effects, the statistical analysis included only patients with either mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease (N=599). Eighty-four patients had one or more missing values and had to be excluded from the statistical analysis. A two-way ANCOVA (three groups [major, minor, and not depressed] on scores from six cognitive tests, with MMSE scores as a covariate) showed a significant overall effect (Rao’s R=2.04, df=12, 888, p<0.05). On post hoc comparisons, the patients with major depression had significantly lower scores than the patients with no depression on the Block Design Test (t=3.45, df=380, p<0.001), but there were no significant between-group differences on the remaining neuropsychological variables (Table 1).

Discussion

We examined the frequency and clinical correlates of major and minor depression in the different stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and there were several important findings. First, the patients meeting the DSM-IV criteria for either minor or major depression had more severe social dysfunction and greater impairment in activities of daily living than the nondepressed Alzheimer’s disease patients. Second, the patients with major depression had more severe anxiety, apathy, delusions, and parkinsonism than the patients with minor depression, suggesting that the severity of psychopathological and neurological impairments in Alzheimer’s disease increases with increasing severity of depression. On the other hand, the patients with major depression or minor depression had similar deficits in activities of daily living and social functioning, suggesting that even mild levels of depression are significantly associated with increased functional impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Finally, the syndrome of minor depression was associated with less mood change in severe compared to mild or moderate stages of Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that the symptoms of depression may change with increasing severity of Alzheimer’s disease.

Before further comments, several limitations of our study should be pointed out. First, 14% of the patients with mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease had to be excluded from the neuropsychological evaluation owing to missing data. However, the proportions of patients with major, minor, or no depression after a full neuropsychological evaluation (26%, 24%, and 50%, respectively) were similar to the proportions of depression in our full study group (27%, 27%, and 46%, respectively). Although all 670 patients were assessed with the SCID, the Hamilton depression scale, and the MMSE, incomplete evaluations resulted from missing data on the remaining instruments, which ranged from 8% for the Hamilton anxiety scale to 26% for the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. However, the proportion of depressed patients who were assessed with the various instruments was similar to the proportion of depressed patients in the full group. Second, our study group consisted of patients attending a dementia clinic at a tertiary care center, which may have biased our findings toward more severe cases. In spite of these limitations, this is, to our knowledge, among the few studies of mood disorders in Alzheimer’s disease to include a large group of consecutive patients and to use structured psychiatric interviews and standardized diagnostic criteria. Third, we have no pathological confirmation of our clinical diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease. However, the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association have been demonstrated to have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease. Moreover, all of our patients were assessed with either computerized tomography or MRI, and those with one or more stroke lesions were excluded from the study. Finally, the possibility of pseudodementia in some of our Alzheimer’s disease patients with depression needs to be discussed. In a longitudinal study that used the same diagnostic methods (25), the authors found that Alzheimer’s disease patients with depression at baseline who were no longer depressed at a follow-up evaluation 18 months later (N=20) had a similar rate of cognitive decline as Alzheimer’s disease patients with depression at baseline who were still depressed at follow-up (N=13). These findings argue against the possibility of pseudodementia in the present study.

One of the main findings of the study was that both minor and major depression had a significant psychopathological and functional impact on Alzheimer’s disease: both groups showed significantly more severe apathy, delusions, anxiety, pathological affective crying, irritability, deficits in activities of daily living, impairments in social functioning, and parkinsonism than Alzheimer’s disease patients without depression. These findings were not explained by differences in age, education, overall cognitive status, or severity of dementia. Major (but not minor) depressed Alzheimer’s disease patients had significantly more severe cognitive deficits than nondepressed Alzheimer’s disease patients, but this finding was of marginal significance. Whether depression produced significant functional impairment, or vice versa, or whether a common factor may increase the likelihood of both depression and functional impairment should be investigated in longitudinal studies.

Forsell and co-workers (25) suggested that depression may become more frequent as Alzheimer’s disease progresses from mild to moderate dementia and becomes less common in severe dementia. However, in the first study to address minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease in a systematic way, Lyketsos and co-workers (26) found no significant differences in the frequencies of major and minor depression among the stages of mild, moderate, and severe Alzheimer’s disease. In a recent study, Lopez and co-workers (27) found that major depression was less frequent in Alzheimer’s disease patients with severe cognitive deficits than in those with mild/moderate cognitive deficits. Our study demonstrated a similar frequency of major depression in the different stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and important methodological differences may explain this discrepancy. We classified patients into mild, moderate, or severe Alzheimer’s disease categories using the Clinical Dementia Rating, whereas Lopez and co-workers (27) graded the severity of cognitive deficits according to the MMSE. Their finding of a lower frequency of major depression in late Alzheimer’s disease conflicts with their findings of a similar frequency of depressed mood, suicidal ideation, low self-esteem, guilt, episodes of crying, and hopelessness between Alzheimer’s disease patients with mild and moderate/severe Alzheimer’s disease. They also found that sleep problems, anhedonia, and loss of energy were more frequent in patients with moderate/severe Alzheimer’s disease than in those with mild Alzheimer’s disease.

We followed the DSM-IV provision that depressed mood should be present most of the day, nearly every day, whereas the NIMH criteria do not require the presence of symptoms nearly every day (it is not clear whether this temporal qualification pertains to the symptom of depressed mood only or should also apply to the other symptoms of depression) (4). The rationale for this change is not clear, and loosening the temporal requirement may substantially decrease the reliability and specificity of the criteria. When patients were diagnosed with the NIMH criteria (i.e., depressed mood or loss of positive affect and at least three additional symptoms of depression), 41% of depressed patients in the stage of severe Alzheimer’s disease had no sad mood, suggesting that the NIMH criteria may have low specificity for depression in the late stages of dementia.

The question also arises as to whether a dimensional or a categorical strategy to diagnose depression should be used in Alzheimer’s disease. Studies of depression in the elderly have demonstrated that subsyndromal depressions might have an adverse functional impact that is sometimes undistinguishable from the negative effects of major depression (28). Our findings of more severe functional deficits in major depression compared to minor depression and in minor depression compared to no depression seems to fit a dimensional approach. The use of a dimensional strategy, such as establishing a cutoff score on a well-validated scale like the Hamilton depression scale, might detect subthreshold depression that may potentially benefit from early antidepressant treatment. We addressed this question by dividing our group of nondepressed patients into those who had a Hamilton depression scale score of 10 or more (N=41) and those who had Hamilton depression scale score of 9 or less (N=275). The patients with higher Hamilton depression scale scores had evidence of more severe delusional symptoms (Dementia Psychosis Scale—subthreshold depression score: mean=3.4, SD=3.7, versus euthymia score: mean=1.6, SD=3.7, respectively) (t=3.48, df=257, p<0.001), apathy (Apathy Scale score: mean=22.7, SD=8.2, versus mean=18.3, SD=9.4) (t=2.76, df=285, p<0.01), irritability (Irritability Scale score: mean=19.4, SD=8.1, versus mean=11.8, SD=8.3) (t=5.23, df=279, p<0.0001), and pathological affective crying (Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale score: mean=3.7, SD=4.0, versus mean=2.2, SD=4.0) (t=1.98, df=248, p<0.05). However, there were no significant differences between the two groups in activities of daily living or psychosocial adjustment, casting doubt about what is the functional impact of subthreshold depression defined with this dimensional approach.

Another relevant finding was that loss of interest was significantly more frequent among patients with either minor depression or major depression than in nondepressed patients, in contradiction to the NIMH consensus suggestion that loss of interest may not be specific for depression in Alzheimer’s disease. We did not assess decreased positive affect, which replaces the criterion of loss of interest in the NIMH criteria. However, the concept of “positive affect” may be difficult to assess in clinical practice unless clear guidelines are provided, and loss of positive affect could be confused with the blunted affect of apathy or with the loss of facial emotional expression typical of Alzheimer’s disease patients with parkinsonism. In addition, the NIMH criteria do not provide a clear definition of irritability, and this criterion may have low reliability. In a recent study that included 65 patients with Alzheimer’s disease who remitted from a depressive episode during a 3-month follow-up period (29), we found a significant improvement in all symptoms included in the DSM-IV clinical criteria for a major depressive episode. On the other hand, no improvement was found on scores for irritability, suggesting that depression and irritability are comorbid disorders in Alzheimer’s disease. Moreover, in a study that assessed 103 patients with Alzheimer’s disease using the Irritability Scale (14), we found no significant differences in the frequencies of major and minor depression between Alzheimer’s disease patients with and without irritability. In the present study, the patients with major depression or minor depression had significantly higher scores for irritability than nondepressed patients, but the association between irritability and sad mood was of marginal significance.

Finally, we found that patients with either major depression or minor depression had significantly higher scores on the Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale subscale for crying than nondepressed patients, demonstrating that affective lability is significantly associated with depression in Alzheimer’s disease. The NIMH criteria explicitly exclude affective lability, suggesting that this symptom would be better classified as “affective dysregulation because of dementia.” This suggestion is based on a study that found that the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia item rating “sudden changes in emotion” loaded on a factor of irritability/aggression but not on a factor of depressive features (30, 31). In a study that used a structured psychiatric interview and a valid instrument to rate the frequency and severity of affective lability in Alzheimer’s disease (18), we found that 25% of the sample had affective lability with crying episodes, and 81% of this group had either major or dysthymic depression compared to 30% for Alzheimer’s disease patients without affective lability. Important methodological differences may explain our discrepancies with the findings from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease. Its assessment of affective lability was based on responses to the item rating “sudden changes in emotion,” and its validity to rate affective lability has not been demonstrated (30, 31). Our findings suggest that affective lability is not only a frequent symptom in Alzheimer’s disease but may be a useful clinical marker of depression.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the DSM-IV criteria for major depression and minor depression identify clinically relevant syndromes of depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Future studies should demonstrate the long-term stability and predictive validity of major depression and minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as further explore the relationship of subsyndromal depression and functional impairment.

|

Received Aug. 5, 2004; revisions received Oct. 5 and Nov. 14, 2004; accepted Dec. 7, 2004. From the School of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences and Fremantle Hospital, University of Western Australia; the Department of and Psychiatry, University of Iowa, Iowa City; and the PET Center for Addiction and Mental Health, Clarke Division, Toronto. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Starkstein, Fremantle Hospital, Education Building T-7, Fremantle, 6959 Western Australia, Australia; [email protected] (e-mail). Partially supported by grants from the University of Western Australia, the Australian Rotary Health Research Fund, the Raine Medical Research Foundation, and the Fremantle Hospital Research Foundation. The authors thank Eran Chemerinski, M.D., Gustavo Petracca, M.D., Laura Garau, M.D., and Agustina Cao, M.A., for data collection; and Osvaldo Almeida, M.D., Ph.D., for comments on the manuscript.

Figure 1. Proportion of Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease Without a Sad Mood (N=262) or With a Sad Mood (N=316) Who Scored Positive on the SCID Criteria for Major Depression and for the Constructs of Apathy and Irritabilitya

aPatients without sad mood had a score of 1 (absent). Patients with sad mood had a score of 3. Results of the analyses were as follows: loss of interest (χ2=215.0, df=1, p<0.0001), poor concentration (χ2=139.1, df=1, p<0.0001), loss of energy (χ2=148.0, df=1, p<0.0001), insomnia (χ2=103.5, df=1, p<0.0001), guilt (χ2=97.0, df=1, p<0.0001), psychomotor retardation/agitation (χ2=69.4, df=1, p<0.0001), loss of weight (χ2=50.8, df=1, p<0.0001), apathy (χ2=19.4, df=1, p<0.0001), suicidal ideation (χ2=46.1, df=1, p<0.0001), and irritability (χ2=6.43, df=1, p<0.05).

1. Nyth AL, Gottfries CG: The clinical efficacy of citalopram in treatment of emotional disturbances in dementia disorders: a Nordic multicentre study. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:894–901Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Gallo JJ, Rabins PV, Anthony JC: Sadness in older persons: 13-year follow-up of a community sample in Baltimore, Maryland. Psychol Med 1999; 29:341–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Gallo JJ, Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG, Tien AY, Anthony JC: Depression without sadness: functional outcomes of nondysphoric depression in later life. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45:570–578Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Olin JT, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Schneider LS, Lebowitz BD: Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease: rationale and background. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 10:129–141Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Chemerinski E, Petracca G, Sabe L, Kremer J, Starkstein SE: The specificity of depressive symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:68–72Link, Google Scholar

7. Olin JT, Schneider LS, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Alexopoulos GS, Breitner JC, Bruce ML, Caine ED, Cummings JL, Devanand DP, Krishnan KR, Lyketsos CG, Lyness JM, Rabins PV, Reynolds CF III, Rovner BW, Steffens DC, Tariot PN, Lebowitz BD: Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 10:125–128Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hachinski VC, Lassen NA, Marshall J: Multi-infarct dementia: a cause of mental deterioration in the elderly. Lancet 1974; 2:207–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL: A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 140:566–572Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Starkstein SE, Migliorelli R, Manes F, Teson A, Petracca G, Chemerinski E, Sabe L, Leiguarda R: The prevalence and clinical correlates of apathy and irritability in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol 1995; 2:540–546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Starkstein SE, Petracca G, Chemerinski E, Kremer J: Syndromic validity of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:872–877Link, Google Scholar

16. Migliorelli R, Petracca G, Teson A, Sabe L, Leiguarda R, Starkstein SE: Neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological correlates of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol Med 1995; 25:505–513Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Starr LB, Robinson RG, Price TR: Reliability, validity, and clinical utility of the social functioning exam in the assessment of stroke patients. Exp Aging Res 1983; 9:101–106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Starkstein SE, Migliorelli R, Teson A, Petracca G, Chemerinsky E, Manes F, Leiguarda R: Prevalence and clinical correlates of pathological affective display in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1995; 59:55–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Kayton R: Guide for Use of the Uniform Data Set for Medical Rehabilitation. Buffalo, NY, Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation, 1986Google Scholar

20. Fahn S, Elton E: Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, in Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease. Edited by Fahn S, Marsden CD, Goldstein M, Calne CD. Florham Park, NJ, Macmillan, 1987, pp 153–163Google Scholar

21. Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S: The Boston Naming Test, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1983Google Scholar

22. De Renzi E, Faglini P: Development of a shortened version of the Token Test. Cortex 1978; 14:41–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Buschke H, Fuld PA: Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology 1974; 24:1019–1025Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Test Manual. New York, Psychological Corp, 1955Google Scholar

25. Forsell Y, Jorm AF, Fratiglioni L, Grut M, Winblad B: Application of DSM-III-R criteria for major depressive episode to elderly subjects with and without dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1199–1202Link, Google Scholar

26. Lyketsos CG, Steele C, Baker L, Galik E, Kopunek S, Steinberg M, Warren A: Major and minor depression in Alzheimer’s disease: prevalence and impact. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 9:556–561Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Lopez OL, Becker JT, Sweet RA, Klunk W, Kaufer DI, Saxton J, Habeych M, DeKosky ST: Psychiatric symptoms vary with the severity of dementia in probable Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003; 15:346–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Lyness JM, King DA, Cox C, Yoediono Z, Caine ED: The importance of subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients: prevalence and associated functional disability. J Am Geriatr Society 1999; 47:647–652Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Starkstein SE, Mizrahi R, Garau ML: The specificity of symptoms of depression in Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (in press)Google Scholar

30. Mack JL, Patterson MB, Tariot PN: Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia: development of test scales and presentation of data for 555 individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1999; 12:211–223Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Tariot PN, Mack JL, Patterson MB, Edland SD, Weiner MF, Fillenbaum G, Blazina L, Teri L, Rubin E, Mortimer JA, Stern Y (Behavioral Pathology Committee of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease): The Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1349–1357Link, Google Scholar