Effect of Olanzapine on Body Composition and Energy Expenditure in Adults With First-Episode Psychosis

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Weight gain is a commonly observed adverse effect of atypical antipsychotic medications, but associated changes in energy balance and body composition are not well defined. The authors report here the effect of olanzapine on body weight, body composition, resting energy expenditure, and substrate oxidation as well as leptin, insulin, glucose, and lipid levels in a group of outpatient volunteers with first-episode psychosis. METHOD: Nine adults (six men and three women) experiencing their first psychotic episode who had no previous history of antipsychotic drug therapy began a regimen of olanzapine and were studied within 7 weeks and approximately 12 weeks after olanzapine initiation. RESULTS: After approximately 12 weeks of olanzapine therapy, the median increase in body weight was 4.7 kg, a significant increase of 7.3% from first observation. Body fat, measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, increased significantly, with a propensity for central fat deposition. Lean body mass and bone mineral content did not change. Resting energy expenditure, measured by indirect calorimetry, did not change. Respiratory quotient significantly increased 0.12 with olanzapine and was greatest in those who gained >5% of their initial weight. Fasting insulin, C-peptide, and triglyceride levels significantly increased, but there were no changes in glucose levels; total, high density lipoprotein, or low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels; or leptin levels. CONCLUSIONS: Olanzapine appears to have induced an increase in central body fat deposition, insulin, and triglyceride levels, suggesting the possible development of insulin resistance. The decrease in fat oxidation may be secondary or predispose patients to olanzapine-induced weight gain.

Weight gain is a commonly observed adverse effect of antipsychotic drug therapy when administered to adolescents and adults for a variety of psychotic illnesses (1–5). While most conventional antipsychotics produce modest increases in weight (6), atypical antipsychotics—including clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine but not ziprasidone—are associated with more marked weight gain (7–9). Clinical trials of the efficacy and safety of the atypical antipsychotics show weight gain in 50%–80% of subjects, ranging from a few pounds to amounts that exceed 20% of baseline weight (3, 10, 11). Weight gain is a frequent cause of poor adherence to antipsychotic medications and a potential contributor to increased comorbidity (12), including glucose intolerance (13), diabetes mellitus (14, 15), and sleep apnea (16).

Significant weight gain is reportedly more common with clozapine and olanzapine than with other antipsychotic agents (2, 4, 7, 17). Predictors of weight gain in olanzapine-treated subjects versus a placebo control condition include increased appetite, good clinical response, and low baseline body mass index (9, 17, 18). These predictors are also consistent with observations from earlier studies that found an association between weight gain and good clinical response with typical antipsychotics (19) or low baseline body mass index (20, 21). Mechanistically, weight gain with olanzapine has been attributed to the combination of high affinities for 5-HT2C serotonin and H1 histamine receptors (22). Both serotonin and histamine are involved in the regulation of food intake and can affect the level of motor activity and caloric expenditure (23).

Despite an increased awareness of the metabolic hazards of atypical antipsychotics, many questions remain unanswered regarding the cause of weight gain induced by this group of medications and the mechanism by which it occurs. Theoretically, an atypical antipsychotic drug must trigger weight gain by inducing a positive energy balance. However, few human studies have systematically explored the effect of atypical antipsychotics on body composition and energy balance. Investigation into the impact of antipsychotic drugs on energy balance is complicated in clinical practice because most patients with psychosis have a history of multiple trials of a variety of antipsychotic medications. In addition, many patients are also being treated with multiple psychotropic medications for concomitant symptoms, and these medications (e.g., mood stabilizers and antidepressants) are frequently associated with weight gain.

One recent study of 10 inpatient adolescent male subjects treated with olanzapine found an increase in body mass index over a 4-week period (5). The increase in body mass index was attributed to increased caloric intake, assessed by direct measures of food consumption. There was no associated change in resting energy expenditure or physical activity. Although this short-term study of hospitalized adolescents suggested that the olanzapine-induced weight gain was due to an increase in food intake, longer-term studies in outpatient psychotic individuals are still needed. However, an accurate assessment of food intake in free-living individuals is challenging even in the absence of psychotic illnesses.

The ideal population to investigate causes of weight gain from atypical antipsychotics would be a cohort of first-episode antipsychotic-naive subjects to eliminate confounding effects of other medications. Here we investigated changes in body weight, body composition, and energy expenditure in nine outpatients with first-episode psychosis before, or shortly after, they began treatment with olanzapine and approximately 12 weeks after olanzapine initiation.

Method

Subjects

Adult patients who came to The University of North Carolina Hospitals or Dorothea Dix Psychiatric Hospital experiencing their first psychotic episode were asked to participate in an investigation of olanzapine-induced weight change. Inclusion criteria were 1) age 18–65 years, 2) DSM-IV criteria met for brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder, and 3) no other active illness. Subjects were excluded if they had a current comorbid alcohol or drug abuse diagnosis, were pregnant or lactating, or required treatment with medications other than lorazepam, clonazepam, zolpidem, benztropine, or propranolol for any medical or other psychiatric condition. All subjects gave written informed consent for participation in the study after the procedures were fully explained and questions answered. The UNC School of Medicine Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved the study protocol.

Study Protocol and Outcome Measures

At screening, all subjects were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV to determine psychiatric diagnosis and eligibility for this study. Additionally, demographic information, medical history, and a physical examination were performed to rule out medical illness. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale was used to assess psychiatric symptom severity. Subjects who, in the judgment of the treating clinician, required medications other than lorazepam, clonazepam, zolpidem, benztropine, or propranolol to control acute agitation or anxiety prior to completion of the baseline study visit were excluded from the study.

Within 14 days of screening, subjects were admitted for a 24-hour inpatient stay at the University of North Carolina General Clinical Research Center. At this first visit, subjects underwent assessment of their body weight, waist and hip measurements, body composition, resting energy expenditure, and respiratory quotient; fasting blood studies and a urine drug screen were also performed. Olanzapine, 5 mg/day, provided free of charge was titrated by the treating physician in 2.5-mg increments, and final doses ranged between 2.5–20 mg/day on the basis of clinical response. Dose changes were made no more frequently than once in a 24-hour period. Follow-up visits to the psychiatry outpatient department of the UNC Neurosciences Hospital, the clinical research unit of Dorothea Dix Hospital, or the outpatient General Clinical Research Center occurred at weekly intervals for two visits, then biweekly for five visits. At these visits, assessments of adverse events, medication use, weight, and capillary glucose were obtained. The final study visit was conducted at the General Clinical Research Center during a 24-hour inpatient stay after the subject completed 12 weeks of olanzapine treatment. Two subjects ended the study prematurely, one at 7 weeks and the other at 10 weeks. The median time receiving treatment at last visit was 88 days (range=48–111). In addition to the aforementioned outpatient assessments, body composition, metabolic rate, and blood work were performed at this visit.

Body weight was measured with subjects wearing light clothing; a digital scale that was calibrated monthly was used. Subjects had measurements taken upon awakening during their first and last visits, and at variable times of day during follow-up outpatient visits. Height was assessed at first visit and last visit by a wall-mounted stadiometer. Waist circumference was measured at the umbilicus and hip measurement at the fullest part of the hip. Body composition (fat mass, fat-free soft tissue mass, and bone mineral content) was assessed by using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry with a Delphi-W instrument (Hologic, Inc., Waltham, Mass.) at the first visit and last visit (approximately 12 weeks). Substrate utilization (respiratory quotient) and resting energy expenditure were determined by indirect calorimetry with a CPX/D MedGraphics Metabolic Cart (St. Paul, Minn.) at least 2 hours postprandial and after at least 30 minutes in the supine resting position. Measures of oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production were taken at 30-second intervals over 20 minutes under standard temperature, pressure, and humidity. Resting energy expenditure was calculated using Weir’s formula (24).

Standard laboratory methods were used to determine 1) basic chemistries; 2) fasting levels of glucose, insulin, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides; and 3) levels of C-peptide and prolactin. Low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was determined by the Friedewald et al. calculation (25): LDL=total cholesterol – (HDL + [triglycerides/5]). Leptin was measured by using the Linco human ultrasensitive radioimmunoassay kit (St. Charles, Mo.). All laboratory measurements were obtained at first visit and last visit (approximately 12 weeks apart).

Data Analysis

The study’s main outcome measures were change in body weight, body composition, energy expenditure, and respiratory quotient after 12 weeks of treatment with olanzapine. For all outcomes, change was computed as the difference from first to last observation. Due to the skewed distribution of outcome variables and small sample size, nonparametric testing procedures were used. As a result, median changes are reported instead of mean changes. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to test whether outcome measures at last observation were significantly different from initial observation. Spearman rank correlations were used to assess association between changes in outcome variables from first to last observation. Exploratory data analyses were also performed on related variables and laboratory measures. Computations were performed using SAS (26).

Results

Subjects

Nine individuals (six men and three women; Caucasian: N=7; African American: N=1; Hispanic: N=1) with a median age of 21.5 years (range=20.8–27.3) were included in the analysis. Seven subjects were high school graduates, and five had some college education. Four subjects were antipsychotic naive at the time of their first visit. Three had been receiving olanzapine for less than 1 week at study entry; the other two subjects had been receiving olanzapine for 5 weeks and 7 weeks. Two subjects dropped out early because of weight gain—one at 7 weeks and one at 10 weeks; both patients’ last visits were used in the analysis. No subject had an admission to the hospital that was unrelated to the study protocol.

Body Weight and Composition

Body weight and body mass index increased significantly with olanzapine therapy (Table 1). The median increase in weight was 4.7 kg, or 7.3% of initial weight. At the time of first observation, six volunteers were of normal body mass index (19–24.9 kg/m2), and three were overweight (25–29 kg/m2). One subject went from a body mass index in the lean range to a body mass index in the overweight range, 20.8 to 25.1 kg/m2. No subject gained an amount of weight to be classified as obese (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2). Compared with their usual weight, four subjects reported a history of recent weight loss prior to entry into the study. However, there was no qualitative relationship between weight loss before study entry and weight gain with olanzapine. One of the two subjects who did not gain more than 5% weight had a positive cocaine drug screen and was nonadherent with olanzapine therapy during the study period. The other was receiving a small dose of olanzapine, 2.5 mg/day. Body fat percentage and absolute fat mass increased significantly with olanzapine treatment (Table 1). The significant median increase in the waist-to-hip ratio suggested central deposition of body fat. There was no significant change in lean body mass or bone mineral content. Blood pressure did not change significantly in the study group.

Energy Expenditure and Respiratory Quotient

Absolute 24-hour resting energy expenditure and resting energy expenditure normalized to lean body mass did not change with olanzapine (Table 1). There was no evidence of lower baseline resting energy expenditure in subjects who gained the most amount of weight. Notably, respiratory quotient increased significantly with olanzapine treatment (Table 1). The median change in respiratory quotient was 0.12, a 14% increase. There was a significant positive correlation between change in respiratory quotient and change in weight (r=0.73, df=7, p<0.03).

Laboratory Values

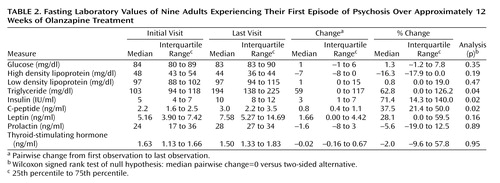

Fasting insulin levels and C-peptide levels increased significantly (Table 2). The increase in insulin occurred in all but one subject. Fasting glucose levels did not change significantly. The median change in fasting triglyceride levels with olanzapine was significant: 59 mg/dl (an increase of 63% from initial visit), but there was no significant change in high density lipoproteins, low density lipoproteins, or total cholesterol. Median leptin levels did not change. Further, there was no relationship between change in leptin levels and change in body fat or body weight. Prolactin and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels also did not change with olanzapine treatment. The absence of a significant change in prolactin levels is consistent with other studies that have reported minimal effects of olanzapine on prolactin levels compared with haloperidol and risperidone (27).

Discussion

The results of this olanzapine study are consistent with other studies that have demonstrated significant weight gain in psychotic patients treated with this class of drugs. The weight gain in this study occurred in all but two subjects. One volunteer was nonadherent to olanzapine treatment, and the results of a urine drug screen revealed the presence of cocaine, an appetite suppressant (28). The other subject was receiving a low dose of olanzapine (2.5 mg/day); all others were receiving at least 5 mg/day. Although suggestive, this study is too small to determine if there is an association between weight gain and drug dose (or at least a threshold dose above which weight gain can occur). Other studies have attributed the weight gain to the fact that patients were returning to their premorbid weight. We did not find that subjects with self-reported weight loss before study entry, or subjects with the lowest body mass index, were any more prone to weight gain than subjects who were near their usual or peak adult weight. However, we did not confirm whether these self-reported weights were accurate. It is encouraging to know that no subject became obese in this study, but the study was of limited duration. Other studies have described a pattern of weight gain that extends beyond 6 months of olanzapine therapy (17). We observed no clear evidence that the weight gain was tapering off after 12 weeks of treatment.

This study demonstrated by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry that the weight gain was primarily due to an increase in body fat, which amounted to about 74% of the total weight gain. Furthermore, the increase in the waist-to-hip ratio suggests a central fat deposition, a pattern associated with adverse metabolic consequences (29). The increase in body fat also indicates that the weight gain was not due to fluid accumulation, as is seen in treatment of diabetics with thiazolidinediones (30). The most likely explanation for the fat gain is that subjects maintained positive energy balance and deposited this energy in the form of triglyceride in adipose tissue. From the amount of weight gain over the 12-week study period, we would have had to detect a 475 kcal/day increase in caloric intake, assuming energy expenditure did not change. In this small sample, we did not have the power to detect such a change. In addition, long-term assessment of caloric intake has multiple limitations. For example, studies using doubly labeled water to measure 24-hour expenditure have determined that obese subjects underreport caloric intake by up to 40% and overreport physical activity (31). Similar validation studies have not been reported in psychotic patients, who often have at least mild cognitive impairment as part of their illness. Validated measurements of food intake, based on 24-hour energy expenditure, were not performed in the current study because doubly labeled water was unavailable during the study period.

It is possible that the olanzapine-induced weight gain was due to a decrease in energy expenditure. We did not see a change in absolute resting energy expenditure or resting energy expenditure normalized to lean body mass. Therefore, a decrease in resting energy expenditure is not a viable explanation for olanzapine-induced weight gain. The most variable portion of energy expenditure is physical activity. Studies in 5-HT2C receptor knockout mice with late-onset obesity show leptin-independent hyperphagia and hyperactivity but reduced energy cost of physical activity (25, 32). If the animal studies translate to humans, then it is possible that inhibition of this receptor subtype by olanzapine may produce similar changes in energy balances to increase body fat. In this study, efforts were made to assess physical activity with an accelerometer, but interpretation of the data was problematic, since several subjects removed the device during waking hours. However, there were no reported complaints of sedation to suggest that the weight gain was due to lack of spontaneous activity.

This study suggests that olanzapine induced a decrease in fatty acid oxidation. Decreased fatty acid oxidation has been associated with weight gain (33). One group reported that in a study of Pima Indians, high respiratory quotient/low fatty acid oxidation was a predictor of weight gain over the long-term (34). The decision to use fatty acids or carbohydrates as fuels is highly regulated and depends on numerous exogenous and endogenous factors, including the level of feeding (positive versus negative energy balance), the composition of food eaten (high versus low carbohydrate), the size of the glycogen stores, and the amount of adipose tissue as well as genetic factors (reviewed in reference 35). In this study, we cannot determine precisely how olanzapine induced the shift in nutrient utilization away from fatty acids toward carbohydrates, but the increase in body fat and triglyceride and insulin levels may be a reflection of this process

Leptin is an adipocyte-derived negative regulator of food intake (36) that increases with adiposity (37). Low plasma leptin concentrations have been shown to predict weight gain in some studies (38) but not all (39–41). One group reported a significant mean increase in leptin levels in olanzapine-treated inpatients over a 4-week period (from 6.1 [SD=6] to 10.1 [SD=5.4]) (42). Another group found an inverse relationship between clozapine-induced increase in circulating leptin at 2 weeks and weight gain at 6 and 8 months. Here, levels of leptin were similar to those reported in the study of Kraus et al. (42). Additionally, we detected a tendency for leptin levels to increase, but the median change with olanzapine treatment was not significant. Unlike Monteleone et al. (43), we did not find an inverse relationship between baseline leptin levels and weight gain. This difference between our studies may be drug related, i.e., olanzapine versus clozapine. Alternatively, we compared pretreatment leptin levels to weight gain at 12 weeks, whereas they compared leptin levels after 2 weeks with weight gain at 6 months.

Atypical antipsychotics have been found to induce impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes, and diabetic ketoacidosis (13–15). In this study, no subject developed diabetes, but the increases in insulin and C-peptide levels were consistent with a possible decrease in insulin sensitivity. The tendency for high density lipoprotein levels to decrease and the significant increase in triglyceride levels are also consistent with the development of insulin resistance. One recent study demonstrated a decrease in insulin sensitivity in healthy volunteers treated with olanzapine or risperidone for 15–17 days (44). However, these changes in insulin were thought to be secondary to the drug-induced weight gain. The small study group size and uncontrolled study design limit our ability to define the mechanistic pathways that led to the drug-associated weight gain and changes in glucose and lipid metabolism.

In conclusion, this study indicates that after approximately 12 weeks of olanzapine therapy, there is a significant increase in weight, increase in central adiposity, and decrease in fat oxidation. In addition, the laboratory changes are consistent with a decrease in insulin sensitivity that could lead to the development of insulin resistance syndrome. However, the size and design of the study limit the interpretation of these results. Future studies are warranted to confirm these findings, determine if these changes occur across the class of atypical antipsychotics, and determine the mechanistic basis of these clinical effects and their potential for contributing to the development of comorbid illnesses.

|

|

Received March 3, 2003; revision received Feb. 27, 2004; accepted Feb. 29, 2004. From the Departments of Psychiatry, Biostatistics, and Nutrition, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Harp, Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina, CB Number 7461, McGavran-Greenberg Hall, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK-56350) to the University of North Carolina Clinical Nutrition Research Unit; an NIH grant (RR-00046) to the University of North Carolina Schizophrenia Research Center; and an NIMH grant (MH-064065) to the Silvio O. Conte Center for the Neuroscience of Mental Disorders. This project also was supported by the Foundation of Hope of Raleigh North Carolina and an unrestricted gift from Eli Lilly and Company. The authors thank Marjorie Busby, Steffen Baumann, and Patricia S. Judd of the General Clinical Research Center Body Composition Lab for their work on this project.

1. Ratzoni G, Gothelf D, Brand-Gothelf A, Reidman J, Kikinzon L, Gal G, Phillip M, Apter A, Weizman R: Weight gain associated with olanzapine and risperidone in adolescent patients: a comparative prospective study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:337–343Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Tollefson GD, Beasley CM Jr, Tran PV, Street JS, Krueger JA, Tamura RN, Graffeo KA, Thieme ME: Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders: results of an international collaborative trial. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:457–465Link, Google Scholar

3. Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, Chandler LP, Cappelleri JC, Infante MC, Weiden PJ: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1686–1696Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Allison DB, Casey DE: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a review of the literature. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:22–31Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Gothelf D, Falk B, Singer P, Kairi M, Phillip M, Zigel L, Poraz I, Frishman S, Constantini N, Zalsman G, Weizman A, Apter A: Weight gain associated with increased food intake and low habitual activity levels in male adolescent schizophrenic inpatients treated with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1055–1057Link, Google Scholar

6. Klett CJ, Caffey EM: Weight changes during treatment with phenothiazine derivatives. J Neuropsychiatry 1960; 2:102–108Medline, Google Scholar

7. Tran PV, Tollefson GD, Sanger TM, Lu Y, Berg PH, Beasley CM Jr: Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of schizoaffective disorder: acute and long-term therapy. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:15–22Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KNR, Daniel DG, Petty F, Centorrino F, Wang R, Grundy SL, Greaney MG, Jacobs TG, David SR, Toma V (Olanzapine HGEH Study Group): Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:702–709Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Basson BR, Kinon BJ, Taylor CC, Szymanski KA, Gilmore JA, Tollefson GD: Factors influencing acute weight change in patients with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine, haloperidol, or risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:231–238Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Briffa D, Meehan T: Weight changes during clozapine treatment. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1998; 32:718–721Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Heo M, Mentore JL, Cappelleri JC, Chandler LP, Weiden PJ, Cheskin LJ: The distribution of body mass index among individuals with and without schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:215–220Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wirshing DA: Adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:7–10Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hedenmalm K, Hagg S, Stahl M, Mortimer O, Spigset O: Glucose intolerance with atypical antipsychotics. Drug Saf 2002; 25:1107–1116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Popli AP, Konicki PE, Jurjus GJ, Fuller MA, Jaskiw GE: Clozapine and associated diabetes mellitus. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:108–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hagg S, Joelsson L, Mjorndal T, Spigset O, Oja G, Dahlqvist R: Prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in patients treated with clozapine compared with patients treated with conventional depot neuroleptic medications. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:294–299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wirshing DA, Pierre JM, Wirshing WC: Sleep apnea associated with antipsychotic-induced obesity. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:369–370Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kinon BJ, Basson BR, Gilmore JA, Tollefson GD: Long-term olanzapine treatment: weight change and weight-related health factors in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:92–100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Jones B, Basson BR, Walker DJ, Crawford AM, Kinon BJ: Weight change and atypical antipsychotic treatment in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 2):41–44Google Scholar

19. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC, Kando J, Centorrino F: Clozapine and body mass change. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 43:520–524Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hummer M, Kemmler G, Kurz M, Kurzthaler I, Oberbauer H, Fleischhacker WW: Weight gain induced by clozapine. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1995; 5:437–440Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Umbricht DS, Wirshing WC, Wirshing DA, McMeniman M, Schooler NR, Marder SR, Kane JM: Clinical predictors of response to clozapine treatment in ambulatory patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:420–424Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Schmidt AW, Lebel LA, Howard J, Harry R., Zorn SH: Ziprasidone: a novel antipsychotic agent with a unique human receptor binding profile. Eur J Pharmacol 2001; 425:197–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Nonogaki K, Abdallah L, Goulding EH, Bonasera SJ, Tecott LH: Hyperactivity and reduced energy cost of physical activity in serotonin 5-HT2C receptor mutant mice. Diabetes 2003; 52:315–320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Weir JBD: New methods for calculation of metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J Physiol (London) 1949; 109:1–9Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972; 18:499–502Medline, Google Scholar

26. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, version 8. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1999Google Scholar

27. David SR, Taylor CC, Kinon BJ, Breier A: The effects of olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on plasma prolactin levels in patients with schizophrenia. Clin Ther 2000; 22:1085–1096Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Gold MS (ed): Cocaine (and Crack): Clinical Aspects. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1992Google Scholar

29. Krotkiewski M, Björntorp P, Sjostrom L, Smith U: Impact of obesity on metabolism in men and women: importance of regional adipose tissue distribution. J Clin Invest 1983; 72:1150–1162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Wang F, Aleksunes LM, Reagan LA, Vergara CM: Management of rosiglitazone-induced edema: two case reports and a review of the literature. Diabetes Technol Ther 2002; 4:505–514Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Lichtman SW, Pisarska K, Berman ER, Pestone M, Dowling H, Offenbacher E, Weisel H, Heshka S, Matthews DE, Heymsfield SB: Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. N Engl J Med 1992; 327:1893–1898Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Nonogaki K, Strack AM, Dallman MF, Tecott LH: Leptin-independent hyperphagia and type 2 diabetes in mice with a mutated serotonin 5-HT2C receptor gene. Nat Med 1998; 4:1124–1125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Filozof CM, Murua C, Sanchez MP, Brailovsky C, Perman M, Gonzalez CD, Ravussin E: Low plasma leptin concentration and low rates of fat oxidation in weight-stable post-obese subjects. Obes Res 2000; 8:205–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Zurlo F, Lillioja S, Esposito-Del Puente A, Nyomba BL, Raz I, Saad MF, Swinburn BA, Knowler WC, Bogardus C, Ravussin E: Low ratio of fat to carbohydrate oxidation as a predictor of body weight gain: study of 24h RQ. Am J Physiol 1990; 259:E650-E657Google Scholar

35. Schutz Y: Abnormalities of fuel utilization as predisposing to the development of obesity in humans. Obes Res 1995; 3(suppl 2):173S-178SGoogle Scholar

36. Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P: Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science 1995; 269:546–549Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Considine RV, Considine EL, Williams CJ, Nyce MR, Magosin SA, Bauer TL, Rosato EL, Colberg J, Caro JF: Evidence against either a premature stop codon or the absence of obese gene mRNA in human obesity. J Clin Invest 1995; 95:2986–2988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Lindroos AK, Lissner L, Carlsson B, Carlsson LM, Torgerson J, Karlsson C, Stenlof K, Sjostrom L: Familial predisposition for obesity may modify the predictive value of serum leptin concentrations for long-term weight change in obese women. Am J Clin Nutr 1998; 67:1119–1123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Haffner SM, Mykkanen LA, Gonzalez CC, Stern MP: Leptin concentrations do not predict weight gain: the Mexico City Diabetes Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998; 22:695–699Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Hodge AM, de Courten MP, Dowse GK, Zimmet PZ, Collier GR, Gareeboo H, Chitson P, Fareed D, Hemraj F, Alberti KG, Tuomilehto J (Mauritius Noncommunicable Disease Study Group): Do leptin levels predict weight gain?—a 5-year follow-up study in Mauritius. Obes Res 1998; 6:319–325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Lissner L, Karlsson C, Lindroos AK, Sjostrom L, Carlsson B, Carlsson L, Bengtsson C: Birth weight, adulthood BMI, and subsequent weight gain in relation to leptin levels in Swedish women. Obes Res 1999; 7:150–154Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Kraus T, Haack M, Schuld A, Hinze-Selch D, Kühn M, Uhr M, Pollmächer T: Body weight and leptin plasma levels during treatment with antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:312–314Abstract, Google Scholar

43. Monteleone P, Fabrazzo M, Tortorella A, La Pia S, Maj M: Pronounced early increase in circulating leptin predicts a lower weight gain during clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 22:424–426Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Sowell MO, Mukhopadhyay N, Cavazzoni P, Shankar S, Steinberg HO, Breier A, Beasley CM Jr, Dananberg J: Hyperglycemic clamp assessment of insulin secretory responses in normal subjects treated with olanzapine, risperidone, or placebo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87:2918–2923Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar