The Interrelationship of Neuroticism, Sex, and Stressful Life Events in the Prediction of Episodes of Major Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Three potent risk factors for major depression are female sex, the personality trait of neuroticism, and adversity resulting from exposure to stressful life events. Little is known about how they interrelate in the etiology of depressive illness. METHOD: In over 7,500 individual twins from a population-based sample, the authors used a Cox proportional hazard model to predict onsets of episodes of DSM-III-R major depression in the year before the latest interviews on the basis of previously assessed neuroticism, sex, and adversity during the past year; adversity was operationalized as the long-term contextual threat scored from 15 life event categories. RESULTS: In the best-fit Cox model for prediction of depressive onsets, neuroticism, female sex, and greater adversity all strongly increased risk for major depression. An interaction was seen between neuroticism and adversity such that individuals with high neuroticism were at greater overall risk for major depression and were more sensitive to the depressogenic effects of adversity. An interaction was also seen between adversity and sex, as the excess risk for major depression in women was confined to individuals with low stress exposure. CONCLUSIONS: Psychosocial adversity interacts both with neuroticism and with sex in the etiology of major depression. The impact of neuroticism on illness risk is greater at high than at low levels of adversity, while the effect of sex on probability of onset is the opposite—greater at low than at high levels of stress. Complete etiologic models for major depression should incorporate interactions between risk factor classes.

In building comprehensive models for the causes of psychiatric disorders, we must confront the question of how distinct risk factors interact in the etiology of illness. Most interest has focused on two models: additive and multiplicative (1). In this article, we evaluate these models for the impact on liability to major depression of three potent risk factors: the personality trait of neuroticism (2), sex (3), and psychosocial adversity, operationalized by measures of recent stressful life events (4, 5).

In evaluating neuroticism and adversity, the additive model assumes that the impact of adversity on risk of illness is independent of the level of neuroticism. By contrast, the positive multiplicative model suggests that the impact of adversity on risk of illness increases with higher levels of neuroticism. The multiplicative model predicts that a high neuroticism level affects the probability of depressive illness both by increasing overall risk of illness and by increasing susceptibility to the depressogenic effects of adversity.

Neuroticism was initially designed to measure emotionality (2) and has been identified as a major personality dimension by nearly all subsequent investigators (6). In adulthood, neuroticism is stable over time (7, 8); high levels are associated with risk for major depression both cross-sectionally (9–11) and prospectively (7, 12, 13). Genetic risk factors for neuroticism and major depression are closely related (7, 14).

The relationship between stressful life events and risk of onset of major depression has been repeatedly demonstrated (5) and is likely to be largely causal (15). In this study, we used as our measure of adversity the level of long-term contextual threat associated with individual stressful life events (16). The level of threat posed by a life event is strongly related to the risk of subsequent depressive onsets (16, 17).

Several studies have previously explored sex differences in the sensitivity to the depressogenic effects of stressful life events, with mixed results (18). However, to our knowledge, all prior studies have examined sex differences in the reaction to the presence versus absence of stressful life events rather than to the level of threat posed thereby.

Method

Sample

The twins in this study derive from the population-based Virginia Twin Registry (19), which now constitutes part of the Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry. Female-female twin pairs, from birth years 1934 to 1974, became eligible if both members previously responded to a mailed questionnaire in 1987–1988, the response rate to which was approximately 64%. They have been approached for four subsequent waves of personal interviews from 1988 to 1997, with cooperation rates ranging from 85% to 92%. The male-male and male-female twin pairs, covering the birth years 1940–1974, were ascertained in a separate study—with an initial cooperation rate of 72%—and have been approached for two waves of interviews from 1993 to 1998. After explanation of the research protocol, signed informed consent statements were obtained before all face-to-face interviews, and oral consent was obtained before all telephone interviews.

Measures

During each interview wave, we assessed the occurrence over the last year of 14 individual symptoms that represented the disaggregated nine A criteria for major depression in DSM-III-R (e.g., two items for criterion A4 to assess separately insomnia and hypersomnia). For each reported symptom, interviewers probed to ensure that it was due neither to physical illness nor to medication. The respondents and interviewers then aggregated symptoms reported for the last year into co-occurring syndromes. If depressive syndromes occurred, the respondents were asked when each one occurred and the months of its onset and offset. To be eligible for the occurrence of a new depressive episode, the respondent had to report being basically symptom free and “back to his/her normal self” for at least 2 weeks. The diagnosis of major depression was made by a computer algorithm incorporating the DSM-III-R criteria, except criterion B2 (which excludes “uncomplicated bereavement”). In 375 twins interviewed twice by different interviewers with a mean interinterview interval of 30 days (SD=9), the interinterview reliability of the diagnosis of major depression in the last year was good: the kappa (20) value was 0.68, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.57–0.80, and the tetrachoric correlation coefficient was 0.92, with a 95% CI of 0.86–0.98.

Neuroticism was measured by using the 12-item scale from the shortened Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (21). Three representative items for this scale were 1) “Are you the type of person whose feelings are easily hurt?”; 2) “Are you the type of person who is rather nervous?”; and 3) “Are you the type of person who is a worrier?” In this study, we took the levels of neuroticism reported from wave 1 of both the female-female and the male-male and male-female samples. Our interviews assessed the occurrence, to the nearest month, of 11 “personal” stressful life events (events occurring primarily to the informant): “assault” (assault, rape, or mugging), “divorce/separation” (divorce, marital separation, broken engagement, or breakup of other romantic relationship), “major financial problem,” “serious housing problems,” “serious illness or injury,” “job loss” (laid off from a job or fired), “legal problems” (trouble with police or other legal trouble), “loss of confidant” (separation from other loved one or close friend other than a spouse or partner), “serious marital problems,” (involving a marital or marriage-like intimate, cohabiting relationship), “robbed,” and “serious difficulties at work.” We also assessed four classes of network events, meaning events that occurred primarily to, or in interaction with, an individual in the respondent’s social network. Network was here defined as spouse, child, parent, sibling, other close relative, or “someone else close to you.” These event classes consisted of 1) “getting along with”—serious trouble getting along with an individual in the network, 2) “crisis”—a serious personal crisis of someone in the network, 3) “death”—death of an individual in the network, and 4) “illness”—serious illness of someone in the network.

Each reported stressful life event in waves 3 and 4 of the female-female sample and wave 2 of the male-male and male-female sample was rated by the interviewer on the level of long-term contextual threat. “Long-term” was defined as persisting at least 10–14 days after the event. Following the practice of Brown, we instructed our interviewers to rate “what most people would be expected to feel about an event in a particular set of circumstances and biography, taking no account either of what the respondent says about his or her reaction or about any psychiatric or physical symptoms that followed it” (22, p. 24).

Long-term contextual threat was rated on a 4-point scale: minor, low moderate, high moderate, and severe (22). The reliability of our ratings was determined by interrater and test-retest designs. Interrater reliability was assessed by having experienced interviewers review tape recordings of the interview sections in which 92 randomly selected individual stressful life events were evaluated. Test-retest reliability was obtained by repeating the interview with 191 respondents at a mean interval of 4 weeks. We obtained 173 scored life events that appeared to be consistent in the two interviews; the subject described the event similarly in both interviews and placed it in the same 1-month period. We assessed reliability by Spearman correlation (rs) and weighted kappa (23). The test-retest reliability for long-term contextual threat was rs=0.60 and kappa=0.41, while the interrater reliability was rs=0.69 and kappa=0.67.

Statistical Methods

Person-months were used as the unit of analysis, and the analyses were conducted with a Cox proportional hazards model operationalized in the SAS procedure PHREG (24, 25). Three predictor variables were used: neuroticism, sex, and long-term contextual threat. When multiple events occurred in the same month, long-term contextual threat was coded as the highest threat level of any recorded event. The dependent variable was the onset of a depressive episode.

The final model was developed on the basis of nine strata. Each stratum consisted of data for subjects who had a specific number of prior onsets and participated in one interview wave—specifically zero, one, or two prior onsets in the past 13 months for subjects from the three included waves. There were too few subjects with three or more onsets to include such data. This stratification is a conservative way to deal with within-subject correlation. An 18-strata model was also developed in which twins were randomly assigned to two separate groups to conservatively evaluate the impact of familial correlations. Coding was done on the basis of the “conditional A” model proposed by Hosmer and Lemeshow (26).

Neuroticism was standardized to have a mean score of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, allowing easy interpretation and a meaningful quadratic term. Long-term contextual threat was coded so that 0 meant no stressful life event during the month and 1 through 4 meant the occurrence of a stressful life event with minor, low moderate, high moderate, or severe long-term contextual threat. To incorporate the ordinal structure and simplify interpretation of the interaction, long-term contextual threat was coded as follows: four dummy variables X1, X2, X3, and X4 were used. If there was no stressful life event, all four were coded as 0. If there was a significant life event with a threat scored as at least 1, X1 was coded as 1. If the threat was scored as at least 2, X2 was also coded as 1. If the threat was scored as at least 3, then X3 was coded as 1. For an event with a threat level scored as 4, all four dummy variables were coded as 1. Thus, the coding for a month with an event with a long-term contextual threat scored as 2 was as follows: X1=1, X2=1, X3=0, X4=0. This method of dummy variable coding is often referred to as “thermometer coding” (27). Finally, the dummy variables were incorporated as a time-dependent covariate with a linear decay that abated after 3 months. The final model was found by starting with all three-way interactions and eliminating nonsignificant terms.

In these analyses, the dependent variable—a depressive episode—was dichotomous, and this fact introduced unavoidable complexity into our analyses. We were interested in clarifying the nature of the interaction between personality and adversity, and from a statistical perspective, any interaction is scale dependent. A Cox regression model has advantages in these analyses. However, instead of predicting the probability of outcome p, the model predicts a logarithmic transformation of p. Because the dependent variable is a logarithmic function, the nature of what an interaction means changes. What is a multiplicative interaction in the raw probability model becomes additive in the Cox model, while what is additive in the raw probability model becomes a negative interaction in the Cox model. Because a Cox model formally tests deviations from a multiplicative relationship between neuroticism and adversity in the prediction of depressive onsets, we also developed and applied a model that formally tests deviations from an additive relationship.

Information for these analyses came from a total of 7,517 individuals who participated in waves 3 and 4 of the female-female sample and wave 2 of the male-male and male-female sample. These individuals reported a total of 1,194 onsets of major depression and 10,381 periods of observation; each period of observation began either at the start of a 1-year prevalence window or at the time of recovery from an episode and ended either at the conclusion of that 1-year window or at the time of an onset of a depressive episode. The number of these onsets that occurred with zero, one, and two prior episodes in the 13-month time period were, respectively, 771 (64.6%), 276 (23.1%), and 147 (12.3%).

The final Cox model was achieved in the following way. We started with a model consisting of 29 terms: the four long-term contextual threat indicator variables, sex, the neuroticism score, the square of the neuroticism score, and all two- and three-way interactions between them. Nonsignificant terms (i.e., p>0.05) were removed one at a time, and then the model was rerun. After 20 eliminations, the final model, which has nine terms, was reached. We repeated the elimination process, beginning with several other arbitrarily chosen terms to verify that the resulting nine-term model was the only all-significant term subset of the full 29-term model.

For our additive relative hazard model, we used the computer program R (28) with a modified version of Fekjaer and Aalen’s implementation (http://www.med.uio.no/imb/stat/addreg/) of Aalen’s model (29).

Results

The best-fit nine-strata Cox model for predicting the onset of major depression is depicted in Table 1 and includes strong and highly significant main effects for neuroticism, sex, and the four levels of adversity. Each increase of a standard deviation in the neuroticism score carries a hazard ratio for a depressive onset of 1.72. Compared to men, women have a hazard ratio for a depressive onset of 2.09. Each increasing level of long-term contextual threat carries additional risk for a depressive onset, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.41 to 2.36. Since these ratios multiply, it can be calculated that the hazard ratio associated with a multiple stressful life event with a long-term contextual threat rating of 1, 2, 3, or 4, respectively, equals 1.41, 3.33, 6.69, or 15.78, respectively.

In addition to these main effects, the final model contains one quadratic term and two negative interactions. The quadratic term is for neuroticism and is modest both in terms of the effect size and the significance, and it indicates that, at high levels of neuroticism, the effect of neuroticism on risk for major depression is slightly less than that predicted by a purely linear effect. The first interaction, also modest in size and significance, is between neuroticism and ratings of long-term contextual threat of 3 or higher. This term suggests that at high levels of long-term contextual threat, the relationship between neuroticism and adversity becomes slightly less than multiplicative. The second interaction is between sex and ratings of long-term contextual threat of 2 or higher and is, by contrast, both large in effect and statistically robust. Indeed, the magnitude of this interaction term is nearly as great as the main effect for sex. The model predicts that in those exposed to either no stressful life events or a stressful life event with minor long-term contextual threat, women are at substantially higher risk than men (hazard ratio=e0.74=2.09). However, in those exposed to higher levels of long-term contextual threat, the excess risk for women is negligible (hazard ratio=e(0.74–0.68)=1.06).

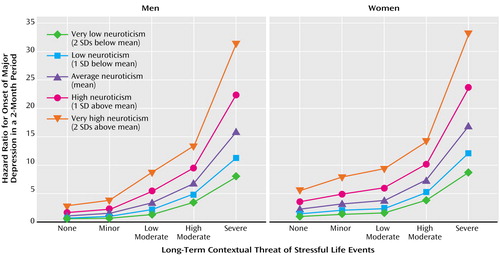

The predictions of the best-fit model are illustrated, separately for men and women, in Figure 1. We assigned, as a point of reference, a hazard ratio of unity to a man with a mean level of neuroticism and an adversity level of 0 (that is, no exposure to any stressful life event). The predicted curves for five possible levels of neuroticism are depicted.

Three main points are of interest. First, within every level of long-term contextual threat, higher levels of neuroticism predict increasing risk for major depression. Second, the impact of neuroticism on the risk for major depression is much greater in those exposed to high levels of long-term contextual threat. That is, the curves for the various levels of neuroticism splay out with increasing levels of adversity. Third, at every level of neuroticism and every level of adversity, the risk is higher in women than in men. However, high female-to-male ratios (>2.0) are found only with low levels of adversity. The female-male hazard ratio for major depression is much lower at high levels of adversity, regardless of the level of neuroticism.

We also ran these analyses with our 18-strata model correcting for correlated observations within twin pairs. The results were similar, with seven of the nine regression coefficients within 0.01 of those found with the nine-strata model (Table 1). Finally, we fit the data to our additive model, finding significant main effects for neuroticism, all four levels of long-term contextual threat, and sex as well as a significant negative interaction between sex and long-term contextual threat ratings of 3 or higher (details on request). Of most interest, however, we found evidence for highly significant positive interactions between neuroticism and long-term contextual threat ratings of 1 or higher (z=3.68, p<0.001) and between neuroticism and long-term contextual threat ratings of 3 or 4 (z=3.89, p<0.001).

Discussion

We sought in this study to clarify how the personality trait of neuroticism, sex, and adversity—operationalized as the level of long-term contextual threat posed by recent stressful life events—interacted in the etiology of major depression. Our two a priori models postulated either that neuroticism and adversity added together in the impact on liability to illness or that they multiplied. An examination of the predictions of our best-fit Cox model (Figure 1) clearly shows support for the multiplicative model. In particular, as predicted by this model, neuroticism appears to influence risk for depressive illness in two distinct ways. First, at every level of stress exposure, it directly increases risk of illness. Second, neuroticism moderates the pathogenic effects of stress exposure. Individuals with low levels of neuroticism are much less sensitive to the depressogenic effects of adversity than are those with high levels of neuroticism. These results were verified in our additive model, where we detected highly significant positive interactions between neuroticism and long-term contextual threat in the prediction of risk of depressive onset.

These results are consistent with findings from several previous lines of research. The most comparable prior study, examining 83 elderly depressed patients and 83 matched community comparison subjects (30), showed that stressful life events predisposed to major depression only in those who had high levels of neuroticism or had a prior long-term difficulty. Of four prior studies that examined the interrelationship of neuroticism and various measures of “life stress” in the effect on self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, or distress (31–34), all showed that subjects with high neuroticism levels were more sensitive than subjects with low neuroticism levels to the adverse effects of “stress.”

Brown and Harris (16) suggested an interactive effect of severe stressful life events and certain vulnerability factors (e.g., lack of a confidant, premature loss of parent) in the etiology of major depression. In a subset of our data, we previously showed that genetic risk factors for major depression moderated an individual’s sensitivity to the depressogenic effects of stressful life events (35).

The interpretation of our model results as additive versus multiplicative cannot be separated from assumptions about an appropriate scale of measurement. Much prior discussion has explored whether the appropriate model for biomedical research assumes a scale of raw probabilities or some logarithmic transformation of that scale (as implemented in Cox models or logistic regression) (36–38). While logarithmic transformations certainly provide greater statistical convenience, we favor the position of Rothman (38) that causal assumptions about the independence of the effects of multiple risk factors can be best evaluated with scales of true probabilities. We are particularly impressed by the “public health argument” that our goal is to identify individuals who, when exposed to a given environmental agent, have a particularly large absolute increased risk of illness. We found, in the Cox models, that the interaction between neuroticism and adversity was slightly less than multiplicative for those with high neuroticism levels (because of the modest negative interaction between neuroticism and long-term contextual threat ratings of 3 or higher) (Table 1). When these results were graphed (Figure 1), a substantial multiplicative interaction on the scale of raw probability of illness was evident, and this interaction was statistically verified with our additive model.

Initially, we included sex in these models as a covariate, having previously failed in this sample to find an overall difference in the sensitivity of men and women to the depressogenic effects of stressful life events (18). Unexpectedly, we found a robust interaction between sex and long-term contextual threat. In subjects with no exposure to stressful life events or exposure to events with minor threat, our model predicted a risk for major depression in women slightly more than double that found in men. However, the excess risk in women nearly disappeared in those exposed to events with low moderate, high moderate, or severe long-term contextual threat. We are unaware of a precedent for this finding (3), which is therefore in need of replication. These findings suggest that the origins of the sex effect in risk for major depression may lie in the considerably higher risk in women for episodes that are unrelated to the experience of high-threat events.

Implications

In a previous issue of the Journal(4), we presented—using structural equation modeling—a tentative developmental model for the etiology of major depression in women. Neuroticism and recent stressful life events were among the most potent risk factors identified in that model. We noted that a limitation of the model was the assumption of additivity of individual risk factors in their impact on major depression. These analyses suggest that this assumption was incorrect and that a complete etiologic model for major depression will require not only the additive effects of individual risk factors but also multiplicative interactions between some subsets of them.

Interactions are often difficult to detect statistically and may require special research designs and measurement strategies (37, 38). However, it is plausible that the causal pathways to many if not most psychiatric disorders involve such interactions among key risk factors (40).

Limitations

These results should be considered in the context of two potentially significant methodologic limitations. First, these findings were based on twins from one racial and geographical region and might not extrapolate to other groups. Second, our analyses were based on the assumption that when a stressful life event occurred in the same month as the onset of depression, the stressful life event typically preceded the onset of depression. In another interview section, we asked twins with recent depressive onsets what happened to precipitate the episode. We previously examined interviews from 96 twins who reported both a severe stressful life event and a depressive onset in the same month (35). In 84% of them, the twin reported the same severe stressful life event in the interview section assessing life events and in the section assessing precipitants of the depressive episode. In another 11%, the twin reported a different stressful experience that had co-occurred in the same month, in an understandable sequence that included the event that had been previously reported as co-occurring with the depressive episode. We replicated these results for a later wave (17), and a review of 102 similar cases revealed none in which the depressive onset plausibly preceded the stressful life event. While our data are retrospective (over the recall interval of up to 1 year) and we have no external validation of the reports of stressful life events or depressive onsets, our analyses support the assumption that when both a depressive onset and a stressful life event are reported in the same month, the stressful life event preceded the depression in the vast majority of cases. A modest proportion of the relationship between stressful life events and major depression observed in our data may have resulted from months in which onsets of major depression caused stressful life events.

|

Received Oct. 8, 2002; revisions received Feb. 4 and April 8, 2003; accepted Sept. 5, 2003. From the Virginia Institute for Psychiatry and Behavioral Genetics and the Departments of Psychiatry and Human Genetics, Medical College of Virginia of Virginia Commonwealth University. Address reprint requests to Dr. Kendler, Department of Psychiatry, Medical College of Virginia, P.O. Box 980126, Richmond, VA 23298-0126; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grant MH-40828 from NIMH, by grant MH/AA/DA-49492 from NIMH, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and by grant AA-09095 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry has received support from the National Institutes of Health, the Carman Trust, and the W.M. Keck, John Templeton, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundations. The authors thank the Virginia Twin Registry, now part of the Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry, directed by Dr. L. Corey and L. Eaves, for ascertainment of subjects for this study and Steve Aggen, Ph.D., and Indrani Ray for assistance with database management.

Figure 1. Hazard Ratios Indicating Risk of Onset of Major Depression for a Population-Based Sample (N=7,517) Classified by Sex, Neuroticism, and Stressful Life Eventsa

aA hazard rate of unity was defined as the risk level for a man with a mean score on the 12-item neuroticism scale from the shortened Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (21) and no exposure to stressful life events. Descriptions of the types of stressful life events and the scoring of long-term contextual threat are given in text.

1. Wachs TD, Plomin RE (eds): Conceptualization and Measurement of Organism-Environment Interaction. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1991Google Scholar

2. Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG: Manual of the Eysenck Personality Inventory. London, London University Press, 1964Google Scholar

3. Bebbington P: The origins of sex differences in depressive disorder: bridging the gap. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996; 8:295–332Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA: Toward a comprehensive developmental model for major depression in women. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1133–1145Link, Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC: The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu Rev Psychol 1997; 48:191–214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. John OP: The “big five” factor taxonomy: dimensions of personality in the natural language and in questionnaires, in Handbook of Personality Theory and Research. Edited by Pervin L. New York, Guilford, 1990, pp 66–100Google Scholar

7. Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: A longitudinal twin study of personality and major depression in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:853–862Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. McCrae RR, Costa PT Jr: Personality in Adulthood. New York, Guilford, 1990Google Scholar

9. Hirschfeld RMA, Klerman GL: Personality attributes and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1979; 136:67–70Link, Google Scholar

10. Kendell RE, DiScipio WJ: Eysenck Personality Inventory scores of patients with depressive illnesses. Br J Psychiatry 1968; 114:767–770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wetzel RD, Cloninger CR, Hong B, Reich T: Personality as a subclinical expression of the affective disorders. Compr Psychiatry 1980; 21:197–205Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Angst J, Clayton P: Premorbid personality of depressive, bipolar, and schizophrenic patients with special reference to suicidal issues. Compr Psychiatry 1986; 27:511–532Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hirschfeld RMA, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Keller MB, Griffith P, Coryell W: Premorbid personality assessments of first onset of major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:345–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Fanous A, Gardner CO, Prescott CA, Cancro R, Kendler KS: Neuroticism, major depression and gender: a population-based twin study. Psychol Med 2002; 32:719–728Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA: Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:837–841Link, Google Scholar

16. Brown GW, Harris TO: Social Origins of Depression: A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. London, Tavistock, 1978Google Scholar

17. Kendler KS, Karkowski L, Prescott CA: Stressful life events and major depression: risk period, long-term contextual threat and diagnostic specificity. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186:661–669Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Kendler KS, Thornton LM, Prescott CA: Gender differences in the rates of exposure to stressful life events and sensitivity to their depressogenic effects. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:587–593Link, Google Scholar

19. Kendler KS, Prescott CA: A population-based twin study of lifetime major depression in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:39–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Cohen J: A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychol Measurement 1960; 20:37–46Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ, Barrett P: A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Pers Individ Dif 1985; 6:21–29Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Brown GW: Life events and measurement, in Life Events and Illness. Edited by Brown GW, Harris TO. New York, Guilford, 1989, pp 3–45Google Scholar

23. Fleiss JS, Cohen J, Everett BS: Large sample standard errors of kappa and weighted kappa. Psychol Bull 1969; 72:323–327Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1995Google Scholar

25. Cox DR: Regression models and life tables. J R Statistical Society 1972; 34(Series B):187–220Google Scholar

26. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1999, pp 308–317Google Scholar

27. Masters T: Practical Neural Network Recipes in C++. Boston, Academic Press, 1993Google Scholar

28. Ihaka R, Gentleman R: R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J Computational and Graphical Statistics 1996; 5:299–314Google Scholar

29. Aalen OO: Linear regression model for the analysis of life times. Stat Med 1989; 12:1509–1588Google Scholar

30. Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ, Brilman EI: The interplay and etiological continuity of neuroticism, difficulties, and life events in the etiology of major and subsyndromal, first and recurrent depressive episodes in later life. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:885–891Link, Google Scholar

31. Bolger N, Schilling EA: Personality and the problems of everyday life: the role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. J Pers 1991; 59:355–386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Ormel J, Wohlfarth T: How neuroticism, long-term difficulties, and life situation change influence psychological distress: a longitudinal model. J Pers Soc Psychiatry 1991; 60:744–755Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Rijsdijk FV, Sham PC, Sterne A, Purcell S, McGuffin P, Farmer A, Goldberg D, Mann A, Cherny SS, Webster M, Ball D, Eley TC, Plomin R: Life events and depression in a community sample of siblings. Psychol Med 2001; 31:401–410Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Van Os J, Jones PB: Early risk factors and adult person-environment relationships in affective disorder. Psychol Med 1999; 29:1055–1067Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Kendler KS, Kessler RC, Walters EE, MacLean C, Neale MC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: Stressful life events, genetic liability, and onset of an episode of major depression in women. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:833–842Link, Google Scholar

36. Everitt BS, Smith AMR: Interactions in contingency tables: a brief discussion of alternative definitions. Psychol Med 1979; 9:581–583Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. McCall RB: So many interactions, so little evidence. Why? in Conceptualization and Measurement of Organism-Environment Interaction. Edited by Wachs TD, Plomin RE. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1991Google Scholar

38. Rothman KJ: Modern Epidemiology. Boston, Little, Brown, 1986Google Scholar

39. Wahlsten D: Insensitivity of the analysis of variance to heredity-environment interaction. Behav Brain Sci 1990; 13:109–161Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Wachs TD: Necessary But Not Sufficient. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2000Google Scholar